Search results for "pentti saarikoski"

Figuring out father

18 October 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

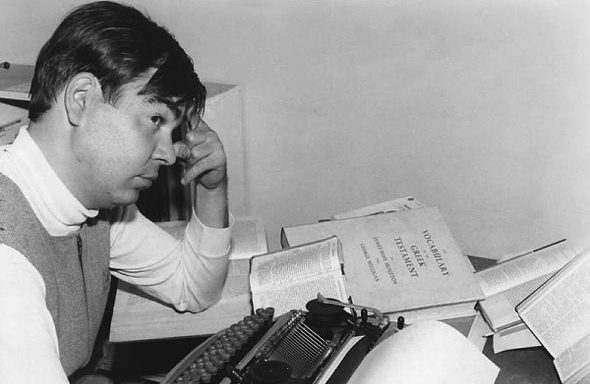

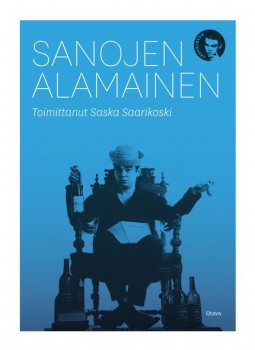

Pentti Saarikoski (1960s). Photo: Otava/Nikolai Naumoff

The poet and translator Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) jotted in one of his journals: ‘I have never cared for relatives.’ Thirty years after his death one of his five children set out to find out what his father was like – by reading almost all he left behind in writing; these comments by Saska Saarikoski are from his Sanojen alamainen (‘Servant of words’, Otava, 2012), an annotated selection of Pentti Saarikoski’s thoughts

Pentti Saarikoski died when I was 19. I remember complaining to my mother that I had not yet even got to know my dad. My mother answered: You’ve got plenty of time, the real Pentti is to be found in his books. She did not know how right she was, for she meant Pentti’s published books, not knowing what a mountain of texts awaited its readers in the archives of the Finnish Literature Society. Pentti had written everything down in his diaries.

I read Nuoruuden päiväkirjat (‘Youthful diaries’), published soon after Pentti’s death in 1983, as soon as they were published, but when his Prague, Drunkard’s and Convalescent’s Diaries appeared around the millennium, they went straight on to my library shelf. I was not terribly interested in the ramblings of Pentti’s alcoholic years.

It could be that my reluctance was influenced by the cool attitude I had adopted from early on in relation to my father. Other people were welcome to consider him a genius; for me, he was a father who did not telephone, write or come to see my football matches. I didn’t call him, either; for me, it was a father’s job. More…

Three short stories

30 June 1987 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

from Väärinkäsityksiä (‘Misconceptions’). Interview by Markku Huotari

Love

Kaija couldn’t understand why she felt like laughing all the time.

‘As for me, what I stand for is good old-fashioned courtesy,’ he pointed out.

He’d got a soft, low, caressing voice. He rested his hand on Kaija’s shoulder. They’d got that far already. Kaija had decided to say yes, even though he hadn’t suggested anything yet. She was beginning to picture luxurious rooms, gourmet dishes, expensive drinks, and tender, passionate lovemaking.

‘Socially I’m a radical,’ he said. ‘Culturally a liberal, but in personal things an unshakeable conservative. A woman, in my view, is to be respected – I don’t consider that damaging to her independence. Too often, in today’s world, equality’s used to justify what are quite simply bad manners.’ More…

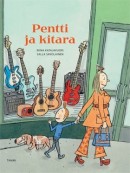

Riina Katajavuori & Salla Savolainen: Pentti ja kitara [Pentti and the guitar]

9 January 2014 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Pentti ja kitara

Pentti ja kitara

[Pentti and the guitar]

Kuvitus [Ill. by]: Salla Savolainen

Helsinki: Tammi, 2013. 32 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-951-31-6646-5

€22.90, hardback

Even early-years education is packed with activities these days. Pentti has a large extended family who really know how to have fun. He wants to learn how to play the guitar as well as his uncle Jaska. His mum tries to suggest an instrument she thinks would be more appropriate, but Pentti will not be put off. The Pentti picture book series is attractive for its nostalgic style; you can never be quite sure whether the era depicted is in the past or the present day. In this story, Riina Katajavuori focuses on what’s essential, yet still manages to convey the basics of playing the guitar – including dissonance and Jimi Hendrix. Salla Savolainen’s illustrations effectively capture the excitement of a child’s new hobby.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

Government Prize for Translation 2011

24 November 2011 | In the news

María Martzoúkou. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

The Finnish Government Prize for Translation of Finnish Literature of 2011 – worth € 10,000 – was awarded to the Greek translator and linguist María Martzoúkou.

Martzoúkou (born 1958), who lives in Athens, where she works for the Finnish Institute, has studied Finnish language and literature as well as ancient Greek at the Helsinki University, where she has also taught modern Greek. She was the first Greek translator to publish translations of the Finnish epic, the Kalevala: the first edition, containing ten runes, appeared in 1992, the second, containing ten more, in 2004.

‘Saarikoski was the beginning,’ she says; she became interested in modern Finnish poetry, in particular in the poems of Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983). As Saarikoski also translated Greek literature into Finnish, Martzoúkou found herself doubly interested in his works.

Later she has translated poetry by, among others, Tua Forsström, Paavo Haavikko, Riina Katajavuori, Arto Melleri, Annukka Peura, Pentti Saaritsa, Kirsti Simonsuuri and Caj Westerberg.

Among the Finnish novelists Martzoúkou has translated are Mika Waltari (five novels; the sixth, Turms kuolematon, The Etruscan, is in the printing press), Väinö Linna (Tuntematon sotilas, The Unknown Soldier) and Sofi Oksanen (Puhdistus, Purge).

María Martzoúkou received her award in Helsinki on 22 November from the minister of culture and sports, Paavo Arhinmäki. Thanking Martzoúkou for the work she has done for Finnish fiction, he pointed out that The Finnish Institute in Athens will soon publish a book entitled Kreikka ja Suomen talvisota (‘Greece and the Finnish Winter War’), a study of the relations of Finland and Greece and the news of the Winter War (1939–1940) in the Greek press, and it contains articles by Martzoúkou.

The prize has been awarded – now for the 37th time – by the Ministry of Education and Culture since 1975 on the basis of a recommendation from FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange.

Reading matters? On new books for young readers

9 January 2014 | Articles, Children's books, Non-fiction

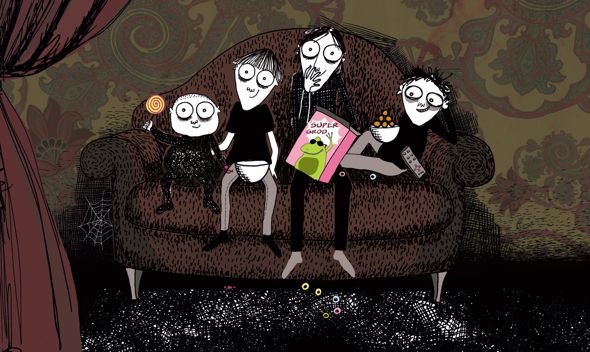

The Pixon brothers don’t read books, they love the telly: story by Malin Kivelä, illustrations by Linda Bondestam (Bröderna Pixon och TV:ns hemtrevliga sken, ‘The Pixon brothers and the homely shimmer of the telly’)

Finnish picture books for children have long been reliable export goods around the world. In the last few years, a number of novels for children have come along in their wake: works by authors such as Timo Parvela and Siri Kolu have been translated into a good many languages.

Now young adult literature has also blazed a trail on to the international market – in what also seems to be almost a matter of precision timing with regard to the Frankfurt Book Fair 2014. Finnish publishers have been investing in their home-grown lists of children’s and young adult books ever since the turn of the millennium, and now the time has come to harvest the fruits of their long-term efforts.

Nine lives

30 September 1994 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Entire lives flash by in half a page in this selection of very short short stories. Extracts from Elämiä (‘Lives’, Otava, 1994)

Silja

Silja was born in 1900. The home farm had been sub-divided many times. Silja threw a piece of bread on the floor. ‘Don’t sling God’s corn,’ said grandmother. Silja got up to go to school at four. In the cart, her head nodded; when the horse was going downhill its shoes struck sparks in the darkness. Silja’s brother drove to another province to go courting. Silja sat in the side-car. ‘The birches were in full leaf there,’ she said at home. Silja went to Helsinki University to read Swedish. She saw the famous Adolf Lindfors playing a miser on the big stage at the National Theatre. Silja got a senior teaching post at the high school. With a colleague, she travelled in Gotland. Silja donated her television set to the museum. It was one of the first Philips models. ‘Has this been watched at all?’ they asked Silja. Silja learned to drive after she retired. She called her car ‘The Knight’. The teachers’ society made a theatre trip to Tampere. Silja looked up her colleague in the telephone directory in the interval. There was no one of that name. More…

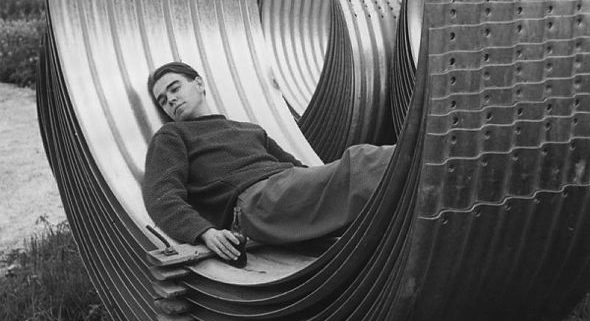

Pentti Sammallahti & Finn Thrane

Here, now

1 October 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Beijing, China, 1989. Photo: Pentti Sammallahti

Photographer Pentti Sammallahti (born 1950) has travelled widely over six decades; his mostly black-and-white photographs portray humans, animals, cities as well as open landscapes, in Nepal, France, Kalmykia, the US, Morocco, Russia – in more than 40 countries. His beautifully executed retrospective work, entitled ‘here far away’, containing more than 250 photographs, is introduced by Finn Thrane

Here far away is a retrospective work that comprises nearly fifty years of photographic activity and unfolds in almost as many countries. Despite this, Pentti Sammallahti’s discreet title points to the paradox that the photograph always represents a here-and-now: an encounter in the exhibition or on the page of the book between artist and viewer, which is of course subject to the law of mutability, but constantly reflects the capacity of the two to enter into a dialogue, to extend the picture’s mirror of the past into the viewer’s present and future. More…

Fair game

23 October 2009 | This 'n' that

Words for sale: Helsinki Book Fair, 2009. - Photo: Suomen Messut / Kimmo Brandt

The Helsinki Book Fair opened yesterday (22 October), with the theme ‘What’s really happening’, at the Helsinki Exhibition and Convention Centre. Over four days there will be more than a thousand performers (mostly writers and their interviewers) and nearly 300 exhibitors. Last year’s Fair attracted 68,000 visitors.

The words of the theme are borrowed from a 1960s collection of poems (Mitä tapahtuu todella) by Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983). According to the press release, the theme ‘sums up what literature is about’; moreover, ‘fiction and non-fiction reflect this very day, reinterpreting the past and present glimpses of what is to come’.

What’s really happening, it seems to us, is that inventing catchy titles for commercial purposes is an enterprise that should be undertaken with caution, as it may produce unintentional connotations for the delectation of those in the know… Mitä tapahtuu todella – its title borrowed in turn from none other than the Russian revolutionary Vladimir Ilyich Lenin – was a politically utopian collection in which Saarikoski expressed his belief in dialectical materialism and communism, contrasting American avant-garde art with the Marxist-Leninist utopia in which the writer wished to live.

In recognition of bicentennial 1809, the year in which Finland ceased to be part of the kingdom of Sweden and became an autonomous Grand Duchy of Russia, Sweden is under focus at the Book Fair, and is represented by 27 exhibitors and more than 30 performers. Writers from eight countries in all will visit the Fair, Russia taking part for the first time. Among the visitors are the writers Andrei Astvatsaturov and Herman Sadullajev and the translators Lyudmila Braude ja Anna Sidorova, who were awarded this year’s Finnish Government Prize for Translation.

The Fair is organised by The Finnish Fair Corporation in conjunction with the Finnish Book Publishers Association and the Organisation of the Booksellers Association of Finland.

The poet and translator Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) was a legend in his own lifetime, a media darling, a public drinker who had five children with four women. His oeuvre nevertheless encompasses 30 works, and his translations include Homer and James Joyce. The journalist Saska Saarikoski (born 1963) has finally read all that work – in search of the father whom he seldom met. The following samples are from his annotated selection of Pentti Saarikoski’s thoughts over 30 years, Sanojen alamainen (‘Servant of words’, Otava, 2012; see

The poet and translator Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) was a legend in his own lifetime, a media darling, a public drinker who had five children with four women. His oeuvre nevertheless encompasses 30 works, and his translations include Homer and James Joyce. The journalist Saska Saarikoski (born 1963) has finally read all that work – in search of the father whom he seldom met. The following samples are from his annotated selection of Pentti Saarikoski’s thoughts over 30 years, Sanojen alamainen (‘Servant of words’, Otava, 2012; see