Search results for "jarkko/2011/04/2010/05/2009/10/writing-and-power"

Finlandia Prize candidates 2011

17 November 2011 | In the news

The candidates for the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011 are Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Kristina Carlson, Laura Gustafsson, Laila Hirvisaari, Rosa Liksom and Jenni Linturi.

The candidates for the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011 are Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Kristina Carlson, Laura Gustafsson, Laila Hirvisaari, Rosa Liksom and Jenni Linturi.

Their novels, respectively, are Kallorumpu (‘Skull drum’, Teos), William N. Päiväkirja (‘William N. Diary’, Otava), Huorasatu (‘Whore tale’, Into), Minä, Katariina (‘I, Catherine’, Otava), Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY) and Isänmaan tähden (‘For fatherland’s sake’, Teos).

Kallorumpu takes place in 1935 in Marshal Mannerheim’s house in Helsinki and in the present time. Laila Hirvisaari is a popular writer of mostly historical fiction: Minä, Katariina, a portrait of Russia’s Catherine the Great, is her 39th novel. Gustafsson’s and Linturi’s novels are first works; the former is a bold farce based on women’s mythology, the latter is about guilt born of the Second World War.

The jury – journalist and critic Hannu Marttila, journalist Tuula Ketonen and translator Kristiina Rikman – made their choice out of 130 novels. The winner, chosen by the theatre manager of the KOM Theatre Pekka Milonoff, will be announced on the first of December. The prize is worth 30,000 euros. It has been awarded since 1984, to novels only from 1993.

The fact that this time all the candidates are women has naturally been the object of criticism: why are the popular male writers’ books of 2011 missing from the list?

Another thing that these novels share is history: five of them are totally or partially set in the past – Finland in 1935, Paris in the 1890s, Russia/Soviet Union in the 18th century and in the 1980s, and 1940s Finland during the Second World War. Even the sixth, Huorasatu, bases its depiction of the present day in women’s prehistory, patriarchy and the ancient myths.

The jury’s chair, Hannu Marttila, commented: ‘This book year is sure to be remembered for a generational and gender change among those who write literature about the Second World War in Finland. Young woman writers describe the war with probably greater diversity than before. From the non-fiction writing of recent years it is clear that the struggles and difficulties of the home front are increasingly being recognised as part of the general struggle for survival, and on the other hand the less heroic aspects of war, the shameful and criminal elements, have also become acceptable as objects of study.’

Marttila concluded his speech: ‘When picking mushrooms in the forest, I have learned that it is often worth humbly peeking under the grass, and that the most glaring cap is not necessarily the best…. Perhaps it is time to forget the old saying that there is literature, and then there is women’s literature.’

Success after success

9 March 2012 | This 'n' that

The women of Purge: Elena Leeve and Tea Ista in Sofi Oksanen's Puhdistus at the Finnish National Theatre, directed by Mika Myllyaho. Photo: Leena Klemelä, 2007

Sofi Oksanen’s Purge, an unparalleled Finnish literary sensation, is running in a production by Arcola Theatre in London, from 22 February to 24 March.

First premiered at the Finnish National Theatre in Helsinki in 2007, Puhdistus, to give it its Finnish title, was subsequently reworked by Oksanen (born 1977) into a novel – her third.

Puhdistus retells the story of her play about two Estonian women, moving through the past in flashbacks between 1939 and 1992. Aliide has experienced the horrors of the Stalin era and the deportation of Estonians to Siberia, but has to cope with the guilt of opportunism and even manslaughter. One night in 1992 she finds a young woman in the courtyard of her house; Zara has just escaped from the claws of members of the Russian mafia who held her as a sex slave. (Maya Jaggi reviewed the novel in London’s Guardian newspaper.) More…

Best Translated Book Award 2011

13 May 2011 | In the news

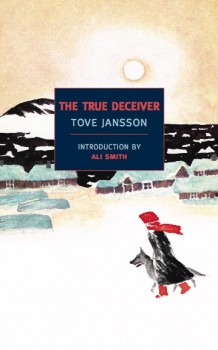

Thomas Teal’s translation from Swedish into English of Tove Jansson’s novel Den ärliga bedragaren (Schildts, 1982), entitled The True Deceiver (published by New York Review Books, 2009), won the 2011 Best Translated Book Award in fiction (worth $5,000; supported by Amazon.com). The winning titles and translators for this year’s awards were announced on 29 April in New York City as part of the PEN World Voices Festival.

Thomas Teal’s translation from Swedish into English of Tove Jansson’s novel Den ärliga bedragaren (Schildts, 1982), entitled The True Deceiver (published by New York Review Books, 2009), won the 2011 Best Translated Book Award in fiction (worth $5,000; supported by Amazon.com). The winning titles and translators for this year’s awards were announced on 29 April in New York City as part of the PEN World Voices Festival.

Organised by Three percent (the link features a YouTube recording from the award ceremony, introducing the translator, Thomas Teal [fast-forward to 7.30 minutes]) at the University of Rochester, and judged by a board of literary professionals, the Best Translated Book Award is ‘the only prize of its kind to honour the best original works of international literature and poetry published in the US over the previous year’. ‘Subtle, engaging and disquieting, The True Deceiver is a masterful study in opposition and confrontation’, said the jury.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001), mother of the Moomintrolls, story-teller and illustrator of children’s books, translated into 40 languages, began to write novels and short stories for adults in her later years. Psychologically sharp studies of relationships, they are written with cool understatement and perception.

Quality writing will work its way into a wider knowledge (i.e. a bigger language and readership) eventually… even though occasionally it may seem difficult to know where exactly it comes from; in a review published in the London Guardian newspaper, the eminent writer Ursula K. Le Guin assumed Tove Jansson was Swedish.

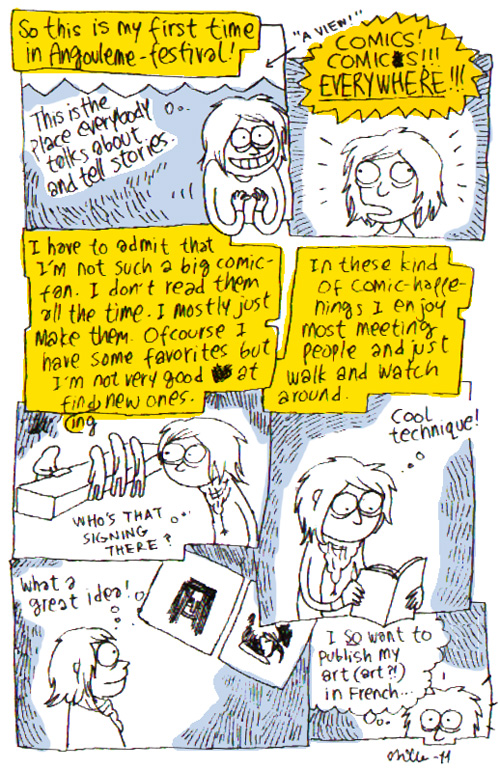

Serious comics: Angoulême 2011

24 February 2011 | This 'n' that

Graphic artist Milla Paloniemi went to Angoulême, too: read more through the link (Milla Paloniemi) in the text below

As a little girl in Paris, I dreamed of going to the Angoulême comics festival – Corto Maltese and Mike Blueberry were my heroes, and I liked to imagine meeting them in person.

20 years later, my wish came true – I went to the festival to present Finnish comics to a French audience! I was an intern at FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange, and for the first time, FILI had its own stand at Angoulême in January 2011.

Finnish comics have become popular abroad in recent years, which is particularly apparent in the young artists’ reception by readers in Europe. Angoulême isn’t just a comics Mecca for Europeans, however: there were admirers of Matti Hagelberg, Marko Turunen and Tommi Musturi from as far away as Japan and Korea.

The festival provides opportunities to present both general ‘official’ comics, ‘out-of-the-ordinary’ and unusual works. The atmosphere at the festival is much wilder than at a traditional book fair: for four days the city is filled with publishers, readers, enthusiasts, artists, and even musicians. People meet in the evenings at le Chat Noir bar to discuss the day’s finds, sketching their friends and the day’s events.

As one Belgian publisher told me, ‘There have always been Finns at Angoulême.’ Staff from comics publisher Kutikuti and many others have been making the rounds at Angoulême for years, walking through the city and festival grounds, carrying their backpacks loaded with books. They have been the forerunners to whom we are grateful, and we hope that our collaboration with them deepens in the future.

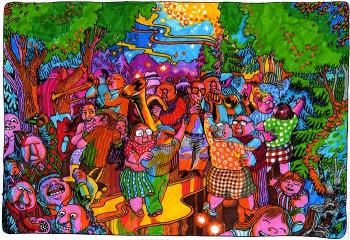

Aapo Rapi: Meti (Kutikuti, 2010)

This year two Finnish artists, Aapo Rapi and Ville Ranta were nominated for the Sélection Officielle prize, which gave them wider recognition. Rapi’s Meti is a colourful graphic novel inspired by his own grandmother Meti [see the picture right: the old lady with square glasses].

Hannu Lukkarinen and Juha Ruusuvuori were also favorites, as all the available copies of Les Ossements de Saint Henrik, the French translation of their adventures of Nicholas Grisefoth, sold out. There were also fans of women comics artists, searching feverishly for works by such artists as Jenni Rope and Milla Paloniemi.

Chatting with French publishers and readers, it became clear that Finnish comics are interesting for their freshness and freedom. Finnish artists dare to try every kind of technique and they don’t get bogged down in questions of genre. They said so themselves at the festival’s public event. According to Ville Ranta, the commercial aspect isn’t the most important thing, because comics are still a marginalised art in Finland. Aapo Rapi claimed that ‘the first thing is to express my own ideas, for myself and a couple of friends, then I look to see if it might interest other people.’

Hannu Lukkarinen emphasised that it’s hard to distribute Finnish-language comics to the larger world: for that you need a no-nonsense agent like Kirsi Kinnunen, who has lived in France for a long time doing publicity and translation work. Finnish publishers haven’t yet shown much interest in marketing comics, but that may change in the future.

These Finnish artists, many of them also publishers, were happy at Angoulême. Happy enough, no doubt, to last them until next year!

Translated by Lola Rogers

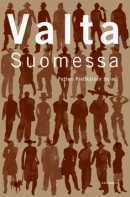

Valta Suomessa [Power in Finland]

5 August 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Valta Suomessa

Valta Suomessa

[Power in Finland]

Toim. [Ed. by] Petteri Pietikäinen

Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 2010. 287 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-495-143-2

33 €, paperback

The authors have been involved in the Academy of Finland’s ‘Power and society in Finland’ research programme, which supports the multidisciplinary study of the historical impact that changes in Finnish society have on its power structures and on those who exert power in Finland. Among the changes are Finland’s accession to the European Union and the internationalisation of corporate and business life. Major power management and policy decisions have often been made without extensive public debate. The articles include studies of the historical changes in economic history and women’s status; other subjects include the conflicts between the forestry industry and nature conservationists; energy policy and the relatively low level of opposition to nuclear power among Finns, labour relations and the opportunities that citizens have to influence media content.

European Union literature prizes 2010

8 October 2010 | In the news

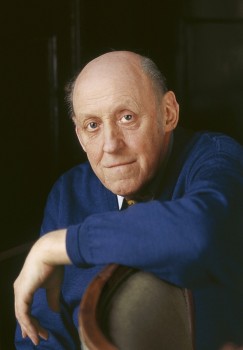

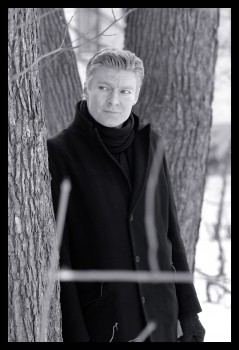

Riku Korhonen. Photo: Harri Pälviranta

With his novel Lääkäriromaani (‘Doctor novel’, Sammakko, 2009), Riku Korhonen (born 1972) is one of the 11 winners of the 2010 European Union Prize for Literature, worth €5,000 each. The winners were announced at Frankfurt Book Fair on 6 October.

The European Commission, the European Booksellers’ Federation (EBF), the European Writers’ Council (EWC) and the Federation of European Publishers (FEP) award the annual prize, which is supported through the European Union’s culture programme. It aims to draw attention to new talents and to promote the publication of their books in different countries, as well as celebrating European cultural diversity. Authors who have published two to four prose works during the last five years and whose work has been translated into two foreign languages at the most are eligible for the prize.

Korhonen has published two novels, a collection of short prose and a collection of poetry. Read translated extracts, published in Books from Finland in 2003, from his first novel, Kahden ja yhden yön tarinoita (‘Tales from two and one nights’, 2003) here. More…

Helsinki Book Fair 2011

2 November 2011 | In the news

President Toomas Hendrik Ilves at the Book Fair: Viro is Estonia in Finnish. Photo: Kimmo Brandt/The Finnish Fair Corporation

The Helsinki Book Fair, held from 27 to 30 October, attracted more visitors than ever before: 81,000 people came to browse and buy books at the stands of nearly 300 exhibitors and to meet more than a thousand writers and performers at almost 700 events.

The Music Fair, the Wine, Food and Good Living event and the sales exhibition of contemporary art, ArtForum, held at the same time at Helsinki’s Exhibition and Convention Centre, expanded the selection of events and – a significant synergetic advantage, of course – shopping facilities. Twenty-eight per cent of the visitors thought this Book Fair was better than the previous one held in 2010.

According to a poll conducted among three hundred visitors, 21 per cent had read an electronic book while only 6 per cent had an e-book reader of their own. Twenty-five per cent did not believe that e-books will exceed the popularity of printed books, and only three per cent believed that e-books would win the competition.

Estonia was the theme country this time. President Toomas Hendrik Ilves of the Republic of Estonia noted in his speech at the opening ceremony: ‘As we know well from the fate of many of our kindred Finno-Ugric languages, not writing could truly mean a slow national demise. So publish or perish has special meaning here. Without a literary culture, we would simply not exist and we have known this for many generations, since the Finnish and Estonian national epics Kalevala and Kalevipoeg. – During the last decade, more original literature and translations have been published in Estonia than ever before. And we need only access the Internet to glimpse the volume of text that is not printed – it is even larger than the printed corpus. We live in an era of flood, not drought, and thus it is no wonder that as a discerning people, we do not want to keep our ideas and wisdom to ourselves but try to share and distribute them more widely. The idea is not to try to conquer the world but simply, with our own words, to be a full participant in global literary culture, and in the intellectual history and future of humankind.’

Finland meets Estonia: authors Sofi Oksanen and Viivi Luik in discussion. Photo: Kimmo Brandt/The Finnish Fair Corporation

The power game

30 June 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Puhua, vastata, opettaa (‘Speak, answer, teach’, 1972) could be called a collection of aphorisms or poems; the pieces resemble prose in having a connected plot, but they certainly are not narrative prose. Ikuisen rauhan aika (‘A time of eternal peace’, 1981) continues this approach. The title alludes ironically to Kant’s Zum Ewigen Frieden, mentioned in the text; ‘eternal peace’ is funereal for Haavikko.

In his ‘aphorisms’ Haavikko is discovering new methods of discourse for his abiding preoccupation: the power game. All organizations, he thinks, observe the rules of this sport – states, armies, businesses, churches. Any powerful institution wages war in its own way, applying the ruthless military code to autonomous survival, control, aggrandizement, and still more power. No morality – the question is: who wins? ‘I often entertain myself by translating historical events into the jargon of business management, or business promotion into war.’

‘What is a goal for the organization is a crime for the individual.’ Is Haavikko an abysmal pessimist, a cynic? He would himself consider that cynicism is something else: a would-be credulous idealism, plucking out its own eyes, promoting evil through ignorance. As for reality, ‘the world – the world’s a chair that’s pulled from under you. No floor’, says Mr Östanskog in the eponymous play. Reading out the rules of a mindless and cruel sport, without frills, softening qualifications, or groundless hopes, Haavikko is in the tradition of those moralists of the Middle Ages, who wrote tracts denouncing the perversity and madness of ‘the world’ – which is ‘full of work-of-art-resembling works of art, in various colours, book-resembling texts, people-resembling people’.

Kai Laitinen

Speak, answer, teach

When people begin to desire equal rights, fair shares, the right to decide for themselves, to choose

one cannot tell them: You are asking for goods that cannot be made.

One cannot say that when they are manufactured they vanish, and when they are increased they decrease all the time. More…

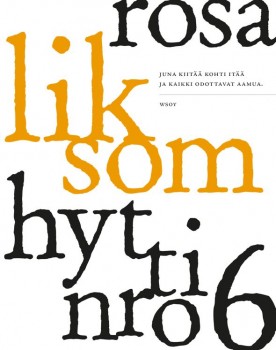

Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011

1 December 2011 | In the news

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011, worth €30,000, is Rosa Liksom, for her novel Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY): read translated extracts and an introduction of the author here on this page.

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011, worth €30,000, is Rosa Liksom, for her novel Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY): read translated extracts and an introduction of the author here on this page.

The prize was awarded on 1 December. The winner was selected by the theatre manager Pekka Milonoff from a shortlist of six.

‘Hytti nro 6 is an extraordinarily compact, poetic and multilayered description of a train journey through Russia. The main character, a girl, leaves Moscow for Siberia, sharing a compartment with a vodka-swilling murderer who tells hair-raising stories about his own life and about the ways of his country. – Liksom is a master of controlled exaggeration. With a couple of carefully chosen brushstrokes, a mini-story, she is able to conjure up an entire human destiny,’ Milonoff commented.

Author and artist Rosa Liksom (alias Anni Ylävaara, born 1958), has since 1985 written novels, short stories, children’s book, comics and plays. Her books have been translated into 16 languages.

Appointed by the Finnish Book Foundation, the prize jury (journalist and critic Hannu Marttila, journalist Tuula Ketonen and translator Kristiina Rikman) shortlisted the following novels: Kallorumpu (‘Skull drum’, Teos) by Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, William N. Päiväkirja (‘William N. Diary’, Otava) by Kristina Carlson, Huorasatu (‘Whore tale’, Into) by Laura Gustafsson, Minä, Katariina (‘I, Catherine’, Otava) by Laila Hirvisaari, and Isänmaan tähden (‘For fatherland’s sake’, first novel; Teos) by Jenni Linturi.

Rosa Liksom travelled a great deal in the Soviet Union in the 1980s. She said she hopes that literature, too, could play a role in promoting co-operation between people, cultures and nations: ‘For the time being there is no chance of some of us being able to live on a different planet.’

Government Prize for Translation 2011

24 November 2011 | In the news

María Martzoúkou. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

The Finnish Government Prize for Translation of Finnish Literature of 2011 – worth € 10,000 – was awarded to the Greek translator and linguist María Martzoúkou.

Martzoúkou (born 1958), who lives in Athens, where she works for the Finnish Institute, has studied Finnish language and literature as well as ancient Greek at the Helsinki University, where she has also taught modern Greek. She was the first Greek translator to publish translations of the Finnish epic, the Kalevala: the first edition, containing ten runes, appeared in 1992, the second, containing ten more, in 2004.

‘Saarikoski was the beginning,’ she says; she became interested in modern Finnish poetry, in particular in the poems of Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983). As Saarikoski also translated Greek literature into Finnish, Martzoúkou found herself doubly interested in his works.

Later she has translated poetry by, among others, Tua Forsström, Paavo Haavikko, Riina Katajavuori, Arto Melleri, Annukka Peura, Pentti Saaritsa, Kirsti Simonsuuri and Caj Westerberg.

Among the Finnish novelists Martzoúkou has translated are Mika Waltari (five novels; the sixth, Turms kuolematon, The Etruscan, is in the printing press), Väinö Linna (Tuntematon sotilas, The Unknown Soldier) and Sofi Oksanen (Puhdistus, Purge).

María Martzoúkou received her award in Helsinki on 22 November from the minister of culture and sports, Paavo Arhinmäki. Thanking Martzoúkou for the work she has done for Finnish fiction, he pointed out that The Finnish Institute in Athens will soon publish a book entitled Kreikka ja Suomen talvisota (‘Greece and the Finnish Winter War’), a study of the relations of Finland and Greece and the news of the Winter War (1939–1940) in the Greek press, and it contains articles by Martzoúkou.

The prize has been awarded – now for the 37th time – by the Ministry of Education and Culture since 1975 on the basis of a recommendation from FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange.

Cityscapes

23 February 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Photographer Stefan Bremer’s home town, Helsinki, provides endless inspiration, material and atmospheric. For forty years Bremer has been recording views of the maritime city, its changing seasons, its cultural events, its people. These images are from his new book – entitled, simply, Helsinki (Teos, 2012)

City kids: day-care outing in Töölönlahti park. Photo: Stefan Bremer, 2010

When I was a child, Helsinki seemed to me a grey and sad town. Stooping, quiet people walked its broad streets. The colours of the houses had been darkened by coal smoke over the years, and new buildings were coated a depressing grey.

A lot has since changed. Today, Helsinki is younger than it was in my youth. More…

A light shining

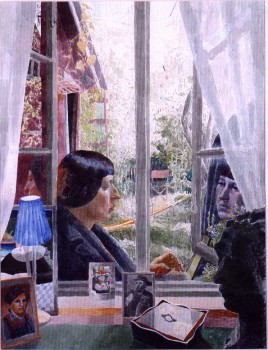

28 July 2011 | Essays, Non-fiction

Portrait of the author: Leena Krohn, watercolour by Marjatta Hanhijoki (1998, WSOY)

In many of Leena Krohn’s books metamorphosis and paradox are central. In this article she takes a look at her own history of reading and writing, which to her are ‘the most human of metamorphoses’. Her first book, Vihreä vallankumous (‘The green revolution’, 1970), was for children; what, if anything, makes writing for children different from writing for adults?

Extracts from an essay published in Luovuuden lähteillä. Lasten- ja nuortenkirjailijat kertovat (‘At the sources of creativity. Writings by authors of books for children and young people’, edited by Päivi Heikkilä-Halttunen; The Finnish Institute for Children’s Literature & BTJ Kustannus, 2010)

What is writing? What is reading? I can still remember clearly the moment when, at the age of five, I saw signs become meanings. I had just woken up and taken down a book my mother had left on top of the chest of drawers, having read to us from it the previous day. It was Pilvihepo (‘The cloud-horse’) by Edith Unnerstad. I opened the book and as my eyes travelled along the lines, I understood what I saw. It was a second awakening, a moment of sudden realisation. I count that morning as one of the most significant of my life.

Learning to read lights up books. The dumb begin to speak. The dead come to life. The black letters look the same as they did before, and yet the change is thrilling. Reading and writing are among the most human of metamorphoses. More…

Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2010

19 November 2010 | In the news

A massive tome running to 1,000 pages by Vesa Sirén, journalist and music critic of the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper, features Finnish conductors from the 1880s to the present day. On 18 November it became the recipient of the 2010 Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction by the Finnish Book Foundation, worth €30,000.

A massive tome running to 1,000 pages by Vesa Sirén, journalist and music critic of the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper, features Finnish conductors from the 1880s to the present day. On 18 November it became the recipient of the 2010 Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction by the Finnish Book Foundation, worth €30,000.

The choice, from six shortlisted works, was made by economist Sinikka Salo. Suomalaiset kapellimestarit: Sibeliuksesta Saloseen, Kajanuksesta Franckiin (‘Finnish conductors: from Sibelius to Salonen, from Kajanus to Franck’) is published by Otava.

The other five works on the shortlist were Itämeren tulevaisuus (‘The future of the Baltic Sea’, Gaudeamus) by Saara Bäck, Markku Ollikainen, Erik Bonsdorff, Annukka Eriksson, Eeva-Liisa Hallanaro, Sakari Kuikka, Markku Viitasalo and Mari Walls; the Finnish Marshal C.G. Mannerheim’s early 20th-century travel diaries, Dagbok förd under min resa i Centralasien och Kina 1906–07–08 (‘Diary from my journey to Central Asia and China 1906–07–08’, Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland & Atlantis), edited by Harry Halén; Vihan ja rakkauden liekit. Kohtalona 1930-luvun Suomi (‘Flames of hatred and love. 1930s Finland as a destiny’, Otava) by Sirpa Kähkönen; Suomalaiset kalaherkut (‘Finnish fish delicacies’, Otava) by Tatu Lehtovaara (photographs by Jukka Heiskanen) and Puukon historia (‘A history of the Finnish puukko knife’, Apali) by Anssi Ruusuvuori.