Authors

Master of Satire

Issue 1/1981 | Archives online, Authors

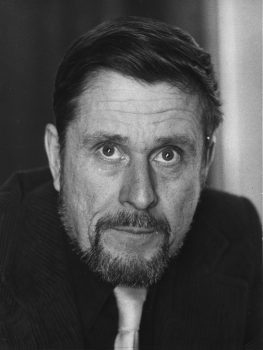

Henrik Tikkanen. Photo: Schildts & Söderströms

Henrik Tikkanen (born 1924) comes of a cultured Swedish-speaking family: his father was an architect, his grandfather an eminent art historian. But it is not only linguistically that Tikkanen belongs to a minority: in a land famous for epic he expresses himself in epigram and satire; in a land of lakes and forests he is an unashamed city-lover; in a land addicted to military virtues he stands out as a pacifist; in a land of books he writes for the newspapers. And in one of his autobiographical novels he confesses that he lacks the sentimental streak that motivates everything that is ever done in Finland.

For a Finnish author, Tikkanen has an exceptionally close relationship with the daily press. He earned his living as a working journalist, initially with Hufvudstadsbladet, the leading Finnish newspaper in Swedish, and later with Helsingin Sanomat, the biggest of the Finnish papers. After serving in the war it became his ambition to be Finland’s ‘best and only’ newspaper artist: he certainly achieved it. As a columnist and documentary feature writer who is at the same time a brilliant wit and coiner of epigrams, and who illustrates his own text, he still has no equal; indeed it would be hard to think of anyone who could even rank as a competitor. More…

On Daniel Katz

Issue 4/1980 | Archives online, Authors

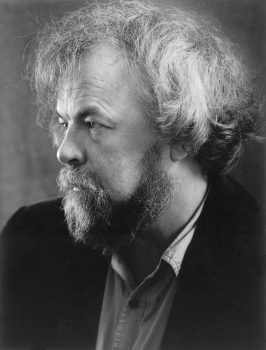

Daniel Katz. Photo: Veikko Somerpuro/WSOY.

Daniel Katz (born 1938) is a member of Finland’s small Jewish community and the first Finnish writer to emerge from that background. The publication of his first book coincided roughly with the appearance in America of a wealth of Jewish literature. Katz has much in common with American Jewish writers, particularly in his parodies of conventional religious practices, but the Jewish community he writes about relates to the general social environment in a very different way. Writers like Philip Roth are concerned with a social group that is tightly hemmed in by its own claustrophobic boundaries, whereas Katz’s Jews, living alongside the reserved and at times withdrawn Finns, stand out as exceptionally extroverted and sociable beings; their Jewishness is not a fetter but their innate key to freedom. More…

Juhani Niemi on Väinö Linna

Issue 4/1980 | Archives online, Authors

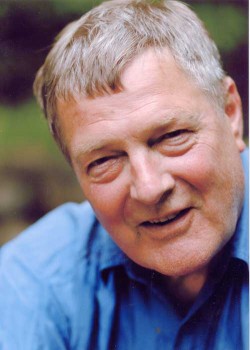

Väinö Linna. Photo: WSOY

Väinö Linna fits squarely into one of the dominant patterns of twentieth century literary development in Scandinavia. Like many writers of the period, Linna came from a working class background and struggled to free himself from that environment through self-education. He had no special interest in politics but his natural leanings were moderately left-wing. He isn’t a ‘political’ writer as such, and it would be simplistic to apply labels to his views. His central interests, which directly affect his style, are a concentration on firstly, acute social observation and, secondly, social analysis. Through novels in this genre – and Linna is without doubt a master – the reader finds a world and all its influences, from the personal to the historical and economic dissected, the casings laid back, the true juxtapositions revealed.

The process can be powerful and effective and Linna’s major works Tuntematon Sotilas (‘The Unknown Soldier’, 1954, English translation 1957) and the trilogy Täällä Pohjantähden alla (‘Here beneath the North Star’, 1960-62) have struck deep into the Finnish national consciousness radically influencing the way events in recent Finnish history have been viewed by a wide audience of readers. Both works have been enormously popular: the characters have so accurately caught the Finnish personality that they have become part of the nation’s mythology. More…

Interview with Kerttu-Kaarina Suosalmi

Issue 2/1980 | Archives online, Authors, Interviews

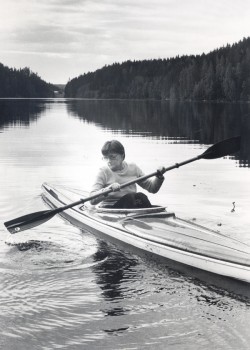

In these days of seminars, conferences, discussions and panels, Kerttu-Kaarina Suosalmi is in constant demand as a fluent and lively speaker on a variety of subjects. Whether the occasion is a gathering of young theologians, a pacifist rally on Independence Day, or a seminar for young Marxists, what she has to say is always both shrewd and stimulating. Her manner of speaking suggests not so much a radio announcer as a force of nature. Not that Kerttu-Kaarina Suosalmi is ‘a writer with a message’ in the accepted sense. She does not indulge in polemics; her novels are neither documentary nor autobiographical, but pure works of the imagination. Critics speak of her recent books as artistic triumphs. Nevertheless, the relevance of her work to present-day conditions and problems is strongly felt by the reading public. It is rare for such an abundance and variety of material to be combined with such qualities as spontaneity of form and excellence of expression. Suosalmi’s first book appeared as long ago as 1948, a collection of poems entitled Melanmitta (‘A stroke of the paddle’). Her early works in prose, Synti (‘The sin’, 1957), a collection of short stories, and the novel Neitsyt (‘The virgin’, 1964) were tightly constructed, ‘well-made’ works in the accepted Finnish tradition. A more personal style of writing made its appearance with Hyvin toimeentulevat ihmiset (‘These affluent people’, 1969). In this novel, constructionally speaking, Suosalmi breaks new ground: there is no consecutive plot, the book being built up of sections written from the points of view of the various ‘affluent people’ of the title, the thematic unity becoming evident only in the context of the entire novel. More…

Money, Morals and Love

Issue 1/1980 | Archives online, Authors

Maria Jotuni. Photo: Atelier Nyblin / CC-BY-4.0

Maria Jotuni‘s reputation as a writer rests on her daring and highly individual portrayals of women and on her gifts as a dramatist. Her works concentrate on analyses of the human condition, the contradictions, the frustrations, the fantasies. As the creative ‘observer’ she is both deeply sympathetic and ruthlessly revealing.

Maria Jotuni, whose centenary is celebrated this year, grew up in the eastern Finnish province of Savo and her early work draws richly on that background for subject matter and local colour. Her style, which over the years was honed and polished into a unique form of expression, certainly owes something to the lilting rhythms of the Savo dialect – and something to the lyricism of the Finnish Bible, with which she was familiar from her earliest years. Maria Haggrén, as she was born, was the second of six children; they lived in Kuopio, the home town of J. V. Snellman (1806–81), a man who did much to formulate the Finnish national identity, and of Minna Canth (1844–97), one of Finland’s major woman writers. The Haggréns were not wealthy, but they believed strongly in the pursuit of learning and knowledge. The home also provided a fruitful contact with rural life with opportunities to listen to the chatter and tales of the farm boys and servant girls. More…

On Caj Westerberg

Issue 1/1980 | Archives online, Authors

Caj Westerberg. Photo: Pentti Sammallahti

Caj Westerberg established his reputation with the publication, in 1967, of his first volume of poems: Onnellisesti valittaen (‘Cheerful complaint’). The work was immediately praised for its descriptive power and visual imagery. The other outstanding feature – preserved in subsequent works – is the author’s capacity for emotion, for a passionate involvement in human existence, casting the sensitive individual from the crest of ecstasy to the trough of despair. In Westerberg’s next two collections, Runous (‘Poetry’, 1968) and En minä ole ainoa kerta (‘I am not the only one’, 1969), these key features are firmly sustained. At the same time, Westerberg is beginning to extend the mordancy of his themes. In his fourth book, Uponnut Venetsia (‘Sunken Venice’, 1972), the style has became move conversational and laconic, but does not deviate from his main thematic concerns. Westerberg’s work can be seen as a cool, developing continuum: all the poems, whether long or short, whether aphoristic epitomes of experience or pure ‘imagistic’ visions, convey a unified individual response to the world and existence, and a prevailing intensity. With each publication, brought out as all his earlier works by Otava, Westerberg has developed and enhanced his style. His two most recent works, Kallista on ja halvalla menee (‘It comes dear and it’s going cheap’, 1975) and Reviirilaulu ‘Territorial song’, 1978), have all the marks of works which will become classics. Westerberg’s poems are moving and full of surprising associations; he is both sensitive to the present and alive to the past. His style maintains a fine balance between the conversational and the stylized. Westerberg takes the role of the poet seriously. At a recent conference he put it thus: ‘The poet’s fundamental impulse is to reveal the hidden. That is one of his tasks. That is his folly. The poet is the seer, the prophet, the truth-teller.’

Translated by Mary Lomas

The Poet as a Progressive

Issue 3/1979 | Archives online, Authors

Claes Andersson. Photo: Johan Bargum.

Why do some poets adopt a chill tone or an intellectual stance, while others bleed in public, clench their fists or bellow with pain? Temperament alone cannot explain this. Poetical traditions, and the current climate, are more influential.

Modern Swedish poetry – in fact all Scandinavian poetry, including that of Finland – has inclined toward German and Continental Expressionism. This is, in essence, a romantic tradition, and there are other, more endogenous romantic traditions, as well, driving poets the same way. In such an ambience any pronouncedly intellectual poet will always seem exceptional. He will risk being accused of aloofness or disdain, be easily damned as a ‘difficult’ writer. Rabbe Enckell and Paavo Haavikko in Finland, Gunnar Ekelöf in Sweden, are cases in point.

Claes Andersson (born 1937) seems to belong to this category. He certainly tells his readers where he stands, unapologetically. But he is also a lover of his language – the Swedish spoken in Finland – and he likes to play intellectual games with the language, to coin a word or a phrase and turn it over, sometimes upside-down, to reflect and comment on the language itself: ‘Words,’ he once wrote, ‘possess hidden valences – shown, for instance, when the word Sodium jumps into the word Water to cool itself, never suspecting what will happen. Hidden tensions may thus be disclosed.’ More…

On Markku Lahtela

Issue 3/1979 | Archives online, Authors

Markku Lahtela is one of the more colourful personages on the Finnish literary scene. He studied at the universities of Moscow and Munich, served on the editorial staff of an encyclopedia, published his first book in 1964, and proclaimed that his favourite writer was Anatole France. The powerful radical currents of the 1960s took him out into the streets as a demonstrator: he wrote scripts for a theatre group that went in for staging ‘happenings’, took part in politics as the enfant terrible of the Centre Party, publicly burnt his military passbook, translated Herbert Marcuse, and became an enthusiast for the anti-authoritarian educational experiments of A. S. Neill and his followers. Out of these restless years came two long, highly personal and very uneven novels, Se (‘It’, 1966) and Yksinäinen mies (‘The solitary man’, 1976), in which Lahtela is primarily concerned with a young man’s difficult family relationships, and seeks to demonstrate his fundamental honesty by recourse to automatic writing. Early in the 1970s he published three short collections of philosophical observations and stories. These, the fruit of wide but indiscriminate reading, amounted to little more than the compilations of an amateur, the basic idea being to demonstrate, by means of biological and psycho-analytical arguments, the primacy of the mother-child relationship among the factors affecting a human being’s development. More…

On Lassi Nummi

Issue 1/1979 | Archives online, Authors

Lassi Nummi, 1957. Photo: Kuvasiskot / CC-BY-4.0

Lassi Nummi has never been afraid to say that a poem has a right to be poetry. Throughout his thirty-year career in letters he has consistently backed the special task of poetry, its right to independent life. And the other side of this is the unconstrained poem’s tutelage of whatever it is in man that is striving upwards out of the half-light into consciousness.

Nummi lets his poems ring. He is not afraid even of the pastoral, and he risks the ancient methods of the lyric. He thinks a flower garden is acceptable as a garden of flowers, and it is not proper to disparage it as a failed cornfield. With equal consistency Nummi has promoted literature as a social institution – as one of its most prominent representatives himself: a critic and chronicler with a compound eye on events in the visual arts, literature and music. Music is a special component of his own poetry, of course. More…

On Erno Paasilinna

Issue 4/1978 | Archives online, Authors

Erno Paasilinna. Photo: Irmeli Jung

In one of his essays Erno Paasilinna speaks of a modern phenomenon, the ‘quasi-author’. A quasi-author is the kind of literary buff who writes for the papers, takes part in congresses, sits in panels and appears frequently on television. Wherever there is controversy, be it over the function of the President, the legality of strikes, the abortion laws, the evangelical movement or the present state of lyric poetry, the quasi-author is invariably to be found. Paasilinna atones for his irony by freely admitting that he is himself a typical specimen of the breed.

For the concept of the quasi-author Paasilinna refers us back to Ilya Ehrenburg, who noted in his memoirs that the profession of authorship had been undergoing a steady diminution of social and political influence ever since the early 30s. Since Ehrenburg’s day the process has accelerated: television, efficient communications, and the ceaseless output of ‘information’ by what amounts to a major modern industry, have finally toppled the novelist from the throne he successfully occupied for so long. The quasi-author has replaced him, availing himself of all the new media in the hope of achieving a more rapid and direct impact on the public – and perhaps also of preserving the traditional influence of the writing fraternity. Erno Paasilinna was born in 1935 near Petsamo (now Pechenga) on the Arctic coast: from 1922 till 1944 this region was part of Finland. Evacuated during the upheavals of the Second World War, the family was forced to lead the nomadic life of refugees, wandering across the Arctic wastes as far as Norway before they were able to find a settled home in Finland. Erno Paasilinna has not rejected the landscape or the traditions of his native area: he has edited four anthologies of extracts from early accounts of travel in Lapland. It was in Northern Finland, too, that Paasilinna completed his education (he attended the Lapland College of Further Education) and began his writing career. More…

On Eeva-Liisa Manner

Issue 4/1978 | Archives online, Authors

Eeva-Liisa Manner. Photo: Tammi.

It is difficult to discuss Eeva-Liisa Manner’s poetry in isolation from her other writing. In both prose and drama she is a significant figure in Finnish literature, and, for instance, one of her plays – Poltettu oranssi (‘The burnt-out orange’) – had a nine-year run at the Tampere Workers’ Theatre.

Seen from one angle, a Manner poem is an opportunity to speak, to have a say on the day’s occurrences, such as the occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968. Yet a poem of hers is always distanced. Perhaps it is mediated through the eternal myth of the East and West; or perhaps the events are seen from some altered perspective – from ‘a distant present’. Our own time may be seen, for example, from the point of view of the Cambrian Age. Myths and the animals associated with myth are consciously brought forward by the ‘I’ of the poems, always with a delicate irony. The horse is the most prominent and beloved of these beasts (the Creator ‘succeeded best’ with him), and he is identified with Jung’s animus. Discursive philosophy is not prominent in Finland. Finnish philosophers tend to be philosophers of science and technology – the purveyors of wisdom are the poets, and they are by no means bad at it. Taking a risk with the reader’s indulgence I could define Eeva-Liisa Manner as a philosophical poet meaning that her lyricism is charged with implication. The fine control of semantic content, as always in lyrical poetry, is achieved through her imagery and music; but her thematic centres, the problems she confronts, are seriously or ironically philosophical. In some of her poems, such as ‘A Logical Tale’. she may actually build up the lyric within an apparently tight case of thought; this is, of course, both a dig at philosophy and a philosophical point. Sometimes the digs are very hard. The nuances are many. More…

On Alpo Ruuth

Issue 3/1978 | Archives online, Authors

Alpo Ruuth. Photo: Sakari Majantie / Tammi

Alpo Ruuth (born 1943) grew up in Sörnäinen, a working-class quarter of Helsinki, amid dirty grey tenements, railway goods yards, machine shops, timber yards and slaughterhouses; a district reeking of rust and dust, of gasometers, steam locomotives, pinewood, toad-in-the-hole and roasting coffee. Ruuth completed three years of secondary schooling and then decided that he had had enough. He worked as a garage hand, a shoemaker, a casual labourer, a salesman and a storekeeper. The publication of his first novel, Naimisiin (‘Getting married’, Tammi, 1967) set him free to adopt writing as a career.

Ruuth first became known to a wider public through his novel Kämppä (‘The commune’, Tammi, 1969 ). This describes the adolescent years of a group of Sörnäinen boys who live like a tribe of savages in this urban jungle. They establish a commune of their own, cut off completely from the adult world, and rely on a process of trial and error to teach them how to live. The charm of the book comes from the spontaneity and quick reactions of these teen-age youngsters: chattering, mimicking, footballing or fornicating, they are all the time as alert as puppies, while the life of the city around them goes on ‘for real’. The final section of Kämppä describes how they eventually slot themselves into the community. Most of them accept their fetters with resignation, but there is one – the chief character of the novel – who strives to maintain his critical attitude to the values which dominate his surroundings, and to live up to it in practice. Some of Ruuth’s finest writing in this novel is devoted to the harmonious family background of this young man’s early years. He seems to be saying that ethically valid solutions to life’s problems grow out of the personal relationships of early childhood. More…

On Matti Pulkkinen

Issue 2/1978 | Archives online, Authors

Matti Pulkkinen. Photo: Gummerus

Matti Pulkkinen’s grandfather was born in 1842 in a forest village close to the Russian border, in an area which could only be reached by water. When he grew up he became a tar-burner, a traditional occupation in north-east Finland. Pulkkinen’s father worked for the Otava Publishing Company in the early years of the present century, a time when ordinary Finns were beginning to show a real interest in literature. In his home in one of the most remote parts of North Karelia, he assembled a library which ranged from Mark Twain to the detective stories of G. K. Chesterton. He was 70 when his youngest son, Matti, was born in 1944. Dostoyevsky and Nietzsche were the two writers whose works did most to stimulate Matti Pulkkinen’s enthusiasm for literature. After leaving school he set out to see the world. He worked as a lumberjack, a primary school teacher, a statistics clerk in a gynaecological hospital, a bank teller, an accounts clerk, and later as a carpenter, took part in the restoration of the medieval church at Vanaja. From 1969 to 1971 Pulkkinen worked as a nurse in mental hospitals in Frankfurt, West Berlin and Bern. While in Switzerland he became interested in Jungian psychology and modern group therapy.

Pulkkinen’s novel, Ja pesäpuu itki (‘And the nesting-tree wept’, Gummerus), published in 1977, was awarded the J.H. Erkko Prize for the best first novel of the year and the Kalevi Jäntti Memorial Prize. It rapidly became a best seller and has already had two reprints. More…

On Mirkka Rekola

Issue 2/1978 | Archives online, Authors

Mirkka Rekola. Photo: Elina Laukkarinen/WSOY

The very title of Mirkka Rekola‘s latest collection of poems, Kohtaamispaikka vuosi (‘Meetingplace the year’, Werner Söderström, 1977), reveals a theme central to Rekola’s poetry: that of unity. The time is the place. ‘I do not imagine I shall meet you this year. / This place will be here in summer.’ Rekola has a particular way of using language of the most intense concentration, so that it brings out unity between a wide variety of moods. ‘I shall meet you this year’ also means that you are this year. ‘This place will be here in the summer’ means that it is autumn and this place (a summer café) will remain deserted until the summer, but also that this place will remain there as the summer.

‘The world, a table already laid, there you see your hunger.’ ‘At the same time a little thirsty and a cowberry.‘ The correspondence of place, the synchrony of season and the general sense of undividedness produce countless pictorial and therefore concrete expressions throughout Rekola’s poetry. ‘I spread my hands / and someone yawned, / I held my fingertips in the breeze / and the boats slid into the water.’ ‘The child said to the old man: you are bent, while I am so little.’ ‘A shout is heard which is no other’s.’ Rekola’s concrete and graphical mode of expression is also based on the same philosophy: ‘Do not make a picture, everything is [a picture]’. ‘The sun, star of the night, introduces the day. And the world is so talkative in its dreams.’ More…

On Matti Rossi

Issue 1/1978 | Archives online, Authors

Matti Rossi. Photo: SKS archives

The appearance in 1965 of Matti Rossi’s (born 1934) first work in Finnish, Näytelmän henkilöt (‘Dramatis personae’, Tammi), brought him immediate recognition as an important writer. It confirmed him as a skillful translator – he had already ten important translations to his name – and revealed a new but already mature poet. Näytelmän henkilöt contains biting political parody, highly original myth verse and the Finnish version of a series of poems on Vietnamese themes, which he had first published in English.

Rossi has always worked in many styles and genres. Leikkeja kahdelle (‘Games for two’, Tammi, 1966) is a magnificent collection of sensual love poems; his fantasy poem for the stage, Tilaisuus (‘The occasion’, Tammi, 1967), examines the nature and causes of violence; the events in Czechoslovakia are the subject of his analytical political satire Käännekohta (‘Turning-point’), written as a play for television in 1969. These were followed by a long period in which Rossi’s poetry reflects his political commitment to the far left. He brought out a book about his experiences during a visit of more than a year to South America, and his scathing poetry has always played its part in political controversy. He has composed songs for the stage, and an outstanding ballad narrative, Puulintujen vuolija (The carver of wooden birds’, 1975). More…

-

Currently browsing

Interviews with Finnish authors and introductions to their work

-

RSS feed

Subscribe to RSS feed for Authors

-

List of authors and contributors

- Abu-Hanna, Umayya

- Ågren, Gösta

- Aho, Hannu

- Aho, Juhani

- Aho, Claire & Westö, Kjell

- Ahola, Suvi

- Ahti, Risto

- Ahtola-Moorhouse, Leena

- Ahvenjärvi, Juhani

- Ala-Harja, Riikka

- Alftan, Maija

- Alhoniemi, Pirkko

- Anderson, John

- Andersson, Claes

- Andersson, Jan-Erik

- Andtbacka, Ralf

- Anhava, Tuomas

- Antas, Maria

- Apunen, Matti

- Aro, Tuuve

- Aronpuro, Kari

- Autio, Milla

- Bargum, Johan

- Bargum, Marianne

- Barrett, David

- Binham, Philip

- Björling, Gunnar

- Blau DuPlessis, Rachel

- Bolgár, Mirja

- Boucht, Birgitta

- Bremer, Caj

- Bremer, Stefan

- Brotherus, Elina & Ala-Harja, Riikka

- Byggmästar, Eva-Stina

- Canth, Minna

- Carlson, Kristina

- Carpelan, Bo

- Chan, Stephen

- Chorell, Walentin

- Diktonius, Elmer

- Ekman, Michel

- Ekroos, Anna-Leena

- Enckell, Agneta

- Enckell, Martin

- Enqvist, Kari

- Envall, Markku

- Eskola, Kanerva

- Fagerholm, Monika

- Flint, Austin

- Forsblom, Harry

- Forsblom, Sabine

- Forsström, Tua

- Gothóni, Maris

- Granö, Veli

- Gripenberg, Catharina

- Gröndahl, Satu

- Grünthal, Satu

- Haanpää, Pentti

- Haapala, Vesa

- Haasjoki, Pauliina

- Haatanen, Kalle

- Haavikko, Paavo

- Hämäläinen, Helvi

- Hämäläinen, Timo

- Hännikäinen, Timo

- Hänninen, Anne

- Hannula, Risto

- Harju, Timo

- Härkönen, Leena

- Harmaja, Saima

- Hassinen, Pirjo

- Havukainen, Aino & Toivonen, Sami

- Hawkins, Hildi

- Heikkilä-Halttunen, Päivi

- Heikkonen, Olli

- Heinimäki, Jaakko

- Hejkalová, Markéta

- Hellaakoski, Aaro

- Hertzberg, Fredrik

- Hiidenheimo, Silja

- Hiltunen, Eija Irene

- Hökkä, Tuula

- Holappa, Pentti

- Hollo, Anselm

- Holmström, Johanna

- Honkala, Juha

- Hotakainen, Kari

- Huldén, Lars

- Huotari, Markku

- Huotarinen, Vilja-Tuulia

- Huovi, Hannele

- Huovinen, Veikko

- Hurme, Juha

- Hyry, Antti

- Idström, Annika

- Ingström, Pia

- Inkala, Jouni

- Isomäki, Risto

- Istanmäki, Sisko

- Itkonen, Jukka

- Jalonen, Olli

- Jama, Olavi

- Jansson, Tove

- Järnefelt, Arvid

- Järvelä, Jari

- Järvinen, Outi

- Jeremiah, Emily

- Joenpelto, Eeva

- Joenpolvi, Martti

- Joensuu, Matti Yrjänä

- Jokela, Markus

- Jokinen, Heikki

- Jokisalo, Ulla & Kortelainen, Anna

- Jones, W. Glyn

- Jotuni, Maria

- Juntunen, Tuomas

- Juvonen, Helvi

- Kähkönen, Sirpa

- Kaila, Tiina

- Kaipainen, Anu

- Kanto, Anneli

- Kantokorpi, Mervi

- Kantokorpi, Otso

- Kantola, Janna

- Karlström, Sanna

- Karonen, Vesa

- Katajavuori, Riina

- Katz, Daniel

- Kihlman, Christer

- Kiiskinen, Jyrki

- Kilpi, Eeva

- Kilpi, Volter

- Kinnunen, Aarne

- Kirstinä, Leena

- Kirstinä, Väinö

- Kirves, Jenni

- Kivi, Aleksis

- Knapas, Rainer

- Kokko, Karri

- Kokko, Hanna & Bargum, Katja

- Kontio, Tomi

- Korhonen, Riku

- Korsström, Tuva

- Koskela, Lasse

- Koskelainen, Jukka

- Koskimies, Satu

- Koskinen, Sinikka

- Krohn, Leena

- Kulmala, Teppo

- Kunnas, Kirsi

- Kupiainen, Teemu & Bremer, Stefan

- Kurkijärvi, Gene

- Kuusisto, Stephen

- Kylätasku, Jussi

- Kyrö, Tuomas

- Kytöhonka, Arto

- Laaksonen, Heli

- Lahtela, Markku

- Lahti, Leena

- Laine, Jarkko

- Laitinen, Kai

- Lander, Leena

- Lassila, Pertti

- Laurén, Anna-Lena

- Leche, Johan & Grysselius, Johan

- Lehtola, Erkka

- Lehtola, Jyrki

- Lehtonen, Joel

- Lehtonen, Soila

- Leka, Kaisa

- Lesser, Rika

- Liehu, Rakel

- Liksom, Rosa

- Lilius, Carl-Gustav

- Lindberg, Petter

- Lindblad, Kjell

- Lindgren, Minna

- Lindgren, Minna & Löytty, Olli

- Lindén, Zinaida

- Linna, Väinö

- Lintunen, Maritta

- Liukkonen, Leena

- Liukkonen, Tero

- Lomas, Herbert

- London, Mindele

- Lounela, Pekka

- Löytty, Olli

- Lundberg, Ulla-Lena

- Luntiala, Hannu

- Lydecken, Arvid

- Määttänen, Markus

- Mäkelä, Hannu

- Mäkinen, Raine

- Malkamäki, Sari

- Manner, Eeva-Liisa

- Mannerkorpi, Juha

- Manninen, Teemu

- Marttila, Hannu

- Marttila, Mervi

- Mauriala, Vesa

- Mazzarella, Merete

- McDuff, David

- Mehto, Katri

- Melleri, Arto

- Meri, Veijo

- Meriluoto, Aila

- Metsähonkala, Mikko

- Mickwitz, Peter

- Mikkola, Marja-Leena

- Mikkonen, Sari

- Mörö, Mari

- Musturi, Tommi

- Neovius Deschner, Margareta

- Nevala, Maria-Liisa

- Nevanlinna, Arne

- Nevanlinna, Tuomas

- Niemi, Irmeli

- Niemi, Juhani

- Nieminen, Kai

- Nieminen, Pertti

- Nissilä, Anna-Leena

- Nordell, Harri

- Nordgren, Ralf

- Nummi, Jyrki

- Nummi, Lassi

- Nummi, Markus

- Oja, Vesa

- Oksanen, Aulikki

- Oksanen, Kimmo

- Olsson, Hagar

- Onerva, L

- Onkeli, Kreetta

- Orlov, Janina

- Otonkoski, Lauri

- Paasilinna, Arto

- Paasilinna, Erno

- Pääskynen, Markku

- Paasonen, Markku

- Paasonen, Ranya

- Päätalo, Kalle

- Paavolainen, Nina

- Pakkala, Teuvo

- Paksuniemi, Petteri

- Palmgren, Reidar

- Papinniemi, Jarmo

- Parland, Henry

- Parras, Tytti

- Parvela, Timo

- Pekkanen, Toivo

- Peltonen, Juhani

- Pennanen, Eila

- Petäjä, Jukka

- Petterson, Viktor

- Pettersson, Joel

- Peura, Annukka

- Peura, Maria

- Pimenoff, Veronica

- Pirilä, Marja

- Pohjola-Skarp, Riitta

- Polkunen, Mirjam

- Pulkkinen, Matti

- Pyysalo, Joni

- Raevaara, Tiina

- Raittila, Hannu

- Rajala, Panu

- Rane, Irja

- Rapo, Jukka & Rotko, Lauri, Jukka

- Rasa, Risto

- Rekola, Mirkka

- Riikonen, H.K.

- Rimminen, Mikko & Salokorpi, Kyösti

- Ringbom, Henrika

- Ringell, Susanne

- Rintala, Paavo

- Roine, Raul

- Roinila, Tarja

- Rönkä, Matti

- Rönnholm, Bror

- Rossi, Matti

- Runeberg, Fredrika

- Runeberg, Johan Ludvig

- Ruohonen, Laura

- Ruuth, Alpo

- Saarikangas, Kirsi

- Saarikoski, Pentti

- Saarikoski, Saska

- Saaritsa, Pentti

- Sahlberg, Asko

- Saint-Germain, Claire

- Saisio, Pirkko

- Salama, Hannu

- Sallamaa, Kari

- Salmela, Aki

- Salmela, Alexandra

- Salmenniemi, Harry

- Salminen, Arto

- Salminiitty, Satu

- Salo, Merja

- Sammallahti, Pentti & Thrane, Finn

- Sandelin, Peter

- Sandman Lilius, Irmelin

- Säntti, Maria

- Sariola, Esa

- Sarkia, Kaarlo

- Saurama, Matti

- Savolainen, Mikko

- Saxell, Jani

- Schatz, Roman & Jarla, Pertti

- Schildt, Runar

- Schoolfield, George C.

- Seppälä, Arto

- Seppälä, Juha

- Siekkinen, Raija

- Sihvo, Hannes

- Sihvonen, Lauri

- Sillanpää, Frans Emil

- Sillanpää, Johanna

- Simonsuuri, Kirsti

- Sinervo, Helena

- Sinisalo, Johanna

- Sirola, Jouko

- Sironen, Esa

- Skiftesvik, Joni

- Snellman, Anja

- Snickars, Ann-Christine

- Södergran, Edith

- Söderling, Trygve

- Statovci, Pajtim

- Stenberg, Eira

- Strandén, Tiia

- Sund, Lars

- Suosalmi, Kerttu-Kaarina

- Susi, Heimo

- Susiluoto, Saila

- Svedberg, Ingmar

- Tähtinen, Tero

- Tahvanainen, Sanna

- Takala, Riikka

- Tamminen, Petri

- Tapio, Juha K.

- Tapola, Katri

- Tapola, Katri & Talvitie, Virpi

- Tarkka, Pekka

- Taskinen, Satu

- Tate, Joan

- Tavi, Henriikka

- Tervo, Jari

- The Editors

- Thölix, Birger

- Tietäväinen, Ville

- Tiihonen, Ilpo

- Tikka, Eeva

- Tikkanen, Henrik

- Tikkanen, Märta

- Tirkkonen, Sinikka

- Toivio, Miia

- Topelius, Zachris

- Tossavainen, Jouni

- Tuomi, Panu

- Tuominen, Maila-Katriina

- Tuominen, Mirjam

- Turkka, Jouko

- Turkka, Sirkka

- Turtiainen, Arvo

- Turunen, Heikki

- Tuuri, Antti

- Tynni, Aale

- Tyyri, Jouko

- Urbom, Ruth

- Uschanov, Tommi

- Utrio, Kaari

- Vainio, Väinö

- Vainonen, Jyrki

- Väisänen, Hannu

- Vakkuri, Juha

- Vala, Katri

- Valkeapää, Nils-Aslak

- Valkonen, Kaija

- Valoaalto, Kaarina

- Valtaoja, Esko

- Vartio, Marja-Liisa

- Venho, Johanna

- Verronen, Maarit

- Viikari, Auli

- Viita, Lauri

- Virkkunen, Juha

- Virolainen, Merja

- Virtanen, Arto

- Vuoristo, Sari

- Wahlström, Erik

- Waltari, Mika

- Warburton, Thomas

- Westerberg, Caj

- Westö, Kjell

- Westö, Mårten

- Widén, Gustaf

- Willamo, Heikki

- Willner, Sven

- Witesman, Owen

- Zilliacus, Clas

- von Koskull, Agneta

- von Schoultz, Solveig

-

Yearly archive

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.