Search results for "2010/05/2011/04/matti-suurpaa-parnasso-1951–2011-parnasso-1951–2011"

Finland(ia) of the present day

2 December 2010 | In the news

Mikko Rimminen. Photo: Heini Lehväslaiho

The Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2010, worth €30,000, was awarded on 2 December to Mikko Rimminen (born 1975) ; his novel Nenäpäivä (‘Nose day’, Teos) was selected by the cultural journalist and editor Minna Joenniemi from a shortlist of six.

Appointed by the Finnish Book Foundation, the prize jury (Marianne Bargum, former publishing director of Söderströms, researcher and writer Lari Kotilainen and communications consultant Kirsi Piha) shortlisted the following novels:

Joel Haahtela: Katoamispiste (‘Vanishing point’, Otava), Markus Nummi: Karkkipäivä (‘Candy day’, Otava), Riikka Pulkkinen: Totta (‘True’, Teos), Mikko Rimminen: Nenäpäivä (‘Nose day’, Teos), Alexandra Salmela: 27 eli kuolema tekee taiteilijan (’27 or death makes an artist’, Teos) and Erik Wahlström: Flugtämjaren (in Finnish translation, Kärpäsenkesyttäjä, ‘The fly tamer’, Schildts). Here’s the FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange link to the jury’s comments.

Joenniemi noted the shortlisted books all involve problems experienced by people of different ages. How to be a consenting adult? How do adults listen to children? Contemporary society has been pushing the age limits of ‘youth’ upwards so that, for example, what used to be known as middle age now feels quite young. And, for example, in Erik Wahlström’s Flugtämjaren (now also on the shortlist for the Nordic Literature Prize 2011) the aged, paralysed 19th-century author J.L. Runeberg appears full of hatred: being revered as Finland’s national poet didn’t make him particularly noble-minded.

According to Joenniemi, Rimminen’s novel ‘takes a stand gently’ in its portrayal of contemporary life – in a city where a lonely person’s longing for human contacts takes on tragicomical proportions. Joenniemi finds Rimminen’s language ‘uniquely overflowing’. Its humour poses itself against the prevailing negative attitude, turning black into something lighter.

Rimminen has earlier published two collections of poems and two novels (Pussikaljaromaani, ‘Sixpack novel’, 2004, and Pölkky, ‘The log’, 2007) . Pussikaljaromaani has been translated into Dutch, German, Latvian, Russian and Swedish.

Solzhenitsyn and Silberfeldt: Sofi Oksanen publishes a best-seller

25 April 2012 | In the news

Nobel Prize 1970: Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

After falling out with her original publisher, WSOY, in 2010, author Sofi Oksanen – whose third novel, Puhdistus (Purge, 2008), has become an international best-seller – has founded a new publishing company, Silberfeldt, in 2011, with the aim of publishing paperback editions of her own books. Its first release was a paperback version of Oksanen’s second novel, Baby Jane.

Oksanen’s new novel, Kun kyyhkyset katosivat (‘When the pigeons disappeared’), again set in Estonia, will appear this autumn, published by Like (a company owned by Finnish publishing giant Otava).

However, in April Silberfeldt published a new, one-volume edition of the autobiographical novel The Gulag Archipelago by the Nobel Prize-winning author Alexandr Solzhenitsyn. This massive book was first published in the West in 1973, in the Soviet Union in 1989.

A Finnish translation was published between 1974 and 1978. Back in those days of Cold War self-censorship, Finnish publishers felt unable to take up the controversial book, and the first volume was eventually printed in Sweden. The work, finally published in three volumes, has long since been unavailable.

This time the 3,000 new copies of Solzhenitsyn’s tome sold out in a few days; a second printing is coming up soon. Oksanen regards the work as a classic that should be available to Finnish readers.

Funny peculiar

9 December 2011 | Articles, Comics, Non-fiction

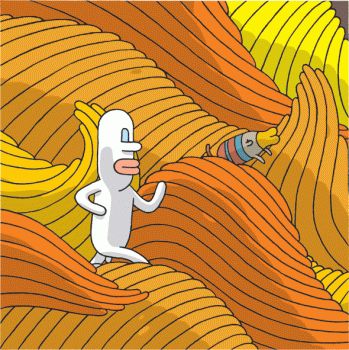

Samuel, the creation of Tommi Musturi (featured in Books from Finland on 7 May, 2010, entitled ‘Song without words’)

Comics? The Finnish word for them, sarjakuva, means, literally, ‘serial picture’, and lacks any connotation with the ‘comic’. The genre, which now also encompasses works called graphic novels, has been the subject of celebrations this year in Finland, where it has reached its hundredth birthday. Heikki Jokinen takes a look at this modern art form

Comics are an art form that combines image and word and functions according to its own grammatical rules. It has two mother tongues: word and image. Both of them carry the story in their own way. Images and sequences of images have been used since ancient times to tell stories, and stories, for their part, are the common language of humanity. The long dark nights of the stone age were no doubt enlivened by storytellers.

One of the pioneers of comics was the Swiss artist Rodolphe Töpffer. As early as 1837, he explained how his books, combinations of images and words, should be read: ‘This little booklet is complex by nature. It is made up of a series of my own line drawings, each accompanied by a couple of lines of text. Without text, the meaning of the drawings would remain obscure; without drawings, the text would remain without content. The whole gives birth to a sort of novel – but one which is in fact no more reminiscent of a novel than of any other work.’ More…

Tiia Aarnipuu: Jonkun on uskallettava katsoa. Animalian puoli vuosisataa [Someone’s got to dare to look. Half a century of Animalia]

28 July 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Jonkun on uskallettava katsoa. Animalian puoli vuosisataa

Jonkun on uskallettava katsoa. Animalian puoli vuosisataa

[Someone’s got to dare to look. Half a century of Animalia]

Helsinki: Like Kustannus, 2011. 209 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-01-0582-2

€ 33, paperback

This book has been published to mark the 50th anniversary of Animalia, the Federation for the Protection of Animals. The public image of the organisation has varied between one of a conservative club of ladies and gentlemen and that of a radical terrorist group. Animalia was founded in 1961, inspired by Johan Börtz, a Swede who gave lectures on the plight of animals used in experiments. Animalia began making visits to inspect animal testing facilities, which were completely unregulated in the early 1960s. Gradually the animal rights movement became more radicalised, somewhat later than in places such as Britain. Animal rights became a subject of wider debate in Finland in the 1980s. In the 1990s, the organisation was falsely linked with attacks made on fur farms by direct-action youth groups. Animalia’s stance has been to renounce vandalism and violence. In February 2010 Animalia launched its largest-ever information campaign, aimed at ridding Finland of fur farms by 2025.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

Too much, too soon?

20 January 2012 | This 'n' that

Candace Bushnell’s Summer & the City (about Carrie Bradshaw’s first years in NYC, published last year) is categorised among books for children and young people on the Finnish best-sellers’ list. The Finnish translation occupied the eighth place in December.

Candace Bushnell’s Summer & the City (about Carrie Bradshaw’s first years in NYC, published last year) is categorised among books for children and young people on the Finnish best-sellers’ list. The Finnish translation occupied the eighth place in December.

But hang on, wasn’t this Carrie in the fantastically famous HBO television adaptation of Bushnell’s novel Sex and the City very much in her thirties, as were her three best friends – all with, yes, quite active ‘adult’ sex lives…? In Finland the series had a rather silly title, Sinkkuelämää, ‘Single life’.

Well, of course it would be foolish not to continue the fantasticaly famous money-spinning saga, so Bushnell has gone back in time, first to Carrie’s school years in small-town America in The Carrie Diaries (2010), then to her first years in NYC in Summer & the City (2011) – and HarperCollins has pigeonholed them among its ‘teen books’.

Confusingly, the Finnish titles of these two books also contain the word referring to the television series: Sinkkuelämää – Carrien nuoruusvuodet and Sinkkuelämää – Ensimmäinen kesä New Yorkissa. As the Finnish publisher Tammi has attached TV title to them, the customer assumes these are books for ‘adults’ – as indeed was the original Sex and the City.

This makes one wonder what exactly ‘books for young people’ are. The main characters are teens themselves? If Bushnell goes still further back in time, we shall be reading about naughty Li´l Carrie hitting another toddler on the head with her doll, in a board book.

The Tollander Prize to Ulla-Lena Lundberg

17 February 2011 | In the news

One of the biggest literary prizes in Finland is the Tollander Prize, awarded annually on 5 February, the birthday of he national poet J.L. Runeberg, by Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland (the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland). The prize is worth €35,000.

The recipient of the 2011 Tollander Prize is Ulla-Lena Lundberg, a versatile writer of novels, short stories, poems and travel essays. ‘She moves freely in different landscapes, times and cultures, finding universality in locality, whether on the island of Kökar in Åland, in Africa or in Siberia’, said the jury.

Written between 1989 and 1995, Lundberg’s fictional trilogy of Leo, Stora världen (‘The big world’) and Allt man kan önska sig (‘Everything one can wish for’), focused on the seafaring history and evolution of shipping in the Finnish Åland islands. Her autobiographical work Sibirien (Siberia’, 1993) has been published in German, Danish and Dutch.

Read the extracts from her latest book, Jägarens leende (‘Smile of the hunter’, 2010), on rock art, reviewed on our pages by Pia Ingström.

Asko Sahlberg: Häväistyt [Disgraced]

2 February 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Häväistyt

Häväistyt

[Disgraced]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2011. 331 p.

ISBN 978-951-0-38275-2

€ 33, hardback

The tenth novel by Asko Sahlberg (born 1964) is reminiscent of the earlier works of this distinctive author: its principal characters are hardened by experience and lead their lives somewhere in the Finnish countryside during a recent period of the country’s history. The sentences are beautifully constructed, and the pace of the narrative is very slow – sometimes even too slow. The main role is played by a middle-aged man who is running away with a woman and a small boy. What they are running away from for a long time remains a puzzle, as does the question of who they are looking for, a man called The Master. In the flashbacks of the last part of the book all is explained, and the rhythm of the story quickens. Considering the book’s desolate, even fatalistic view of the world, it is slightly surprising that everything eventually turns out as happily as in a fairytale. But perhaps this is Sahlberg’s tribute to his characters, and to all of us human beings, for whom he seems to care a great deal? His novel He (2010) will be published in February in England under the title The Brothers (Peirene Press).

Translated by David McDuff

Christmas best-sellers in Finnish fiction

13 January 2012 | In the news

Rosa Liksom. Photo: Pekka Mustonen

Most new Finnish books are printed and sold in the autumn, and sales pick up considerably in December. The number one on the December list link: in Finnish only) of best-selling fiction titles in Finland, compiled by the Finnish Booksellers’ Association, is the Finlandia Fiction Prize-winning novel Hytti nro 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY, 2011) by Rosa Liksom (this is her homepage, also in English).

The Finlandia winner was announced on 1 December, upon which the book shot – from nowhere – to the top of the list.

Laila Hirvisaari’s historical novel, Minä Katariina (‘I, Catherine’, Otava), climbed up from the third place to the second. Number three was a newcomer, a tragic love story entitled Kätilö (‘The midwife’, WSOY), by Katja Kettu, set in the last phase of the Finnish Continuation War (1941–1944).

Jari Tervo’s Layla (WSOY) was in fourth place, while November’s number one, Ilkka Remes’s thriller Teräsleijona (‘Steel lion’, WSOY), came fifth.

In November Tuomas Kyrö occupied both the fourth and the tenth place with his novels Kerjäläinen ja jänis (‘The beggar and the hare’, Siltala – a pastiche-style story inspired by Jäniksen vuosi / The Year of the Hare by Arto Paasilinna, 1975) and Mielensäpahoittaja (‘Taking offence’, WSOY, 2010). In December they were numbers six and seven, in reverse order.

Utopia or cacotopia?

19 August 2011 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Viljakansaari, Finland, 2008. ©Merja Salo

Do we live in the age of autopia, and if we do, what does that mean? On this earth there are now perhaps 800 million cars, all vital to our modern lifestyles. Professor and photographer Merja Salo observes landscapes through her camera with this question in mind

Extracts and photographs from Carscapes. Automaisemia (Edition Patrick Frey & Musta Taide, 2011. Translation: Laura Mänki)

The car may be the vehicle for the everyman, but not every man is a good driver. According to Hungarian- born psychoanalyst Michael Balint, good drivers have the psychological structure of philobats. With their sense of sight, they perceive space well and control it by steering their vehicle skilfully. Ocnophiles, on the other hand, are more at home as passengers. They structure the world through intimacy and touch. When driving, they cling anxiously to the steering wheel and do not perceive the continously changing situations in traffic.

Ulla Jokisalo & Anna Kortelainen

Pins and needles

11 May 2011 | Essays, Non-fiction

In these pictures by Ulla Jokisalo and texts by Anna Kortelainen, truths and mysteries concerning play are entwined with pictures painted with threads and needles. Jokisalo’s exhibition, ‘Leikin varjo / Guises of play’, runs at the Museum of Photography, Helsinki, from 17 August to 25 September.

Words and images from the book Leikin varjo / Guises of play (Aboa Vetus & Ars Nova and Musta Taide, 2011)

‘Ring dance’ by Ulla Jokisalo (pigment print and pins, 2009)

Funny ha ha?

3 March 2010 | This 'n' that

Comic books, graphic novels: the popularity of stories in pictures keeps on growing everywhere – and they may or not may be ‘comical’.

Comic books, graphic novels: the popularity of stories in pictures keeps on growing everywhere – and they may or not may be ‘comical’.

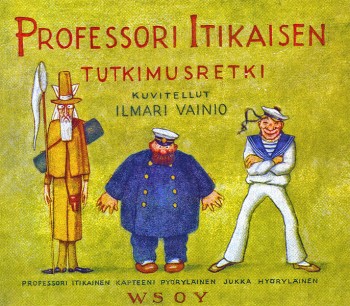

In Finland, sarjakuva (lit. serial picture) will celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2011. The first Finnish picture story, Professori Itikaisen tutkimusretki (‘Professor Itikainen’s expedition’, WSOY), by Ilmari Vainio, was published in 1911.

Ilmari Vainio (1892–1955) was a customs official who later also published two fairy tales and two handbooks for boy scouts. Professor Itikainen is a scientist who sets out on the sea and then finds himself, together with two brave seamen, facing various dangers in Africa, China and on the North Pole. A happy ending ensues in the form of safe arrival back in Helsinki on page 48. More…

Indifference under the axe

9 March 2012 | Essays, Non-fiction

In the forest: an illustration by Leena Krohn for her book, Sfinksi vai robotti (Sphinx or robot, 1999)

The original virtual reality resides within ourselves, in our brains; the virtual reality of the Internet is but a simulation. In this essay, Leena Krohn takes a look at the ‘shared dreams’ of literature – a virtual, open cosmos, accessible to anyone, without a password

How can we see what does not yet exist? Literature – specifically the genre termed science fiction or fantasy literature, or sometimes magic realism – is a tool we can use to disperse or make holes in the mists that obscure our vision of the future.

A book is a harbinger of things to come. Sometimes it predicts future events; even more often it serves as a warning. Many of the direst visions of science fiction have already come true. Big Brother and the Ministry of Truth are watching over even greater territories than in Orwell’s Oceania of 1984. More…

What grade is your kid in?

29 October 2010 | Non-fiction, Tales of a journalist

Should a journalist show his hand? Columnist Jyrki Lehtola ponders the pros and cons of showing one’s true political colours

What’s the best way to present an initiative that would get the cynical, lazy news media to take an interest in the outside world?

The easiest way is to make a proposal in which the outside world is actually defined as the news media itself.

This is exactly what Matti Apunen did early this autumn: Apunen, a long-time journalist and the former editor-in-chief of the Aamulehti newspaper, had just left the paper to lobby for Finnish industry and trade interests as director of the Finnish Business and Policy Forum EVA.

He presented the Finnish media with a straw poll, following the Swedish model, in which reporters would anonymously answer questions about their political leanings. More…

Finland, cool! The Frankfurt Book Fair 8–12 October

30 September 2014 | Articles, Non-fiction

Finnland. Cool. pavilion in Frankfurt, designed by Natalia Baczynska Kimberley, Nina Kosonen and Matti Mikkilä from Aalto University

It starts next week: Finland is Guest of Honour at the Book Fair in the German and global city of Frankfurt. This link will take you to it all.

Approximately 170,000 professionals from the literary world are expected to visit the exhibition halls from Wednesday to Friday; the weekend is reserved for the general public, c.100,000 visitors. Since 1980s different countries have been in focus each year. More…

C.L. Engel. Koti Helsingissä, sydän Berliinissä. C.L. Engel. Hemmet i Helsingfors, hjärtat i Berlin [C.L. Engel. Home in Helsinki, heart in Berlin]

23 February 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

C.L. Engel. Koti Helsingissä, sydän Berliinissä. C.L. Engel. Hemmet i Helsingfors, hjärtat i Berlin

C.L. Engel. Koti Helsingissä, sydän Berliinissä. C.L. Engel. Hemmet i Helsingfors, hjärtat i Berlin

[C.L. Engel. Home in Helsinki, heart in Berlin]

Tekstit [Texts by]: Matti Klinge, Salla Elo, Eeva Ruoff

Valokuvat [Photography]: Taavetti Alin & Risto Törrö

Översättning [Translations from Finnish into Swedish]: Ulla Pedersen Estberg

Helsingfors: Schildts, 2012. 140 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-50-2183-0

€ 31.50, hardback

The life and works of the German architect Carl Ludvig Engel (1778–1840) are portrayed in four articles by specialists in Finnish history, the history of Helsinki and the history of gardens. Engel spent almost 24 years in Helsinki, transforming it with his architectural designs. For eleven of those years, he and his family lived in a house surrounded by a large garden, both of them his own creations. Looking for work, the young Engel finally found it in the tiny northern town that was pronounced the new capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland in 1812 – both Tsar Alexander I and his successor, Nikolai I, favoured him. From 1816 onwards he designed more than twenty neo-classical buildings, among them nationally important landmarks: the Cathedral, the City Hall, the National Library and the University. Despite his mostly rewarding job as a highly regarded city planner, Engel found Helsinki cold, small and quiet, and he constantly longed for his native Berlin, which he never saw again. However, his flourishing garden gave him great pleasure. Richly illustrated with photographs, the book gives the reader an thorough and interesting picture of this city-changing man and his era.