Search results for "herbert lomas/www.booksfromfinland.fi/2004/09/no-need-to-go-anywhere"

Secret lives

30 September 2002 | Fiction, Prose

From Piiloutujan maa (‘The land of the hider’, Otava, 2002)

When we look for a good apartment, a good café, a good place to be, we are looking for a childhood hideaway. We are looking for the wardrobe we used to retreat into when we had been hurt. We will always remember what being there feels like. We yearn for that same illumination, felt by the baby Jesus in Mary’s womb, as the world’s light shone in through the hymen. More…

Alone here

31 March 1989 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Gösta Ågren has published a couple of dozen volumes of poetry; Jär (the title is a dialect word meaning ‘here’) won the Finlandia Prize in 1989. Ågren’s earlier poems have been epic, tinged with Marxism, in the style of Whitman and Neruda. Gradually his has become more strongly linguistically concentrated, developed towards a more conventionally lyrical style questioning the problem of existence. He himself has expressed the matter in one of the paradoxical statements he particularly enjoys: ‘don’t worry / it will never work out.’ Introduction by Erkka Lehtola

Here

Here she came, through the motion

less Sunday of old age.

In headscarf and long skirt

she came, a tall bird

of clothes. She wondered in

the sunlight on the shed-hill

what she should do

so she could die. I must

write about this. For it happens

everywhere, and there are no

questions to answer. But questioning

is already insight. Only

those questions that are never asked

need answers. I remember

that her hands were no longer

part of her. Idle

they lay in her lap. She saw

with her eyes only darkness

and light. It was silent. I

thought: the silence is creeping

through her body. Soon

it will reach her heart. Soon

I will be alone

here. More…

The Confirmation Present

30 June 1980 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An excerpt from Rakas rouva K (‘Dear Mrs K.’, 1979). Introduction and interview by Auli Viikari

Lahtinen read through what he had written so far, and it pleased him, especially the quotation from Clausewitz. “It could be said,” he went on, “that the victories of the French Revolution during those two decades were due in most cases to the mistaken policies of its opponents, even though the actual coup that shook the world took place within the framework of war.” His article was about the British attitude to Germany’s expansionist policies. There would not be another Munich, he felt sure: the House of Commons had cheered Chamberlain for the last time. Where, he asked himself, would England eventually abandon the role of passive onlooker? At Danzig, surely. It would not be like Poland to give something for nothing. She would set a world war in motion, of that he had no doubt. And he could see Poland dissolving into ruin before his very eyes. More…

Baby-boxes

18 February 2015 | This 'n' that

Contents of the Finnish baby-box. Photo: Annika Söderblom © Kela

Shortly before my first baby was born – ah, all of thirteen years ago, and a bit more – I paid a visit to the baby department of a central London department store.

Surrounded by push-chairs, feeding pillows, milk-expressers, nappy bins, nappy sacks, pink baby-grows, blue baby-grows, and advice books of every persuasion, I felt bewildered. The choice seemed infinite. Surely it couldn’t be this complicated.

I picked up one of the books. ‘6:30 Get up with your baby.’ I don’t think so, I objected inwardly. I’ve never been an early bird. ‘7:30 Breakfast: toast and marmalade.’ Definitely not. No one was going to tell me what to eat, or when. Were they? What on earth was this brave new world of motherhood going to be like? More…

True or false?

An extract from the novel Toiset kengät (‘The other shoes’, Otava, 2007). Interview by Soila Lehtonen

‘What is Little Red Riding Hood’s basket like? And what is in it? You should conjure the basket up before you this very moment! If it will not come – that is, if the basket does not immediately give rise to images in your minds – let it be. Impressions or images should appear immediately, instinctively, without effort. So: Little Red Riding Hood’s basket. Who will start?’

Our psychology teacher, Sanni Karjanen, stood in the middle of the classroom between two rows of desks. Everyone knew she was a strict Laestadian. It was strange how much energy she devoted to the external, in other words clothes. God’s slightly unsuccessful creation, a plump figure with pockmarks, was only partially concealed by the large flower prints of her dresses, her complicatedly arranged scarves and collars. Her style was florid baroque and did not seem ideally suited to someone who had foresworn charm. Her hair was combed in the contemporary style, her thin hair backcombed into an eccentric mountain on top of her head and sprayed so that it could not be toppled even by the sinful wind that often blew from Toppila to Tuira. More…

Cautionary tales

30 September 2002 | Fiction, Prose

Short stories from Förklädnader. Sagor, parabler (‘Disguises. Stories, allegories’, Schildts, 2001; Valepukuja. Satuja, vertauksia, WSOY, 2002)

Assistance

All over Hellas, even in the barbarian lands, the lyre-players competed with one another. Odes, paeans, dithyrambs echoed endlessly. Phoebus Apollo himself generously oversaw these productions.

A certain promising singer, Deinarchos by name, who hoped to participate in the upcoming Pythian contest, sat in his study-cave in the mountains of Thessaly waiting for inspiration. He prayed repeatedly to Phoebus for help, but did not detect any response. More…

Digital dreams

4 February 2009 | Essays, Non-fiction

In this specially commissioned article, the first for the new Books from Finland website, Leena Krohn contemplates the internet and the invisible limits of literature.

Leena Krohn on the way to Cape Tainaron, Southern Peloponnese, Greece; this is where Europe ends. Her novel entitled Tainaron appeared in 1985. – Photo: Mikael Böök (2008)

The world wide web, whose services most of us now use for work or entertainment, is a greater invention than we have, perhaps, realised up till now: according to the writer Leena Krohn, it is nothing less than an evolutionary leap

Technology combats the limitations of our senses, geography, and time. The human eye can’t compete with the visual acuity of an eagle, or even a cat, but with the best telescopes it can see into the early history of the universe, with new electron microscopes it can distinguish individual atoms.

The human senses nevertheless have an unbelievably broad bandwidth. About a million times more data flows to our brains by means of our senses than we could ever grasp consciously. More…

Higher goals

31 December 1987 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Tammerkosken sillalla (‘On Tammerkoski bridge’, 1982). Introduction by Panu Rajala

I had thought there were a lot of books in the libraries in Oulu. But both those libraries were totally overshadowed when, having climbed up to the top of the Messukylä Workers’ House, I began to cast my eyes along the bookshelves in the attic. A tallish and refined-looking librarian responded when I exclaimed aloud.

‘Just under seven thousand volumes altogether. Some of them are out on loan. We’d like to have a lot more books, but getting the money to buy them is like getting water from a stone.’

‘But you’ve already got an incredible amount compared to what we have in the rural library at home… In Taivalkoski during the war all we had was two cupboardsful.’

‘You didn’t have a lot of choice there,’ agreed the librarian. More…

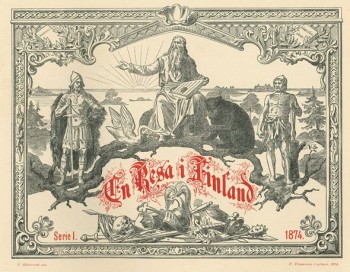

Becoming Finland

23 May 2013 | Reviews

Imaginary heroes: the title page of En resa i Finland. Illustration by C.E. Sjöstrand (1828–1906)

Zacharias Topelius

En resa i Finland

[A journey in Finland (1873)]

Helsinki: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 2013. 173 p., ill.

Utgivare [Editor]: Katarina Pihlflyckt

ISBN 978-951-583-260-3

€38, hardback

(Stockholm: Atlantis förlag, 2013. ISBN 978-91-7353-616-5)

The birth of Finland as a country came as a surprise to those who lived there.

It was created by Napoleon and Alexander I, becoming a reality following Russia’s victory over Sweden in the so called Finnish War. In 1809 Alexander exalted Finland as ‘a nation among nations’, however the new nation still needed to feel like a nation. The Russian rulers supported gentle and non-political nationalism in Finland, in the hope that it would mentally distance the country from Sweden. In this tranquillity, the sense of community they had envisioned grew in Finland.

For this, there were three key factors, all of which stemmed from the 1830s. Elias Lönnrot published the Kalevala, the national epic, proving that Finnish mythology and culture did indeed exist. The poet J.L. Runeberg (who would later become known as the national poet) gave Finland an appearance that was an ideology. He depicted a poor, pious and simple people, a harsh and beautiful wilderness, and with his poems he described the Finnish War, that Finland had lost, as a heroic battle of the people, fought for Finnish values. More…

Green thoughts

Extracts from the novel Kuperat ja koverat (‘Convex and concave’, Otava, 2010)

I decided to go to the Museum of Fine Arts.

After paying for my entrance ticket, I climbed the wide staircase to the first floor. There all I saw were dull paintings, the same heroic seed-sowers and floor-sanders as everywhere else. Why were so many art museums nothing more than collections of frames? Always national heroes making their horses dance, mud-coloured grumblers and overblown historical scenes. There was not a single museum in which a grandfather would not be sitting on a wobbly stool peering over his broken spectacles, interrogating a young man about to set off on his travels, cheeks burning with enthusiasm, behind them the entire village, complete with ear trumpets and balls of wool. The painting’s eternal title would be ‘Interrogation’ and it would be covered with shiny varnish, so that in the end all you would be able to see would be your own face.

I climbed up to the next floor. All I really felt was a pressing need to run away. No Flemish conversation piece acquired in the Habsburg era was able to erase a growing anxiety related to love. More…

The three-minute redemption

28 March 2013 | Fiction, Prose

Artist and writer Hannu Väisänen’s alter ego, Antero – who has appeared in Väisänen’s earlier autobiographical novels – is a young artist in his new novel Taivaanvartijat (‘The guardians of heaven’, Otava, 2013). Antero is invited to create the altarpiece for a new church. He rejects conventional, ecclesiastical ‘Sunday art’ and uses simple and versatile everyday symbols; his design contains an ordinary Finnish door key, familiar to everybody. The clergymen and laywomen are appalled: is this art, is it appropriate? In this extract the frustrated Antero takes a therapeutic break – on a roller-coaster

Now I need to get another beat into my head. What can help me forget those morose, curled up creatures, their strange commands and scents? I remember the roller-coaster. And I remember the ancient lore that it’s good to ride the roller-coaster with a lover before you attempt anything else. I go home quickly, throw down my sketch-book and my unnecessarily businesslike briefcase, exchange my suit, which was supposed to indicate devotion, for a windcheater, arrange my hair more carelessly, get on my bike and cycle to the funfair where I know the roller-coaster, the genuine, real, old-fashioned, clanking roller-coaster, to be.

Who could have been the first person to imagine the delights of the roller-coaster? Into whose happy capacity for daydreaming did it fall? Who saw those massive iron tentacles in their figure-eight shapes, those stretched and knotted rings of eternal joy? Who understood that on such a ride shame and anxiety would fall out of one’s pockets? It’s claimed that the first roller-coaster was invented by Catherine the Great. The monarch, with her multifarious patronage of culture, commissioned in Oranienbaum, St Petersburg, the first Montagne Russe amid the amusements of the wise: a Russian mountain with its ice-paths, raised into the air, which melted with the coming of spring. Who else could understand this organ-stirring amusement as deeply as the Great Wife with her hundreds of lovers. In the grip of mortal fear, I too always pray: before I am laid in earth, before the crematorium’s oven, take me once more to the roller-coaster. More…

The show must go on

30 June 2007 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Piru, kreivi, noita ja näyttelijä (‘The devil, the count, the witch and the actor’, Gummerus, 2007). Introduction by Anna-Leena Ekroos

‘I hereby humbly introduce the maiden Valpuri, who has graciously consented to join our troupe,’ Henrik said.

A slight girl thrust herself among us and smiled.

‘What can we do with a somebody like her in the group? A slovenly wench, as you see. She can hardly know what acting is,’ Anna-Margareta snapped angrily.

‘What is acting?’ Valpuri asked.

Henrik explained that acting was every kind of amusing trick done to make people enjoy themselves. I added that the purpose of theatre was to show how the world worked, to allow the audience to examine human lives as if in a mirror. Moreover, it taught the audience about civilised behavior, emotional life, and elegant speech. Ericus thought that the deepest essence of theatre was to give visible incarnation to thoughts and feelings. None of us understood what he meant by this, but we nodded enthusiastically. Anna-Margareta insisted that, say what you will, in the end acting was a childish game. Actors were being something they were not, just like children pretending to be little pigs or baby goats. More…