Search results for "herbert lomas/www.booksfromfinland.fi/2004/09/no-need-to-go-anywhere"

Winner of the Susan Sontag Prize

25 December 2010 | In the news

The Susan Sontag Foundation was established in New York in 2004 in memory of the celebrated author and cultural journalist Susan Sontag (1933–2004). The Foundation grants a prize to a young American who translates from other languages into English. In 2010 the prize was awarded for the third time.

Benjamin Mier-Cruz is currently pursuing his PhD in Scandinavian Languages and Literatures at University College Berkeley, with a particular interest in Finland-Swedish modernism and German expressionist poetry. His winning translation proposal is entitled Modernist Missives of Elmer Diktonius – Letters and Poetry of Elmer Diktonius.

Elmer Diktonius (1896–1961) was a rebellious Finland-Swedish avant-garde poet and composer, who was fluent in Finnish as well as his native Swedish. His letters to a wide range of European authors and critics, written between 1919 (the year of the Finnish Civil War) and 1951, reflect the political, artistic and personal developments in Finland and Europe.

The prize ceremony took place first in Helsinki on 5 November in a seminar at the Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland (the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland), then at Scandinavia House, New York, on 12 November.

When sleeping dogs wake

31 December 1994 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts rom the novel Tuomari Müller, hieno mies (‘Judge Müller, a fine man’, WSOY, 1994). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

In due course the door to the flat was opened, and a stoutish, quiet-looking woman admitted the three men, showed them where to hang their coats, indicated an open door straight ahead of them, and herself disappeared through another door.

After briefly elbowing each other in front of the mirror, the visitors took a deep breath and entered the room. The gardener was the last to go in. The home help, or whatever she was, brought in a pot of coffee and placed it on a tray, on which cups had already been set out, within reach of her mistress. The widow herself remained seated. They shook hands with her in tum. The mayor was greeted with a smile, but the bank manager and the gardener were not expected, and their presence came as a shock. She pulled herself together and invited the gentlemen to seat themselves, side by side, facing her across the table. They heard the front door slam shut: presumably the home help had gone out. More…

The honey of the bee

30 June 2005 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from the collection Mitä sähkö on (‘What electricity is’ WSOY, 2004). Introduction by Jarmo Papinniemi

Five days before I was born my grandfather reached sixty-six. He’d always been old. The first image I have of him gleams like a knife on sunny spring-time snow: he was pulling me on my sledge over hard frost under a bright glaring-blue sky. In the Winter War a squadron of bombers had flown through the same blue sky on their way to Vaasa; the boys leapt into the ditches for cover, as if the enemy planes could be bothered to waste their bombs on a couple of kids. Be bothered? Wrong: kids were always the most important targets.

Now it’s summer, August, and I’m sitting on the grassy, mossy face of the earth, which is slowly warming in a sun that’s accumulated a leaden shadiness. I’m sitting on my grandfather’s land. It’s the time when the drying machines buzz. Even with eyes shut, you can sense the corn dust glittering in the sun. Even with eyes shut, you can take in the smell of the barn’s old wood, the sticky fragrance of the blackcurrants barrelled on its floor, the tins of coffee and the china dishes on the shelves, and the empty grain bins; there’s the cupboard Kalle made, with its board sides and veneered door, and the dust-covered trunk that was going to accompany my grandfather to another continent. The ticket was already hooked, but Grandfather’s world remained here for good. When Easter comes we’ll gather the useless junk out into the yard and burn it; Grandfather’s travel chest will rise skywards. Grandfather stands in the barn entrance, leaning on the doorpost. He’s dead. Over all lies a heavy overbearing sun. Beyond the field the river’s flowing silently in its deep channel. At night time its dark and warm. More…

Conversations with a horse

31 December 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Kiinalainen puutarha (‘The Chinese garden’, Otava, 2004). Introduction by Anna-Leena Nissilä

Colonel Mannerheim.

Near Kök Rabat, on the caravan route between Kashgar and Yarkand.

October 1906

It is growing dark. Let the others go on ahead. Let us wait here awhile. Perhaps the pain will go over. We’ll get through.

Steady, Philip.

You always obey. And listen. Your ears proudly, handsomely pricked.

Steady, I said, there in the garden. No reaction. Everyone was moving. Pure comedy. And something else.

An illusion, two girls. Then gone.

How to explain.

Before that. I had a conversation with Macartney, the British chargé d’affaires…

Pain…. It burns, now it burns again. Let us wait now, Philip. Steady, steady now. More…

The business of war

30 September 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Lahti (‘Slaughter’, WSOY 2004). Introduction by Jarmo Papinniemi

Major Tuppervaara put his plate down on a tree stump and walked over towards us. He had long legs and walked with a spring in his step. Twigs crunched beneath every step.

‘Okay, boys,’ he said. ‘Peckish?’

‘Yes.’

‘Take your time and listen carefully to what I’m about to tell you. The training exercise will begin soon. Your job is to help out here, you’ll be doing the medical officers’ jobs, all things you’re familiar with. During the course of this drill you will see things you have never seen before. You must not tell anyone about them. I repeat: no one. Not your father, not your mother’ not your girlfriend or your mates, not even the staff at your divisions. No one. That’s an order. Is that clear?’

‘Yes, Sir,’ said Äyräpää. Hiitola and I nodded. More…

Daddy’s girl

30 September 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Maskrosguden (‘The dandelion god’, Söderströms, 2004). Introduction by Maria Antas

The best cinema in town was in the main square. The other was a little way off. It was in the main square too, but you couldn’t compare it to the Royal. At the Grand there was hardly any room between the rows, the floor was flat and there was a dance-hall on the other side of the wall, so that Zorro rode out of time with waltzes, in time with oompahs, out of time with the slow steps of tangos and in time with quick numbers. The Royal was different and had a sloping floor.

Inside, the Royal was several hundred metres long. You could buy sweets on one side and tickets on the other. From Martina Wallin’s mum. She was refined. So was everyone except us: Mum, Dad and me. More…

A toast before dying

30 June 2005 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Voin jo paljon paremmin. Tšehov Badenweilerissa (‘I already feel much better. Chekhov in Badenweiler’, Loki, 2004). Introduction by Hannu Marttila

I went to meet them Friday and I did not plan to take other patients that week. They had a small but comfortable room with striped wallpaper.

The Russian was a tall man, but stooped. It soon became apparent that his wife spoke fluent German because she was of German descent. That made it much easier to take care of things.

Of course I knew who the patient was. I have always enjoyed literature and other forms of art. I could play several pieces rather well on the piano. When I was younger I had even written a couple of stories set in the mountains, though I had never offered them for publication. As for Chekhov, I had read a couple of his stories that had just come out in German translation, and I had liked them quite a lot in a way, even though they of course reflected that characteristic Russian nature, with its vodka and untidiness.

The patient’s wife seized both my hands when I entered. It was a bit confusing, but not necessarily unpleasant.

‘Our name is Chekhov. We have come from Russia,’ the woman said in a strong, carrying voice. ‘I trust you’ve been told?’ More…

Choosing a play

30 September 1981 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Leiri (‘The camp’). Introduction by Vesa Karonen

The local amateurs were having their theatre club meeting on a Friday evening in the main part of the parish hall. It was late August, the light was beginning to fade and no one had remembered to put the lights on. First the stage grew dark, then the floor, then the ceiling. The light lingered on the inside wall for the longest. There were creaks and groans from the rooms at the back and from the attic. The caretaker had been moving around in there about three in the afternoon, and his traces lingered, as they do in old buildings.

“Something of that sort but short, and it’s got to be bloody funny,” said the chairman, a carpenter called Ranta.

In the store cupboard there were 108 old scripts. Tammilehto, the secretary, hauled out about 30 scripts onto the table. His job was running a kiosk down the road.

“Nothing out of date,” said Ranta.

“There’s got to be a bit of love in it, I say,” said Mrs Ranta.

She had a taxi-driver’s cap on her head and was wearing a man’s grey summer jacket, a white shirt and a blue tie. Her car could be seen from the window. It was in the yard. She always parked her car so it could be seen from inside. More…

Boys Own, Girls Own? –

Gender, sex and identity

30 December 2008 | Essays, Non-fiction

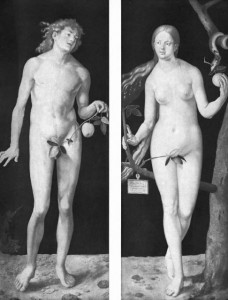

Knowing good and evil: Adam and Eve (Albrecht Dürer, 1507)

In Finnish fiction of the present decade, both in poetry and in prose, there seems to be at least one principle that cuts across all genres: an overt expression of gender, writes the critic Mervi Kantokorpi in her essay

Relationships and family have always been central concerns of literature; questions about gender and individual identity have received a new emphasis in Finnish literature from one season to the next. The gender roles represented in contemporary literature appear to become ever more stereotypical. The question is no longer only of the author consciously setting his or her gender up as the starting point for expression, as has already long been the case with modern literature written by women. More…

Hilda Husso

31 March 1980 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Kun on tunteet (‘When you have feelings’,1913). Introduction by Irmeli Niemi

A Phone call between Hotels

‘Hello – is that the Francesca?’

‘— — —’

‘I’d like to speak to Mr Aksel Lundqvist, the maître d’hotel, if it’s possible, please.’

‘— — —’

‘Oh, I see, that is Mr Lundqvist. I’m ringing from the Iris Hotel. It’s Hilda Husso here – do you remember me, Mr Lundqvist?’

‘— — —’

‘I used to be at Ekbom’s, as a cleaner, in the Brasserie, and I got pregnant – it was a boy, you may remember?’

‘— — —’

‘Hello, what was that, I can’t hear?’ More…