Search results for "2010/02/2011/04/2009/10/writing-and-power"

A day in the life

30 September 1996 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Drakarna över Helsingfors (‘Kites over Helsingfors’, Söderströms, 1996). Introduction by Jyrki Kiiskinen

It is December 1970, it is Friday afternoon and Helsingfors is shrouded in a damp, leaden-grey fog when Jacke Pettersson, trainee electrician at Mid-Nyland Vocational College, signs a receipt for his driving licence at Vallgård Police Station.

At home in the flat in Svenska Gården in Munkshöjden: the very next evening Jacke sneaks his hand down into his father’s, typesetter K-G. Pettersson’s, overcoat pocket. It is getting on for 9 o’clock and KG is sitting deeply submerged in his favourite armchair, staring concentratedly at the premiere of a new show.

Six out of forty

make it every week

sings a bright girl’s voice.

Then: the Official Supervisors and their solemn ‘Good evening’. And then: the blonde girl in her mini-dress and high boots, the glass holder with its plastic balls, the plastic balls with numbers on. More…

Marjatta Levanto & Julia Vuori: Leonardo. Oikealta vasemmalle [Leonardo. From right to left]

6 March 2015 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Leonardo. Oikealta vasemmalle

Leonardo. Oikealta vasemmalle

[Leonardo. From right to left]

Teksti [Text by]: Marjatta Levanto

Kuvitus [Ill. by]: Julia Vuori

Design: Dog Design

Helsinki: Teos, 2014. 113 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-951851-467-4

€34.90, hardback

This handsome non-fiction book is a lavishly illustrated biography of the 15th-century Italian artist genius Leonardo da Vinci. The title refers to the fact that he employed ‘mirror’ writing in his diaries and notebooks. Art historian Marjatta Levanto has published several works on art for children and young people, and many of them have been illustrated by Julia Vuori. Leonardo introduces to the reader the world of the Italian renaissance, the artist’s astonishing and unique inventions – such as various human flying devices – his philosophical writings, his anatomical studies and his magnificent paintings and drawings. Julia Vuori’s amusing little vignettes and larger, colourful illustrations comment on the narrative and mingle with the text and the reproductions of Leonardo’s artwork. Some pictures are printed on transparent pages. This beautiful book is a treasure trove to a reader of any age.

Dead calm

31 December 2007 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel En lycklig liten ö (‘A happy little island’, Söderströms, 2007)

In the beginning the computer screen was without form, and void, and the scribe’s fingers rested on the keyboard.

The scribe bit his lower lip. His gaze travelled like a fly from the workroom’s crowded bookshelves to the rocking chair in front of the window and the coloured prints of birds on the walls. He went out into the kitchen and drank some water. Then he sat down in front of the computer again.

To create from nothing a fictitious world assisted only by the tools language places at our disposal, surely that must be a great and exacting undertaking!

The scribe hesitated and racked his brains for a long time before finally typing the first word: ‘sky’. Then after long thought he typed another word: ‘sea’. More…

Howl came upon Mr Boo

31 December 1983 | Archives online, Children's books, Drama, Fiction

The first Mr Boo book was published in 1973. Mr Boo has also made his appearance on stage this year; his theatrical companions are the children Mike and Jenny, who are not easily frightened – Mr Boo’s courage is a different matter, as can be seen in the extract from the stage play that follows overleaf.

Hannu Mäkelä describes the birth of Mr Boo:

To be honest, Mr Boo has long been my other self. The first time I drew a character who looked like him, without naming it Boo, I was really thinking of my fifteen year-old self.

The years went by and the Mr Boo drawing was forgotten for a time. It hadn’t occurred to me to write for children; I seemed to have enough to do coping with myself. Then I met Mr Boo, whom I had not yet linked up with my old drawing. My son was about six years old and we had been invited out. There were several children present. As I recall it it was a wet Sunday afternoon. I had entrenched myself with the other grown-ups in the kitchen to drink beer. The noise of the children grew worse and worse (in other words they were enjoying themselves). At last the women could bear it no longer and demanded that I, too, get to work. Really, what right had I always to be sprawled at a table with a beer glass in my hand? None. So I rose and went into the sitting-room. I shouted at the children to form a circle around me. At that time I had a motto: ‘Mäkelä – friend to children and dogs’. The reverse was true of course. The name Mr Boo occurred to me, probably as a result of some obscure private (and possibly even erotic) pun and I begun to tell a story about him. In telling it I paused dramatically and accelerated just as primary school teachers are taught to do: that part of my training, after all, wasn’t wasted. I was astonished; the children listened in complete silence. And if my memory doesn’t fail me (or even if it does, this is the way I wish to remember it), at the end of the story the smallest of the children said, rolling his r’s awkwardly, ‘Hurrrrah’. I was hooked.

The children themselves asked me to tell the same stories again. They still enjoyed them. It wasn’t long before I began to think seriously of writing a whole book about Mr Boo. For the first time in my life I really wanted to write for children. Every day after work I wrote a new Mr Boo story. Then in the evening I read it to my son. That is how the stories grew into a book.

The child likes right to triumph; he likes the good and the moral. The child is the kind of person we adults try in vain to be. It was only through Mr Boo that I began to see children in a totally new way and above all to become seriously interested in them.

Human Freedom

30 June 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Mika Waltari. Photo: SKS Archives

Extract from lhmisen vapaus (‘Human Freedom’, 1950)

‘Where are we?’ Yvonne asked. ‘This isn’t the right street either. Somewhere between Alma and Georges V, they said. But there’s no sign of an aquarium.’

‘Talking of aquariums’, I suggested, ‘there’s a dog shop near here where they wash dogs in the back room. If you like, I’ll take you to see how they wash a dog. It’s a very soothing experience.’

‘You’re crazy’, said Yvonne.

My feelings were hurt. ‘I may sleep badly’, I admitted, ‘but I love you. I walk up and down the embankments all night. My heart aches, my brain is on fire. Then comes blissful intoxication, and for a little while I can be happy. And all you can do is to keep nagging, Gertrude.’

She wrinkled her brow, but I went on impatiently, ‘Look, Rose dear, just at present I have the whole world throbbing in my temples and in my finger-tips. Age-old poems are bubbling up within me. I am grieving for lost youth. I am boggling at the future. For just this one moment it is given to me to see life with the living eyes of a real human being. Why won’t you let me be happy?’

‘I have walked two hundred kilometres’, said a low, timid voice at my elbow. I stopped. Yvonne had stuck her arm through mine. She, too, stopped. We both looked down and saw a little man. He doffed a ragged cap and bowed. Flushed scars glowed through a grey stubble of beard. He was wearing a much-patched battle-dress from which the badges had long since disappeared. His face was wrinkled, but the little eyes were animated and sorrowful. More…

Little and large

5 November 2010 | This 'n' that

A Finnish tale set in Egypt: Mika Waltari's post-war novel has been translated into 30 languages, English in 1949

a about after again against all also always an and another any are around as at away back be because been before being between both but by came can children come could course day did didn’t do does don’t down each end er even every fact far few find first for from get go going good got great had has have he her here him his home house how i i’m if in into is it its it’s just kind know last left life like little long look looked made make man many may me mean me might more most mr much must my never new no not nothing now of off oh old on once one only or other our out over own part people perhaps place put quite rather really right said same say says see she should so some something sort still such take than that that’s the their them there these they thing things think this those though thought three through time to too two under up us used very want was way we well went were what when where which while who why will with without work world would year years yes you your

Doesn’t this just run like a poem? An extract from somebody’s stream of conscience? ‘…again against all also always… quite rather really right said’? Actually it’s a list of the 200 most used words of the English language in alphabetical order.

This remarkable list is among the references* in a new doctoral thesis from the Department of Modern Languages at the University of Helsinki, Englanniksiko maailmanmaineeseen? Suomalaisen proosakaunokirjallisuuden kääntäminen englanniksi Isossa-Britanniassa vuosina 1945–2003 (‘To world fame in English? The translating of Finnish prose fiction into English in Great Britain between 1945 and 2003’). More…

On the rocky road to a good translation

19 November 2010 | Essays, Non-fiction

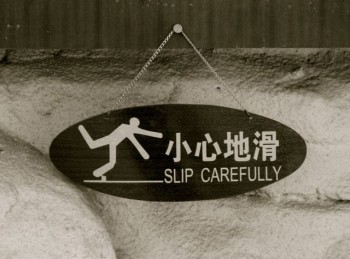

You get the picture? A translation error in China. Photo: Leena Lahti

Why just three per cent? Translator Owen Witesman seeks an explanation for the difficulties of selling foreign fiction to the self-sufficient Anglo-American market. Could there be anything wrong with the translations?

I am a professional translator, and I have a secret: I don’t read translations.

I’m not alone. The literary website Three Percent draws its name from the fact that only about 3 per cent of books published in the United States are translations (the figure for Germany is something like 50 per cent). There are various opinions about why this is, including this one from Three Percent’s Chad Post writing at Publishing Perspectives.

Why do I say it’s a secret that I don’t read translations? Because people expect me to read translations, as if as a translator it were my sacred duty to show solidarity with my professional community. Or maybe I can’t be cosmopolitan otherwise. More…

Fiat lux! Helsinki lit

9 January 2014 | This 'n' that

When there’s no snow in January, as is the case this year, the darkness does make Helsinki appear somewhat joyless. This year Canada and parts of the United States got more than a taste of freezing Arctic temperatures – but at the time of writing winter is still postponed in the lower half of Finland.

When there’s no snow in January, as is the case this year, the darkness does make Helsinki appear somewhat joyless. This year Canada and parts of the United States got more than a taste of freezing Arctic temperatures – but at the time of writing winter is still postponed in the lower half of Finland.

A temporary relief was brought by Lux Helsinki – staged now for the sixth time – as light, colour and sound made the capital brighter and more beautiful between 4 and 8 January.

The core of the city, the Cathedral, was adorned by a large heart placed at the top of the steps, beating in colours to music.

Corazón by Agatha Ruiz de la Prada. Photo: Marina Okras

Corazón, by the Madrid-born artist and fashion designer Agatha Ruiz de la Prada, in collaboration with the production and design company D-Facto, reflects her design themes of love and happiness.

One of the participants in Lux Helsinki was Unen ääret / Edges of Dreams: projected on to the façade of the Hakasalmi Villa (1843–46), between the Finlandia Hall and the Music House, it was inspired by the history of the building and its inhabitants. Now a museum, it became known as the home of a benefactor of the city, a rich and famous woman of her time, Aurora Karamzin from the 1860s to the 1890s.

Hakasalmi Villa: Edges of Dreams by Mika Haaranen. Photo: Lauri Rotko

The building was seen through dreamlike visions formed by painted films and shadow patterns by Mika Haaranen, a lighting and set designer and photographer. His works extend from the world of theatre and musicals to contemporary dance, concerts and film. The accompanying music was composed by Aake Otsala.

Lux Tram by students of lighting and sound design, Theatre Academy. Photo: Hannu Iso-Oja

Helsinki trams have been transporting citizens from 1891. One of the trams was transformed into a moving light installation by the use of programmable LED floodlights. The work was designed and realised by the Theatre Academy of the University of the Arts Helsinki lighting design students Riikka Karjalainen and Alexander Salvesen. A pity it was not possible to hop on…

A greater solitude

30 December 2004 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Runoilijan talossa (‘In the house of the poet’, Tammi, 2004)

Images of love

The double door to the patio is tightly swollen into the framework, so tight I’m chary of using force to prize it open. The windows might break. The lower part remains stuck, as if screwed to a carpenter’s bench, while the upper part gapes – leans out as if longing to liberate itself from its lintel. That’s an image of love: one part longs to be free, the other part holds on fast. I get a toolbox from the cleaning cupboard and try to hammer a chisel into the space between the bottom edge and the threshold. I succeed, but the chisel marks the door, defacing it. That’s an image of love too. More…

And the winner is…?

27 March 2012 | This 'n' that

Playing your cards right: Todd Zuniga talks to Riikka Pulkkinen on 20 March in Helsinki. Photo: courtesy/T. Zuniga

The writer Johanna Sinisalo’s words lash the stage like the tail of Pessi the troll in her best-known novel. The novelist Riikka Pulkkinen bursts into deconstructive dance. The singer Anni Mattila translates the poet Teemu Manninen’s explosive poetic frolics into rhythmic dictations and the Finlandia Prize-winning author Rosa Liksom’s conductor’s glittering moustaches see the audience off on a train journey to Moscow.

On a March evening, a Literary Death Match has begun in the Korjaamo Culture Factory in Helsinki’s old tramsheds. The creation of the American author and journalist Todd Zuniga, the Literary Death Match combines an evening of readings with stand-up comedy as well as the judging familiar from reality TV shows.

‘It all started with me eating sushi with two of my friends and talking about some of the readings we’d been to. We all loved literature and loved to listen to writers reading from their own work. But the audience was always the same circle of people. We wanted to expand it beyond literary circles,’ Zuniga explains. More…

Leena Kirstinä on the iconoclastic and pioneering poet – for children and adults –

Leena Kirstinä on the iconoclastic and pioneering poet – for children and adults –