Search results for "harjunpää/2010/10/mikko-rimminen-nenapaiva-nose-day"

Still alive

31 March 2000 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Maa ilman vettä (‘A world without water’, Tammi, 1999)

The window opened on to a sunny street. Nevertheless, there was a pungent, sickbed smell in the room. There were blue roses on a white background on the wallpaper and, on the long wall, three landscape watercolours of identical size: a sea-shore with cliffs, a mountain stream, mountaintops. The room was equipped with white furniture and a massive wooden table. The television had been lifted on to a stool so that it could be seen from the bed.

The bed had been shifted to the centre of the room with its head against the rose-wall, as in a hospital. Between white sheets, supported by a large pillow, Sofia Elena lay awake in a half-sitting position. More…

The life of a lonely friend

30 September 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Bo Carpelan. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

Extracts from Bo Carpelan‘s novel Axel, ‘a fictional memoir’ (1986). In his preface to the novel Bo explains how he ‘found’ Axel.

Preface

In the 1930s I came across the name of Axel Carpelan (1858-1919), my paternal grandfather’s brother, in Karl Ekman’s Jean Sibelius and His Work (1935). In the bibliography, the author briefly mentions quotes from letters in the book addressed to Axel Carpelan, ‘who belonged to the Master’s most intimate circle of friends, and in musical matters was his constant confidant. Sibelius commemorated their friendship by dedicating his second symphony to him’. I had never heard Axel’s name mentioned in my own family.

Many years after Karl Ekman, the original incentive for the novel about Axel arose through Erik Tawaststjerna’s biography of Sibelius, in which Axel is portrayed in the second volume (1967) of the Finnish edition, and whose life came to an end in Part IV (1978). From early 1970s onwards, I started notes for Axel’s fictional diary from to 1919. It is not known whether Axel himself ever kept a diary. I relied as muchas possible on all the available facts. These increased when I was given access to letters exchanged between Axel and Janne from the year 1900 onwards. It became the story of the hidden strength a very lonely and sick man, and of a friendship in which the give and take both sides was far greater than Axel himself could ever have imagined.

Hagalund, June 1st, 1985

Bo Carpelan

![]()

1878, Axel’s diary

15.1.

On my twentieth birthday, I remember the young Wolfgang; ‘Little Wolfgang has no time to write because he has nothing to do. He wanders up and down the room like a dog troubled by flies’. However, that dog achieved a paradise. I have learnt yet one more piece of wisdom: ‘It is my habit to treat people as I find them; that is the most rewarding in the long run’. More…

The Paradox Archive

30 September 1991 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Umbra (WSOY, 1990). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

The Paradox Archive

Umbra was a man of order. His profession alone made him that, for sickness was a disorder, and death chaos.

But life demands disorder, since it calls for energy, for warmth – which is disorder. Abnormal effort did perhaps enhance order within a small and carefully defined area, but it squandered considerable energy, and ultimately the disorder in the environment was only intensified.

Umbra saw that apparent order concealed latent chaos and collapse, but he knew too that apparent chaos contained its own order. More…

Meetingplace the year

30 June 1978 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Kohtaamispaikka vuosi (‘Meetingplace the year’, 1977). Introduction by Mirjam Polkunen

1.

I look in from the gateway

there are children, there in the yard playing.

They look small from here, remote.

From the years

I have walked past this gateway,

there they are: five, six.

The same number.

They have a ball in the air, they yell at it.

Silly that I still here too

remember you,

I could be the same age now.

More…

The height of the night

15 October 2009 | Letter from the Editors

The autumnal equinox is past; and as we tilt towards the winter solstice, here in these northerly latitudes, the darkness expands palpably from day to day, giving more space for introspection – high on the list of Finnish national pastimes – and for reading.

The autumnal equinox is past; and as we tilt towards the winter solstice, here in these northerly latitudes, the darkness expands palpably from day to day, giving more space for introspection – high on the list of Finnish national pastimes – and for reading.

We want to make our website primarily a place for reading – not, in other words, for clicking, going on to the next thing. To think to the end what cannot be thought to the end elsewhere, as the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam said of his experience of staying in what was, at the turn of the 20th century, still Finnish Karelia. So you will not find our texts littered with links; for the most part, links appear at the end of a piece, not in it. More…

Once upon a time

27 February 2014 | Children's books, Fiction

Stories from Kirahviäiti ja muita hölmöjä aikuisia (‘The giraffe mummy and other silly adults’, Teos, 2013), illustrated by Martina Matlovičová. Interview of Alexandra Salmela by Anna-Leena Ekroos

Stories from Kirahviäiti ja muita hölmöjä aikuisia (‘The giraffe mummy and other silly adults’, Teos, 2013), illustrated by Martina Matlovičová. Interview of Alexandra Salmela by Anna-Leena Ekroos

The monkey princess

Adalmiina’s life was not an easy one. Her parents decided to prepare her for her career as a princess when she was a little girl: when Adalmiina was three she was sent to ballet school, at four she started taking lute lessons and at five she went on a course in magic-mirror gazing.

When Adalmiina turned six, she received a giant suitcase full of princess clothes and shoes.

‘Put them on, darling, we want to see you in all your lovely beauty!’ her mother sparkled, waving a muslin veil.

‘I want to go to the jungle!’ Adalmiina demanded. ‘Without any clothes!’

‘Will we have to force you to dress in all your glory?’ her parents snapped.

‘You’ll have to catch me first!’ Adalmiina announced, running into the garden. More…

An end and a beginning

31 March 1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Det har aldrig hänt (‘It never happened’, 1977). Translated and introduced by W. Glyn Jones

There they are!

Over the ice they ride. The hoofs in rhythmical movement kick up the snow. The trail points north west. The sound of the hoofs is absorbed in the blue twilight of a March evening. The two horsemen push on, close together, passing one tiny island after another. Their eyes are fixed on a trail which has lain before them throughout the day. They are hunting like wolves. Yes, like wolves they are.

Or are they?

The twilight gives way to darkness and the black of night. The riders lean low over their horses in an attempt to follow the trail, but at last one of them raises his hand. The hunt is called off. The horses snort and toss their heads so their manes dance. Clouds of steam rise from them, enveloping the men as they dismount and lead their horses to an islet where the dark and deserted profile of a fisherman’s cabin can be glimpsed. Heaven knows who the hut belongs to, but it is a good thing that it is there with its walls and a roof, a shelter against the night. More…

Adam, Eve and vegetarianism

30 September 2006 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Short prose from En god Havanna. Besläktad (‘A good Havana. Kith and kin’, Söderströms, 2006). Introduction by Bror Rönnholm

Ode

My alter ego has relatives who have bad teeth and the names of Greek gods. They live in ramshackle houses in suburbs which the taxi drivers can’t find, dangerous ex-no man’s lands in a rapid metastasis into concrete. They are wild and threatened with extinction, they are Finland-Swedish working class. Disorganised, of course they’re disorganised, my alter ego’s relatives never organise themselves. They don’t form part of any community other than their own. They go to sea and they breed, they buy shuteye dolls in whore ports and return home in grand style, always at night, always one surprising night when no one is expecting them. The women raise a cry of joy, the children go leaping barefoot, and the dog, which is called Zeus-Håkan, is quite beside himself. There’s a party. There’s no school that day. At twilight the women travel to their jobs in key factories and warehouses. When they come home the party continues and in the outside toilet there are new pictures of new places. My alter ego’s relatives have dyed hair and prominent busts in tight-fitting silver nylon jumpers. They pay for my alter ego’s father’s education so he can become middle class. They are proud of him. When we go to visit them they dress up. They clap their hands and the nail varnish peels as they loudly, just a shade too loudly, shout OH, oh splendid, such fine guests! My alter ego’s father is grateful and confused. He has long ago paid it back, paid the money back, and now what’s left is only what cannot be repaid.

With the passage of the years my alter ego’s working-class relatives are disappearing from my alter ego’s life. I miss them. More…

Disintegration

31 December 1992 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Pythonin yö (‘Night of the python’, Gummerus, 1992). Introduction by Kaija Valkonen

I feel as if the disintegration has already started. I do not want it, I am not yet ready. And I do not want to discuss it with the doctors; I know that they would not understand, and the thing I am talking about has nothing to do with my state of health. It is not an illness; it is something more insidious. It occurs under the cover of health. It is a deception.

It is hard to say when it started, but whenever I try to remember, a certain day comes into my mind. It can hardly be the beginning, how could disintegration start with joy? But it was a day that contained many elements of dissolution: a strong wind, the ice breaking, quickly moving clouds. At one point I picked up an old tub in the corner of the shed, its hoops fell off and it collapsed, ringing. More…

Why translate?

28 January 2015 | Essays, Non-fiction

Down by the sea: Herbert Lomas in Aldeburgh. – Photo: Soila Lehtonen

‘People do not read translations to encourage minor literatures but to rediscover themselves in new imaginative adventures‚’ says the poet and translator Herbert Lomas in this essay on translation (first published in Books from Finland 1/1982). ‘Translation is a thankless activity,’ he concludes – and yet ‘you have the pleasure of writing without the agony of primary invention. It’s like reading, only more so. It’s like writing, only less so.’ And how do Finnish and English differ from each other, actually?

Any writer’s likely to feel – unless he’s a star, a celebrity, a very popular and different beast – that the writer is a necessary evil in the publisher’s world, but not very necessary. How much more, then, the translator from a ‘small’ country’s language.

Why do it? The pay’s absurd, you need the time for your own writing, it’s very hard to please people, and translation is, after all, the complacent argument goes, impossible. I’m convinced by all these arguments, and really I can’t afford to go on; but I don’t regret what I’ve done and, looking back, I can find two reasons for translating Finnish writing, one personal, the other cultural. More…

Emotional transgressions

31 December 1985 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Three extracts from the novel Harjunpää ja rakkauden lait (‘Harjunpaa and the laws of love’). Introduction by Risto Hannula

It was a few minutes to two, and Harjunpää was still awake, lying so close to Elisa that he could feel her warmth. He kept his eyes open, staring into the night through the crack between curtains. Once again the boiler of the central heating plant started up, and the smoke began to rise like a stiff column in the cold. Another fifteen minutes had passed, and morning was a quarter of an hour closer. He squeezed his eyes shut and tried to concentrate on Elisa’s breathing and the sleepy snuffling of the girls, but his thoughts still wouldn’t leave him in peace. Inexplicably, he felt there was something wrong, that the darkness exuded some kind of threat, that he’d left something undone or had made some kind of mistake.

He swung his feet onto the floor and got up as quietly as he could. But all his care was wasted, he should have known that.

‘What’s the matter?’ Elisa asked sleepily.

‘I just can’t get to sleep.’

‘Again … ‘

‘I can’t help it. I wonder if there’s a bottle of brew left.’

‘Sure. But listen …’

Pipsa turned over in her crib, rattling the sides, groped around a bit and began to suck her pacifier so you could hear the quiet sucking noises.

‘Yeah?’

‘Maybe you could see a doctor. You could ask for some mild … ‘ More…

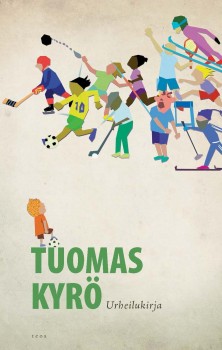

We are the champions

25 March 2011 | Prose

Heroes are still in demand, in sports at least. In his new book author Tuomas Kyrö examines the glorious past and the slightly less glorious present of Finnish sports – as well as the meaning of sports in the contemporary world where it is ‘indispensable for the preservation of nation states’. And he poses a knotty question: what is the difference, in the end, between sports and arts? Are they merely two forms of entertainment?

Heroes are still in demand, in sports at least. In his new book author Tuomas Kyrö examines the glorious past and the slightly less glorious present of Finnish sports – as well as the meaning of sports in the contemporary world where it is ‘indispensable for the preservation of nation states’. And he poses a knotty question: what is the difference, in the end, between sports and arts? Are they merely two forms of entertainment?

Extracts from Urheilukirja (‘The book about sports’, WSOY, 2011; see also Mielensäpahoittaja [‘Taking offence’])

The whole idea of Finland has been sold to us based on Hannes Kolehmainen ‘running Finland onto the world map’. [c. 1912–1922; four Olympic gold medals]. Our existence has been defined by how we are known abroad. Sport, [the Nobel Prize -winning author] F. E. Sillanpää, forestry, [Ms Universe] Armi Kuusela, [another runner] Lasse Viren, Nokia, [rock bands] HIM and Lordi, Martti Ahtisaari.

The purpose of sport at the grass-roots level has been to tend to the health of the nation and at a higher level to take our boys out into the world to beat all the other countries’ boys. We may not know how to talk, but our running endurance is all the better for it. However, the most important message was directed inwards, at our self image: we are the best even though we’re poor; we can endure more than the rest. Finnish success during the interwar period projected an image of a healthy, tenacious and competitive nation; political division meant division into good and bad, the right-minded and traitors to the fatherland. More…

Really existing?

30 March 2007 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Mehiläispaviljonki. Kertomus parvista (‘The Bee Pavilion. A story about swarms’, Teos, 2006)

There are few old buildings in this town. Most are demolished to make way for new ones long before they reach the end of their first century.

Nevertheless, one brick building in our part of town, built at the beginning of the last century, was spared demolition for a long time. The two-storey building functioned as a Support Centre for the Psychically Ill and later on, for a couple of winters, as a shelter for alcoholics. The board fence that had surrounded the building for decades was taken down long before the building itself, but the maples on the sidewalk cast their shadows on its windows to the very end. When the lilacs and dogwoods in the back garden were in bloom, their heavy racemes shed purple and white on the sand. More…

Conversations with a horse

31 December 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Kiinalainen puutarha (‘The Chinese garden’, Otava, 2004). Introduction by Anna-Leena Nissilä

Colonel Mannerheim.

Near Kök Rabat, on the caravan route between Kashgar and Yarkand.

October 1906

It is growing dark. Let the others go on ahead. Let us wait here awhile. Perhaps the pain will go over. We’ll get through.

Steady, Philip.

You always obey. And listen. Your ears proudly, handsomely pricked.

Steady, I said, there in the garden. No reaction. Everyone was moving. Pure comedy. And something else.

An illusion, two girls. Then gone.

How to explain.

Before that. I had a conversation with Macartney, the British chargé d’affaires…

Pain…. It burns, now it burns again. Let us wait now, Philip. Steady, steady now. More…