Search results for "2010/02/2011/04/2009/10/writing-and-power"

Secret lives

30 September 2002 | Fiction, Prose

From Piiloutujan maa (‘The land of the hider’, Otava, 2002)

When we look for a good apartment, a good café, a good place to be, we are looking for a childhood hideaway. We are looking for the wardrobe we used to retreat into when we had been hurt. We will always remember what being there feels like. We yearn for that same illumination, felt by the baby Jesus in Mary’s womb, as the world’s light shone in through the hymen. More…

Breathe out, breathe in

30 June 1999 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Nio dagar utan namn (‘Nine days without names’, Söderströms, 1998). Introduction by Bror Rönnholm

Quickly, at a zebra crossing

moments

not of wonder but of something closely related: the tree

upturned by the gale with its roots to the heavens, the lit-up

church spire against the night sky, a few simple gravestones viewed at a

suitable season, a quartet from the Marriage of Figaro or just standing at a roaring

crossing and writing this, invisible to all in exhaust fumes and a faint blue

light from a hidden sun, a few times mistaken for a

loved pupil More...

New from the archive

26 March 2015 | This 'n' that

This week, a cluster of pieces from and about left-leaning Tampere, the ‘Red City’ of Finland

The Tampella and Finlayson factories, 1954, Tampere. Photo: Veikko Kanninen, Vapriikki Photo Archives / CC BY-SA 2.0.

Also known as the ‘Manchester of Finland’ for its 19th-century manufacturing tradition, Tampere – or rather the suburb of Pispala – produced two important, and strongly contrasting, writers, Lauri Viita (1916-1965) and Hannu Salama (born 1936). Both formed part of a group of working-class writers who emerged after the Second World War, many of whom had not completed their school careers and whose confidence arose from independent, auto-didactic, reading and study.

To understand the place from which these writers emerged, it has to be remembered that there is more to Tampere than a proud radical tradition. As Pekka Tarkka remembers in his essay, the Reds were the losing side in the Finnish civil war of 1918, and for years afterwards they formed ‘a sort of embattled camp in Finnish society’. History is always written by the winners, and authors like Viita and Salama played an important role in giving the Red side back its voice.

Lauri Viita.

Lauri Viita celebrated Tampere by offering an image of it that is, as Tarkka remarks, ‘poetic, deterministic and materialist’. His poetry differed sharply from the modernist verse of contemporaries such as Paavo Haavikko and Eeva-Liisa Manner, both of whom we have featured recently in our Archive pieces, which abandoned both fixed metres and end-rhymes. His work was an often heroic celebration of the ordinary life of proletarian Tampere, and the more traditional form into which it breathed new life made it accessible. My own mother, for example, who had grown up the child of a Red working-class family far away to the north, in Kajaani, steeped in the rolling cadences of poets such as Aaro Hellaakoski and Uuno Kailas, never really got the hang of Haavikko, or Manner; but she loved Viita.

Here we publish a selection of Viita’s poems, translated by Herbert Lomas, who does an excellent job of capturing his easy-going, unselfconscious rhythms. The introduction is by Kai Laitinen.

Hannu Salama.

Photo: Ptoukkar / CC BY-SA 3.0

Salama is a far more politicised writer than Viita, and he is writing about a Tampere that is already in decline. In his major work, Siinä näkijä missä tekijä (‘No crime without a witness’, 1972), he writes about the travails of the communist minority, doomed to slow extinction – the same band of fellow-travellers to which my grandfather in Kajaani belonged. My mother wasn’t a Salama fan, though – I think his Tampere wasn’t beautiful, or heroic, enough. As someone who had moved far away, to England, she wanted to celebrate, not to mourn.

Here we publish a short story, Hautajaiset (‘The funeral’), which was written at the same time as Siinä näkijä missä tekijä. It’s an unvarnished account of a Tampere funeral which is, at the same time, the funeral of the old, radical way of life – which, sure enough, has vanished almost as if it never existed. As Pekka Tarkka writes of Salama’s short story and the revolutionary songs which run through it: ‘There will be no more singing of communist psalms, or fantasies of the family and of the revolutionary spirit.’

As Marx didn’t say, all that seemed so solid has melted, irretrievably, into air.

*

The digitisation of Books from Finland continues, with a total of 380 articles and book extracts made available online so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

New from the archives

11 May 2015 | This 'n' that

Juhani Peltonen. Photo: C-G Hagström / WSOY.

This week’s pick is, like last week’s, a period piece – this time a cry for help from the 1980s in the work of Juhani Peltonen (1941-1998).

Like Runar Schildt’s short story Raketen, written shortly before Finland gained independence from Russia and was almost immediately plunged into civil war, these pieces by the multitalented Juhani Peltonen, who wrote plays for stage and radio as well as short stories, novels and poems, were published shortly before major and irrevocable change.

In the short story ‘The Blinking Doll’, we are a year short of the fall of the Berlin Wall, and it seems as if things are never going to change. We follow two forty-year-old lawyers, Juutinen and Multikka, as they trudge along the beach in one of the charming resort towns of the west coast in which they have spent a couple of days dealing with a minor felony case.

They’re both forty, and divorced, disillusioned with their jobs and with the world; and both are infatuated with one of their colleagues, a woman whom they call ‘The Blinking Doll’.

There is, Peltonen says, a ‘pact of friendship and mutual assistance between the men’ – a jocular reference to the notorious treaty of 1948 in which Finland was obliged to resist attacks on the Soviet Union through its territory, and to ask for Soviet aid if necessary. In 1988, this seemed as if it were written in stone – and the men’s emotional lives are similarly petrified. They discuss their isolation, their lack of purpose, their inexplicable weeping fits. The most painful thing, says Multikka, is love; or, says Juutinen, and which comes to the same thing, the lack of it.

As Erkka Lehtola, our then Editor-in-Chief, remarks in his introduction, Peltonen – Finnish literature’s best-known comi-tragedian, he calls him – focuses on the difficulty of loving in a violent, mechanical, oppressed world. Is it the passage of twenty-five years that imbues his writing with such a poignant sense of stasis and futility? There is a sense of desperation, barely controlled. As one of his poems has it,

Too abundant in the course of the evening

Cries for help from the heart of stifled detail, legato.

![]()

The Books from Finland digitisation project continues, with a total of 388 articles and book extracts made available on our website so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

It’s four o’clock and the dog is puzzled

26 September 2013 | This 'n' that

Cover image: ‘Autumn reflections’ by author and painter Saara Tikka

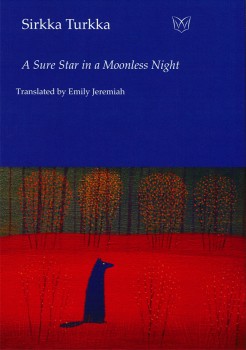

Apart from writing poetry for forty years, Sirkka Turkka has worked as a stable master and as a librarian – and she is a wizard in creating portraits of dogs in her poems.

‘Something kept me awake late. Something woke me up early. It’s four o’clock and the dog is puzzled. He tries to continue his dream: he was just about to catch a squirrel he barked at all of yesterday. He leaves me quite alone in silence, in which not a single breeze stirs. What is in the past ceases to be, what is to come has no significance. There is only the sun, just about to come up. And the calm surface of the lake and the coffee cup, from which leisurely steam rises.’ (From Minä se olen [‘It’s me’], 1973)

Elk, horse, raven, reindeer, jackdaw, fox. Turkka’s universe is populated with creatures, often wiser than man: man may have lost his heart, or ‘he thinks it’s a distant land’, but ‘in dogs the heart is where it should be: just after the muzzle, boulder-like, baby-faced and willing.’ (From Yö aukeaa kuin vilja [‘The night opens like corn’], 1978).

Emily Jeremiah, scholar and translator (her work includes poems by Eeva-Liisa Manner, novels by Asko Sahlberg and Kristina Carlson), found Turkka’s creatures a while ago, and as a result a selection of Turkka’s poems, entitled A Sure Star in a Moonless Night, was published recently by Waterloo Press (UK).

Melancholy: it does go well with autumn, doesn’t it? ‘Once more the stars are like a tearful ballad, and always in the evenings / the dogs tune their cracked violins.’ (From Mies joka rakasti vaimoaan liikaa [‘The man who loved his wife too much’, 1979])

Alexandra Salmela: Kirahviäiti ja muita hölmöjä aikuisia [The giraffe mummy and other silly adults]

9 January 2014 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kirahviäiti ja muita hölmöjä aikuisia

Kirahviäiti ja muita hölmöjä aikuisia

[The giraffe mummy and other silly adults]

Kuvitus [Ill. by]: Martina Matlovicová

Helsinki: Teos, 2013. 96 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-951-851-466-7

€27.90, hardback

The first children’s book by Alexandra Salmela, who has previously published a novel for adults, brings some sorely needed anarchy to Finnish storybooks. The 21 brief stories encourage children to add to them, whether by drawing, writing or out loud. Salmela’s tales are populated by trolls, dragons, knights and princesses, as well as ordinary children with silly parents. A boy called Ossi has two mums: Little Mum and Big Mum. One night, Little Mum collapses under the Tree of Exhaustion, but Ossi and his little sister hug their mum better. Allu’s absent-minded dad manages to mislay his head, and two perfect parents trade in their defective son Sulo at the child repair shop. The collage images by Slovakian illustrator Martina Matlovičová will work their way straight into your subconscious and start to bubble away.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

Burnt orange

30 September 1992 | Archives online, Drama, Fiction

Extracts from the play Poltettu oranssi (‘Burnt orange‘): ‘a ballad in three acts concerning the snares of the world and the blood’. Introduction by Tuula Hökkä

The scene is a small town in the decade before the First World War

Cast:

DR FROMM

an imperial,bearded middle-aged gentleman

ERNEST KLEIN

a moustached, ageing, slightly shabby leather-manufacturer

AMANDA KLEIN

his wife, well-preserved, forceful, angular

MARINA KLEIN

their daughter, shapely, withdrawn, wary

NURSE-RECEPTIONIST

open, direct, not too ‘common’

ACT ONE

Scene two

After a short interval the receptionist opens the door and ushers Marina Klein into the surgery. Exit the receptionist. Marina immediately goes to the end of the room and presses herself against the white wall. The white surface makes her look very isolated in her ascetic black dress. The Doctor, who now appears to be headless – an impression produced by the lighting and the yellowish background – half-turns towards her. More…

Digital dreams

4 February 2009 | Essays, Non-fiction

In this specially commissioned article, the first for the new Books from Finland website, Leena Krohn contemplates the internet and the invisible limits of literature.

Leena Krohn on the way to Cape Tainaron, Southern Peloponnese, Greece; this is where Europe ends. Her novel entitled Tainaron appeared in 1985. – Photo: Mikael Böök (2008)

The world wide web, whose services most of us now use for work or entertainment, is a greater invention than we have, perhaps, realised up till now: according to the writer Leena Krohn, it is nothing less than an evolutionary leap

Technology combats the limitations of our senses, geography, and time. The human eye can’t compete with the visual acuity of an eagle, or even a cat, but with the best telescopes it can see into the early history of the universe, with new electron microscopes it can distinguish individual atoms.

The human senses nevertheless have an unbelievably broad bandwidth. About a million times more data flows to our brains by means of our senses than we could ever grasp consciously. More…

How much did Finland read?

30 January 2014 | In the news

The book year 2013 showed an overall decrease – again: now for the fifth time – in book sales: 2.3 per cent less than in 2012. Fiction for adults and children as well as non-fiction sold 3–5 per cent less, whereas textbooks sold 4 per cent more, as did paperbacks, 2 per cent. The results were published by the Finnish Book Publishers’ Association on 28 January.

The book year 2013 showed an overall decrease – again: now for the fifth time – in book sales: 2.3 per cent less than in 2012. Fiction for adults and children as well as non-fiction sold 3–5 per cent less, whereas textbooks sold 4 per cent more, as did paperbacks, 2 per cent. The results were published by the Finnish Book Publishers’ Association on 28 January.

The overall best-seller on the Finnish fiction list in 2013 was Me, Keisarinna (‘We, tsarina’, Otava), a novel about Catherine the Great by Laila Hirvisaari. Hirvisaari is a queen of editions with her historical novels mainly focusing on women’s lives and Karelia: her 40 novels have sold four million copies.

However, her latest book sold less well than usual, with 62,800 copies. This was much less than the two best-selling novels of 2012: both the Finlandia Prize winner, Is, Jää (‘Ice’) by Ulla-Lena Lundberg, and the latest book by Sofi Oksanen, Kun kyyhkyset katosivat (‘When the doves disappeared’), sold more than 100,000 copies.

The winner of the 2013 Finlandia Prize for Fiction, Riikka Pelo’s Jokapäiväinen elämämme (‘Our everyday life’, Teos) sold 45,300 copies and was at fourth place on the list. Pauliina Rauhala’s first novel, Taivaslaulu (‘Heaven song’, Gummerus), about the problems of a young couple within a religious revivalist movement that bans family planning was, slightly surprisingly, number nine with almost 30,000 copies.

The best-selling translated fiction list was – not surprisingly – dominated by crime literature: number one was Dan Brown’s Inferno, with 60,400 copies.

Number one on the non-fiction list was, also not surprisingly, Guinness World Records with 35,700 copies. Next came a biography of Nokia man Jorma Ollila. The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction, Murtuneet mielet (‘Broken minds’, WSOY), sold 22,600 copies and was number seven on the list.

Eight books by the illustrator and comics writer Mauri Kunnas featured on the list of best-selling books for children and young people, with 105,000 copies sold. At 19th place was an Angry Birds book by Rovio Enterntainment. The winner of the Finlandia Junior Prize, Poika joka menetti muistinsa (‘The boy who lost his memory’, Otava), was at fifth place.

Kunnas was also number one on the Finnish comic books list – with his version of a 1960s rock band suspiciously reminiscent of the Rolling Stones – which added 12,400 copies to the figure of 105,000.

The best-selling e-book turned was a Fingerpori series comic book by Pertti Jarla: 13,700 copies. The sales of e-books are still very modest in Finland, despite the fact that the number of ten best-selling e-books, 87,000, grew from 2012 by 35,000 copies.

The cold fact is that Finns are buying fewer printed books. What can be done? Writing and publishing better and/or more interesting books and selling them more efficiently? Or is this just something we will have to accept in an era when books will have less and less significance in our lives?

Kynällä kyntäjät. Kansan kirjallistuminen 1800-luvun Suomessa [Ploughers with a pen. The development of literacy in nineteenth-century Finland]

15 May 2014 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kynällä kyntäjät. Kansan kirjallistuminen 1800-luvun Suomessa

Kynällä kyntäjät. Kansan kirjallistuminen 1800-luvun Suomessa

[Ploughers with a pen. The development of literacy in nineteenth-century Finland]

Toimittajat [Editors]: Lea Laitinen & Kati Mikkola

Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2013. 558 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-453-8

€42, paperback

This multidisciplinary work by thirteen researchers discusses the writings of self-taught people in the 19th century. In their own communities these Finnish-language amateur authors were exceptions to the norm, but viewed in the context of the Finnish nation as a whole there were more of them than there were authors belonging to the educated classes. The principal aim is to examine how the common people saw the social and cultural phenomena which the educated classes saw from their own perspective. Kynällä kyntäjät provides a background to the research of the subject and the spread of writing ability, presenting diaries, biographies, letters, rural poetry published in newspapers, broadside ballads, plays, short stories, collections of folklore and handwritten journals, as well as focusing on the mental and linguistic changes related to the development of literacy. The book opens up a new and fascinating perspective on the 19th-century world of ideas.

Translated by David McDuff