Search results for "harjunp/2010/10/mikko-rimminen-nenapaiva-nose-day"

My creator, my creation

A short story from En tunne sinua vierelläni (‘I don’t feel you beside me’, Teos, 2010)

Sticks his finger into me and adjusts something, tok-tok, fiddles with some tiny part inside me and gets me moving better – last evening I had apparently been shaking. Chuckles, gazes with water in his eyes. His own hands shake, because he can’t control his extremities. Discipline essential, both in oneself and in others.

What was it that was so strange about my shaking? He himself quivers over me, strokes my case and finally locks me, until the morning comes and I am on again, I make myself follow all day and filter everything into myself, in the evening I make myself close down and in the morning I’m found in bed again. Between evening and morning is a black space, unconsciousness, whamm – dark comes and clicks into light, light is good, keeps my black moment short. He has forbidden me it: for you there’s no night. Simply orders me to be in a continuum from morning to evening, evening to morning, again and again. But in the mornings I know I have been switched off. I won’t tell about it. Besides, why does exclude me from the night? I don’t ask, but I still call the darkness night. There is night and day, evening and morning will come. More…

Landscape

30 June 2006 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

(Landskap, 1919). Introduction by Juha Virkkunen

12 March

To begin with, there’s a great white field. The field is criss-crossed with low slender fences and little patches of yellow-green stubble peering up through the snow, and hare-tracks slanting away towards the stubble. But we won’t notice the fences and the stubble and the hare tracks. Because we’re going to take a wider, more sort of decorative view.

So we see the great white field. And where the field ends a dark green screen has been drawn. The screen has been cut short rather amusingly in the middle, so one can see yet another white held. This belongs to another village. And this other village itself has crept up timidly to the forest-clad hill and lies close to it, so we don’t notice this other village. Because we want to take a wider view of things. More…

Daddy dear

30 June 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Vanikan palat (‘Pieces of crispbread’, Otava, 2004). Interview by Soila Lehtonen

Dad’s at the mess again. Comes back some time in the early hours. Clattering, blubbing, clinging to some poem, he collapses in the hall.

We pretend to sleep. It’s not a bad idea to take a little nap. After a quarter of an hour Dad wakes up. Comes to drag us from our beds. Crushes us four sobbing boys against his chest as if he were afraid that a creeping foe intended to steal us. We cry too, of course, but from pain. Four boys belted around a non-commissioned officer is too much. It hurts. And the grip only tightens. Dad whines:

‘Boys, I will never leave you. Dad will never give his boys away. There will be no one who can take you from me.’ More…

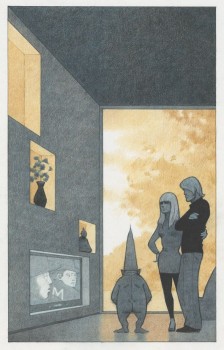

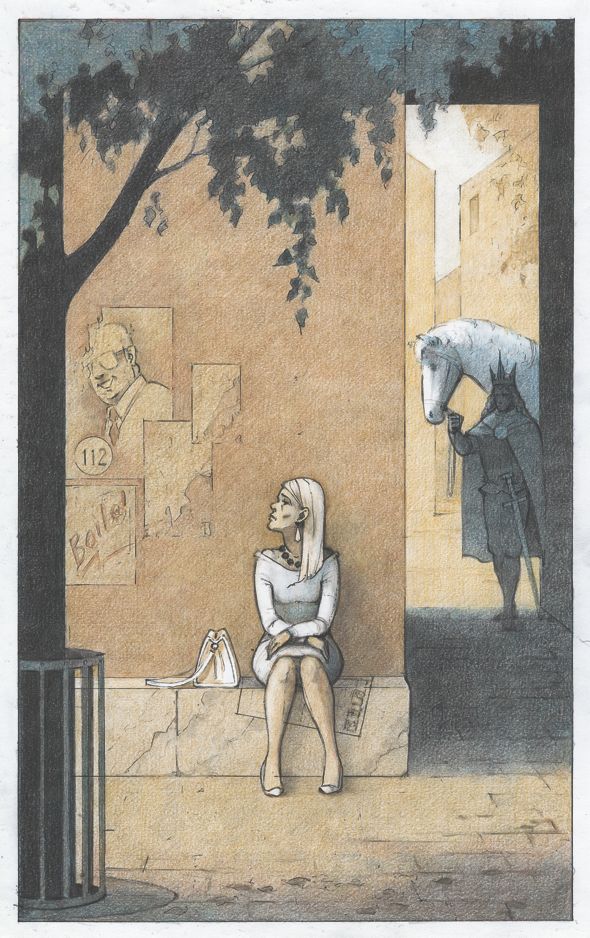

Picture this

Accompanied by one or two sentences of the most gnomic kind, architect Mikko Metsähonkala’s illustrations speak volumes. The picture-stories in his book Toisaalta / (P)å andra sidan / In Other Wor(l)ds blend the real and the surreal using fairy tales, references to historical or fictional characters and episodes from everyday life.

Accompanied by one or two sentences of the most gnomic kind, architect Mikko Metsähonkala’s illustrations speak volumes. The picture-stories in his book Toisaalta / (P)å andra sidan / In Other Wor(l)ds blend the real and the surreal using fairy tales, references to historical or fictional characters and episodes from everyday life.

(The Finnish composer Lauri Supponen was inspired by Metsähonkala’s ‘humaphone’ – see below –, and his composition The Dordrecht Humaphone was first performed at the Cheltenham Festival, England, in 2012, to favourable reviews.) More…

Coming up…

11 April 2013 | This 'n' that

Illustration: Mikko Metsähonkala

‘Just before the meeting Ludwig chickened out. In the ad he had bragged that he was a “sporty male with a sense of humour”. Would Patsy accept his illiteracy, brutal table manners and cruelty towards the peasants?’

One picture, few words: Mikko Metsähonkala’s artwork creates a moment in a universe – recognisable or completely strange – providing it with a laconic textual subtext. We feature some of his stories published in Toisaalta / (P)å andra sidan / In Other Wor(l)ds.

Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2010

19 November 2010 | In the news

A massive tome running to 1,000 pages by Vesa Sirén, journalist and music critic of the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper, features Finnish conductors from the 1880s to the present day. On 18 November it became the recipient of the 2010 Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction by the Finnish Book Foundation, worth €30,000.

A massive tome running to 1,000 pages by Vesa Sirén, journalist and music critic of the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper, features Finnish conductors from the 1880s to the present day. On 18 November it became the recipient of the 2010 Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction by the Finnish Book Foundation, worth €30,000.

The choice, from six shortlisted works, was made by economist Sinikka Salo. Suomalaiset kapellimestarit: Sibeliuksesta Saloseen, Kajanuksesta Franckiin (‘Finnish conductors: from Sibelius to Salonen, from Kajanus to Franck’) is published by Otava.

The other five works on the shortlist were Itämeren tulevaisuus (‘The future of the Baltic Sea’, Gaudeamus) by Saara Bäck, Markku Ollikainen, Erik Bonsdorff, Annukka Eriksson, Eeva-Liisa Hallanaro, Sakari Kuikka, Markku Viitasalo and Mari Walls; the Finnish Marshal C.G. Mannerheim’s early 20th-century travel diaries, Dagbok förd under min resa i Centralasien och Kina 1906–07–08 (‘Diary from my journey to Central Asia and China 1906–07–08’, Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland & Atlantis), edited by Harry Halén; Vihan ja rakkauden liekit. Kohtalona 1930-luvun Suomi (‘Flames of hatred and love. 1930s Finland as a destiny’, Otava) by Sirpa Kähkönen; Suomalaiset kalaherkut (‘Finnish fish delicacies’, Otava) by Tatu Lehtovaara (photographs by Jukka Heiskanen) and Puukon historia (‘A history of the Finnish puukko knife’, Apali) by Anssi Ruusuvuori.

European Union literature prizes 2010

8 October 2010 | In the news

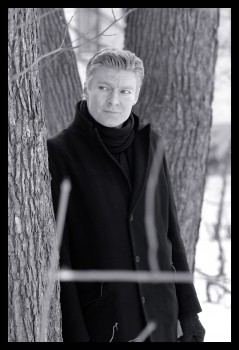

Riku Korhonen. Photo: Harri Pälviranta

With his novel Lääkäriromaani (‘Doctor novel’, Sammakko, 2009), Riku Korhonen (born 1972) is one of the 11 winners of the 2010 European Union Prize for Literature, worth €5,000 each. The winners were announced at Frankfurt Book Fair on 6 October.

The European Commission, the European Booksellers’ Federation (EBF), the European Writers’ Council (EWC) and the Federation of European Publishers (FEP) award the annual prize, which is supported through the European Union’s culture programme. It aims to draw attention to new talents and to promote the publication of their books in different countries, as well as celebrating European cultural diversity. Authors who have published two to four prose works during the last five years and whose work has been translated into two foreign languages at the most are eligible for the prize.

Korhonen has published two novels, a collection of short prose and a collection of poetry. Read translated extracts, published in Books from Finland in 2003, from his first novel, Kahden ja yhden yön tarinoita (‘Tales from two and one nights’, 2003) here. More…

Jarl Hellemann in memoriam 1920–2010

15 March 2010 | In the news

One of the grand old men of Finnish publishing, Jarl Hellemann, wrote in one of his own books: ‘Book publishing is by nature personified, a personal activity.

‘Most of the world’s old publishing houses still bear their founders’ names: Bonnier, Collins, Heinemann, Harper, Knopf, Bertelsmann, Werner Söderström, Gummerus. Americans ignorant of the exceptions to this rule among Finnish publishers still occasionally begin their letters, “Dear Mr Otava” or “Dear Mr Tammi”.’ (From Kustantajan näkökulma, ‘A publisher’s point of view’, Otava, published in Books from Finland 3/1999)

Hellemann himself was Mr Tammi for a long time; he started as a publishing editor at Tammi Publishing Company in 1945 and retired as managing director in 1982.

In 1955 he founded Keltainen kirjasto, the ‘Yellow Library’, an imprint of novels published since the First World War by prominent writers from all over the world. The first was Too Late the Phalarope by Alan Paton, the latest – published in 2009 – was The Disappeared by Kim Echlin. The series now contains more than 400 works, among them novels by 24 Nobel prize-winners.

Among the books in Keltainen kirjasto (list, in Finnish), Hellemann’s favourite was James Joyce’s Ulysses, translated by the poet and author Pentti Saarikoski in 1964. Hellemann continued choosing books for Keltainen kirjasto long after he retired.

Born in Copenhagen, Hellemann moved with his family to his mother’s home country, Finland, in the 1930s. Well-travelled and fluent in many languages, Hellemann himself published a novel (at the age of 25), three books on publishing and, in 1996, his memoirs.

Finlandia Junior Prize 2010

26 November 2010 | In the news

The Finlandia Junior Prize has gone to author Siri Kolu and illustrator Tuuli Juusela for the novel Me Rosvolat (‘Me and the Robbersons’, Otava); they will share the award of €30,000 (see the Prize jury assessments of the shortlist here). The winner was chosen by actor and writer Hannu-Pekka Björkman.

The Finlandia Junior Prize has gone to author Siri Kolu and illustrator Tuuli Juusela for the novel Me Rosvolat (‘Me and the Robbersons’, Otava); they will share the award of €30,000 (see the Prize jury assessments of the shortlist here). The winner was chosen by actor and writer Hannu-Pekka Björkman.

Awarding the prize on 25 November he said: ‘It caught my attention that in none of the six shortlisted children’s books are there any so-called nuclear families, at least not for long. The main characters constantly live and grow without something – the lack of parents or the attention of an adult is a serious matter to a child. However, in these books there is always someone who cares, not perhaps a stereotypical mom or dad, but an adult nevertheless.’ In Björkman’s opinion Me Rosvolat, with its rich language and a whiff of anarchy, presents the reader with moments of realisation and wonderment.

Snowbirds

2 November 2011 | Extracts, Non-fiction

The short winter days of the northerly latitudes are made brighter by snow cover, which almost doubles the amount of available light. Reflection from the snow is an aid for photographers working outdoors in winter conditions. A new book, entitled Linnut lumen valossa (‘Birds in the light of snow’), presents the best shots by four professionals, Arto Juvonen, Tomi Muukkonen, Jari Peltomäki and Markus Varesvuo, who specialise in patiently stalking the feathered survivors in the cold

The photographs and texts are from the book Linnut lumen valossa (‘Birds in the light of snow’, edited by Arno Rautavaara. Design and layout by Jukka Aalto/Armadillo Graphics. Tammi, 2011)

Snowy owl. Photo: Markus Varesvuo, 2010

Daddy’s girl

30 September 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Maskrosguden (‘The dandelion god’, Söderströms, 2004). Introduction by Maria Antas

The best cinema in town was in the main square. The other was a little way off. It was in the main square too, but you couldn’t compare it to the Royal. At the Grand there was hardly any room between the rows, the floor was flat and there was a dance-hall on the other side of the wall, so that Zorro rode out of time with waltzes, in time with oompahs, out of time with the slow steps of tangos and in time with quick numbers. The Royal was different and had a sloping floor.

Inside, the Royal was several hundred metres long. You could buy sweets on one side and tickets on the other. From Martina Wallin’s mum. She was refined. So was everyone except us: Mum, Dad and me. More…

Misery me

Extracts from the collection of short prose, Mielensäpahoittaja (‘Taking offense’, WSOY, 2010)

Past pushing up daisies

Well, yeah, so I took offense when the doctor said that considering my age I’m in tip-top shape. His theory was that my 25-kilometre ski circuits would keep an old coot like me in shape, if they didn’t kill me first. He said if I were to start just sitting on the couch and waiting, then the Reaper would be on my back in no time.

I don’t ski for my health. I ski because it’s pretty in the forest, and when a body is sweating he doesn’t think a whole lot. More…

A perfectly ordinary day

30 September 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extract from the novel Kello 4.17 (‘The time was 4.17’, WSOY, 1996). When time loses its meaning, real fear strikes like an iron glove. Aho writes about a man who is different but no outcast

I was lost to myself, if it is possible to be lost if you haven’t gone anywhere. Black birds curved through my mind and it felt as if no one needed me, no one or nothing: my mother bought clothes and make-up and did not seem to care; Uncle Lasse looked after the family business, steam coming out of his head, and kept shopkeepers and shopaholic customers happy; smiling bank managers slapped shy loan applicants encouragingly on the back, the gross national product grew without me having anything to do with it, or because I didn’t; and politics plodded onward as the mud squelched comfortingly. The machine of society hummed and ticked and Finland was as round and fat as a bomb. I looked at it and nothing changed, and on Sundays it was so quiet that you could look out of the window and see the Sahara.

A roof with a view

27 August 2009 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Mistä on mustat tytöt tehty? (‘What are black girls made of?’, Tammi, 2009) Introduction by Tuomas Juntunen

I’m a chimney sweep’s daughter, born October 1962 as a gift, a light to a darkened world. I’ve had lots of mothers, but none of them ever stuck around for good. One of them gave birth to me, so she’s Mother, not mother. Her name is Dewdrop, because water has spilled over the only photograph of My Mother and now her face has dissolved into a single translucent droplet; her nose, cheeks and chin are now a fat, shiny blob that looks like it’s about to fall out of the bottom of the picture. More…