Search results for "jarkko/2011/04/2010/10/mikko-rimminen-nenapaiva-nose-day"

Success after success

9 March 2012 | This 'n' that

The women of Purge: Elena Leeve and Tea Ista in Sofi Oksanen's Puhdistus at the Finnish National Theatre, directed by Mika Myllyaho. Photo: Leena Klemelä, 2007

Sofi Oksanen’s Purge, an unparalleled Finnish literary sensation, is running in a production by Arcola Theatre in London, from 22 February to 24 March.

First premiered at the Finnish National Theatre in Helsinki in 2007, Puhdistus, to give it its Finnish title, was subsequently reworked by Oksanen (born 1977) into a novel – her third.

Puhdistus retells the story of her play about two Estonian women, moving through the past in flashbacks between 1939 and 1992. Aliide has experienced the horrors of the Stalin era and the deportation of Estonians to Siberia, but has to cope with the guilt of opportunism and even manslaughter. One night in 1992 she finds a young woman in the courtyard of her house; Zara has just escaped from the claws of members of the Russian mafia who held her as a sex slave. (Maya Jaggi reviewed the novel in London’s Guardian newspaper.) More…

Rock or baroque?

30 April 2014 | Extracts, Non-fiction

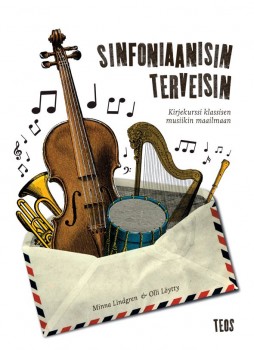

What if your old favourites lose their flavour? Could there be a way of broadening one’s views? Scholar Olli Löytty began thinking that there might be more to music than 1980s rock, so he turned to the music writer Minna Lindgren who was delighted by the chance of introducing him the enormous garden of classical music. In their correspondence they discussed – and argued about – the creativity of orchestra musicians, the significance of rhythm and whether the emotional approach to music might not be the only one. Their letters, from 2009 to 2013, an entertaining musical conversation, became a book. Extracts from Sinfoniaanisin terveisin. Kirjekurssi klassisen musiikin maailmaan (‘With symphonical greetings. A correspondence course in classical music’)

What if your old favourites lose their flavour? Could there be a way of broadening one’s views? Scholar Olli Löytty began thinking that there might be more to music than 1980s rock, so he turned to the music writer Minna Lindgren who was delighted by the chance of introducing him the enormous garden of classical music. In their correspondence they discussed – and argued about – the creativity of orchestra musicians, the significance of rhythm and whether the emotional approach to music might not be the only one. Their letters, from 2009 to 2013, an entertaining musical conversation, became a book. Extracts from Sinfoniaanisin terveisin. Kirjekurssi klassisen musiikin maailmaan (‘With symphonical greetings. A correspondence course in classical music’)

Olli, 19 March, 2009

Dear expert,

I never imagined that the day would come when I would say that rock had begun to sound rather boring. There are seldom, any more, the moments when some piece sweeps you away and makes you want to listen to more of the same. I derive my greatest enjoyment from the favourites of my youth, and that is, I think, rather alarming, as I consider people to be naturally curious beings whom new experiences, extending their range of experiences and sensations, brings nothing but good.

Singing along, with practised wistfulness, to Eppu Normaali’s ‘Murheellisten laulujen maa’ (‘The land of sad songs’) alone in the car doesn’t provide much in the way of inspiration. It really is time to find something new to listen to! My situation is already so desperate that I am prepared to seek musical stimulation from as distant a world as classical music. I know more about the African roots of rock than about the birth of western music, the music that is known as classical. But it looks and sounds like such an unapproachable culture that I badly need help on my voyage of exploration. Where should I start, when I don’t really know anything? More…

In pursuit of a conscience

19 March 2012 | Drama, Fiction

‘An unflinching opera and a hot-blooded cantata about a time when the church was torn apart, Finland was divided and gays stopped being biddable’: this is how Pirkko Saisio’s new play HOMO! (music composed by Jussi Tuurna) is described by the Finnish National Theatre, where it is currently playing to full houses. This tragicomical-farcical satire takes up serious issues with gusto. In this extract we meet Veijo Teräs, troubled by his dreams of Snow White, who resembles his steely MP wife Hellevi – and seven dwarves. Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

Dictators and bishops: Scene 15, ‘A small international gay opera’. Photographs: The Finnish National Theatre / Laura Malmivaara, 2011

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Veijo Teräs

Hellevi, Veijo’s wife and a Member of Parliament

Hellevi’s Conscience

Rebekka, Hellevi and Veijo’s daughter

Moritz, Hellevi and Veijo’s godson

Agnes af Starck-Hare, Doctor of Psychiatry

Seven Dwarves

Tom of Finland

Atik

The Bishop of Mikkeli

Adolf Hitler

Albert Speer

Josef Stalin

Old gays: Kale, Jorma, Rekku, Risto

Olli, Uffe,Tiina, Jorma: people from SETA [the Finnish LGBT association]

Second Lieutenant, Private Teräs, the men in the company

A Policeman

Big Gay, Little Gay, Middle Gay

William Shakespeare

Hermann Göring

Hans-Christian Andersen

Teemu & Oskari, a gay couple

The Apostle Paul

Father Nitro

Winston Churchill

SCENE ONE

On the stage, a narrow closet.

Veijo Teräs appears, struggling to get out of the closet.

Veijo Teräs is dressed as a prince. He is surprised and embarrassed to see that the audience is already there. He seems to be waiting for something.

He speaks, but continues to look out over the audience expectantly.

Snow White's spouse, Veijo (Juha Muje), and the dwarves. Photo: Laura Malmivaara, 2011

VEIJO

This outfit isn’t specifically for me, because… I mean, it’s part of this whole thing. This Snow White thing. I’m waiting for the play to start. Just like you are. My name is Veijo Teräs and I’m playing the point of view role in this story. Writers put point of view roles like this in their plays nowadays. They didn’t use to.

Just to be clear – this isn’t a ballet costume. I’m not going to do any ballet dancing, but I won’t mind if someone dances, even if it’s a man. Particularly if it’s a man. But I don’t watch. Ballet, I mean. Not at the opera house, or on television, or anywhere, and I have no idea why we had to bring up ballet – or I had to bring it up – because this is a historical costume, so it’s appropriate. This is what men used to wear, real men like Romeo and Hamlet, or Cyrano de Bergerac. But we in the theatre these days have a hell of a job getting an audience to listen to what a man has to say when he’s standing there saying what he has to say in an outfit like this. People get the idea that it’s a humorous thing, but this isn’t, this Snow White thing, where I play the prince. Snow White is waiting in her glass casket, she died from an apple, which seems to have become the Apple logo, Lord knows why, the one on the laptops you see on the tables of every café in town. More…

Landscape

30 June 2006 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

(Landskap, 1919). Introduction by Juha Virkkunen

12 March

To begin with, there’s a great white field. The field is criss-crossed with low slender fences and little patches of yellow-green stubble peering up through the snow, and hare-tracks slanting away towards the stubble. But we won’t notice the fences and the stubble and the hare tracks. Because we’re going to take a wider, more sort of decorative view.

So we see the great white field. And where the field ends a dark green screen has been drawn. The screen has been cut short rather amusingly in the middle, so one can see yet another white held. This belongs to another village. And this other village itself has crept up timidly to the forest-clad hill and lies close to it, so we don’t notice this other village. Because we want to take a wider view of things. More…

Daddy dear

30 June 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Vanikan palat (‘Pieces of crispbread’, Otava, 2004). Interview by Soila Lehtonen

Dad’s at the mess again. Comes back some time in the early hours. Clattering, blubbing, clinging to some poem, he collapses in the hall.

We pretend to sleep. It’s not a bad idea to take a little nap. After a quarter of an hour Dad wakes up. Comes to drag us from our beds. Crushes us four sobbing boys against his chest as if he were afraid that a creeping foe intended to steal us. We cry too, of course, but from pain. Four boys belted around a non-commissioned officer is too much. It hurts. And the grip only tightens. Dad whines:

‘Boys, I will never leave you. Dad will never give his boys away. There will be no one who can take you from me.’ More…

Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011

1 December 2011 | In the news

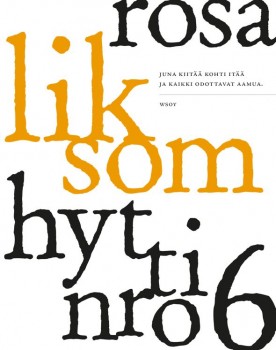

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011, worth €30,000, is Rosa Liksom, for her novel Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY): read translated extracts and an introduction of the author here on this page.

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011, worth €30,000, is Rosa Liksom, for her novel Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY): read translated extracts and an introduction of the author here on this page.

The prize was awarded on 1 December. The winner was selected by the theatre manager Pekka Milonoff from a shortlist of six.

‘Hytti nro 6 is an extraordinarily compact, poetic and multilayered description of a train journey through Russia. The main character, a girl, leaves Moscow for Siberia, sharing a compartment with a vodka-swilling murderer who tells hair-raising stories about his own life and about the ways of his country. – Liksom is a master of controlled exaggeration. With a couple of carefully chosen brushstrokes, a mini-story, she is able to conjure up an entire human destiny,’ Milonoff commented.

Author and artist Rosa Liksom (alias Anni Ylävaara, born 1958), has since 1985 written novels, short stories, children’s book, comics and plays. Her books have been translated into 16 languages.

Appointed by the Finnish Book Foundation, the prize jury (journalist and critic Hannu Marttila, journalist Tuula Ketonen and translator Kristiina Rikman) shortlisted the following novels: Kallorumpu (‘Skull drum’, Teos) by Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, William N. Päiväkirja (‘William N. Diary’, Otava) by Kristina Carlson, Huorasatu (‘Whore tale’, Into) by Laura Gustafsson, Minä, Katariina (‘I, Catherine’, Otava) by Laila Hirvisaari, and Isänmaan tähden (‘For fatherland’s sake’, first novel; Teos) by Jenni Linturi.

Rosa Liksom travelled a great deal in the Soviet Union in the 1980s. She said she hopes that literature, too, could play a role in promoting co-operation between people, cultures and nations: ‘For the time being there is no chance of some of us being able to live on a different planet.’

Best Translated Book Award 2011

13 May 2011 | In the news

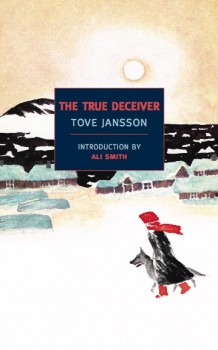

Thomas Teal’s translation from Swedish into English of Tove Jansson’s novel Den ärliga bedragaren (Schildts, 1982), entitled The True Deceiver (published by New York Review Books, 2009), won the 2011 Best Translated Book Award in fiction (worth $5,000; supported by Amazon.com). The winning titles and translators for this year’s awards were announced on 29 April in New York City as part of the PEN World Voices Festival.

Thomas Teal’s translation from Swedish into English of Tove Jansson’s novel Den ärliga bedragaren (Schildts, 1982), entitled The True Deceiver (published by New York Review Books, 2009), won the 2011 Best Translated Book Award in fiction (worth $5,000; supported by Amazon.com). The winning titles and translators for this year’s awards were announced on 29 April in New York City as part of the PEN World Voices Festival.

Organised by Three percent (the link features a YouTube recording from the award ceremony, introducing the translator, Thomas Teal [fast-forward to 7.30 minutes]) at the University of Rochester, and judged by a board of literary professionals, the Best Translated Book Award is ‘the only prize of its kind to honour the best original works of international literature and poetry published in the US over the previous year’. ‘Subtle, engaging and disquieting, The True Deceiver is a masterful study in opposition and confrontation’, said the jury.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001), mother of the Moomintrolls, story-teller and illustrator of children’s books, translated into 40 languages, began to write novels and short stories for adults in her later years. Psychologically sharp studies of relationships, they are written with cool understatement and perception.

Quality writing will work its way into a wider knowledge (i.e. a bigger language and readership) eventually… even though occasionally it may seem difficult to know where exactly it comes from; in a review published in the London Guardian newspaper, the eminent writer Ursula K. Le Guin assumed Tove Jansson was Swedish.

Government Prize for Translation 2011

24 November 2011 | In the news

María Martzoúkou. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

The Finnish Government Prize for Translation of Finnish Literature of 2011 – worth € 10,000 – was awarded to the Greek translator and linguist María Martzoúkou.

Martzoúkou (born 1958), who lives in Athens, where she works for the Finnish Institute, has studied Finnish language and literature as well as ancient Greek at the Helsinki University, where she has also taught modern Greek. She was the first Greek translator to publish translations of the Finnish epic, the Kalevala: the first edition, containing ten runes, appeared in 1992, the second, containing ten more, in 2004.

‘Saarikoski was the beginning,’ she says; she became interested in modern Finnish poetry, in particular in the poems of Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983). As Saarikoski also translated Greek literature into Finnish, Martzoúkou found herself doubly interested in his works.

Later she has translated poetry by, among others, Tua Forsström, Paavo Haavikko, Riina Katajavuori, Arto Melleri, Annukka Peura, Pentti Saaritsa, Kirsti Simonsuuri and Caj Westerberg.

Among the Finnish novelists Martzoúkou has translated are Mika Waltari (five novels; the sixth, Turms kuolematon, The Etruscan, is in the printing press), Väinö Linna (Tuntematon sotilas, The Unknown Soldier) and Sofi Oksanen (Puhdistus, Purge).

María Martzoúkou received her award in Helsinki on 22 November from the minister of culture and sports, Paavo Arhinmäki. Thanking Martzoúkou for the work she has done for Finnish fiction, he pointed out that The Finnish Institute in Athens will soon publish a book entitled Kreikka ja Suomen talvisota (‘Greece and the Finnish Winter War’), a study of the relations of Finland and Greece and the news of the Winter War (1939–1940) in the Greek press, and it contains articles by Martzoúkou.

The prize has been awarded – now for the 37th time – by the Ministry of Education and Culture since 1975 on the basis of a recommendation from FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange.

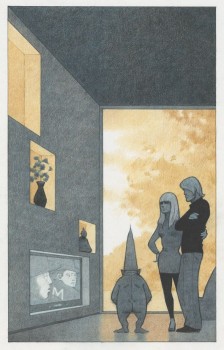

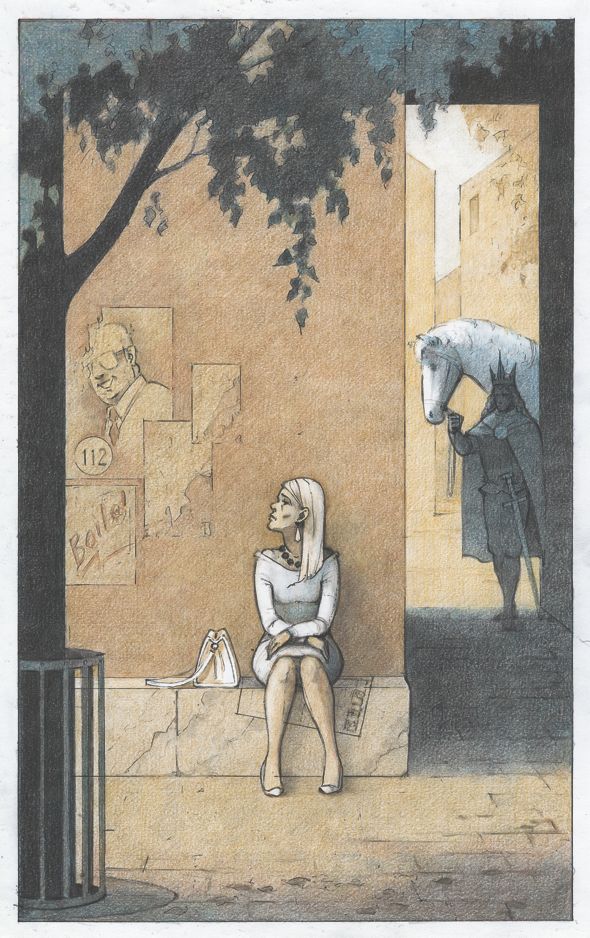

Picture this

Accompanied by one or two sentences of the most gnomic kind, architect Mikko Metsähonkala’s illustrations speak volumes. The picture-stories in his book Toisaalta / (P)å andra sidan / In Other Wor(l)ds blend the real and the surreal using fairy tales, references to historical or fictional characters and episodes from everyday life.

Accompanied by one or two sentences of the most gnomic kind, architect Mikko Metsähonkala’s illustrations speak volumes. The picture-stories in his book Toisaalta / (P)å andra sidan / In Other Wor(l)ds blend the real and the surreal using fairy tales, references to historical or fictional characters and episodes from everyday life.

(The Finnish composer Lauri Supponen was inspired by Metsähonkala’s ‘humaphone’ – see below –, and his composition The Dordrecht Humaphone was first performed at the Cheltenham Festival, England, in 2012, to favourable reviews.) More…

Coming up…

11 April 2013 | This 'n' that

Illustration: Mikko Metsähonkala

‘Just before the meeting Ludwig chickened out. In the ad he had bragged that he was a “sporty male with a sense of humour”. Would Patsy accept his illiteracy, brutal table manners and cruelty towards the peasants?’

One picture, few words: Mikko Metsähonkala’s artwork creates a moment in a universe – recognisable or completely strange – providing it with a laconic textual subtext. We feature some of his stories published in Toisaalta / (P)å andra sidan / In Other Wor(l)ds.

Helsinki Book Fair 2011

2 November 2011 | In the news

President Toomas Hendrik Ilves at the Book Fair: Viro is Estonia in Finnish. Photo: Kimmo Brandt/The Finnish Fair Corporation

The Helsinki Book Fair, held from 27 to 30 October, attracted more visitors than ever before: 81,000 people came to browse and buy books at the stands of nearly 300 exhibitors and to meet more than a thousand writers and performers at almost 700 events.

The Music Fair, the Wine, Food and Good Living event and the sales exhibition of contemporary art, ArtForum, held at the same time at Helsinki’s Exhibition and Convention Centre, expanded the selection of events and – a significant synergetic advantage, of course – shopping facilities. Twenty-eight per cent of the visitors thought this Book Fair was better than the previous one held in 2010.

According to a poll conducted among three hundred visitors, 21 per cent had read an electronic book while only 6 per cent had an e-book reader of their own. Twenty-five per cent did not believe that e-books will exceed the popularity of printed books, and only three per cent believed that e-books would win the competition.

Estonia was the theme country this time. President Toomas Hendrik Ilves of the Republic of Estonia noted in his speech at the opening ceremony: ‘As we know well from the fate of many of our kindred Finno-Ugric languages, not writing could truly mean a slow national demise. So publish or perish has special meaning here. Without a literary culture, we would simply not exist and we have known this for many generations, since the Finnish and Estonian national epics Kalevala and Kalevipoeg. – During the last decade, more original literature and translations have been published in Estonia than ever before. And we need only access the Internet to glimpse the volume of text that is not printed – it is even larger than the printed corpus. We live in an era of flood, not drought, and thus it is no wonder that as a discerning people, we do not want to keep our ideas and wisdom to ourselves but try to share and distribute them more widely. The idea is not to try to conquer the world but simply, with our own words, to be a full participant in global literary culture, and in the intellectual history and future of humankind.’

Finland meets Estonia: authors Sofi Oksanen and Viivi Luik in discussion. Photo: Kimmo Brandt/The Finnish Fair Corporation

Cityscapes

23 February 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Photographer Stefan Bremer’s home town, Helsinki, provides endless inspiration, material and atmospheric. For forty years Bremer has been recording views of the maritime city, its changing seasons, its cultural events, its people. These images are from his new book – entitled, simply, Helsinki (Teos, 2012)

City kids: day-care outing in Töölönlahti park. Photo: Stefan Bremer, 2010

When I was a child, Helsinki seemed to me a grey and sad town. Stooping, quiet people walked its broad streets. The colours of the houses had been darkened by coal smoke over the years, and new buildings were coated a depressing grey.

A lot has since changed. Today, Helsinki is younger than it was in my youth. More…

Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2010

19 November 2010 | In the news

A massive tome running to 1,000 pages by Vesa Sirén, journalist and music critic of the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper, features Finnish conductors from the 1880s to the present day. On 18 November it became the recipient of the 2010 Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction by the Finnish Book Foundation, worth €30,000.

A massive tome running to 1,000 pages by Vesa Sirén, journalist and music critic of the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper, features Finnish conductors from the 1880s to the present day. On 18 November it became the recipient of the 2010 Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction by the Finnish Book Foundation, worth €30,000.

The choice, from six shortlisted works, was made by economist Sinikka Salo. Suomalaiset kapellimestarit: Sibeliuksesta Saloseen, Kajanuksesta Franckiin (‘Finnish conductors: from Sibelius to Salonen, from Kajanus to Franck’) is published by Otava.

The other five works on the shortlist were Itämeren tulevaisuus (‘The future of the Baltic Sea’, Gaudeamus) by Saara Bäck, Markku Ollikainen, Erik Bonsdorff, Annukka Eriksson, Eeva-Liisa Hallanaro, Sakari Kuikka, Markku Viitasalo and Mari Walls; the Finnish Marshal C.G. Mannerheim’s early 20th-century travel diaries, Dagbok förd under min resa i Centralasien och Kina 1906–07–08 (‘Diary from my journey to Central Asia and China 1906–07–08’, Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland & Atlantis), edited by Harry Halén; Vihan ja rakkauden liekit. Kohtalona 1930-luvun Suomi (‘Flames of hatred and love. 1930s Finland as a destiny’, Otava) by Sirpa Kähkönen; Suomalaiset kalaherkut (‘Finnish fish delicacies’, Otava) by Tatu Lehtovaara (photographs by Jukka Heiskanen) and Puukon historia (‘A history of the Finnish puukko knife’, Apali) by Anssi Ruusuvuori.