Search results for "Riikka/2010/10/mikko-rimminen-nenapaiva-nose-day"

Finlandia Junior Prize 2010

26 November 2010 | In the news

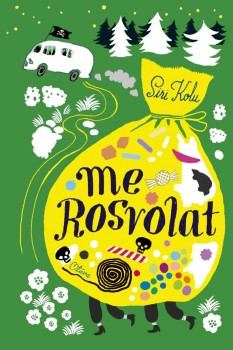

The Finlandia Junior Prize has gone to author Siri Kolu and illustrator Tuuli Juusela for the novel Me Rosvolat (‘Me and the Robbersons’, Otava); they will share the award of €30,000 (see the Prize jury assessments of the shortlist here). The winner was chosen by actor and writer Hannu-Pekka Björkman.

The Finlandia Junior Prize has gone to author Siri Kolu and illustrator Tuuli Juusela for the novel Me Rosvolat (‘Me and the Robbersons’, Otava); they will share the award of €30,000 (see the Prize jury assessments of the shortlist here). The winner was chosen by actor and writer Hannu-Pekka Björkman.

Awarding the prize on 25 November he said: ‘It caught my attention that in none of the six shortlisted children’s books are there any so-called nuclear families, at least not for long. The main characters constantly live and grow without something – the lack of parents or the attention of an adult is a serious matter to a child. However, in these books there is always someone who cares, not perhaps a stereotypical mom or dad, but an adult nevertheless.’ In Björkman’s opinion Me Rosvolat, with its rich language and a whiff of anarchy, presents the reader with moments of realisation and wonderment.

Snowbirds

2 November 2011 | Extracts, Non-fiction

The short winter days of the northerly latitudes are made brighter by snow cover, which almost doubles the amount of available light. Reflection from the snow is an aid for photographers working outdoors in winter conditions. A new book, entitled Linnut lumen valossa (‘Birds in the light of snow’), presents the best shots by four professionals, Arto Juvonen, Tomi Muukkonen, Jari Peltomäki and Markus Varesvuo, who specialise in patiently stalking the feathered survivors in the cold

The photographs and texts are from the book Linnut lumen valossa (‘Birds in the light of snow’, edited by Arno Rautavaara. Design and layout by Jukka Aalto/Armadillo Graphics. Tammi, 2011)

Snowy owl. Photo: Markus Varesvuo, 2010

Daddy’s girl

30 September 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Maskrosguden (‘The dandelion god’, Söderströms, 2004). Introduction by Maria Antas

The best cinema in town was in the main square. The other was a little way off. It was in the main square too, but you couldn’t compare it to the Royal. At the Grand there was hardly any room between the rows, the floor was flat and there was a dance-hall on the other side of the wall, so that Zorro rode out of time with waltzes, in time with oompahs, out of time with the slow steps of tangos and in time with quick numbers. The Royal was different and had a sloping floor.

Inside, the Royal was several hundred metres long. You could buy sweets on one side and tickets on the other. From Martina Wallin’s mum. She was refined. So was everyone except us: Mum, Dad and me. More…

Misery me

Extracts from the collection of short prose, Mielensäpahoittaja (‘Taking offense’, WSOY, 2010)

Past pushing up daisies

Well, yeah, so I took offense when the doctor said that considering my age I’m in tip-top shape. His theory was that my 25-kilometre ski circuits would keep an old coot like me in shape, if they didn’t kill me first. He said if I were to start just sitting on the couch and waiting, then the Reaper would be on my back in no time.

I don’t ski for my health. I ski because it’s pretty in the forest, and when a body is sweating he doesn’t think a whole lot. More…

A perfectly ordinary day

30 September 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extract from the novel Kello 4.17 (‘The time was 4.17’, WSOY, 1996). When time loses its meaning, real fear strikes like an iron glove. Aho writes about a man who is different but no outcast

I was lost to myself, if it is possible to be lost if you haven’t gone anywhere. Black birds curved through my mind and it felt as if no one needed me, no one or nothing: my mother bought clothes and make-up and did not seem to care; Uncle Lasse looked after the family business, steam coming out of his head, and kept shopkeepers and shopaholic customers happy; smiling bank managers slapped shy loan applicants encouragingly on the back, the gross national product grew without me having anything to do with it, or because I didn’t; and politics plodded onward as the mud squelched comfortingly. The machine of society hummed and ticked and Finland was as round and fat as a bomb. I looked at it and nothing changed, and on Sundays it was so quiet that you could look out of the window and see the Sahara.

A roof with a view

27 August 2009 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Mistä on mustat tytöt tehty? (‘What are black girls made of?’, Tammi, 2009) Introduction by Tuomas Juntunen

I’m a chimney sweep’s daughter, born October 1962 as a gift, a light to a darkened world. I’ve had lots of mothers, but none of them ever stuck around for good. One of them gave birth to me, so she’s Mother, not mother. Her name is Dewdrop, because water has spilled over the only photograph of My Mother and now her face has dissolved into a single translucent droplet; her nose, cheeks and chin are now a fat, shiny blob that looks like it’s about to fall out of the bottom of the picture. More…

What the snail thought

30 September 2005 | Fiction, Prose

Poems from Tapahtui Tiitiäisen maassa

(‘It happened in Tumpkin land’, WSOY, 2004)

Illustrations by Christel Rönns

Meritähti

Eli merenpohjassa Meritähti

tuhat tonnia vettä yllä.

- Minä jaksan kyllä,

sanoi Meritähti.

- On terävät sakarat,

ja litteät pakarat

ja paineenkestävät kakarat!

Elina Brotherus & Riikka Ala-harja

The passing of time

2 March 2015 | Extracts, Fiction, Prose

In 1999 the Musée Nicéphore Niépce invited the young Finnish photographer Elina Brotherus to Chalon-sur-Saône in Burgundy, France, as a visiting artist.

After initially qualifying as an analytical chemist, Brotherus was then at the beginning of her career as a photographer. Everything lay before her, and she charted her French experience in a series of characteristically melancholy, subjective images.

Twelve years on, she revisited the same places, photographing them, and herself, again. The images in the resulting book, 12 ans après / 12 vuotta myöhemmin / 12 years later (Sémiosquare, 2015) are accompanied by a short story by the writer Riikka Ala-Harja, who moved to France a little later than Brotherus.

In the event, neither woman’s life took root in France. The book represents a personal coming-to-terms with the evaporation of youthful dreams, a mourning for lost time and broken relationships, a level and unselfpitying gaze at the passage of time: ‘Life has not been what I hoped for. Soon it will be time to accept it and mourn for the dreams that will never come true. Mourn for the lost time, my young self, who no longer exists.’

1999 Mr Cheval’s nose

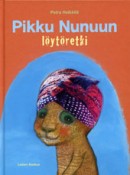

Petra Heikkilä: Pikku Nunuun löytöretki [Little Nunuu’s treasure hunt]

1 February 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Pikku Nunuun löytöretki

Pikku Nunuun löytöretki

[Little Nunuu’s treasure hunt]

Helsinki: Lasten keskus, 2010. 32 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-627-829-5

€23.50, hardback

Petra Heikkilä (born 1976) is a visual artist and author. Her debut title, an illustrated children’s book entitled Mikko Kettusen pupupöksyt (‘Micky Fox’s bunny pants’, 2001), was nominated for the Finlandia Junior prize in 2001. Heikkilä’s practice of portraying children as animal characters is based on their facial expressions – particularly their luminous eyes. Typical features of all eight of her picture books published so far include a warm sense of humour, wordplay and the use of collage techniques in the illustrations. At the centre of this tale set in Africa is a kanga cloth, which can be twisted and wound in a variety of ways, and Nunuu, a little lion girl who learns about the inventive uses for kanga. The rich image textures utilise collage and photographs, as well as characters painted on Ugandan barkcloth.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

The bully

31 March 1996 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Tulen jano (‘Thirst for fire’, Gummerus, 1995); power relations between doctor and patient in a situation where the past will not leave either alone

Nurmikallio, an apparently ordinary middle-aged man, came back again and again, and it seemed as if there would be no end to his story.

I listened to him patiently at first. Repeatedly he returned to the same subject. The form and emphases of the story changed, new memories emerged, but the gist was the same: he had failed in his life and believed that the root cause of his failure was a particular person, a childhood class-mate, a bully.

On the basis of his first visit I wrote a short character-sketch:

Intellectually average. Talkative, but by his own account solitary. Difficulties in human relationships, separated, no children. Electrician by profession, says he likes his work. Biggest problem obsessive attachment to childhood traumas.

And that’s all, I thought. But he was not to be so easily dismissed.

The show must go on

30 June 2007 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Piru, kreivi, noita ja näyttelijä (‘The devil, the count, the witch and the actor’, Gummerus, 2007). Introduction by Anna-Leena Ekroos

‘I hereby humbly introduce the maiden Valpuri, who has graciously consented to join our troupe,’ Henrik said.

A slight girl thrust herself among us and smiled.

‘What can we do with a somebody like her in the group? A slovenly wench, as you see. She can hardly know what acting is,’ Anna-Margareta snapped angrily.

‘What is acting?’ Valpuri asked.

Henrik explained that acting was every kind of amusing trick done to make people enjoy themselves. I added that the purpose of theatre was to show how the world worked, to allow the audience to examine human lives as if in a mirror. Moreover, it taught the audience about civilised behavior, emotional life, and elegant speech. Ericus thought that the deepest essence of theatre was to give visible incarnation to thoughts and feelings. None of us understood what he meant by this, but we nodded enthusiastically. Anna-Margareta insisted that, say what you will, in the end acting was a childish game. Actors were being something they were not, just like children pretending to be little pigs or baby goats. More…

Living with a genius

23 June 2015 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s painting Symposium (1894). From left: Akseli Gallen-Kallela, the composer Oskar Merikanto, the conductor Robert Kajanus and Jean Sibelius. Aino Sibelius was not pleased with this depiction of her husband depicted during a drinking session with his buddies

It is 150 years since the birth of Finland’s ‘national’ composer, Jean Sibelius. Much has been written about his life; Jenni Kirves’s new book casts light on his wife, Aino (1871–1969), and through her on the composer’s emotional and family life.

Aino, Kirves remarks in her introduction, has often been viewed as an almost saintly muse who sacrificed her life for her husband. But she was flesh and blood, and the book charts the difficulties of life with her brilliant husband from the very beginning – his unfaithfulness during their engagement, how to deal with a sexually transmitted infection he had contracted, his alcohol problem, the death of a child. It was Aino’s choice, time and again, to stand by her man; she felt it was her privilege to support her husband in his work in every possible way. ‘For me it is as if we two are not alone in our union,’ she wrote, far-sightedly, as a young bride. ‘There is also an equally rightful third: music.’

Aino’s own family, the Järnefelts, were a considerable cultural force in Finland, supporters of Finnish-language education and the growing independence movement. Her brothers included the writer Arvid Järnefelt, the artist Erik Järnefelt and the composer Armas Järnefelt. It was Armas who introduced her to his friend Jean Sibelius.

Aino bore Sibelius – known in family circles as Janne – six daughters, and offered her husband her unfailing support through 65 years of married life. ‘I must have you,’ Sibelius wrote, ‘in order for my innermost being to be complete; without you I am nothing… For this reason you are as much an artist as I am – if not more.’

As an old lady, Aino remarked of her own life that it had been ‘like a long, sunny day.’

![]()

Aino Sibelius, 1891. Photo: National Board of Antiquities – Musketti.

An excerpt from Aino Sibelius: Ihmeellinen olento (‘Aino Sibelius: wondrous creature’, Johnny Kniga, 2015). We join the young couple in 1892 as they prepare for their long-awaited wedding.

At last, the wedding!

In the spring of 1892 the wedding really began to seem possible, as Janne’s symphonic poem Kullervo was very favourably received and Janne finally began to believe that he could support Aino. His financial situation was still, however, far from brilliant, and there were only two weeks to the wedding, as Janne wrote on 27 May 1892: ‘All the same, we must really be very careful about money. You will keep the cashbox and we will decide on everything together.’ The wedding grew closer and three days later Janne wrote triumphantly:

Do you understand, Aino, that we shall be man and wife in 1 ½ weeks – that we shall be able to kiss each other however we like and wherever we like (!) – and live together and have a household together – eat and make coffee together – it’s just so lovely.

A couple of weeks before the wedding, however, Janne wrote to Aino about some wishes for Aino in the future:

A skill with which a married artist can be protected from regressing is that the ‘wife’ understands to make him as little as possible into a model citizen. The man must not be allowed to be a paterfamilias with a pipe in his mouth, drowsy and docile; he must continually seek as many impressions as before, that’s clear, isn’t it? The kind of marriage whose main goal is the bringing of children into the world is repugnant to me – there are most certainly other things to do for those who work in the arts. More…

The Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2012

13 December 2012 | In the news

Ulla-Lena Lundberg. Photo: Cata Portin

The winner of the 29th Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2012, worth €30,000, is Ulla-Lena Lundberg for her novel Is (‘Ice’, Schildts & Söderströms), Finnish translation Jää (Teos & Schildts & Söderströms). The prize was awarded on 4 December.

The winning novel – set in a young priest’s family in the Åland archipelago – was selected by Tarja Halonen, President of Finland between 2000 and 2012, from a shortlist of six.

In her award speech she said that she had read Lundberg’s novel as ‘purely fictive’, and that it was only later that she had heard that it was based on the history of the writer’s own family; ‘I fell in love with the book as a book. Lundberg’s language is in some inexplicable way ageless. The book depicts the islanders’ lives in the years of post-war austerity. Pastor Petter Kummel is, I believe, almost the symbol of the age of the new peace, an optimist who believes in goodness, but who needs others to put his visions into practice, above all his wife Mona.’

Author and ethnologist Ulla-Lena Lundberg (born 1947) has since 1962 written novels, short stories, radio plays and non-fiction books: here you will find extracts from her Jägarens leende. Resor in hällkonstens rymd (‘Smile of the hunter. Travels in the space of rock art’, Söderströms, 2010). Among her novels is a trilogy (1989–1995) set in her native Åland islands, which lie midway between Finland and Sweden. Her books have been translated into five languages.

Appointed by the Finnish Book Foundation, the prize jury (researcher Janna Kantola, teacher of Finnish Riitta Kulmanen and film producer Lasse Saarinen) shortlisted the following novels: Maihinnousu (‘The landing’, Like) by Riikka Ala-Harja, Popula (Otava) by Pirjo Hassinen, Dora, Dora (Otava) by Heidi Köngäs, Nälkävuosi (‘The year of hunger’, Siltala) by Aki Ollikainen and Mr. Smith (WSOY) by Juha Seppälä.

The way to heaven

30 June 1996 | Archives online, Fiction

Extracts from the novel Pyhiesi yhteyteen (‘Numbered among your saints’, WSOY, 1995). Interview with Jari Tervo by Jari Tervo

The wind sighs. The sound comes about when a cloud drives through a tree. I hear birds, as a young girl I could identify the species from the song; now I can no longer see them properly, and hear only distant song. Whether sparrow, titmouse or lark. Exact names, too, tend to disappear. Sometimes, in the old people’s home, I find myself staring at my food, what it is served on, and can’t get the name into my head. The sun came to my grandson’s funeral. It rose from the grave into which my little Marzipan will be lowered. I don’t remember what the weather did when my husband was buried.

A plate. Food is served on a plate. There are deep plates and shallow plates; soups are ladled into the deep ones. More…

Success after success

9 March 2012 | This 'n' that

The women of Purge: Elena Leeve and Tea Ista in Sofi Oksanen's Puhdistus at the Finnish National Theatre, directed by Mika Myllyaho. Photo: Leena Klemelä, 2007

Sofi Oksanen’s Purge, an unparalleled Finnish literary sensation, is running in a production by Arcola Theatre in London, from 22 February to 24 March.

First premiered at the Finnish National Theatre in Helsinki in 2007, Puhdistus, to give it its Finnish title, was subsequently reworked by Oksanen (born 1977) into a novel – her third.

Puhdistus retells the story of her play about two Estonian women, moving through the past in flashbacks between 1939 and 1992. Aliide has experienced the horrors of the Stalin era and the deportation of Estonians to Siberia, but has to cope with the guilt of opportunism and even manslaughter. One night in 1992 she finds a young woman in the courtyard of her house; Zara has just escaped from the claws of members of the Russian mafia who held her as a sex slave. (Maya Jaggi reviewed the novel in London’s Guardian newspaper.) More…