Search results for "sofi oksanen/feed/www.booksfromfinland.fi/2012/04/2010/10/riikka-pulkkinen-totta-true"

Make or break?

17 November 2011 | This 'n' that

Two tax collectors: anonymous painter, after Marinus van Reymerswaele (ca. 1575–1600). Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy. Wikimedia

In Finland, tax returns are public information. So, every November the media publish lists of the top earners in Finland, dividing them into the categories of earned and investment income. Every November it is revealed who are millionaires and who are just plain rich.

The Taloussanomat (‘The economic news’) newspaper offers a list (Finnish only) of the 5,000 people who earned most last year (in terms of both earned and investment income, together with the proportion of income they have paid in tax). You can also search lists of various status and professions: rock/pop stars, media, sports, MPs, celebrities, politicians of various political parties…

So let’s take a look at Taloussanomat’s selected list of authors: number one is the celebrity author Jari Tervo (309,971 euros, tax percentage 45); number two, the internationally famous Sofi Oksanen (302,634 euros, 46 per cent); the next two are Sinikka Nopola, writer of children’s books, (264,000) and Arto Paasilinna (262,300; now after an illness, retired as a writer), translated into more than 30 languages since the 1970s. (The film critic and author Peter von Bagh made almost 900,000 euros – not by writing books, but by selling his share of a music company to an international enterprise.)

As tax data are public in Finland, there’s vigorous and decidedly informed public debate on how much money, for example, directors of public pension institutions and government offices or ministers and other top politicians are paid, and how much they should be paid: what is equitable, what is reasonable? A million dollar question indeed…

Among the European Union countries, it is only in Finland, Sweden and Denmark that there is no universal minimum wage. Here, wages are determined in trade wage negotiations. The average monthly salary in the private sector in 2010 was approximately 3,200 euros. In contrast to that, Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo, the Nokia CEO and President, who tops the 2010 tax list, earned a salary of 8 million last year, because – and precisely because – he was sacked (and replaced by the Irishman Steven Elop).

The CIA’s Gini index measures the degree of inequality in the distribution of family income in a country. The more unequal a country’s income distribution, the higher is its Gini index. The country with the highest number is Sweden, 23; the lowest, South Africa, 65 (data from both, 2005). Finland’s figure is 26.8 (2008), Germany 27 (2006), the European Union’s 34. The United Kingdom stands at 34 (2005), and the USA at 45 (2007). The figure in Finland seems to be on the rise though, as the figure back in 1991 was 25.6.

There’s been plenty of research and debate on economic inequality and the ways it harms societies. This link takes you to a fascinating video lecture (July 2011 – now seen by almost half a million people) by Richard Wilkinson, British author, Profefssor Emeritus of social epidemiology.

European Union literature prizes 2010

8 October 2010 | In the news

Riku Korhonen. Photo: Harri Pälviranta

With his novel Lääkäriromaani (‘Doctor novel’, Sammakko, 2009), Riku Korhonen (born 1972) is one of the 11 winners of the 2010 European Union Prize for Literature, worth €5,000 each. The winners were announced at Frankfurt Book Fair on 6 October.

The European Commission, the European Booksellers’ Federation (EBF), the European Writers’ Council (EWC) and the Federation of European Publishers (FEP) award the annual prize, which is supported through the European Union’s culture programme. It aims to draw attention to new talents and to promote the publication of their books in different countries, as well as celebrating European cultural diversity. Authors who have published two to four prose works during the last five years and whose work has been translated into two foreign languages at the most are eligible for the prize.

Korhonen has published two novels, a collection of short prose and a collection of poetry. Read translated extracts, published in Books from Finland in 2003, from his first novel, Kahden ja yhden yön tarinoita (‘Tales from two and one nights’, 2003) here. More…

Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2010

19 November 2010 | In the news

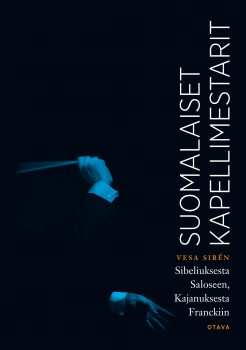

A massive tome running to 1,000 pages by Vesa Sirén, journalist and music critic of the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper, features Finnish conductors from the 1880s to the present day. On 18 November it became the recipient of the 2010 Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction by the Finnish Book Foundation, worth €30,000.

A massive tome running to 1,000 pages by Vesa Sirén, journalist and music critic of the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper, features Finnish conductors from the 1880s to the present day. On 18 November it became the recipient of the 2010 Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction by the Finnish Book Foundation, worth €30,000.

The choice, from six shortlisted works, was made by economist Sinikka Salo. Suomalaiset kapellimestarit: Sibeliuksesta Saloseen, Kajanuksesta Franckiin (‘Finnish conductors: from Sibelius to Salonen, from Kajanus to Franck’) is published by Otava.

The other five works on the shortlist were Itämeren tulevaisuus (‘The future of the Baltic Sea’, Gaudeamus) by Saara Bäck, Markku Ollikainen, Erik Bonsdorff, Annukka Eriksson, Eeva-Liisa Hallanaro, Sakari Kuikka, Markku Viitasalo and Mari Walls; the Finnish Marshal C.G. Mannerheim’s early 20th-century travel diaries, Dagbok förd under min resa i Centralasien och Kina 1906–07–08 (‘Diary from my journey to Central Asia and China 1906–07–08’, Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland & Atlantis), edited by Harry Halén; Vihan ja rakkauden liekit. Kohtalona 1930-luvun Suomi (‘Flames of hatred and love. 1930s Finland as a destiny’, Otava) by Sirpa Kähkönen; Suomalaiset kalaherkut (‘Finnish fish delicacies’, Otava) by Tatu Lehtovaara (photographs by Jukka Heiskanen) and Puukon historia (‘A history of the Finnish puukko knife’, Apali) by Anssi Ruusuvuori.

Jarl Hellemann in memoriam 1920–2010

15 March 2010 | In the news

One of the grand old men of Finnish publishing, Jarl Hellemann, wrote in one of his own books: ‘Book publishing is by nature personified, a personal activity.

‘Most of the world’s old publishing houses still bear their founders’ names: Bonnier, Collins, Heinemann, Harper, Knopf, Bertelsmann, Werner Söderström, Gummerus. Americans ignorant of the exceptions to this rule among Finnish publishers still occasionally begin their letters, “Dear Mr Otava” or “Dear Mr Tammi”.’ (From Kustantajan näkökulma, ‘A publisher’s point of view’, Otava, published in Books from Finland 3/1999)

Hellemann himself was Mr Tammi for a long time; he started as a publishing editor at Tammi Publishing Company in 1945 and retired as managing director in 1982.

In 1955 he founded Keltainen kirjasto, the ‘Yellow Library’, an imprint of novels published since the First World War by prominent writers from all over the world. The first was Too Late the Phalarope by Alan Paton, the latest – published in 2009 – was The Disappeared by Kim Echlin. The series now contains more than 400 works, among them novels by 24 Nobel prize-winners.

Among the books in Keltainen kirjasto (list, in Finnish), Hellemann’s favourite was James Joyce’s Ulysses, translated by the poet and author Pentti Saarikoski in 1964. Hellemann continued choosing books for Keltainen kirjasto long after he retired.

Born in Copenhagen, Hellemann moved with his family to his mother’s home country, Finland, in the 1930s. Well-travelled and fluent in many languages, Hellemann himself published a novel (at the age of 25), three books on publishing and, in 1996, his memoirs.

Our favourite things

29 January 2010 | Letter from the Editors

Every reader has his or her favourite book. It is possible to define, with acceptable criteria, when a work of fiction is ‘a good novel’: do the plot, characterisation and language work, does it have anything to say? But when is a ‘good’ novel better than another ‘good’ novel? More…

Elina Brotherus & Riikka Ala-harja

The passing of time

2 March 2015 | Extracts, Fiction, Prose

In 1999 the Musée Nicéphore Niépce invited the young Finnish photographer Elina Brotherus to Chalon-sur-Saône in Burgundy, France, as a visiting artist.

After initially qualifying as an analytical chemist, Brotherus was then at the beginning of her career as a photographer. Everything lay before her, and she charted her French experience in a series of characteristically melancholy, subjective images.

Twelve years on, she revisited the same places, photographing them, and herself, again. The images in the resulting book, 12 ans après / 12 vuotta myöhemmin / 12 years later (Sémiosquare, 2015) are accompanied by a short story by the writer Riikka Ala-Harja, who moved to France a little later than Brotherus.

In the event, neither woman’s life took root in France. The book represents a personal coming-to-terms with the evaporation of youthful dreams, a mourning for lost time and broken relationships, a level and unselfpitying gaze at the passage of time: ‘Life has not been what I hoped for. Soon it will be time to accept it and mourn for the dreams that will never come true. Mourn for the lost time, my young self, who no longer exists.’

1999 Mr Cheval’s nose

Stories in the stone

2 December 2010 | Extracts, Non-fiction

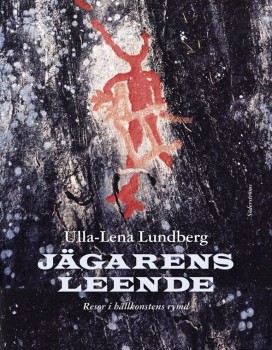

Extracts from Jägarens leende. Resor in hällkonstens rymd (‘Smile of the hunter. Travels in the space of rock art’, Söderströms, 2010)

‘Why do some people choose to expend what is often a great deal of effort hammering images in the bedrock itself, while others conjure up, in the blink of an eye, brilliantly radiant pictures on a rock-face that was empty yesterday but is now peopled by mythological animals, spirits and shamans?

‘Why do some people choose to expend what is often a great deal of effort hammering images in the bedrock itself, while others conjure up, in the blink of an eye, brilliantly radiant pictures on a rock-face that was empty yesterday but is now peopled by mythological animals, spirits and shamans?

‘I think about this often – I who love painting but who still chose a career that involves me sitting and hammering away, day in and day out, like a true rock-carver,’ writes author and ethnologist Ulla-Lena Lundberg in her new book on the art of the primeval man

When the children of Israel went into Babylonian captivity, hanging up their harps on the willow-trees and weeping as they remembered Zion, my sister and I were already sitting by the rivers of Babylon. We knew how they felt. Our father was dead and we had been sent away from our home. We sat there clinging to each other, or rather I was the one clinging to Gunilla, and she had to try to rouse herself and find something for us to do, to give us something else to think about. More…

Hip hip hurray, Moomins!

22 October 2010 | This 'n' that

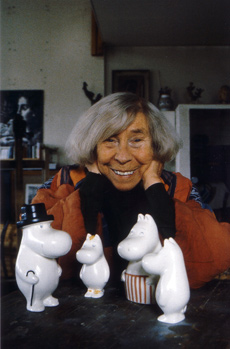

Partying in Moomin Valley: Moomintroll (second from right) dancing through the night with the Snork Maiden (from Tove Jansson’s second Moomin book, Kometjakten, Comet in Moominland, 1946)

The Moomins, those sympathetic, rotund white creatures, and their friends in Moomin Valley celebrate their 65th birthday in 2010.

Tove Jansson published her first illustrated Moomin book, Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen (‘The little trolls and the big flood’) in 1945. In the 1950s the inhabitants of Moomin Valley became increasingly popular both in Finland and abroad, and translations began to appear – as did the first Moomin merchandise in the shops.

Jansson later confessed that she eventually had begun to hate her troll – but luckily she managed to revise her writing, and the Moomin books became more serious and philosophical, yet retaining their delicious humour and mild anarchism. The last of the nine storybooks, Moominvalley in November, appeared in 1970, after which Jansson wrote novels and short stories for adults.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001) was a painter, caricaturist, comic strip artist, illustrator and author of books for both children and adults. Her Moomin comic strips were published in the daily paper the London Evening News between 1954 and 1974; from 1960 onwards the strips were written and illustrated by Tove’s brother Lars Jansson (1926–2000).

Tove’s niece, Sophia Jansson (born 1962) now runs Moomin Characters Ltd as its artistic director and majority shareholder. (The company’s latest turnover was 3,6 million euros).

For the ever-growing fandom of Jansson there is a delightful biography of Tove (click ‘English’) and her family on the site, complete with pictures, video clips and texts.

The world now knows Moomins; the books have been translated into 40 languages. The London Children’s Film Festival in October 2010 featured the film Moomins and the Comet Chase in 3D, with a soundtrack by the Icelandic artist Björk. An exhibition celebrating 65 years of the Moomins (from 23 October to 15 January 2011) at the Bury Art Gallery in Greater Manchester presented Jansson’s illustrations of Moominvalley and its inhabitants.

In association with several commercial partners in the Nordic countries Moomin Characters launched a year-long campaign collecting funds to be donated to the World Wildlife Foundation for the protection of the Baltic Sea. Tove Jansson lived by the Baltic all her life – she spent most of her summers on a small barren island called Klovharu – and the sea featured strongly in her books for both children and adults.

Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2012

5 December 2012 | In the news

‘It is one of the rules of quality journalism that writers aim for even-handed and impartial reporting, but at the same time challenge their respondents to account for their actions. Writers should also have the capacity for in-depth reporting and analysis,’ said Janne Virkkunen, former Editor-in-Chief of Helsingin Sanomat newspaper on 8 November, as he announced the winner of this year’s Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction, worth €30,000.

‘It is one of the rules of quality journalism that writers aim for even-handed and impartial reporting, but at the same time challenge their respondents to account for their actions. Writers should also have the capacity for in-depth reporting and analysis,’ said Janne Virkkunen, former Editor-in-Chief of Helsingin Sanomat newspaper on 8 November, as he announced the winner of this year’s Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction, worth €30,000.

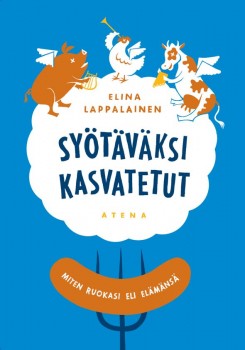

The winner, Syötäväksi kasvatetut. Miten ruokasi eli elämänsä (‘Grown to be eaten. How your food lived its life’, Atena) by the young journalist Elina Lappalainen, is her first book.

‘The book could have fallen prey to the sensationalism of which we all probably have experience in the media, at least. This writer was able to avoid the temptation,’ Janne Virkkunen said.

The other works on the shortlist of six were as follows: Arabikevät (‘The Arab spring’, Avain), a study of spring 2011 in the Arab world by Lilly Korpiola and Hanna Nikkanen, Norsusta nautilukseen. Löytöretkiä eläinkuvituksen historiaan (‘From the elephant to the nautilus. Explorations into the illustration of animals’, John Nurminen Foundation) by Anto Leikola, Kevyt kosketus venäjän kieleen (‘A light touch to the Russian language’, Gaudeamus) by professor of Russian Arto Mustajoki, Karhun kainalossa. Suomen kylmä sota 1947–1990 (‘Under the arm of the Bear. Finland’s Cold War 1947–1990’, Otava) by Jukka Tarkka and Markkinat ja demokratia. Loppu enemmistön tyrannialle (‘Market and democracy. The end of the tyranny of the majority’, Otava) by banker Björn Wahlroos.

The novel that won: the Runeberg Prize 2012

9 February 2012 | In the news

Katja Kettu. Photo: WSOY

The Runeberg Prize for fiction, awarded this year for the twenty-sixth time, went to Katja Kettu for her third novel, Kätilö (‘The midwife’, WSOY).

Kettu (born 1978) is a writer and director of animated films. The prize, worth €10,000, was awarded on 5 February – the birthday of the poet J.L Runeberg (1804–1877) – in the southern Finnish city of Porvoo.

The jury – representing the prize’s founders, the Uusimaa newspaper, the city of Porvoo, both the Finnish and Finland-Swedish writers’ associations and the Finnish Critics’ Association – chose the winner from a shortlist of eight books. The jury was particularly impressed by the rich language of Kettu’s novel, set in the Lapp War of 1944–45, and the colourful portrayal of the characters.

The other seven finalists were a collection of essays and poems, Magnetmemoarerna, by Ralf Andtbacka (‘Magnet memoirs’, Ellips), the novel Tusenblad, en kvinna som snubblar (‘Millefeuille, the woman who stumbles’, Schildts), the novel Gisellen kuolema (‘Giselle’s death’, Robustos) by Siiri Eloranta, two collections of poems, Aallonmurtaja (‘The breakwater’, Otava) by Pauliina Haasjoki and De bronsblå solarna (‘The bronze-blue suns’, Söderströms) by Kurt Högnäs, a collection of short stories by Joni Pyysalo, entitled Ja muita novelleja (‘And other stories’, WSOY) and the novel Paljain käsin (‘With bare hands’, Gummerus) by Essi Tammimaa.

Damned nihilists

30 December 2008 | Extracts, Non-fiction

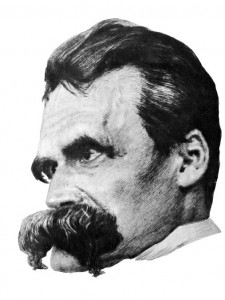

Much misunderstood: father of the superman, Friedrich Nietzsche.

The term nihilism is often bandied about, but often badly misunderstood. In extracts from his new book, Ei voisi vähempää kiinnostaa. Kirjoituksia nihilismistä (‘Couldn’t care less. Writings on nihilism’, Atena, 2008), the social scientist and philosopher Kalle Haatanen discusses the true legacy of Friedrich Nietzsche, nihilism’s high priest

The word nihilist is derived from the Latin: ‘nihil’ means, simply, ‘nothing’. When someone is labelled as nihilist or seen as representing nihilism, this has always been a curse, a mockery or an accusation, whether in philosophy, politics or everyday conversation. More recently, the word has generally been used to refer to people who do not believe in anything – people whose world-view is without principle, without ideals, barren. More…

Comics turns

16 April 2010 | In the news

Comics make frequent appearances on the lists of best-selling Finnish books: on the ‘What Finland reads’ list in March, Pertti Jarla’s new comic strip book, Fingerpori 3, about the eponymous, weird city of Fingerpori (‘Fingerborg’), is number one. His two other Fingerpori books are number eight and ten on the list. The zany comedy in them is verbal, based on puns – and therefore not easily exportable.

The new and final volume of Hannu Väisänen’s autobiographical, fictional trilogy about the young wannabe artist Antero, Kuperat ja koverat (‘Convex and concave’) made its way into the top ten right away, making its appearance at number two.

The Finlandia Prize -winning novel, Gå inte ensam ut i natten (‘Don’t go out into the night alone’, translated into Finnish as Älä käy yöhön yksin) by Kjell Westö, is number three – the novel was published in September 2009, and this reappearance is partly explained by special campaigns in the bookstores, says Westö’s publisher, Otava.

Sofi Oksanen’s prize-winning novel Puhdistus (Purge, now published in English) from 2008, is back on the list again, now at number four. Kari Hotakainen’s latest novel, Ihmisen osa (‘Human lot’, 2009, to appear in English in 2012) is at number six.

The books that sold

21 February 2013 | In the news

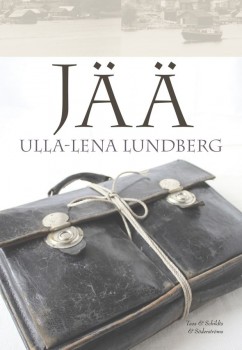

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2012, Ulla-Lena Lundberg’s novel Is (‘Ice’), also turned out to be the winner of the ‘Shadow Finlandia’ prize of the Academic Bookstore in Helsinki. The novel, set on the Åland islands in postwar years, was simultaneously published in Finnish as Jää. This book trade prize is awarded to the best-selling title of the six finalists on the Finlandia Prize list.

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2012, Ulla-Lena Lundberg’s novel Is (‘Ice’), also turned out to be the winner of the ‘Shadow Finlandia’ prize of the Academic Bookstore in Helsinki. The novel, set on the Åland islands in postwar years, was simultaneously published in Finnish as Jää. This book trade prize is awarded to the best-selling title of the six finalists on the Finlandia Prize list.

The best-selling Finnish debut work in the Academic Bookstore was Nälkävuosi (‘The hunger year’, Siltala) by Aki Ollikainen.

Also number one on the December list of best-selling Finnish fiction titles compiled by the Finnish Booksellers’ Association was Lundberg’s novel – in its Finnish translation; the original Swedish-language book came number ten on the same list.

Number two was Sofi Oksanen’s new novel set in Estonia, Kun kyyhkyset katosivat (‘When the doves disappeared’, Like), and number three the hilarious graphic story, Piitles. Tarina erään rockbändin alkutaipaleesta (‘Beatles. The story of the first stage of a rock band’, Otava), by Mauri Kunnas who has written and illustrated dozens of children’s books.

In first and second place on the translated fiction list were J.K. Rowling and J.R.R. Tolkien (The Casual Vacancy, The Hobbit or There and Back Again).

Children chose Finnish books in December – or rather their parents did, buying them as Christmas presents – for the first four places were taken by popular writers such as Sinikka and Tiina Nopola, Aino Havukainen & Sami Toivonen, Mauri Kunnas (Piitles is for mums and dads, not kids!) and Timo Parvela.

On the non-fiction list there was a selection of world record books, cookbooks and biographies – not unusual, considering the season – but number one was Kaiken käsikirja (‘Handbook of everything’) by astronomer and popular writer Esko Valtaoja. A present for all occasions, then?