Search results for "2010/05/song-without-words"

I, Vega Maria Eleonora Dreary

30 December 2008 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Chitambo (Schildts, 1933)

I was born in 1893, of course. That, as everyone knows, is the proudest year in the history of Nordic polar research. It was the year in which Fridtjof Nansen began his world-famous voyage to the North Pole aboard the Fram. Mr Dreary viewed this as a personal distinction and a sign that fate had fixed its gaze on him. He at once took it for granted that I was destined for great things, and he showed much skill in fostering the same foolish idea in me…. More…

The unicorn

30 September 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Koira nimeltä Onni ja muita onnettomuuksia (’A dog called Lucky and other misfortunes’, Tammi, 1997)

Hilma was rattling her bars when Pirjo stepped into the ward. Once again, she was the only one awake. The three other old people were asleep, wheezing heavily through their toothless mouths, making the air thick with their breathing. Clutching the bars of her bed, Hilma clambered up to a sitting position and leaned her sparse hair against the side.

‘How are you doing with the medicine?’ Pirjo asked.

‘A mouse took it,’ Hilma said, fixing her with her eyes.

‘And you’re not at all sleepy,’ Pirjo sighed. More…

The devil has no clothes

31 December 2006 | Fiction, poetry

Poems from Idealrealisation (‘The ideal sale’, 1929)

Stockings

V

I thought:

it was a person,

but it was her clothes

and I didn't know

that it doesn't matter

and that clothes can be very

beautiful

Damned nihilists

30 December 2008 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Much misunderstood: father of the superman, Friedrich Nietzsche.

The term nihilism is often bandied about, but often badly misunderstood. In extracts from his new book, Ei voisi vähempää kiinnostaa. Kirjoituksia nihilismistä (‘Couldn’t care less. Writings on nihilism’, Atena, 2008), the social scientist and philosopher Kalle Haatanen discusses the true legacy of Friedrich Nietzsche, nihilism’s high priest

The word nihilist is derived from the Latin: ‘nihil’ means, simply, ‘nothing’. When someone is labelled as nihilist or seen as representing nihilism, this has always been a curse, a mockery or an accusation, whether in philosophy, politics or everyday conversation. More recently, the word has generally been used to refer to people who do not believe in anything – people whose world-view is without principle, without ideals, barren. More…

Notes related to pharmacist Pemberton’s holy nectar

Extracts from the novel Vådan av att vara Skrake (‘The perils of being Skrake’, Söderström & Co.; Isän nimeen, Otava, 2000)

At the time of Werner’s stay in Cleveland Bruno and Maggie had already been divorced for some years, and in an irreconcilable manner. But they were still interested in their grown-up son, each in their own way; Maggie wrote often, and Werner replied, he wrote at length, and truthfully, for he knew that Bruno and Maggie no longer communicated; to Maggie he could admit that he hated corporate law and bookkeeping, and to her he dared to talk about the raw music he had found on the radio station WJW, he wrote to her that the music of the blacks had body and that he had found a great record store, it was called Rendezvous and was situated on Prospect Avenue and there he had also bought a ticket for a blues concert, wrote Werner, he thought that Maggie would understand. More…

Sound and meaning

20 January 2012 | Essays, Non-fiction

Harri Nordell’s poem from Huuto ja syntyvä puu (‘Scream and tree being born’, 1996)

Translating poetry is natural, claims Tarja Roinila; it is a continuation of writing it, for works of poetry are not finished, self-sufficient products. But is the translator the servant of the meaning – or of the letter?

I am sitting in a cafe in Mexico City, trying to explain in Spanish what valokupolikiihko, ‘light-cupola-ecstasy’, means. And silmän valokupolikiihko, ‘the light-cupola-ecstasy of the eye’.

I take to praising the boundless ability of the Finnish language to form compound words, to weld pieces together without finalising the relationships between them, never mind establishing a hierarchy: the eye is a light-cupola, the eye is ecstatic about light-cupolas, light creates cupolas, the cupola lets out the light, the eye, in its ecstasy, creates a light-cupola. More…

In the detail?

11 December 2009 | Essays, Non-fiction

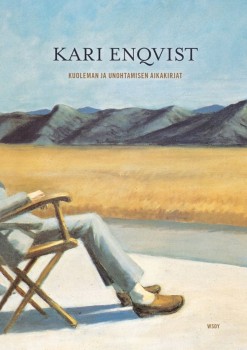

Extracts from Kuoleman ja unohtamisen aikakirjat (‘Chronicles of death and oblivion’, WSOY, 2009)

Extracts from Kuoleman ja unohtamisen aikakirjat (‘Chronicles of death and oblivion’, WSOY, 2009)

What’s the meaning of life? There are those who seek it in religion, while for others that is the last place to look. The scientist Kari Enqvist ponders why some people, including himself, seem physiologically immune to the lure of faith. Perhaps, he suggests, we should look for significance not in the big picture, but in the marvel of the fleeting moment

As a young boy I must have held religious beliefs. However, I cannot pinpoint exactly when they disappeared. At some point I eventually stopped saying my evening prayers, but I am unable to remember why or when this happened. ‘I was born in a time when the majority of young people had lost faith in God, for the same reason their elders had had it – without knowing why,’ writes the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa in The Book of Disquiet. More…

Words like songs

The Finnish poet Helvi Juvonen (1919–1959) often studies small things: moles, lichen, bees and dwarf trees; she ‘doesn’t often dare to look at the clouds’. But small is beautiful; her nature poems and fairy-tales mix humility and the celebration of life. Commentary by Emily Jeremiah

Cup lichen

Luke 17:21

The lichen raised its fragile cup,

and rain filled it, and in the drop

the sky glittered, holding back the wind.

The lichen raised its fragile cup:

Now let’s toast the richness of our lives.

From Pohjajäätä [‘Ground-ice’], 1952) More…

The guest book

30 June 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract rom the novel Kenen kuvasta kerrot (‘Whose picture are you talking about’, Otava, 1996). Introduction by Pia Ingström

Late at night before going to bed An Lee had turned off all the lights, opened the large bedroom window, breathed the cool air. She had done this often. It made it easier to fall asleep. It was enough to look outside for a moment and to breathe in slowly, and at the same time the bedroom air freshened and changed for the night.

Then she had closed and locked the window, drawn the curtains, and switched on the dim wall light. It might be nice to decorate the space between the double windowpanes with wooden animals, she had thought, not for the first time. They had had some at home, her mother had been a collector of such things. Almost all of them pink and lemon yellow, a whole zoo between the windows, only the panther had been pitch-black, and on one of the elephants the pretty grey color had been scratched and splotchy on one side. More…

In the early hours

31 March 1976 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Dyre Prins (‘Sweet Prince’, 1975). Introduction by Ingmar Svedberg

Donald Blaadh, a retired businessman, has been called to visit an influential acquaintance in the middle of the night.

He was sitting in the library, listening to Shostakovich, the Leningrad Symphony. The slow crescendo. The insistent march rhythm. Dogged endurance. Indomitability. He switched it off when I came in.

“I can’t sleep,” he said.

“Neither can I.”

He ignored the ironic undertone. “Shostakovich sharpens the decisionmaking faculties, the way chess sharpens the wits,” he said. “A sort of exercise routine … but I forgot, you don’t play chess.”

“No, but I do play the gramophone.”

“To-day I’m going to start you off with a quiz: whose immortal words were these, ‘Minerva’s owl never takes to the air till twilight is falling’?”

“I don’t know.” More…

Cut time, paste space

12 September 2013 | Articles, Non-fiction

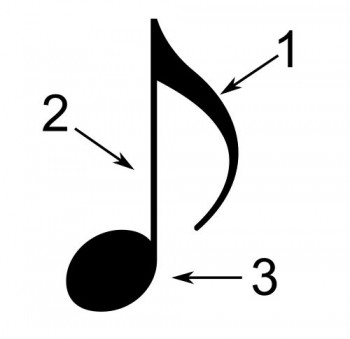

Back to basics. Parts of a musical note. Picture: Wikimedia

How different are the art of words and the art of sounds, author Teemu Manninen ponders, as he unexpectedly finds himself in the role of a musician in a performance. Time, space or both?

Some time ago I got the chance to participate in an unusual concert – as a performer: six players, myself included, were grouped around a table with a triangle in one hand and a glove in the other. Pieces of dry ice and a bucket of water were placed in front of each of us.

The performance began: we took a piece of dry ice and pressed it against the triangle. As the metal cooled, it burned through the ice, releasing gas, which in turn made the metal vibrate very fast. This produced a keening sound that filled the room. More…

So many words

25 April 2012 | Articles, Non-fiction

Hagia Sofia, Istanbul: from basilica to cathedral to mosque to museum. Postcard, c. 1914. Photo: Wikipedia/Xenophon

Sacred spaces, repositories of free speech, places of healing? Teemu Manninen awaits the day when libraries become virtual, enabling anybody to visit them, without having to travel across land and sea

The Bodleian Library in Oxford, the Vatican Library, the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, New York Public Library, the British Museum Reading Room, the Real Gabinete Portugues De Leitura in Rio De Janeiro, the Library of Congress and the National Library of Finland.

What do all of these have in common, except the obvious fact that they are all famous libraries? To put it another way: why are these famous libraries so famous?

It is not because they have books in them, although that has become one of the main tasks of the library system in the modern world. But a library is not simply an archive. If we in the West are a culture of the book – a culture of the freedom of information and expression – then a library is the architectural incarnation of our way of life: a church built for reading. More…

A light shining

28 July 2011 | Essays, Non-fiction

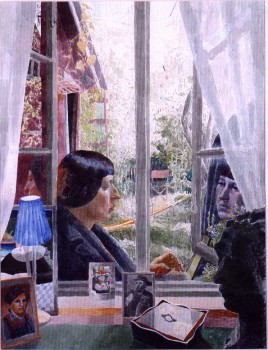

Portrait of the author: Leena Krohn, watercolour by Marjatta Hanhijoki (1998, WSOY)

In many of Leena Krohn’s books metamorphosis and paradox are central. In this article she takes a look at her own history of reading and writing, which to her are ‘the most human of metamorphoses’. Her first book, Vihreä vallankumous (‘The green revolution’, 1970), was for children; what, if anything, makes writing for children different from writing for adults?

Extracts from an essay published in Luovuuden lähteillä. Lasten- ja nuortenkirjailijat kertovat (‘At the sources of creativity. Writings by authors of books for children and young people’, edited by Päivi Heikkilä-Halttunen; The Finnish Institute for Children’s Literature & BTJ Kustannus, 2010)

What is writing? What is reading? I can still remember clearly the moment when, at the age of five, I saw signs become meanings. I had just woken up and taken down a book my mother had left on top of the chest of drawers, having read to us from it the previous day. It was Pilvihepo (‘The cloud-horse’) by Edith Unnerstad. I opened the book and as my eyes travelled along the lines, I understood what I saw. It was a second awakening, a moment of sudden realisation. I count that morning as one of the most significant of my life.

Learning to read lights up books. The dumb begin to speak. The dead come to life. The black letters look the same as they did before, and yet the change is thrilling. Reading and writing are among the most human of metamorphoses. More…