Search results for "sofi oksanen/feed/www.booksfromfinland.fi/2012/04/tuomas-kyro-mielensapahoittaja-ja-ruskea-kastike-taking-offence-brown-sauce"

Rainer Knapas: Kunskapens rike. Helsingfors universitetsbibliotek – Nationalbiblioteket 1640–2010 [In the kingdom of knowledge. Helsinki University Library – National Library of Finland 1640–2010]

9 August 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kunskapens rike. Helsingfors universitetsbibliotek – Nationalbiblioteket 1640–2010

Kunskapens rike. Helsingfors universitetsbibliotek – Nationalbiblioteket 1640–2010

Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 2012. 462 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-583-244-3

€54, hardback

Tiedon valtakunnassa. Helsingin yliopiston kirjasto – Kansalliskirjasto 1640–2010

[In the kingdom of knowledge. Helsinki University Library – National Library of Finland 1640–2010]

Suomennos [Finnish translation by]: Liisa Suvikumpu

Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2012. 461 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-272-5

€54, hardback

The National Library of Finland was founded in 1640 as the library of Turku Academy. In 1827 it was destroyed by fire: only 828 books were preserved. In 1809 Finland was annexed from Sweden by Russia, and the collection was moved to the new capital of Helsinki, where it formed the basis of the University Library. The neoclassical main building designed by Carl Ludwig Engel is regarded as one of Europe’s most beautiful libraries and was completed in 1845, with an extension added in 1906. Its collections include the Finnish National Bibliography, an internationally respected Slavonic Library, the private Monrepos collection from 18th-century Russia, and the valuable library of maps compiled by the arctic explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld. Renamed in 2006 as Kansalliskirjasto – the National Library of Finland – this institution, which is open to general public, now contains a collection of over three million volumes as well as a host of online services. This beautifully illustrated book by historian and writer Rainer Knapas provides an interesting exposition of the library’s history, the building of its collections and building projects, and also a lively portrait of its talented – and sometimes eccentric – librarians.

Translated by David McDuff

Fatherlands, mother tongues?

12 April 2013 | Letter from the Editors

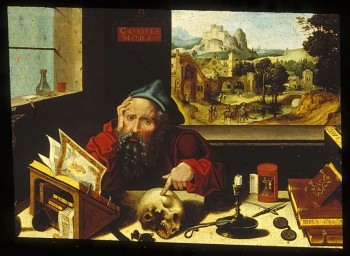

Patron saint of translators: St Jerome (d. 420), translating the Bible into Latin. Pieter Coecke van Aelst, ca 1530. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Photo: Wikipedia

Finnish is spoken mostly in Finland, whereas English is spoken everywhere. A Finnish writer, however, doesn’t necessarily write in any of Finland’s three national languages (Finnish, Swedish and Sámi).

What is a Finnish book, then – and (something of particular interest to us here at the Books from Finland offices) is it the same thing as a book from Finland? Let’s take a look at a few examples of how languages – and fatherlands – fluctuate.

Hannu Rajaniemi has Finnish as his mother tongue, but has written two sci-fi novels in English, which were published in England. A Doctor in Physics specialising in string theory, Rajaniemi works at Edinburgh University and lives in Scotland. His books have been translated into Finnish; the second one, The Fractal Prince / Fraktaaliruhtinas (2012) was in March 2013 on fifth place on the list of the best-selling books in Finland. (Here, a sample from his first book, The Quantum Thief, 2011, Gollancz.)

Emmi Itäranta, a Finn who lives in Canterbury, England, published her first novel, Teemestarin tarina (‘The tea master’s book’, Teos, 2012), in Finland. She rewrote it in English and it will be published as Memory of Water in England, the United States and Australia (HarperCollins Voyager) in 2014. Translations into six other languages will follow. More…

Ulla-Lena Lundberg: Is [Ice]

1 November 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Is

Is

[Ice]

Helsingfors: Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 364 p.

ISBN 978-951-52-2987-8

€ 23.25, hardback

Finnish translation:

Jää

Helsinki: Teos & Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 365 p.

Suomennos [Translated by]: Leena Vallisaari

ISBN 978-951-851-475-9

€ 28.40, hardback

Ulla-Lena Lundberg (born on the island of Kökar, Åland, 1947) is already the author of an extensive list of award-winning books, but her new novel Is (‘Ice’) is undoubtedly her most impressive work. It is written in a classic genre, an epic bound by time and place, in which the sensitive portrayal of characters and details takes a strongly ethical direction. Is describes life in a outer archipelago in the late 1940s, where a young priest arrives with his small family. In his calling he is a man devoted to the Word: helpful, friendly, naïvely unsuspecting in his philanthropy. His wife is cast in a different mould: a practical, at times apparently emotionless survivor, who runs a large household single-handed. The couple becomes part of the community of small islands and its harsh living conditions. At times the ice that shuts the island off from the outside world melts into freedom, only to lapse again into a cold that rudely limits human destinies. Barren nature and a community spirit reverting to early Christianity take the measure of each other in the novel’s dramatic events.

Translated by David McDuff

Elina Lappalainen: Syötäväksi kasvatetut. Miten ruokasi eli elämänsä [Bred for the table. How your food lived its life]

8 February 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Syötäväksi kasvatetut. Miten ruokasi eli elämänsä

Syötäväksi kasvatetut. Miten ruokasi eli elämänsä

[Bred for the table. How your food lived its life]

Jyväskylä: Atena, 2012. 355 p, ill.

ISBN 978-951-796-843-0

€ 29, paperback

The development of animal welfare depends not only on producers, legislation and control, but also on the preferences of central trading and consumers. In her first book, young journalist Elina Lappalainen describes the conditions in which pigs, cattle and chickens live in Finland before they end up on the table. The living conditions for these are on average better than in many other countries, but they are still often poor. For example, it is difficult to build poultry farms of thousands of chickens, and it matters whether the birds live in cages, are organically grown or a deep litter system is used. Large-scale production does not necessarily mean that pigs, for example, are worse off than they would have been formerly on a small pig farm. On average, the best conditions are provided for cattle, though even most of those spend the long winter in a stanchion barn. Lappalainen has written a thoroughly researched, interesting and balanced review of this internationally important and even emotionally sensitive issue. The book was awarded the prestigious Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2012.

Translated by David McDuff

Valokuva taiteeksi. Photography into Art. Hannula & Hinkka -kokoelma / Collection

30 May 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Valokuva taiteeksi. Photography into Art. Hannula & Hinkka -kokoelma / Collection

Valokuva taiteeksi. Photography into Art. Hannula & Hinkka -kokoelma / Collection

Toimituskunta [Edited by] Erja Hannula, Jorma Hinkka, Sofia Lahti, Tuomo-Juhani Vuorenmaa

English translation: Jüri Kokkonen

Helsinki: Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture, Aalto ARTS Books (Musta Taide 4/2012; publication series of The Finnish Museum of Photography 44.) 209 p., ill.

ISBN 958-952-292-000-3

€33.90, hardback

It has been typical of Finland that it lacks collections of international photography, private or public. In the politically turbulent 1970s interest in photography began to grow. The Hippolyte Gallery, run by artist Ismo Kajander, exhibited international photography by Diane Arbus, Eugène Atget and Édouard Boubat, among others. The graphic designer Jorma Hinkka (also Art Director of Books from Finland, 1998–2006) began making posters for Hippolyte ‘out of pure enthusiasm’, and designing books by Finnish photographers, among them Pentti Sammallahti, Ismo Hölttö, Jorma Puranen and Merja Salo. As a result of spending so much time with ‘the black art’ (as it was called by a Finnish pioneer of photography, I.K. Inha, in 1908), Hinkka and his art director spouse Erja Hannula began to collect samples of it. After 30 years, in 2012, they donated more than two hundred photographs by almost a hundred artists to The Finnish Museum of Photography. The social status of the black art has risen considerably since the 1970s, as has professionalism in the field. This book presents excellent reproductions of the collection of photos, taken within a century and a half; the variety of styles and subjects chosen surprise with its richness.

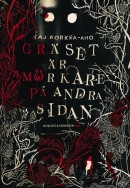

Kaj Korkea-Aho: Gräset är mörkare på andra sidan [The grass is darker on the other side]

9 November 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Gräset är mörkare på andra sidan

Gräset är mörkare på andra sidan

[The grass is darker on the other side]

Helsingfors: Schildts & Söderströms, 2012, 425 p.

ISBN 978-951-52-2999-1

€22.40, hardback

Finnish translation:

Tummempaa tuolla puolen

Helsinki: Teos & Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 436 p.

Suomennos [Translated by]: Laura Beck

ISBN 978-951-851-482-7

€28.40, hardback

Benjamin’s life is turned upside down when he, in despair over his fiancée’s death, discovers things he perhaps didn’t want to know. A photograph taken by a speed camera minutes before the car crash shows that Sofie wasn’t alone in the car. A group of childhood friends reunite for Sofie’s funeral; dark secrets from the past which had until now lain hidden away and unexplained start to come out. What really happened when one of the villagers died in mysterious circumstances? Who murdered little Sidrid Ask? The enormous dark shadow filling people with chilling terror – is it Raamt, evil himself, walking amongst them again? Which should they be more scared of, the supernatural evil or the everyday and human that seems to be all around them? In his second novel the former television presenter and comedian Kaj Korkea-aho (born 1983) writes with great detail and a finely tuned ability to pitch his language. His novel is filled with fear, evil and supernatural phenomena, but at the same time with humour and warmth. The intrigue advances at an addictively fast pace. Korkea-aho takes his novel from biting parody, via horror to a beautiful yet serious depiction of the power of friendship.

Translated by Claire Dickenson

Cityscapes

23 February 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Photographer Stefan Bremer’s home town, Helsinki, provides endless inspiration, material and atmospheric. For forty years Bremer has been recording views of the maritime city, its changing seasons, its cultural events, its people. These images are from his new book – entitled, simply, Helsinki (Teos, 2012)

City kids: day-care outing in Töölönlahti park. Photo: Stefan Bremer, 2010

When I was a child, Helsinki seemed to me a grey and sad town. Stooping, quiet people walked its broad streets. The colours of the houses had been darkened by coal smoke over the years, and new buildings were coated a depressing grey.

A lot has since changed. Today, Helsinki is younger than it was in my youth. More…

Brighter than darkness

30 June 2002 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Eksyneet (‘The lost’, WSOY, 2001). Interview by Markus Määttänen

It was a white tiled wall. Too white. Sterile. He wondered how long he had been looking at it. In any case long enough to have forgotten it was a wall. It had changed into a vacuum opening up before him and then shrunk into a tunnel through whose irresistible suction he had hurtled toward the painful images of the past. The past. Yesterday. Almost yesterday. He had stared at the nocturnal entrance, clearly divided in two by the street lamps, and not just that, but now saw only a lifeless and, in its lifelessness, repellant wall. He sighed, rubbed his numb face, pushed himself off the floor and stood up.

Summer child

30 September 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Resa med lätt bagage (‘Travelling light’, 1987). Introduction by Marianne Bargum

From the very beginning it was quite clear no one at Backen liked him, a thin gloomy child of eleven; he looked hungry somehow. The boy ought to have inspired a natural protective tenderness, but he didn’t at all. To some extent, it was his way of looking at them, or rather of observing them, a suspicious, penetrating look, anything but childish. And when he had finished looking, he commented in his own precocious way, and my goodness, what that child could wring out of himself.

It would have been easier to ignore if Elis had come from a poor home, but he hadn’t. His clothes and suitcase were sheer luxury, and his father’s car had dropped him off at the ferry. It had all been arranged over the phone. The Fredriksons had taken on a summer child out of the goodness of their hearts, and naturally for some compensation. Axel and Hanna had talked about it for a long time, about how town children needed fresh air and trees and water and healthy food. They had said all the usual things, until they had all been convinced that only one thing was left in order to do the right thing and feel at ease. Despite the fact that all the June work was upon them, many of the summer visitors’ boats were still on the slips, and the overhaul of some not even completed. More…

The business of war

30 September 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Lahti (‘Slaughter’, WSOY 2004). Introduction by Jarmo Papinniemi

Major Tuppervaara put his plate down on a tree stump and walked over towards us. He had long legs and walked with a spring in his step. Twigs crunched beneath every step.

‘Okay, boys,’ he said. ‘Peckish?’

‘Yes.’

‘Take your time and listen carefully to what I’m about to tell you. The training exercise will begin soon. Your job is to help out here, you’ll be doing the medical officers’ jobs, all things you’re familiar with. During the course of this drill you will see things you have never seen before. You must not tell anyone about them. I repeat: no one. Not your father, not your mother’ not your girlfriend or your mates, not even the staff at your divisions. No one. That’s an order. Is that clear?’

‘Yes, Sir,’ said Äyräpää. Hiitola and I nodded. More…

For love or money

30 June 1994 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Paratiisitango (‘Paradise tango’, WSOY, 1993). Introduction by Markku Huotari

The bishops’ dilemma

They are waiting for Blume in the front room of the office. On the sofa sits a man whom Blume has never learned to like. He himself chose and appointed the man, for a job not insignificant from the point of view of the company. Blume has good reasons for the appointment. If he employed only men he liked, the business would have gone bankrupt years ago.

Reinhard Kindermann gets up from the sofa and waits in silence while Blume hangs up his overcoat. Mrs Giesler stands next to Blume. She does not try to help her superior take off his coat, for she knows from experience that he would not tolerate it, but the old man does allow her to stand next to him and wait in silence, like a servant expressing submission. More…

Jacob’s Dream

30 September 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Hänen olivat linnut (‘Hers were the birds’, 1967). Introduction by Pirkko Alhoniemi

‘It was Jacob’s Dream, Alma.’

How could she put it so Alma wouldn’t get hurt. Alma had ruined the surface of the painting. The pastor’s widow stood nervously in front of the window and tried to say what she’d had on her mind for several days but couldn’t quite come out with. When Alma went out of the house, the pastor’s widow would wander through the rooms and check on things. And the painting wasn’t the only object in danger, but also the birds. Their feathers were ruffled because Alma kept wiping them with a wet rag. How could she put it.

‘Alma.’

Alma turned to look at her.

‘It’s called Jacob’s Dream.’ More…

Sensitivity session

30 June 1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Ja pesäpuu itki (‘And the nesting-tree wept’). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Taito Suutarinen knew quite a bit about Freud. Where Mannerheim’s statue now stands, Taito felt that there ought instead to be an equestrian statue of Sigmund Freud. It would be like truth revealed.

Freud, urging on his trusty stallion Libido, would be clad from head to foot in sexual symbols – hat, trousers, shoes: one hand thrust deep into his pocket, the other grasping a walking-stick. The stick would point eloquently in the direction of the railway tracks, where the red trains slid into the arching womb of the station.

Taito had also attended a couple of seven-day sensitivity training courses, where people expressed their feelings openly, directly and spontaneously. By the end of the first course Taito was so direct and spontaneous that he couldn’t get on with anybody. By the end of the second he was so open that everyone was embarrassed. Every member of the group had cried at least once, except the group leader. Never before had Taito witnessed such power. He could not wait to found a group of his own. Taito’s group met in a basement room, where they reclined on mattresses to assist the liberation process. Everyone was free to have problems, quite openly. You were not regarded as ill: on the contrary, if you realized your problem you were more healthy than a person who still thought he mattered. Moreover, as Taito, fixing you with his piercing gaze, was always careful to emphasize, every problem was ultimately a sexual problem. Taito would spontaneously scratch his crotch as he spoke, making it clear that he himself had virtually no problems left. More…

All aboard

30 December 2005 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Nooakan parkki (‘Noahannah’s barque’, Tammi, 2005)

A Royal Navy Three-funnel Brig

The crew:

Matilda, an overeating cat

Five geese

20 hens

A fat narcoleptic cock

A couple of ducks

A goat

Three dogs

48 bats

Six woodpeckers

104 titmice

There’s a north-westerly blowing.

Djibouti 253

Three feet long from the east and five from the west, plus two hat-heights above the earth’s surface; standing on the sauna bench I scan the horizon for any omens – a raven, a woodpecker or a flock of waxwings. A crow would do. More…

Time difference

30 December 2003 | Fiction, Prose

A short story from Kalliisti ostetut päivät (Dearly bought days, Otava, 2003)

She arrived at the airport too early, as always. The reason was not that connections from the small town in which she lived were slow and difficult, or even that she liked the airport’s atmosphere of swift departures and long waits. No; she wanted to spend time at the airport to see that the planes took off and landed without anything awful happening. She wanted to see that a departing plane’s acceleration was rapid, that the plane left the asphalt of the runway elegantly, that its tail did not hit the ground as it rose, break, the plane explode, catch fire, but that, like an arrow fired into the air, following its flight path, it curved upward and, sunlight glancing off the metal of the body, disappeared from view. She wanted to see that the landing gear of a descending plane was out, as it should be, that a tyre did not burst as it hit the ground, at that there was no ice or oil on the runway; that the brakes worked, and that the fire engines at the edge of the airfield stayed in place as a sign that all was well. More…