Search results for "jarkko/2009/09/what-god-said"

The blow-flower boy and the heaven-fixer

31 December 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Puhalluskukkapoika ja taivaankorjaaja (‘The blow-flower boy and the heaven-fixer’, 1983). Interview by Olavi Jama

Cold.

A chill west wind came over the blue ice. It went right to the skin through woollen clothes. Shivers ran up and down the spine, made shoulders shake.

In the bank of clouds close to the horizon, right where the icebreaker had crunched open a passage to the shore, hung a pale blotch, a substitute for the sun. It gave off more chill than warmth.

Lennu’s teeth were chattering.

He wore a buttoned-up windbreaker, a hand-me-down from Gunnar, over a heavy lambswool shirt. It couldn’t keep off the cold. More…

Melba, Mallinen and me

30 June 1993 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Fallet Bruus (‘The Bruus case’, Söderströms, 1992; in Finnish, Tapaus Bruus, Otava), a collection of short stories

After the war Helsingfors began to grow in earnest.

Construction started in Mejlans [Meilahti] and Brunakärr [Ruskeasuo]. People who moved there wondered if all the stone in the country had been damaged by the bombing or if all the competent builders had been killed; if you hammered a nail into a wall you were liable to hammer it right into the back of your neighbor’s head and risk getting indicted for manslaughter.

Then the Olympic Village in Kottby [Käpylä] was built, and for a few weeks in the summer of 1952 this area of wood-frame houses became a legitimate part of the city that housed such luminaries as the long-legged hop-skip-and-jump champion Da Silva, the runner Emil Zatopek (with the heavily wobbling head), the huge heavyweight boxer Ed Saunders and the somewhat smaller heavyweight Ingemar Johansson who had to run for his life from Saunders. More…

The many arms of Krishna

14 August 2014 | Extracts, Non-fiction

A feast by the Ganges. Photo from Pirjo Honkasalo’s film Atman

Cinematographer, camerawoman and director Pirjo Honkasalo has travelled and filmed widely – Japan, Estonia, India, Chechnya, Ingushetia, Russia – and her documentary films in particular have gained fame. American film critic John Anderson interviews Honkasalo; they talk about her documentary film Atman (1996) about a pilgrimage in India.

Edited extracts from Armoton kauneus. Pirjo Honkasalon elokuvataide (‘Merciless beauty. The film art of Pirjo Honkasalo’, Siltala, 2014; translated from English into Finnish by Leena Tamminen)

You can almost catch a whiff of the Ganges watching Atman [Hindu term, ‘self’], a documentary film in which religious pilgrimage, devotion, exhilaration and hysteria compete with tormented bodies, physical mortification, corpses, pollution and the acrid smoke of ritual cremation for domination of the viewer’s senses. The fact that it won the top prize at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam in 1996 proves there is, if not justice, then good taste in the world. With all due respect to her previous work, Atman signified the full manifestation of Honkasalo’s genius.

What is it about? Eternity. Also, Jamana Lal: a member of the low-caste of Baila, a wifeless, crippled devotee of Lord Shiva whose mother has died, and who must – according to Hindu tradition – take her ashes from the ostensible mouth of the Ganges to the foothills of the Himalayas. More…

Dog

30 September 2002 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Afrikasta on paljon kertomatta (‘Much is still untold about Africa’, WSOY, 2002). Introduction by Maria Säntti

You’re exactly what a dog should be, I told him. You’ve a black ear and a white one. You’re not too big and you’re not all teeth.

I stroked his black-spotted coat. He wagged his curly tail.

I crouched down. He squeezed up against my chest. I sent my ball rolling along the stairway corridor. He shot after it, accidentally running over the top of it. As he braked, his claws screeched on the tiles. Sparks went flying.

He snapped the ball in his jaws, nibbled its plastic and sent it back with a snuffle. His tongue was wagging with glee. Next I wanted to roll the ball so he wouldn’t get it. It bumped against the iron banister and went off in a different direction, skidding under the dog’s belly. He turned and dashed after it. More…

Here and there

11 September 2009 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Extracts and photographs from Jotain on tapahtunut /Something happened (Musta Taide, 2009; translation by Jüri Kokkonen)

News photos document dramatic, dangerous or tragic incidents – but the photojournalist Markus Jokela is interested in documenting ordinary, domestic and everyday life, be it in Iraq, Russia, Biafra or Sri Lanka. These photographs, with commentaries, are taken from his new book, Jotain on tapahtunut / Something happened (2009), offering glimpses of life in contemporary Finland and in the United States

News photos document dramatic, dangerous or tragic incidents – but the photojournalist Markus Jokela is interested in documenting ordinary, domestic and everyday life, be it in Iraq, Russia, Biafra or Sri Lanka. These photographs, with commentaries, are taken from his new book, Jotain on tapahtunut / Something happened (2009), offering glimpses of life in contemporary Finland and in the United States

I’ve never been particularly enthusiastic about individual news photos, especially about taking them.

A good news photo has to state things bluntly and it has to be quite simple in visual terms. It must open up immediately to the viewer.

But the images in photo reportages do not have to scream simplified truths. They can whisper and ask, and open up gradually. One can come back to them. The reportage is something personal. Though a poor medium for telling about the complex facts of the world, it can provide experiences that survive. More…

Tutti frutti

20 November 2009 | In the news

The chair of the jury for the Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2009, Professor Pekka Puska, compared choosing a winner to the dilemma of choosing between oranges and bananas. The jury found that among the entries were at least 20 or 30 books that could have gone on the final shortlist of six titles. More…

The chair of the jury for the Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2009, Professor Pekka Puska, compared choosing a winner to the dilemma of choosing between oranges and bananas. The jury found that among the entries were at least 20 or 30 books that could have gone on the final shortlist of six titles. More…

The dog-man’s daughter

30 December 2001 | Fiction

Extracts from the radio play Porkkalansaari (‘The island of Porkkala’, the Finnish Broadcasting Company, 1993)

Extracts from the radio play Porkkalansaari (‘The island of Porkkala’, the Finnish Broadcasting Company, 1993)

The surface of the earth is the first to freeze; then the still waters. The sea freezes at the shore often at the same time, on the same night, as the slow-flowing brooks. I have watched them for many years. When you live in the same place for a long time, you notice this much: that almost everything just repeats and repeats.

It flows into a plastic tube. I suppose water flows inside it. You could drop matchsticks in on the other side of the road and wait on this side for them to swim through the drum. You’d only have to find one; that would be enough to prove it. More…

In the north

30 September 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Luvaton elämä (‘Forbidden life’, 1987). Introduction by Tero Liukkonen

I

I went up north in a sleeping car. It was a relief to see that even in Tampere there was a sign on the car saying ‘Kemijärvi’. That meant I could sleep the whole way. I had the lower berth; a couple more like me were sleeping in the same compartment – just ordinary women. I was nevertheless silent and reserved, so that neither of them would want to make me into a travelling companion. And they did leave me in peace.

I read for a bit, till I began to feel more at home, and settled down to sleep with my woollen socks on. I deliberately went almost to sleep while not wanting to drop off completely; and I gradually reached a point where I didn’t know which direction the train was going in. That was liberating. It was all the same which direction we were going in. The motion of the train got through to my nerves and started releasing things. More…

The Monkey

30 June 1981 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Dockskåpet (‘The doll’s house’). Introduction and translation by W. Glyn Jones

The newspaper came at five o’clock, as it did every morning. He lit the bedside lamp and put on his slippers. Very slowly he shuffled across the smooth concrete floor, threading his way as usual between the modeling stands; the shadows they cast were black and cave-like. He had polished the floor since last making some plaster casts. There was a wind blowing, and in the light from the street lamp outside the studio the shadows were swaying to and fro, forced away from each other and then brought together again: it was like walking through a moonlit forest in a gale. He liked it. The monkey had wakened up in its cage and was hanging on to the bars, squealing plaintively. “Monk-monk,” said the sculptor as he went out into the hall to fetch his newspaper. On his way back he opened the door of the cage, and the monkey scrambled on to his shoulder and held on tight. She was cold. He put her collar on and fastened the lead to his wrist. She was a quite ordinary guenon from Tangier that someone had bought cheap and sold at a large profit: she got pneumonia now and then and had to be given penicillin. The local children made jerseys for her. He went back to bed and opened his newspaper. The monkey lay still, warming herself with her arms around his neck. Before long she sat down in front of him with her beautiful hands clasped across her stomach; she fixed her eyes on his. Her narrow, grey face betrayed a patience that was sad and unchanging. “Go on – stare, you confouded orangoutang,” the sculptor said and went on reading. When he reached the second or third page the monkey would suddenly and with lightning precision jump through the newspaper, but always through the pages he was finished with. It was a ritual act. The newspaper is torn apart, the monkey shrieks in a triumph and lies down to sleep. It can give you some relief to read about all the worthless nonsense that goes on in the world every morning at five o’clock and then to have it confirmed that it is worthless nonsense when the whole lot is made unreadable by a great hole being made through it. She helped him to get rid of it. More…

Locomotive

30 June 1981 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Dockskåpet (‘The doll’s house’). Introduction and translation by W. Glyn Jones

What I am about to write might perhaps seem exaggerated, but the most important element in what I have to tell is really my overriding desire for accuracy and attention to detail. In actual fact, I am not telling a story, I am writing an account. I am known for my accuracy and precision. And what I am trying to say is intended for myself: I want to get certain things into perspective.

It is hard to write; I don’t know where to begin. Perhaps a few facts first. Well, I am a specialist in technical drawings and have been employed by Finnish Railways all my life. I am a meticulous and able draughtsman; in addition to that I have for many years worked as a secretary; I shall return to this later. To a very great extent my story is concerned with locomotives; I am consciously using this slightly antiquated word locomotive instead of loco, for I have a penchant for beautiful and perhaps somewhat antediluvian words. Of course, I often draw detailed sketches of this particular kind of engine as part of my everyday work, and when I am so engaged I feel no more than a quiet pride in my work, but in the evenings when I have gone home to my flat I draw engines in motion and in particular the locomotive. It is a game, a hobby, which must not be associated with ambition. During recent years I have drawn and coloured a whole series of plates, and I think that I might be able to produce a book of them some time. But I am not ready yet, not by a long way. When I retire I shall devote all my time to the locomotive, or rather to the idea of the locomotive. At the moment I am forced to write, every day; I must be explicit. The pictures are not sufficient. More…

The Paradox Archive

30 September 1991 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Umbra (WSOY, 1990). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

The Paradox Archive

Umbra was a man of order. His profession alone made him that, for sickness was a disorder, and death chaos.

But life demands disorder, since it calls for energy, for warmth – which is disorder. Abnormal effort did perhaps enhance order within a small and carefully defined area, but it squandered considerable energy, and ultimately the disorder in the environment was only intensified.

Umbra saw that apparent order concealed latent chaos and collapse, but he knew too that apparent chaos contained its own order. More…

Six letters

31 March 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Tainaron (1985). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

The whirr of the wheel

Letter II

I awoke in the night to sounds of rattling and tinkling from my kitchen alcove. Tainaron, as you probably know, lies within a volcanic zone. The experts say that we have now entered a period in which a great upheaval can be expected, one so devastating that it may destroy the city entirely.

But what of that? You need not imagine that it makes any difference to the Tainaronians’ way of living. The tremors during the night are forgotten, and in the dazzle of the morning, as I take my customary short cut across the market square, the open fruit-baskets glow with their honeyed haze, and the pavement underfoot is eternal again.

And in the evening I gaze at the huge Wheel of Earth, set on its hill and backed by thundercloud, with circumference, poles and axis pricked out in thousands of starry lights. The Wheel of Earth, the Wheel of Fortune… Sometimes its turning holds me fascinated, and even in my sleep I seem to hear the wheel’s unceasing hum, the voice of Tainaron itself. More…

The mighty word

15 November 2012 | Fiction, Prose

‘Mahtisana’, a short story from the collection Lapsia (‘Children’, 1895). Introduction by Mervi Kantokorpi

Mother and Dad hadn’t said a single word to each other since lunchtime. The children, Maija and Iikka, were quiet, too. They sat apart, Iikka on the chair at the end of the sofa, where he could see the moon through the window, and Maija next to the window looking out on the street, where children moved about on skis and sleds. They didn’t dare make a sound, not even a whisper to ask for permission to go outside. It had been so quiet all that Sunday evening that when Mother spoke, encouraging them to go out and play, both of them nearly jumped.

They left without saying a word, Maija creeping quite silently. Even out in the courtyard she and Iikka still spoke in whispers as they decided which hill to go to. They didn’t really want to go anywhere, but when they came out to the street and could hear the happy shouts of children from every direction, it refreshed their spirits. Maija sat Iikka down on the sled and set off at a run, pulling him behind her. She felt as if her gloomy mood was falling away in pieces to be trampled underfoot.

A few streets down there was a large crowd of boys on the corner. They decided to go and see what was happening. More…

Manmother

31 December 2002 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Granaattiomena (‘Pomegranate’, WSOY, 2002). Introduction by Kristina Carlson

The journey

Mother had sent her son to the island of Rome.

She’d sent him for pleasure and recreation, and also to have a little time by herself. Even though their life together was on an even keel, it was sensible to have some time away from each other. She herself was sixty-eight, and her son an unmarried hermit in his thirties, on sickness allowance for the last couple of years. He was afflicted with chronic depression. The doctors had been unable to identify the cause. The origin of a disorder of that sort was often looked for in some infant trauma; but the boy’s childhood, from all appearances, had been harmonious. One doctor suspected the time of his father’s terminal illness, when the boy had had to nurse his father for a long while. More…

Rock or baroque?

30 April 2014 | Extracts, Non-fiction

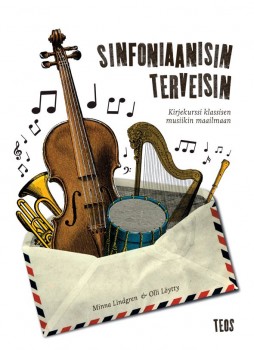

What if your old favourites lose their flavour? Could there be a way of broadening one’s views? Scholar Olli Löytty began thinking that there might be more to music than 1980s rock, so he turned to the music writer Minna Lindgren who was delighted by the chance of introducing him the enormous garden of classical music. In their correspondence they discussed – and argued about – the creativity of orchestra musicians, the significance of rhythm and whether the emotional approach to music might not be the only one. Their letters, from 2009 to 2013, an entertaining musical conversation, became a book. Extracts from Sinfoniaanisin terveisin. Kirjekurssi klassisen musiikin maailmaan (‘With symphonical greetings. A correspondence course in classical music’)

What if your old favourites lose their flavour? Could there be a way of broadening one’s views? Scholar Olli Löytty began thinking that there might be more to music than 1980s rock, so he turned to the music writer Minna Lindgren who was delighted by the chance of introducing him the enormous garden of classical music. In their correspondence they discussed – and argued about – the creativity of orchestra musicians, the significance of rhythm and whether the emotional approach to music might not be the only one. Their letters, from 2009 to 2013, an entertaining musical conversation, became a book. Extracts from Sinfoniaanisin terveisin. Kirjekurssi klassisen musiikin maailmaan (‘With symphonical greetings. A correspondence course in classical music’)

Olli, 19 March, 2009

Dear expert,

I never imagined that the day would come when I would say that rock had begun to sound rather boring. There are seldom, any more, the moments when some piece sweeps you away and makes you want to listen to more of the same. I derive my greatest enjoyment from the favourites of my youth, and that is, I think, rather alarming, as I consider people to be naturally curious beings whom new experiences, extending their range of experiences and sensations, brings nothing but good.

Singing along, with practised wistfulness, to Eppu Normaali’s ‘Murheellisten laulujen maa’ (‘The land of sad songs’) alone in the car doesn’t provide much in the way of inspiration. It really is time to find something new to listen to! My situation is already so desperate that I am prepared to seek musical stimulation from as distant a world as classical music. I know more about the African roots of rock than about the birth of western music, the music that is known as classical. But it looks and sounds like such an unapproachable culture that I badly need help on my voyage of exploration. Where should I start, when I don’t really know anything? More…