Search results for "harjunpää/2010/10/mikko-rimminen-nenapaiva-nose-day"

The Hunter King

9 August 2012 | Fiction, Prose

A story from the collection of fiction and non-fiction, Salattuja voimia (‘Hidden powers’, Teos, 2012)

And just as Gran Paradiso is the highest peak in unified Italy, the only mountain whose rugged, perpetually snow-capped summit reaches a height of over thirteen thousand feet (there are rumours that, on a clear day, you can see the peaks of both Mont Blanc and the Matterhorn from the top), so we know that the largest and most splendid mountain creature throughout Europe is the ibex, which grazes on the slopes of Gran Paradiso – the ibex, the alpine goat, the distant ancestor and modern-day cousin of our own homely goat, the French bouquetin and the German Steinbock.

The male ibex can be the size of a foal, about three feet tall, and its curved horns, like Oriental daggers decorated with rippling patterns, can grow to reach the same length as the creature’s own height. Local folklore tells us that, in the olden days when the mists of the distant Ice Age still hung heavy in the gullies of Valle d’Aosta and Valle d’Orso, herds of ibexes could still be seen further down the mountain slopes, but because the ibex loves the cooling mountain winds and values the cold, which keeps predators from the valleys at bay, they moved up to the most inhospitable terrain and made it their home.

But there was one beast that followed the ibex up these paths, sowing fear and causing death and destruction – and that beast was man. More…

The enchanted garden

31 December 1993 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Säädyllinen murhenäytelmä (‘A respectable tragedy’, 1941). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

Artur sat on the balcony and contemplated the windowpanes, hot and bright as dragonfly’s wings. He reached into his pocket and produced an ivory cigarette-holder, inserted a fresh salt-capsule and a cigarette, and began smoking, but the cigarette was not to his taste. His mouth felt hot and dry; he probed the roof of his mouth with his tongue.

An ant was making its way across the floor; Artur’s gaze rested on the garden’s universe of flowerbeds, swarming with insects and blooms; the atmosphere in the garden had the tint of hot dust, apart from the lawn, with its limeblossom-tinged half light. He started to make for the garden: the flowers would all be needing water, and he could go for a swim in the pond. But first he wanted to take a look at his mother: she might manage an hour’s sleep in this heat. He tapped a drift of blue-grey cigaretteash onto the floor. He tiptoed heavily to the old lady’s door, making the floorboards creak, and opened it a fraction. In the green aqueous light thrown by the blind he could make out the reposing outlines of a weak, almost immaterial body; her throat and chest moved gently under her star-crocheted lace, but otherwise the old lady was sleeping lightly as a bird. More…

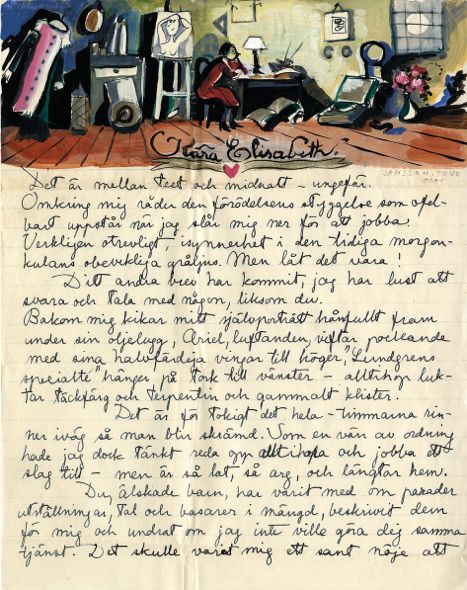

Letters from Tove

6 October 2014 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Early days: Tove Jansson went to Stockholm to study art when she was just 16. A letter to her friend Elisabeth Wolff, from November 1932

Artist and author Tove Jansson (1914–2001) is known abroad for her Moomin books for children and fiction for adults. A large selection of her letters – to family, friends and lovers – was published for the first time in September. In these extracts she writes to her best friend Eva Konikoff who moved to the US in 1941, to her lover, Atos Wirtanen, journalist and politician, and to her life companion of 45 years, artist Tuulikki Pietilä.

Brev från Tove Jansson (selected and commented by Boel Westin and Helen Svensson; Schildts & Söderströms, 2014; illustrations from the book) introduced by Pia Ingström

7.10.44. H:fors. [Helsinki]

exp. Tove Jansson. Ulrikaborgg. A Tornet. Helsingfors. Finland. Written in swedish.

to: Miss Eva Konikoff. Mr. Saletan. 70 Fifty Aveny. New York City. U.S.A.

Dearest Eva!

Now I can’t help writing to you again – the war [Finnish Continuation War, from 1941 to 19 September 1944] is over, and perhaps gradually it will be possible to send letters to America. Next year, maybe. But this letter will have to wait until then – even so, it will show that I was thinking of you. Curiously enough, Konikova, all these years you have been more alive for me than any of my other friends. I have talked to you, often. And your smiling Polyfoto has cheered me up and comforted me and has also taken part in the fortunate and wonderful things that have happened. I remembered your warmth, your vitality and your friendship and felt happy! At first I wrote frequently, every week – but after about a year most of it was returned to me. I wrote more after that, but the letters were often so gloomy that I didn’t feel like saving them. Now there are so absurdly many things I have to talk to you about that I don’t know where to begin. Koni, if only I’d had you here in my grand new studio and could have hugged you. After these recent years there is no human being I have longed for more than you. More…

Happy days, sad days

28 February 2013 | Reviews

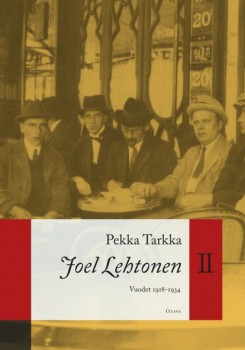

Pekka Tarkka

Pekka Tarkka

Joel Lehtonen II. Vuodet 1918–1934

[Joel Lehtonen II. The years 1918–1934]

Helsinki: Otava, 2012. 591 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-25924-4

€38.50, hardback

A well-meaning bookseller’s idealism, inspired by Tolstoyan ideology, is brought crashing down by the laziness and ingratitude of the man hired to look after his estate: conflicts between the bourgeoisie and the ‘ordinary folk’ are played out in heart of the Finnish lakeside summer idyll in Savo province.

Taking place within a single day, the novel Putkinotko (an invented, onomatopoetic place name: ‘Hogweed Hollow’) is one of the most important classics of Finnish literature. Putkinotko was also the title of a series (1917–1920) of three prose works – two novels and a collection of short stories – sharing many of the same characters [here, a translation of ‘A happy day’ from Kuolleet omenapuut, ‘Dead apple trees’, 1918] .

In 1905 Joel Lehtonen bought a farmstead in Savo which he named Putkinotko: it became the place of inspiration for his writing. With an output that is both extensive and somewhat uneven, the reputation of Joel Lehtonen (1881–1934) rests largely on the merits of his Putkinotko, written between 1917 and 1920. More…

A view to a kill

31 December 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Klassikko (‘The classic’, WSOY, 1997). Pete drives an old Toyota Corolla without a thought for the small animals that meet their death under its wheels – or anything else, for that matter. Hotakainen describes the inner life of this environmental hazard with accuracy and precision

Pete sat in his Toyota Corolla destroying the environment. He was not aware of this, but the lifestyle he represented endangered all living things. The car’s exhaust fumes spread into the surroundings, its aged engine sweated oil onto the pavement, and malodorous opinions withered the willowherbs by the roadside. Granted that Pete was an environmental hazard, one must nevertheless ask oneself: how many people does one like him provide with employment? He leaves behind him a trail of despondent girlfriends who require the services of human relations workers, popular songwriters, and social service officials; during his lifetime, he spends tens of thousands of marks in automotive shops and service stations, on spare parts and small cups of coffee; he benefits the food industry by being a carefree purchaser of TV dinners and soft drinks. Pete is the perfect consumer, an apolitical idiot who votes with his wallet, the favorite of every government, even though no one seems interested in putting him to work, least of all himself. Every government, regardless of political power struggles, encourages its people to consume. Pete needs no encouragement, he consumes unconsciously, and one might ask: is there anything that he does consciously, the Greens and left-wingers would like him to? Does Pete make smart long-range decisions? Hardly.

Bitter moments, luscious moments

31 March 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Fänrik Ståls sägner (Tales of Ensign Stål, 1848–1860) and Dikter II (‘Poems II’. 1833), translated by Judy Moffett. Introductions by Pertti Lassila and Risto Ahti

Sven Duva

Sven Duva’s sire a sergeant was, had served his country long,

Saw action back in ‘88, and then was far from young.

Now poor and gray, he farmed his croft and got his living in,

And had about him children nine, and last of these came Sven.

Now if the old man did, himself have wits enough to share

With such a large and lively swarm – to this I cannot swear;

But plainly no attempt was made to stint the elder ones,

For scarce a crumb remained to give this lastborn of his sons. More…

The guest book

30 June 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract rom the novel Kenen kuvasta kerrot (‘Whose picture are you talking about’, Otava, 1996). Introduction by Pia Ingström

Late at night before going to bed An Lee had turned off all the lights, opened the large bedroom window, breathed the cool air. She had done this often. It made it easier to fall asleep. It was enough to look outside for a moment and to breathe in slowly, and at the same time the bedroom air freshened and changed for the night.

Then she had closed and locked the window, drawn the curtains, and switched on the dim wall light. It might be nice to decorate the space between the double windowpanes with wooden animals, she had thought, not for the first time. They had had some at home, her mother had been a collector of such things. Almost all of them pink and lemon yellow, a whole zoo between the windows, only the panther had been pitch-black, and on one of the elephants the pretty grey color had been scratched and splotchy on one side. More…

Fight Club

16 April 2012 | Fiction, Prose

A short story from Himokone (‘Lust machine’, WSOY, 2012). Interview by Anna-Leena Ekroos

Karoliina wondered whether her name was suitable for a famous poet.

Her first name was alright – four syllables, and a bit old-fashioned. But Järvi didn’t inspire any passion. Should she change her name before her first collection came out? Was there still time? She had four months until September.

Even if The flower of my secret was the name of some old movie, Karoliina clung to the title she’d chosen. It described the book’s multifaceted, erotically-tinged sensory world and the essential place of nature in the poems. Karoliina loved to take long walks in the woods. Sometimes she talked to the trees.

She had been meeting new people. At the writer’s evening organised by her publisher, she’d been seated next to Märta Fagerlund, in the flesh. Karoliina had read Fagerlund’s poems since her teens, and seen her charisma light up the stage on cultural television shows.

At first Karoliina couldn’t get a word out of her mouth. She just blushed and dripped gravy on her lap. But the longer the evening went on, the more ordinary Märta seemed. She was even calling her Märta, and telling her about a new friend on Facebook who said how ‘awfully funny’ Märta was. In fact, the squeaky-voiced Märta, with her enthusiasm for Greece, was a bit dry, and, after three glasses of white wine, tedious. But Karoliina never mentioned it to anyone, because she wasn’t a spiteful person. More…

When I’m ninety-four

14 November 2013 | Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Kuolema Ehtoolehdossa (‘Death in Twilight Grove’, Teos, 2013). Minna Lindgren interviewed by Anna-Leena Ekroos

At the Health Clinic, Siiri Kettunen once more found a new ‘personal physician’ waiting for her. The doctor was so young that Siiri had to ask whether a little girl like her could be a real doctor at all, but that was a mistake. By the time she remembered that there had been a series of articles in the paper about fake doctors, the girl doctor had already taken offence.

‘Shall we get down to business?’ the unknown personal physician said, after a brief lecture. She told Siiri to take off her blouse, then listened to her lungs with an ice-cold stethoscope that almost stopped her heart, and wrote a referral to Meilahti hospital for urgent tests. Apparently the stethoscope was the gizmo that gave the doctor the same kind of certainty that the blood pressure cuff had given the nurse.

‘I can order an ambulance,’ the doctor said, but that was a bit much, in Siiri’s opinion, so she thanked her politely for listening to her lungs and promised to catch the very next tram to the heart exam. More…

Things

31 March 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short sory from Kaunis nimi (‘A lovely name’, Otava, 1996). Raija Siekkinen’s limpid prose is at its best when she explores the complex feelings that lie behind the events of everyday life. Here objects are indicators of emotions, memory and loss, and what is most important is left unsaid

And where was the pen, the fountain pen, black, chubby; the one which pumped the ink straight up from the bottle?

There were three gold-coloured bands on the cap of the pen, and its nib, too, was golden, It had been given to her in a case lined with black velvet, and there was a groove for the pen, and a depression for the ink-bottle; and the bottle was narrow -necked, with curving sides, and the ink in it was not bright blue, but dark, so that words written in it looked old, written a long time ago; one forgot that one had written them oneself, one read them like the words of a stranger.

She remembered the pen, and began slowly to wake up. More…

Nine lives

30 September 1994 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Entire lives flash by in half a page in this selection of very short short stories. Extracts from Elämiä (‘Lives’, Otava, 1994)

Silja

Silja was born in 1900. The home farm had been sub-divided many times. Silja threw a piece of bread on the floor. ‘Don’t sling God’s corn,’ said grandmother. Silja got up to go to school at four. In the cart, her head nodded; when the horse was going downhill its shoes struck sparks in the darkness. Silja’s brother drove to another province to go courting. Silja sat in the side-car. ‘The birches were in full leaf there,’ she said at home. Silja went to Helsinki University to read Swedish. She saw the famous Adolf Lindfors playing a miser on the big stage at the National Theatre. Silja got a senior teaching post at the high school. With a colleague, she travelled in Gotland. Silja donated her television set to the museum. It was one of the first Philips models. ‘Has this been watched at all?’ they asked Silja. Silja learned to drive after she retired. She called her car ‘The Knight’. The teachers’ society made a theatre trip to Tampere. Silja looked up her colleague in the telephone directory in the interval. There was no one of that name. More…

Lest your shadow fade

31 March 1987 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Jottei varjos haalistu (‘Lest your shadow fade’, 1987). Interview by Erkka Lehtola

‘… learn, then, to like yourself.

Dancing beside your shadow, laugh and play.

Dance always in the sunlight, lest your shadow fade.’J. Fr. Erlander, 1876 (Erika Kuovinoja’s grandfather)

‘Tis in life’s hardness that its splendour lies.’

J. Fr. E., 1890

Three days before the date fixed for the funeral, the minister directed his steps towards the home of the deceased, trying, as he walked, to compose his thoughts, which were full of righteous Lutheran anger. There were many good reasons for this. On the other hand, nothing that had happened in the past ought to make any difference, now that he was on his way to visit a house of mourning. A visit that called for the exercise of understanding, and even, if possible, kindness. It was a lot for anyone to expect, even of a clergyman. It was not by his own desire that he was paying this call: it was a matter of duty. And this time he was the protagonist. Petulantly, his shoes crunched the gravel. More…