Search results for "herbert lomas/www.booksfromfinland.fi/2004/09/no-need-to-go-anywhere"

Shards from the empire

5 February 2010 | Fiction, Prose

‘Imperiets skärvor’, ‘Shards from the empire’, is from the collection of short stories, Lindanserskan (‘The tightrope-walker’, Söderströms, 2009; Finnish translation Nuorallatanssija, Gummerus, 2009)

Gustav’s greatest passion is for genealogy. He dedicates his free time to sketching coats of arms; masses of colourful, noble crests.

Gustav asked me to do a translation. I sat for ten days trying to decipher a couple of pages from a Russian archive dating from the 1830s. Sentences like, With this letter, we hereby give notice of our gracious decision.‘

The intricate handwriting belonged to some collegiate registrar or other. Perhaps Gogol’s Khlestakov. More…

Words like songs

The Finnish poet Helvi Juvonen (1919–1959) often studies small things: moles, lichen, bees and dwarf trees; she ‘doesn’t often dare to look at the clouds’. But small is beautiful; her nature poems and fairy-tales mix humility and the celebration of life. Commentary by Emily Jeremiah

Cup lichen

Luke 17:21

The lichen raised its fragile cup,

and rain filled it, and in the drop

the sky glittered, holding back the wind.

The lichen raised its fragile cup:

Now let’s toast the richness of our lives.

From Pohjajäätä [‘Ground-ice’], 1952) More…

Decisions, decisions: the fate of virtual literature

28 November 2013 | Articles, Non-fiction

Once upon a time: ‘Boyhood of Raleigh’ by J.E. Millais (1871). Wikipedia

In an era of ‘liveblogging’‚ we are all storytellers. But what’s the story, asks Teemu Manninen

One score of years ago, when the internet was new, the cultural critics of the time were fond saying that it would usher in a new utopia of free distribution of information: we would be able to read everything, know everything and share everything anywhere and every day.

Truly, they told us, we would become enriched by the internet to the point of not knowing what to do with all that wealth of knowledge, the amount of connections between us and the ever-increasing online availability of anyone with everyone, every waking hour.

Now that we really do have this always-on connectivity, you will indeed be available every waking hour: you will update your status, check your inbox, post pics and be available for chatting, texting, a quick email and a message or two, just to make sure no one is offended by your unreachability, since – from experience – a week’s worth of not tweeting or facebooking can make someone think that something serious has happened, or that you don’t even exist anymore. More…

Temporarily out of order

Extracts from the novel Hullu (‘The lunatic’, Teos, 2012). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

I found myself standing in front of the noticeboard. The rules were on a sheet of paper:

Ward 15 5-C

MEAL TIMES:

Breakfast 8:00 AM

Lunch 11:45 AM

Dinner 4:30 PM

Evening Snack 7:30 PM

COFFEE:

After lunch

We recommend leaving money, valuables, and bankbooks for storage in the ward valuables locker. We take no responsibility for items not left in the locker! Money may be retrieved 1–3 times per day. Use of mobile phones on the ward by arrangement.

VISITING HOURS:

M–F 2–7 PM

Sa–Su 12–7 PM

PERSONAL CLOTHING:

Use of one’s own clothing by individual arrangement. Clothing care individual. Washer and dryer available for use in the evenings after 6 PM.

OUTDOOR RECREATION:

Arranged individually according to health condition. Outdoor pass does not include the right to leave the area.

VACATIONS:

Vacations arranged during morning report, according to health condition.

NOTA BENE!

Smoking is only allowed on the smoking balcony! Smoking prohibited from 11 PM to 6 AM.

Pastor Karvonen available by appointment.

These were impossibly difficult rules. I read them through three times and simply did not understand. ‘Clothing care individual.’ ‘Outdoor pass does not include the right to leave the area.’

What did these sentences mean? With whom did you schedule the pastor and how? And why? More…

The guest book

30 June 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract rom the novel Kenen kuvasta kerrot (‘Whose picture are you talking about’, Otava, 1996). Introduction by Pia Ingström

Late at night before going to bed An Lee had turned off all the lights, opened the large bedroom window, breathed the cool air. She had done this often. It made it easier to fall asleep. It was enough to look outside for a moment and to breathe in slowly, and at the same time the bedroom air freshened and changed for the night.

Then she had closed and locked the window, drawn the curtains, and switched on the dim wall light. It might be nice to decorate the space between the double windowpanes with wooden animals, she had thought, not for the first time. They had had some at home, her mother had been a collector of such things. Almost all of them pink and lemon yellow, a whole zoo between the windows, only the panther had been pitch-black, and on one of the elephants the pretty grey color had been scratched and splotchy on one side. More…

Turd i’ your teeth

24 November 2011 | This 'n' that

Swearwords: universal language? Picture: Wikimedia

The title is a phrase by Shakespeare’s contemporary Ben Jonson, used in his plays.

In Japanese, swearwords are unknown. The worst thing you can say to a member of the African Xoxa tribe is ‘hlebeshako’, which roughly translates as ‘your mother’s ears’. ‘Swearing involves one or more of the following: filth, the forbidden and the sacred,’ says the American-born journalist and author Bill Bryson in his book Mother Tongue. The Story of the English Language (1990). It is a very entertaining and enlightening work full of interesting facts and peculiarities, many of them about a languages other than English.

There is one faulty reference to the Finnish language, though, and we do wonder how it has got into the book:

‘The Finns, lacking the sort of words you need to describe your feelings when you stub your toe getting up to answer a wrong number at 2.00 a.m., rather oddly adopted the word ravintolassa. It means “in the restaurant”.’ (p. 210)

Indeed it does, and definitely we never did. Adopt, that is. We’ve never ever heard anyone substituting a solid swearword – and there is no lack of sustainable, onomatopoeically effective (lots of r’s) examples in the Finnish language – for ‘ravintolassa’. Darn! Any Finn (prone to cursing) would say PERRRKELE, for example.

Someone, we fear, has been having Mr Bryson on.

You may say I’m a dreamer

25 November 2014 | Fiction, poetry

Prose poems from Tärnornas station – en drömbok (‘The Lucia Maids’ Station – a dream book’‚ Ellips, 2014). Introduction by Michel Ekman

I nurse a very small, perfectly formed child. It’s a girl. She smiles openly at me, even though she is so small. There is no doubt, neither about that nor anything else. The girl is the size of a nib pen, and just as exclusive. The nursing is going very well, it doesn’t hurt, and she can suckle without any problems. We are both at ease and yet awake, not introspective. The girl has intelligent eyes.

The milk keeps flowing.

Nothing runs dry.

Everything is obvious and neither of us is surprised. Just the fact that she is so small. Like a fountain pen. She is swathed in strips of bird cherry white bandages – like the ones mum had in her summer medicine cabinet – a cocoon, a chrysalis, but she’s not cramped, just secure. It smells good around us. I nurse my daughter who is perfect and the right size.

![]()

Heartstone

2 December 2010 | Reviews

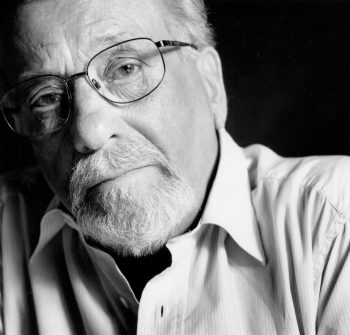

Ulla-Lena Lundberg

‘Knowledge enhances feeling’ is a motto that runs through the whole of Ulla-Lena Lundberg’s oeuvre – both her novels and her travel-writing, covering Åland, Siberia and Africa.

In her trilogy of maritime novels (Leo, Stora världen [‘The wide world’], Allt man kan önska sig [‘All you could wish for’], 1989–1995) she used the form of a family chronicle to depict the development of sea-faring on Åland over the course of a century or so. She gathered her material with historical and anthropological methodology and love of detail. The result was entirely a work of quality fiction, from the consciously old-fashioned rural realism of the first volume to the contradictory postmodern multiplicity of voices in the last – all of it in harmony with the times being depicted.

When Lundberg (born 1947) takes us underground or up onto cliff-faces in her new documentary book, Jägarens leende. Resor i hällkonstens rymd (‘Smile of the hunter. Travels in the space of rock art’), in order to consider cave- and rock-paintings in various parts of the world, she also reveals a little of the background to this attitude towards life that takes such delight in acquiring knowledge – an attitude that is familiar from many of the protagonists of her novels. More…

The summer of 1965

30 June 1995 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Underbara kvinnor vid vatten (‘Wonderful Women by the Sea’, Söderströms, 1994; Finnish translation lhanat naiset rannalla, Otava, 1995). Introduction by Michel Ekman

The summer of 1965; this summer people go waterskiing. They go waterskiing behind the Lindberghs’ shining mahogany sportsboat, and from midsummer onwards they go water-skiing behind Gabbe’s outboard motorboat, an Evinrude bought second-hand from Robin Lindbergh. Now Bella and Rosa are skiing: Tupsu Lindbergh’s face is covered in freckles if you look at her close to, and it’s not particularly becoming, her fair hair is super-peroxided and she is as thin as a skeleton and everyone knows that it’s because she is so thin and ugly and not because she has a cold that she says she can’t take part in any watersports. There is something nervous about Tupsu Lindbergh. At Bella’s party at the beginning of the summer Tupsu Lindbergh sits on the white villa’s veranda, on the white villa’s lawn on a camping chair, on the white villa’s beach while Bella and Rosa go waterskiing and talk about Tupperware. Not Tupperware all the time, but Tupperware is the collective description. More…