Search results for "2010/02/let-us-eat-cake"

Let us eat cake

4 February 2010 | This 'n' that

Here at Books from Finland central we’re celebrating, with the one Finnish literary anniversary that involves its own dedicated cake.

The fifth of February marks the birthday of the poet J.L. Runeberg (1804–1877) – writer, among many other things, of the Finnish national anthem (actually unofficial, as there’s no mention of such a thing in the legislation), which he wrote in Swedish, Vårt land (in Finnish, Maamme). More…

3 x Runeberg: poet, cake & prize

5 February 2014 | This 'n' that

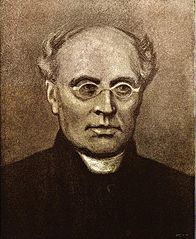

J.L. Runeberg. Painting by Albert Edelfelt, 1893. WIkipedia

Today, the fifth of February, marks the birthday of the poet J.L. Runeberg (1804–1877), writer, among other things, of the words of Finnish national anthem.

Runeberg’s birthday is celebrated among the literary community by the award of the Runeberg Prize for fiction; the winner is announced in Runeberg’s house, in the town of Borgå/Porvoo.

Runeberg’s favourite. Photo: Ville Koistinen

Mrs Runeberg, a mother of seven and also a writer, is said to have baked ‘Runeberg’s cakes’ for her husband, and these cakes are still sold on 5 February. Read more – and even find a recipe for them – by clicking our story Let us eat cake!

The Runeberg Prize 2014, worth €10,000, went to Hannu Raittila and his novel Terminaali (‘Terminal’, Siltala).

Hannu Raittila. Photo: Laura Malmivaara

According to the members of the prize jury – the literary scholar Rita Paqvalen, the author Sari Peltoniemi and the critic and writer Merja Leppälahti – they were unanimous in their decision; however, the winner of the 2013 Finlandia Prize for Fiction, Jokapäiväinen elämämme (‘Our everyday lives’) by Riikka Pelo, was also seriously considered.

Read more about the 2014 Runeberg shortlist In the news.

The way to heaven

30 June 1996 | Archives online, Fiction

Extracts from the novel Pyhiesi yhteyteen (‘Numbered among your saints’, WSOY, 1995). Interview with Jari Tervo by Jari Tervo

The wind sighs. The sound comes about when a cloud drives through a tree. I hear birds, as a young girl I could identify the species from the song; now I can no longer see them properly, and hear only distant song. Whether sparrow, titmouse or lark. Exact names, too, tend to disappear. Sometimes, in the old people’s home, I find myself staring at my food, what it is served on, and can’t get the name into my head. The sun came to my grandson’s funeral. It rose from the grave into which my little Marzipan will be lowered. I don’t remember what the weather did when my husband was buried.

A plate. Food is served on a plate. There are deep plates and shallow plates; soups are ladled into the deep ones. More…

Becoming father and daughter

31 December 1990 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A father kidnaps his 10-year-old daughter and flees to the western extremity of Europe, to Ireland, to begin a new life under new names. In the following extract, the girl is in a state of shock after witnessing an event organised by a religious sect in which animals are driven over a cliff to their death. The year 2000 approaches, and with it clarification of the relationship between father and daughter. An extract from Olli Jalonen’s novel Isäksi ja tyttäreksi (‘Becoming father and daughter’). Introduction by Erkka Lehtola

He begins leading his daughter back the way they came, along the hillside and the lip of the precipice.

The blare of the Legion’s display carries far, till finally the voices are scrambled in the bluster of the wind. The electricity crackles in the loudspeakers, and the thundersheets rumble out to the audience. ‘Be silent!’ come the roars from the plat form: ‘And look at each other! Each is fearfully following his way, each is a venue of good and evil, each is inscribed with God’s name!’ More…

Rainer Knapas: Kunskapens rike. Helsingfors universitetsbibliotek – Nationalbiblioteket 1640–2010 [In the kingdom of knowledge. Helsinki University Library – National Library of Finland 1640–2010]

9 August 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kunskapens rike. Helsingfors universitetsbibliotek – Nationalbiblioteket 1640–2010

Kunskapens rike. Helsingfors universitetsbibliotek – Nationalbiblioteket 1640–2010

Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 2012. 462 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-583-244-3

€54, hardback

Tiedon valtakunnassa. Helsingin yliopiston kirjasto – Kansalliskirjasto 1640–2010

[In the kingdom of knowledge. Helsinki University Library – National Library of Finland 1640–2010]

Suomennos [Finnish translation by]: Liisa Suvikumpu

Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2012. 461 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-272-5

€54, hardback

The National Library of Finland was founded in 1640 as the library of Turku Academy. In 1827 it was destroyed by fire: only 828 books were preserved. In 1809 Finland was annexed from Sweden by Russia, and the collection was moved to the new capital of Helsinki, where it formed the basis of the University Library. The neoclassical main building designed by Carl Ludwig Engel is regarded as one of Europe’s most beautiful libraries and was completed in 1845, with an extension added in 1906. Its collections include the Finnish National Bibliography, an internationally respected Slavonic Library, the private Monrepos collection from 18th-century Russia, and the valuable library of maps compiled by the arctic explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld. Renamed in 2006 as Kansalliskirjasto – the National Library of Finland – this institution, which is open to general public, now contains a collection of over three million volumes as well as a host of online services. This beautifully illustrated book by historian and writer Rainer Knapas provides an interesting exposition of the library’s history, the building of its collections and building projects, and also a lively portrait of its talented – and sometimes eccentric – librarians.

Translated by David McDuff

About calendars and other documents

30 June 1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Sudenkorento (‘The dragonfly’, 1970). Introduction by Aarne Kinnunen

I now have. Right here in front of me. To be interviewed. Insulin artist. Caleb Buttocks. I have heard. About his decision. To grasp his nearly. Nonexistent hair and. Lift. Himself and. At the same time. His horse. Out of the swamp into which. He. Claims. He has sunk so deep that. Only. His nose is showing. How is it now, toe dancer Caleb Buttocks. Are you. Perhaps. Or is It your intention. To explain. The self in the world or. The world. In the self. Or is It now that. Just when you. Finally have agreed to. Be interviewed by yourself. You have decided. To go. To the bar for a beer?

– Yes. Can you spare a ten?

– Yes.

– Thanks. See, what’s really happened is that. My hands have started shaking. But when I down two or three bottles of beer, that corpse-washing water as I’ve heard them call it, my hands stop shaking and I don’t make so many typing errors. If I put away six or seven they stop shaking even more and the typing mistakes turn really strange. They become like dreams: all of a sudden you notice you’ve struck it just right. Let’s say, ‘arty’ becomes ‘farty’. Or I mean to say, ‘it strikes me to the core’ I end up typing ‘score’. It’s like that. A friend of mine, an artist, once stuck a revolver in my hand. Imagine, a revolver! I’ve never shot anything with any kind of weapon except a puppy once with a miniature rifle. My God, how nicely it wagged its tail when I aimed at it, but what I’m talking about are handguns, those shiny black steelblue clumps people worship as heaven knows what symbols. It’s not as if I haven’t been hoping to all my life. And now, finally, after I’d waited over fifty years, it turned out that the revolver was a star Nagant, just the kind I’d always dreamed of. So if I ever got one of those, oh, then would sleep through the lulls between shots with that black steel clump ready under my pillow. Well, my friend the artist set out one vodka bottle with a white label and three brown beer bottles with gold labels on the edge of a potato pit – we had just emptied all of them together – stuck the fully loaded star Nagant into my hand, took me thirty yards away and said:

– Oh, Lord. More…

It’s only me

Extracts from the autobiographical novel Pienin yhteinen jaettava (‘Lowest common multiple’, WSOY, 1998)

The weather had not yet broken, although it was September; I had been away for two weeks.

The linden trees of the North Shore drooped their dusty leaves in a tired and melancholy way. Even the new windows were already sticky and dusty. The flat was covered in thick, stiff plastic sheeting. The chairs, the books, the Tibetan tankas and the negro orchestra I had bought in Stockholm glimmered beneath the plastic ice like salvage from the Titanic.

The windows had been replaced while I had been in Korea.

I unpacked the gifts from my suitcase. Lost in the sea of plastic, the little Korean objects looked shipwrecked and ridiculous.

My temperature was rising; it had been troubling me for more than a week.

I smiled and said something, not mentioning my temperature.

It was time to be a mother again, and a life-companion.

And a daughter…. More…

The engineer’s story

30 June 1981 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Maailman kivisin paikka (‘The stoniest place in the world’, 1980). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Coffee was going to be served down by the river. The engineer took my elbow and led me across his paved courtyard and over his lawn; we settled ourselves down in cane chairs under the trees. Mirja came out of the house with a tray of coffee and coffee-cups, a loaf of sweet bread, already cut, some marble cake and some biscuits. The engineer said nothing. My eye wandered over the ample weeping birches by the river, the mist creeping up in the cool of the evening and shifting in the cross-pull of the breeze and the current, and I watched Mirja moving under the trees back to the house and then down again to the riverbank.

As we sipped our coffee we spoke about chance, and the part it plays in life, about my husband – for I was able to speak about him now: enough time had gone by. The engineer eased himself into a comfortable position, gave me a quick look and then launched off into an account of his own, about his trip abroad:

I spotted the news item as I was going through the morning paper on the plane. I sat more or less speechless all of the first leg, listening to Kirsti and her husband confabulating. I didn’t say anything during the stop-over in Copenhagen, either, where they wanted to get some schnapps and, of course, some chocolate ‘if Kirsti would really like some’. We came rushing back into the plane just as the last English, German and Danish announcements were coming over, and then we sat waiting for the take-off. That was delayed too because of a check-up (not announced), and then we were off again for Zurich, me without a word and they whispering together. Then it was the bus as far as the terminal, and after that a taxi to the hotel. Quite clearly Kirsti hadn’t heard a thing about it yet, and probably hadn’t had much contact with Erkki for quite some time, her new husband even less. More…

Living with Her Ladyship

31 December 2003 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the memoir of a Helsinki childhood, Från Twenty Gold till Kent (‘From Twenty Gold to Kent’, Schildts, 2003). Introduction by Pia Ingström

My hair was dark and stuck up from my skull like little nails. My face was furrowed with red, my throat was wrinkled and I didn’t even have a pretty navel. This was because Daddy had to knot my umbilical cord himself while the obstetrician was busy on the ground floor with an appendix.

‘She looks like a forty-year-old errand-boy from the newspaper’s office: Daddy announced.

Mummy said she hoped I would soon change and have a long neck.

At Apollogatan street we took the lift up to the third floor where my sisters were waiting with the new nanny. They had no chance to welcome me with singing as they’d planned because both Renata and Catherine had colds. Nobody was going to be allowed to breathe anywhere near me, Mummy and Nanny were entirely agreed on that. More…

Summer child

30 September 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Resa med lätt bagage (‘Travelling light’, 1987). Introduction by Marianne Bargum

From the very beginning it was quite clear no one at Backen liked him, a thin gloomy child of eleven; he looked hungry somehow. The boy ought to have inspired a natural protective tenderness, but he didn’t at all. To some extent, it was his way of looking at them, or rather of observing them, a suspicious, penetrating look, anything but childish. And when he had finished looking, he commented in his own precocious way, and my goodness, what that child could wring out of himself.

It would have been easier to ignore if Elis had come from a poor home, but he hadn’t. His clothes and suitcase were sheer luxury, and his father’s car had dropped him off at the ferry. It had all been arranged over the phone. The Fredriksons had taken on a summer child out of the goodness of their hearts, and naturally for some compensation. Axel and Hanna had talked about it for a long time, about how town children needed fresh air and trees and water and healthy food. They had said all the usual things, until they had all been convinced that only one thing was left in order to do the right thing and feel at ease. Despite the fact that all the June work was upon them, many of the summer visitors’ boats were still on the slips, and the overhaul of some not even completed. More…

Daddy dear

30 June 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Vanikan palat (‘Pieces of crispbread’, Otava, 2004). Interview by Soila Lehtonen

Dad’s at the mess again. Comes back some time in the early hours. Clattering, blubbing, clinging to some poem, he collapses in the hall.

We pretend to sleep. It’s not a bad idea to take a little nap. After a quarter of an hour Dad wakes up. Comes to drag us from our beds. Crushes us four sobbing boys against his chest as if he were afraid that a creeping foe intended to steal us. We cry too, of course, but from pain. Four boys belted around a non-commissioned officer is too much. It hurts. And the grip only tightens. Dad whines:

‘Boys, I will never leave you. Dad will never give his boys away. There will be no one who can take you from me.’ More…

Animal crackers

30 June 2004 | Children's books, Fiction

Fables from the children’s book Gepardi katsoo peiliin (‘A cheetah looks into the mirror’, Tammi, 2003). Illustrations by Kirsi Neuvonen

Rhinoceros

The rhinoceros was late. She went blundering along a green tunnel she’d thrashed through the jungle. On her way, she plucked a leaf or two between her lips and could herself hear the thundering of her own feet. Snakes’ tails flashed away from the branches and apes bounded out of the rhino’s path, screaming. The rhino had booked an afternoon appointment and the sun had already passed the zenith.

The rhinoceros was late. She went blundering along a green tunnel she’d thrashed through the jungle. On her way, she plucked a leaf or two between her lips and could herself hear the thundering of her own feet. Snakes’ tails flashed away from the branches and apes bounded out of the rhino’s path, screaming. The rhino had booked an afternoon appointment and the sun had already passed the zenith.

When the rhinoceros finally arrived at the beautician’s, the cosmetologist had already prepared her mud bath. The rhino was able to throw herself straight in, and mud went splattering all round the wide hollow. More…

The ladies’ dining club

30 September 1994 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From the novel Luonnollinen ravinto (‘A natural diet’, WSOY, 1994). Interview by Tuva Korsström

My dear, wise and ever-faithful secretary, colleague, friend and right hand, you who, without counting the hours, have been my helpmeet in many awkward situations, and not only in work matters but in others, all sorts of matters that belong to my private life and particularly those, you have remembered things that I have found hard to remember, like the birthday of my wife or some important colleague, and at Christmas you have always remembered me with some small gift, always different and always carefully chosen, of which I hardly need say how much it has warmed my heart, when I haven’t been able to do better than a single miserable hyacinth. And you have always reminded me of engagements I haven’t been able to keep track of: dentists, barbers, garages, less important and more important receptions, lunches and dinners, but what is most important, and why l am most grateful to you, is that in your generosity and open-mindedness – your eternal femininity – you have understood that a person in my position may sometimes find himself in situations whose consequences he cannot always control, and that he begins to be bothered by all sorts of people, although they should understand from the smallest hint that their company is not required, and you have sensitively but firmly turned them away, sometimes telling a little lie, and you have never, ever taken a moral stand or judged my actions, but have averted your eyes, having made the decision to accept that your boss is anything but perfect. For that reason I wish to express my gratitude to you; but not, however, unreservedly. Our seamless collaboration, my ever-lovable secretary, has meant that something belonging to me has begun to belong to you, that you have become part of me just as I have become part of my wife, even before she touches me with her fork. So I have no doubt that you, too, could appear at the dinner that is soon to be arranged. Bon appetit! More…

Cruising

30 September 1993 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Vieras (‘The stranger’, Otava 1992). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

I lay there for a moment, motionless, eyes closed.

The bunk was damp. It felt damp around my thighs; I slid down lower – and there, it was really wet.

My sleeping bag was obviously soaked, and that meant that the mattress was soaked, too. Oh, rats. I couldn’t imagine having wet myself. Or – worse – had the boat sprung a leak, the water already rising up to the floorboards? I bounded to my feet: the rugs were dry. So was the cabin floor. I raised the boards, peered down: two fingers of water in the forward bilge, as usual. So, where the –? In the course of yesterday’s rough sailing, some water had seeped in below the windowframe. No more than a cupful, but it had trickled down inside the panel and then onto the mattress. I tried the other side of the bunk. It was dry. Well, I would just have to pick up the mattress and set it on its side. More…