Search results for "jarkko laine prize"

We Finns

15 January 2010 | Columns, Tales of a journalist

Is it so bad to criticise a Finn, if you’re a Finn? Columnist Jyrki Lehtola takes another look at what you think about us Finns out there

Recently, the word ’Finland’ has been repeated in Finland, and generalisations made about what we Finns are like.

Last year saw the seventieth anniversary of the Winter War, and we congratulated ourselves on what a fine fighting nation we are.

A government branding work group tells us at regular intervals how creative a nation we are.

From time to time someone remembers to mention the sauna, while someone else is a little more critical and says we are also an envious nation. More…

In praise of idleness (and fun)

21 December 2012 | Letter from the Editors

As the days grow shorter, here in the far north, and we celebrate the midwinter solstice, Christmas and the New Year, everything begins to wind down. Even here in Helsinki, the sun barely seems to struggle over the horizon; and the raw cold of the viima wind from the Baltic makes our thoughts turn inward, to cosy evenings at home, engaging in the traditional activities of baking, making handicrafts, reading, lying on the sofa and eating to excess.

It is a time to turn to the inner self, to feed the imagination, to turn one’s back on the world of effort and achievement. To light a candle and perhaps do absolutely nothing – which can in itself be a form of meditation.

That’s what we at Books from Finland will be trying to do, anyway. Support in our endeavour comes from an unlikely quarter. In 1932 the British philosopher Bertrand Russell published an essay entitled ‘In Praise of Idleness’, in which he argued cogently for a four-hour working day. ‘I think that there is far too much work done in the world,’ he wrote; ‘that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous’.

Russell was no slouch, as his list of publications alone shows. But his argument was a serious one, and we mean to put it into practice, at least over the twelve days of Christmas. ‘The road to happiness and prosperity,’ he wrote, ‘lies in an organised diminution of work.’ More…

Maailman paras maa [The best country in the world]

14 March 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Maailman paras maa

Maailman paras maa

[The best country in the world]

Toim. [Ed. by] Anu Koivunen

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2012. 255 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-347-0

€ 37, paperback

In this book twelve writers, representing various fields of research, ponder Finland and Finnishness from the viewpoint of history, ethnology, society, culture and economics. Finland-Swedishness and the relationship between Finns and Russians, the need of Finns to defend their participation in the Second World War in alliance with Germany as a ‘separate war’, and the nostalgia related to lost Karelia. The articles deal with Finland facing economic challenges, attitudes towards foreign beggars and self-critical Finnish opinion pieces. They also take a look at Finnish man as portrayed in the classic novel Seitsemän veljestä (‘The seven brothers’, 1870, by Aleksis Kivi) and in a recent prize-winning film about men talking in the sauna about their feelings, and discuss the relationship of the two national languages, Finnish and Swedish. Well-written and original articles question truisms and challenge the reader contemplate his or her own relationship with Finnishness.

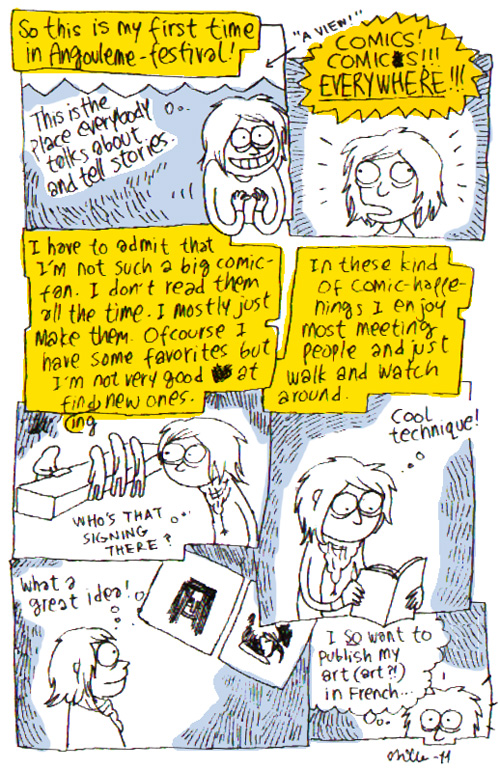

Serious comics: Angoulême 2011

24 February 2011 | This 'n' that

Graphic artist Milla Paloniemi went to Angoulême, too: read more through the link (Milla Paloniemi) in the text below

As a little girl in Paris, I dreamed of going to the Angoulême comics festival – Corto Maltese and Mike Blueberry were my heroes, and I liked to imagine meeting them in person.

20 years later, my wish came true – I went to the festival to present Finnish comics to a French audience! I was an intern at FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange, and for the first time, FILI had its own stand at Angoulême in January 2011.

Finnish comics have become popular abroad in recent years, which is particularly apparent in the young artists’ reception by readers in Europe. Angoulême isn’t just a comics Mecca for Europeans, however: there were admirers of Matti Hagelberg, Marko Turunen and Tommi Musturi from as far away as Japan and Korea.

The festival provides opportunities to present both general ‘official’ comics, ‘out-of-the-ordinary’ and unusual works. The atmosphere at the festival is much wilder than at a traditional book fair: for four days the city is filled with publishers, readers, enthusiasts, artists, and even musicians. People meet in the evenings at le Chat Noir bar to discuss the day’s finds, sketching their friends and the day’s events.

As one Belgian publisher told me, ‘There have always been Finns at Angoulême.’ Staff from comics publisher Kutikuti and many others have been making the rounds at Angoulême for years, walking through the city and festival grounds, carrying their backpacks loaded with books. They have been the forerunners to whom we are grateful, and we hope that our collaboration with them deepens in the future.

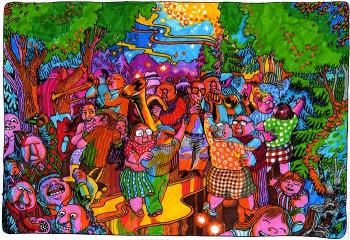

Aapo Rapi: Meti (Kutikuti, 2010)

This year two Finnish artists, Aapo Rapi and Ville Ranta were nominated for the Sélection Officielle prize, which gave them wider recognition. Rapi’s Meti is a colourful graphic novel inspired by his own grandmother Meti [see the picture right: the old lady with square glasses].

Hannu Lukkarinen and Juha Ruusuvuori were also favorites, as all the available copies of Les Ossements de Saint Henrik, the French translation of their adventures of Nicholas Grisefoth, sold out. There were also fans of women comics artists, searching feverishly for works by such artists as Jenni Rope and Milla Paloniemi.

Chatting with French publishers and readers, it became clear that Finnish comics are interesting for their freshness and freedom. Finnish artists dare to try every kind of technique and they don’t get bogged down in questions of genre. They said so themselves at the festival’s public event. According to Ville Ranta, the commercial aspect isn’t the most important thing, because comics are still a marginalised art in Finland. Aapo Rapi claimed that ‘the first thing is to express my own ideas, for myself and a couple of friends, then I look to see if it might interest other people.’

Hannu Lukkarinen emphasised that it’s hard to distribute Finnish-language comics to the larger world: for that you need a no-nonsense agent like Kirsi Kinnunen, who has lived in France for a long time doing publicity and translation work. Finnish publishers haven’t yet shown much interest in marketing comics, but that may change in the future.

These Finnish artists, many of them also publishers, were happy at Angoulême. Happy enough, no doubt, to last them until next year!

Translated by Lola Rogers

Mikko Ylikangas: Unileipää, kuolonvettä, spiidiä. Huumeet Suomessa 1800–1950 [Opium, death’s tincture, speed. Drugs in Finland 1800–1950]

29 April 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Unileipää, kuolonvettä, spiidiä. Huumeet Suomessa 1800–1950

Unileipää, kuolonvettä, spiidiä. Huumeet Suomessa 1800–1950

[Opium, death’s tincture, speed. Drugs in Finland 1800–1950]

Jyväskylä: Atena, 2009. 264 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-796-578-1

€ 34, hardback

This book presents an account of the history of drugs in Finland, as well as changes in legal and illegal drug use. Even in the early 19th century, the authorities were concerned about opium abuse. Medical doctor Elias Lönnrot – best known for collecting the folk poems that make up the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic – coined the name ‘unileipä’, ‘the staff of dreams’, for opium. A period of prohibition of alcohol in the 1920s spurred a huge increase in the sale of cocaine; in the 1930s Finland led the Western world in consumption of heroin as a cough suppressant. In the late 1940s, the United Nations investigated why Finland, with a population of four million, consumed as much heroin in a year as other countries did over an average of 25 years. This was explained by the severity of wartime conditions: drugs were used to maintain battle readiness and to combat anxiety, sleeplessness and tuberculosis. Social problems caused by misuse did not, however, get out of control. This book was awarded a prize for the best science book of the year in Finland in 2009.

And the winner is…

27 November 2009 | In the news

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2009, worth €30,000, is Borgå 1809. Ceremoni och fest (‘Borgå [Porvoo] 1809. Ceremony and feast’) by historian Henrika Tandefelt (born 1972; see this review).

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2009, worth €30,000, is Borgå 1809. Ceremoni och fest (‘Borgå [Porvoo] 1809. Ceremony and feast’) by historian Henrika Tandefelt (born 1972; see this review).

The final choice was made by Björn Wahlroos, Chairman of the Board of the Sampo Insurance Group. No doubt the historical period described in Tandefelt’s book is of great interest to Wahlroos, as he is the owner of the Åminne (in Finnish, Joensuu) estate, which is located in the south-west of Finland and dates from the 18th century. Wahlroos has recently restored the manor house to its full 19th-century glory. The Åminne estate was once the home of Gustaf Mauritz Armfelt, a Finnish-born statesman and officer. Armfelt was also King Gustav III’s trusted adviser – and later adjutant-general under Tsar Alexander I in St Petersburg, and finally, before his death, governor-general of Finland (1813). More…

Juha Seppälä: Paholaisen haarukka [The Devil’s fork]

30 December 2008 | Mini reviews

Paholaisen haarukka

Paholaisen haarukka

[The Devil’s fork]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2008. 267 p.

ISBN 978-951-0-34534-4

€ 32, hardback

Seldom does a novel manage to be as topical as Juha Seppälä’s latest – his tenth – which portrays a great economic crisis and the people who are dragged along with it. Seppälä has written lines for his characters where they claim that a novel is only able to depict a reality that existed years ago – but Paholaisen haarukka proves this is not true. More…

Fatherlands, mother tongues?

12 April 2013 | Letter from the Editors

Patron saint of translators: St Jerome (d. 420), translating the Bible into Latin. Pieter Coecke van Aelst, ca 1530. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Photo: Wikipedia

Finnish is spoken mostly in Finland, whereas English is spoken everywhere. A Finnish writer, however, doesn’t necessarily write in any of Finland’s three national languages (Finnish, Swedish and Sámi).

What is a Finnish book, then – and (something of particular interest to us here at the Books from Finland offices) is it the same thing as a book from Finland? Let’s take a look at a few examples of how languages – and fatherlands – fluctuate.

Hannu Rajaniemi has Finnish as his mother tongue, but has written two sci-fi novels in English, which were published in England. A Doctor in Physics specialising in string theory, Rajaniemi works at Edinburgh University and lives in Scotland. His books have been translated into Finnish; the second one, The Fractal Prince / Fraktaaliruhtinas (2012) was in March 2013 on fifth place on the list of the best-selling books in Finland. (Here, a sample from his first book, The Quantum Thief, 2011, Gollancz.)

Emmi Itäranta, a Finn who lives in Canterbury, England, published her first novel, Teemestarin tarina (‘The tea master’s book’, Teos, 2012), in Finland. She rewrote it in English and it will be published as Memory of Water in England, the United States and Australia (HarperCollins Voyager) in 2014. Translations into six other languages will follow. More…

Panu Rajala: Hirmuinen humoristi. Veikko Huovisen satiirit ja savotat [The awesome humorist. The satires and logging sites of Veikko Huovinen]

16 May 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Hirmuinen humoristi. Veikko Huovisen satiirit ja savotat

Hirmuinen humoristi. Veikko Huovisen satiirit ja savotat

[The awesome humorist. The satires and logging sites of Veikko Huovinen]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2012. 310 p.

ISBN 978-951-0-38952-2

€38, hardback

Author Veikko Huovinen (1927–2009) became widely popular with the publication of his novel Havukka-ahon ajattelija (‘The backwoods philosopher’, 1952). Huovinen, who trained as a forest ranger, spent his life mainly in north-eastern Finland and did not like publicity; the author and theatre scholar Panu Rajala deals with Huovinen’s biography relatively briefly, focusing on a thematic analysis of Huovinen’s extensive and thematically rich output of novels and short stories. He places the the books in the context of Finnish literature, and also examines their film and television adaptations. Huovinen was an intellectually conservative, a highly original humorist; among his books are satirical biographies of Hitler and Stalin. His prose fiction, set in the natural wilds of the North, has not always won the appreciation of pro-modernist critics. Huovinen’s lively and original language is not easy to translate – for example, his only work published in English is a beautiful documentary novel Puukansan tarina (‘Tale of the forest folk’), which received a Finlandia Prize nomination in 1984.

Translated by David McDuff

Utopia or dystopia?

15 October 2013 | This 'n' that

‘The fate of our societies lies in equity’, claims Martti Ahtisaari – winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2008 – in his foreword to a study entitled A recipe for a better life: Experiences from the Nordic countries (2013).

‘The fate of our societies lies in equity’, claims Martti Ahtisaari – winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2008 – in his foreword to a study entitled A recipe for a better life: Experiences from the Nordic countries (2013).

The study was compiled and written by Heikki Hiilamo and Olli Kangas with Johan Fritzell, Jon Kvist and Joakim Palme and published by Crisis Management Initiative (a Finnish, independent, non-profit organisation founded in 2000 by Ahtisaari, President of Finland from 1994 to 2000). It is available here.

‘The Nordic experience’ is presented in chapters dealing with the trustworthiness of the society, the role of the state, the amount of efficiency and inefficiency as well as the homogeneity of the Nordic societies and the social investments of these societies in their citizens.

(The Nordic countries consist of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden as well as their associated territories – with different levels of autonomy – the Faroe Islands and Greenland [Denmark] and Åland [Finland].)

‘"The Nordic enigma" is a successful marriage between hard-core competitive capitalism

and the pursuit of egalitarian policies’.

The study provides a concise summary of how these societies function with additional comments on the socio-historical development of independent Finland. It presents the reader with pros and cons, arguments and facts.

‘For some analysts the Nordic welfare state is a dystopia to be avoided at all costs....

It is simply argued that that the welfare state destroys the incentives to work.’

‘Despite their strong welfare states and heavy tax burdens – often said to be poison

to competitiveness – the Nordic countries are doing well in economic terms.’

The reader is indeed challenged to ponder the best recipes for a better life. Last but not least: how will the ‘recipes’ need to be adapted in the future?

Changes of self and perspective – and even of gender – fascinate the chameleon-like writer, dramatist and actress Pirkko Saisio. Set in Helsinki in the 1950s and 1960s, her autobiographical novel Pienin yhteinen jaettava (‘Lowest common multiple’, 1998) was on the shortlist for the Finlandia Prize. ‘We look into the mirror,’ she says in this introduction to her writing, ‘to wonder at the fact that we have the ability to divide in two, into she who looks and she who is looked at’.

Changes of self and perspective – and even of gender – fascinate the chameleon-like writer, dramatist and actress Pirkko Saisio. Set in Helsinki in the 1950s and 1960s, her autobiographical novel Pienin yhteinen jaettava (‘Lowest common multiple’, 1998) was on the shortlist for the Finlandia Prize. ‘We look into the mirror,’ she says in this introduction to her writing, ‘to wonder at the fact that we have the ability to divide in two, into she who looks and she who is looked at’.