Search results for "🚒💋 Generic viagra caps, sildenafil citrate, 100mg > ☑ www.WorldPills.NET 🧯☑ <. discount online pharmacy📪✅⧒:sildenafil - Amazon.com, sildenafil price,sildenafil 100mg tablets for sale,sildenafil citrate tablets 100mg"

Tchotchkes for the tsar

11 August 2011 | Reviews

Cornflower and ear of oats: one of the several Fabergé gemstone ornaments now owned by Queen Elizabeth of England (gold, rock crystal, diamonds, enamel, ca 18 cm)

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm

Fabergén suomalaiset mestarit

[Fabergé’s Finnish masters]

Design: Jukka Aalto/Armadillo Graphics

Helsinki: Tammi, 2011. 271 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-31-5878-1

€57, hardback

In its online shop, the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg sells a copy of a most delicate, enchanting little nephrite-and-opal lily of the valley that perfectly imitates nature, sitting in a vase made of rock crystal that looks like a glass of water.

These small flowers made of gold and gemstones were manufactured by the jeweller Fabergé a hundred years ago. The lily of the valley was the most frequently used floral motif in the Fabergé workshops – it was the favourite flower of Empress Alexandra (1872–1918), and the imperial family was the the foremost client of the world’s foremost jeweller.

The replica (13.5 centimetres high) is available at the Hermitage as a ‘luxury gift’ for the price of mere $3,300. (N.B. Since we published this review, the ‘luxury gift’ items seem to have disappeared from the Hermitage online shop selection, so we have removed the link. Several Fabergé egg replicas are available though, ranging in price from $200 upwards – link below.)

For those who feel the price is excessive, there is also a rather modestly-priced little bay tree (original: gold, Siberian nephrite, diamonds, amethysts, pearls, citrines, agates and rubies as well as natural feathers, about 30 centimetres tall, featuring a little bird that emerges flapping its wings and singing when a small key is turned) at just $ 219,95. Despite its form, it is classified as one of the famous imperial Easter eggs. (However, as I write, this item is unfortunately sold out…) More…

Digital dreams

4 February 2009 | Essays, Non-fiction

In this specially commissioned article, the first for the new Books from Finland website, Leena Krohn contemplates the internet and the invisible limits of literature.

Leena Krohn on the way to Cape Tainaron, Southern Peloponnese, Greece; this is where Europe ends. Her novel entitled Tainaron appeared in 1985. – Photo: Mikael Böök (2008)

The world wide web, whose services most of us now use for work or entertainment, is a greater invention than we have, perhaps, realised up till now: according to the writer Leena Krohn, it is nothing less than an evolutionary leap

Technology combats the limitations of our senses, geography, and time. The human eye can’t compete with the visual acuity of an eagle, or even a cat, but with the best telescopes it can see into the early history of the universe, with new electron microscopes it can distinguish individual atoms.

The human senses nevertheless have an unbelievably broad bandwidth. About a million times more data flows to our brains by means of our senses than we could ever grasp consciously. More…

Happy birthday to us!

13 February 2014 | Letter from the Editors

Picture: Wikipedia

It’s been five years since Books from Finland went online, and we’re celebrating with a little bit of good news.

In the past year, the number of visits to the Books from Finland website has grown by 11 per cent. The number of US and UK readers grew by 29 per cent, while the number of readers in Germany – stimulated perhaps by the publicity Finnish literature is attracting as a result of its Guest Country status at this year’s Frankfurt Book Fair – increased by an astonishing 59 per cent.

We’re chuffed, to put it mildly – and very thankful to you, dear readers, old and new. More…

Art online

23 May 2013 | In the news

Helene Schjerfbeck’s The convalescent (1888) on the cover of the guidebook of the Ateneum Art Museum

Attention lovers of Finnish art: the Ateneum Art Museum in Helsinki has joined the international Google Art Project (begun in 2011), with 260 participating art institutes and more than 40,000 works of art as high-resolution images.

The website also includes information on the paintings. Among the 55 images from Ateneum on show now are many of the great works of the golden period of Finnish art (1880–1910), including Hugo Simberg’s darkly cute The Garden of Death, Albert Edelfelt’s heartbreakingly beautiful Conveying a Child’s Coffin, Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s classic portrayal of grief, Lemminkäinen’s mother, and – a personal favourite here at the Books from Finland office – Magnus von Wright’s evocative Annankatu Street on a Cold Winter’s Morning.

The Ateneum has few foreign works of art; in the Google Art collection now there are one Rodin, a Modigliani, a van Gogh and two Gauguins.

For love or money

30 June 1994 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Paratiisitango (‘Paradise tango’, WSOY, 1993). Introduction by Markku Huotari

The bishops’ dilemma

They are waiting for Blume in the front room of the office. On the sofa sits a man whom Blume has never learned to like. He himself chose and appointed the man, for a job not insignificant from the point of view of the company. Blume has good reasons for the appointment. If he employed only men he liked, the business would have gone bankrupt years ago.

Reinhard Kindermann gets up from the sofa and waits in silence while Blume hangs up his overcoat. Mrs Giesler stands next to Blume. She does not try to help her superior take off his coat, for she knows from experience that he would not tolerate it, but the old man does allow her to stand next to him and wait in silence, like a servant expressing submission. More…

The devil has no clothes

31 December 2006 | Fiction, poetry

Poems from Idealrealisation (‘The ideal sale’, 1929)

Stockings

V

I thought:

it was a person,

but it was her clothes

and I didn't know

that it doesn't matter

and that clothes can be very

beautiful

Books from Finland to take archive form

22 May 2015 | In the news

The following is a press release from the Finnish Literature Society.

The Finnish Literature Society is to cease publication of the online journal Books from Finland with effect 1 July 2015 and will focus on making material which has been gathered over almost 50 years more widely available to readers.

Books from Finland, which presents Finnish literature in English, has appeared since 1967. Until 2008 the journal appeared four times a year in a paper version, and subsequently as a web publication. Over the decades Books from Finland has featured thousands of Finnish books, different literary genres and contemporary writers as well as classics. Its significance as a showcase for our literature has been important.

The major task of recent years has been the digitisation of past issues of the journal to form an electronic archive. The archive will continue to serve all interested readers at www.booksfromfinland.fi; it is freely available and may be found on the FILI website (www.finlit.fi/fili).

Much is written in English and other languages about Finnish literature: reviews, interviews and features appear in even the biggest international publications. The need for the presentation of our literature has changed. Among the ways in which FILI continues to develop its remit is to focus communications on international professionals in the book field, on publishers and on agents.

The reasons for ceasing publication of Books from Finland are also economic. Government aid to the Finnish literature information centre FILI, which has functioned as the journal’s home, has been cut by ten per cent.

Books from Finland was published by Helsinki University Library from 1967 to 2002, when the Finnish Literature Society took on the role of publisher. FILI has been the body within the Finnish Literature Society that has been responsible for the journal’s administration, and it is from FILI’s budget that the journal’s expeses have been paid.

Enquiries: Tuomas M.S. Lehtonen, Secretary General of the Finnish Literature Society, telephone +358 40 560 9879.

The pearl

30 December 1999 | Fiction, Prose

A short story from Tutkimusmatkailija ja muita tarinoita (‘The explorer and other stories’, Loki-kirjat, 1999)

My name is Jan Stabulas. I am one of the quietest and inconspicuous workers in our department store, this giant ant-heap swarming with people. No one really pays any attention to me, although I am on show all the time. My job is quite simple: to stand in the menswear department, dressed in fashionable clothes. Now that doesn’t take much, I have heard it said. Well, try it yourself. Try standing for ten hours, without moving, in an awkward, even an unnatural, position, wishing that the air conditioning would work when it was hot, or that it would be switched off when you can feel the draught cutting you to the marrow. Think how the customers stare at you as they pass by, like an object which they cannot buy, and consider your words once more. More…

Need to go?

23 June 2010 | This 'n' that

No traveller can avoid toilets, as the internet service about.com (run by the company that owns the New York Times) points out on its Scandinavia travel website.

No traveller can avoid toilets, as the internet service about.com (run by the company that owns the New York Times) points out on its Scandinavia travel website.

Thus, it may be reassuring to know that ‘the days of outhouses are numbered’, and in Finland there are no squat toilets, according to the experiences of the editor, Terri Mapes. (The concept of ‘Finlandic restrooms’, however, is a new one to us – as is, for that matter, the adjective ‘Finlandic’.)

However, under the title ‘Bad Things About Toilets in Finland’ you’ll be informed about the possibility of outhouses without running water, should you choose the option of wandering into the wildernesses. And as toilets at airports or train stations may occasionally smell bad, it is advisable to use the bathroom at your hotel, unless your needs are urgent of course. More…

Pen to paper

25 October 2012 | Articles, Non-fiction

Writing is ancient: the act of taking a stylus, a quill or a pen into one’s hand still feels powerful. Will we find a way of scrawling in space, to mark our individuality, wonders Teemu Manninen

It was my vacation, and I wanted to catch up on some fun writing projects, but because I didn’t want to depend on my devices (would we have wifi? would the batteries last?) or carry around too much extra stuff I bought a red notebook and wrote in black ink on white paper while sitting in cafes and restaurants with my wife.

Writing by hand got me – surprise – to thinking about handwriting in general. Etymologically, ‘writing’, from Old English writan, means scratching, drawing, tearing. In the original Hebrew, God does not simply fashion humans out of clay, he writes them: his word is his image, giving life to the letter of his meaning, the human being.

Writing is violence. It brings about vivid change in the matter of the world: in the age of clay tablets, the stylus was a carving instrument. During the age of ink, cutting the tip of the quill was, if we believe the early Renaissance manuals of handwriting, as precise and violent an act as cutting someone’s head off. More…

Not joined up

19 February 2015 | In the news

Photo: Brad Flickinger / CC BY 2.0

The news that Finnish schools are to stop teaching cursive writing, in favour of a new emphasis on touch typing and the most efficient way of composing a text message, has been widely reported in the British press.

But not in our household.

With three children – aged 13, 9 and 6 – all struggling, to a greater or lesser degree, to make sense of the curlicues of joined-up writing as it’s taught in British schools, the pressure to abandon school in London and move to Finland would be all but irresistible if they every got to hear the news.

With letter-forms that bear little resemblance to printed characters and a loopy style, apparently derived from old-fashioned copperplate, that few children are going to be able to master completely, let alone develop into an elegant mode of handwriting, joined-up handwriting remains for many an obstacle to, not a means of, communication.

Added to the benefits of Finnish schools my children already know about – the shorter working days, the lighter homework load, the absence of school uniforms, the good school meals, the outdoor breaks every hour – the news that not only will Finnish schoolchildren not be expected to develop good handwriting, but will be issued with tablets on which to practise their computer skills, would axe their enthusiasm for school at home in Britain.

For their mother, the puzzle remains how Finland manages to employ such child-friendly school policies and still remain close to the top of the global Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) assessments. The trick seems to be to recruit top-level graduates into well-run teacher training schemes, pay them well, and to trust them to do their job as teachers, without the mounds of paperwork and need for incessant testing that bedevil the job in Britain.

About the handwriting, my children will find out soon enough, when their friends in Finland come home carrying not exercise books but tablets.

But meanwhile, I’m keeping my fingers crossed they don’t see this piece.

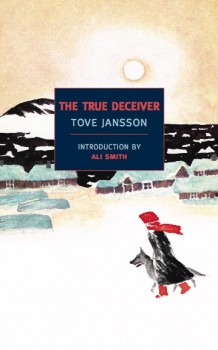

Best Translated Book Award 2011

13 May 2011 | In the news

Thomas Teal’s translation from Swedish into English of Tove Jansson’s novel Den ärliga bedragaren (Schildts, 1982), entitled The True Deceiver (published by New York Review Books, 2009), won the 2011 Best Translated Book Award in fiction (worth $5,000; supported by Amazon.com). The winning titles and translators for this year’s awards were announced on 29 April in New York City as part of the PEN World Voices Festival.

Thomas Teal’s translation from Swedish into English of Tove Jansson’s novel Den ärliga bedragaren (Schildts, 1982), entitled The True Deceiver (published by New York Review Books, 2009), won the 2011 Best Translated Book Award in fiction (worth $5,000; supported by Amazon.com). The winning titles and translators for this year’s awards were announced on 29 April in New York City as part of the PEN World Voices Festival.

Organised by Three percent (the link features a YouTube recording from the award ceremony, introducing the translator, Thomas Teal [fast-forward to 7.30 minutes]) at the University of Rochester, and judged by a board of literary professionals, the Best Translated Book Award is ‘the only prize of its kind to honour the best original works of international literature and poetry published in the US over the previous year’. ‘Subtle, engaging and disquieting, The True Deceiver is a masterful study in opposition and confrontation’, said the jury.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001), mother of the Moomintrolls, story-teller and illustrator of children’s books, translated into 40 languages, began to write novels and short stories for adults in her later years. Psychologically sharp studies of relationships, they are written with cool understatement and perception.

Quality writing will work its way into a wider knowledge (i.e. a bigger language and readership) eventually… even though occasionally it may seem difficult to know where exactly it comes from; in a review published in the London Guardian newspaper, the eminent writer Ursula K. Le Guin assumed Tove Jansson was Swedish.

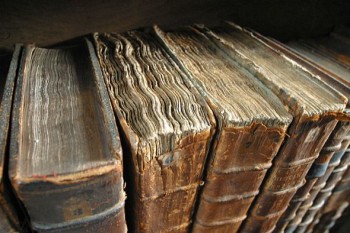

The coder’s Latin

30 October 2014 | Articles, Non-fiction

Pleasant interface still? Old book bindings (Merton College library, Oxford, UK). Photo: Wikipedia

Writing is arguably brain-control technology, notes our columnist Teemu Manninen. Writing might not be on its way out, at least not quite yet, he thinks, but the printed book might not stay with us for ever. And would that be a happier world?

When the future of literature is discussed, either here in Finland and elsewhere, topics usually revolve around changes in the economics and practicalities of reading, writing, and publishing: how will writers and publishers get paid, and how can readers find more books to read.

What is taken for granted in these instances is that literature itself will continue to be something that exists in a recognisable way – which itself of course implies that writing itself will remain a viable mass medium for the transmission of information over the transcendent, enormous, unfathomable gulfs of space and time, as it has been for thousands of years. More…

Second nature

15 February 2010 | Articles, Non-fiction

We hear a lot about how the internet is going to transform the reading and the marketing of books. But what about the act of writing? Teemu Manninen reports from the frontline of a new generation of authors for whom life has always been digital

We hear a lot about how the internet is going to transform the reading and the marketing of books. But what about the act of writing? Teemu Manninen reports from the frontline of a new generation of authors for whom life has always been digital

When we think of the future of publishing in these times of electronic reading devices, audiobooks, and the internet, when it seems as if the whole material being of literature is about to be transformed, we may ask how the marketing of books will change.

What happens when publishing goes online? How will authors cope with the new culture of the internet? More…

About us

8 January 2009 |

The Books from Finland online journal ceased operation on 1 July 2015, and no new articles will be published on the site.

A comprehensive online archive is available for readers to access. Brief extracts from Books from Finland may be quoted, provided that the source is cited.

If you wish to use longer extracts, please contact .

Books from Finland, an independent English-language literary journal, was aimed at readers interested in Finnish literature and culture. Its online archive constitutes a wide-ranging collection of Finnish writing in English: over 550 short pieces and extracts from longer works by Finnish authors were published from 1967 onwards.

Books from Finland featured classics as well as new writing, fiction and non-fiction, and other materials aimed at giving readers additional information on Finnish society and the wellsprings of Finnish literature. The target audience encompasses literary and publishing professionals, editors, journalists, translators, researchers, students, universities, Finns living abroad and everyone else with an interest in Finland and its literature.

Of course, publishing Finnish and Finland-Swedish literature in English requires skilled translators. Books from Finland’s editorial policy was always to use native English-speaking translators. In recent years David Hackston, Hildi Hawkins, Emily & Fleur Jeremiah, David McDuff, Lola Rogers, Neil Smith, Jill Timbers, Ruth Urbom and Owen Witesman translated for us.

Books from Finland was founded in 1967 and appeared in print format up to the end of 2008. From 2009 to 2015 it was an online publication. The journal’s archives have been fully digitised, and remaining issues will be made available in late 2015.

The Finnish Book Publishers’ Association (Suomen Kustannusyhdistys, SKY) began publishing the print edition of Books from Finland in 1967 with grant support from the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture. In 1974 the Finnish Library Association (Suomen Kirjastoseura) took over as publisher until 1976, when it was succeeded by the Helsinki University Library, which remained as the journal’s publisher for the next 26 years. In 2003 publishing duties were handed over to the Finnish Literature Society (Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, SKS) and its FILI division, which remained its home until 2015. The journal received financial assistance from the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture throughout its 48 years of existence.

The editors-in-chief of Books from Finland were Prof. Kai Laitinen (1976–1989), journalist and critic Erkka Lehtola (1990–1995), author Jyrki Kiiskinen (1996–2000), author and journalist Kristina Carlson (2002–2006), and journalist and critic Soila Lehtonen (2007–2014), who had previously been deputy editor. The journal was designed by artist and graphic designer Erik Bruun from 1976 to 1989 and thereafter by a series of graphic designers: Ilkka Kärkkäinen (1990–1997), Jorma Hinkka (1998–2006) and Timo Numminen (2007–2008).

In 1976 Marja-Leena Rautalin, the director of the Finnish Literature Information Centre (now known as FILI), became deputy editor of Books from Finland. She was succeeded by Anna Kuismin (neé Makkonen), a literary scholar. Soila Lehtonen served as deputy editor from 1983 to 2006. Hildi Hawkins, who had been translating texts for the journal since the early 1980s, held the post of London editor from 1992 until 2015.

The editorial board of Books from Finland was chaired from 1976 to 2002 by chief librarian Esko Häkli, from 2004 to 2005 by the Secretaries-General the Finnish Literature Society, Jussi Nuorteva and Tuomas M.S. Lehtonen, and from 2006 to 2015 by Iris Schwanck, director of FILI. Members of the board included literary scholars, journalists, authors and publishers.

This history of Books from Finland was compiled by Soila Lehtonen, who served as the journal’s deputy editor from 1983 to 2006 and editor-in-chief from 2007 to 2014. English translation by Ruth Urbom.