Search results for "david barrett"

The power game

30 June 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Puhua, vastata, opettaa (‘Speak, answer, teach’, 1972) could be called a collection of aphorisms or poems; the pieces resemble prose in having a connected plot, but they certainly are not narrative prose. Ikuisen rauhan aika (‘A time of eternal peace’, 1981) continues this approach. The title alludes ironically to Kant’s Zum Ewigen Frieden, mentioned in the text; ‘eternal peace’ is funereal for Haavikko.

In his ‘aphorisms’ Haavikko is discovering new methods of discourse for his abiding preoccupation: the power game. All organizations, he thinks, observe the rules of this sport – states, armies, businesses, churches. Any powerful institution wages war in its own way, applying the ruthless military code to autonomous survival, control, aggrandizement, and still more power. No morality – the question is: who wins? ‘I often entertain myself by translating historical events into the jargon of business management, or business promotion into war.’

‘What is a goal for the organization is a crime for the individual.’ Is Haavikko an abysmal pessimist, a cynic? He would himself consider that cynicism is something else: a would-be credulous idealism, plucking out its own eyes, promoting evil through ignorance. As for reality, ‘the world – the world’s a chair that’s pulled from under you. No floor’, says Mr Östanskog in the eponymous play. Reading out the rules of a mindless and cruel sport, without frills, softening qualifications, or groundless hopes, Haavikko is in the tradition of those moralists of the Middle Ages, who wrote tracts denouncing the perversity and madness of ‘the world’ – which is ‘full of work-of-art-resembling works of art, in various colours, book-resembling texts, people-resembling people’.

Kai Laitinen

Speak, answer, teach

When people begin to desire equal rights, fair shares, the right to decide for themselves, to choose

one cannot tell them: You are asking for goods that cannot be made.

One cannot say that when they are manufactured they vanish, and when they are increased they decrease all the time. More…

Poems

30 June 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Interview by Philip Binham

Birdmount

I hear a happy tale, it makes me sad:

no-one will remember me for long.

I will send a letter with nothing inside, the emptiness will reek

as the pines do, of fruit-peel and of smoke,

a scent only.

Here I have stayed a week, seven riverside days.

The river treads the mill, ah, treads the mill,

the river’s wide, this is a placid reach, the sky is near:

smoke, like the shadow of a birdflock passing, nothing else.

And now it is September:

there are more pine trees here, and more darkness too. More…

Lest your shadow fade

31 March 1987 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Jottei varjos haalistu (‘Lest your shadow fade’, 1987). Interview by Erkka Lehtola

‘… learn, then, to like yourself.

Dancing beside your shadow, laugh and play.

Dance always in the sunlight, lest your shadow fade.’J. Fr. Erlander, 1876 (Erika Kuovinoja’s grandfather)

‘Tis in life’s hardness that its splendour lies.’

J. Fr. E., 1890

Three days before the date fixed for the funeral, the minister directed his steps towards the home of the deceased, trying, as he walked, to compose his thoughts, which were full of righteous Lutheran anger. There were many good reasons for this. On the other hand, nothing that had happened in the past ought to make any difference, now that he was on his way to visit a house of mourning. A visit that called for the exercise of understanding, and even, if possible, kindness. It was a lot for anyone to expect, even of a clergyman. It was not by his own desire that he was paying this call: it was a matter of duty. And this time he was the protagonist. Petulantly, his shoes crunched the gravel. More…

A happy day

12 August 2010 | Fiction, Prose

‘Muttisen onni eli laulu Lyygialle’ (‘Muttinen’s happiness, or a song for Lygia’‚) a short story from Kuolleet omenapuut (‘Dead apple trees’, Otava, 1918)

‘Quite the country gentleman, eh, what, hey?’ says Aapeli Muttinen the bookseller. ‘Like the poet Horace – if I may humbly make the comparison, eh, dash it? With his villa at Tusculum, or whatever the place was called, given to him by Maecenas, in the Sabine hills, wasn’t it? – dashed if I remember. Anyway, he served Maecenas, and I serve – the public, don’t I? Selling them books at fifty pence a copy.’

Muttinen’s Tusculum is his little plot of land in the country. A delightful place, comforting to contemplate when the first signs of summer are beginning to appear, after a winter spent in town in the busy pursuit of Mammon, under skies so grey that the wrinkles on Muttinen’s forehead must have doubled in number. A summer paradise of idleness… More…

The nursemaid

Lapsenpiika (‘The nursemaid’), a short story, first published in the newspaper Keski-Suomi in December, 1887. Minna Canth and a new biography introduced by Mervi Kantokorpi

‘Emmi, hey, get up, don’t you hear the bell, the lady wants you! Emmi! Bless the girl, will nothing wake her? Emmi, Emmi!’

At last, Silja got her to show some signs of life. Emmi sat up, mumbled something, and rubbed her eyes. She still felt dreadfully sleepy.

‘What time is it?’

‘Getting on for five.’

Five? She had had three hours in bed. It had been half-past one before she finished the washing-up: there had been visitors that evening, as usual, and for two nights before that she had had to stay up because of the child; the lady had gone off to a wedding, and baby Lilli had refused to content herself with her sugar-dummy. Was it any wonder that Emmi wanted to sleep? More…

The Conference

31 December 1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Alamaisen kyyneleet (‘Tears of an underdog’, Karisto 1970). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Dr Smith said that he did not believe that any immediate threat of an invasion from Space was likely to arise for some time. Observations to date had given no support to the view that any such preparations had been put in hand. Technically they were of course ahead of us, but in his opinion there was no cause for panic. Nor could he endorse the widespread but naive assumption that any confrontation with beings from Space must inevitably lead to war. If human beings had reason to feel threatened, it was from each other that the chief threat came. He urged the Conference to work for a situation in which every country would be preparing for peace rather than for war. He said he had no wish to sound sardonic, but that he had noticed that when war was prepared for, it was usually war that ensued. More…

The lake

30 June 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Järvi (‘The lake’), a short story, 1915. Introductions by Kai Laitinen and Pekka Tarkka

I travel the world, not out of any desire for adventure, but because that is the way things have happened. The best of my wanderings are in obscure, tucked-away regions, where life is humdrum and pitched in a low key. There I have no need to stave off nostalgia for the past by leading a hectic life: my days go by in stolid succession from season to season, I am an ordinary unimportant individual among all the rest. For long stretches of time my life does not strike me as being either dull or bright; I derive a certain satisfaction from its very emptiness. It is as though I were, by degrees and to the best of my ability, paying off a kind of debt. More…

Aphorisms

31 December 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Aphorisms from Pahojen henkien historia (‘A history of evil spirits’, 1986). Markku Envall’s essay on aphorism

Do not set out in the wrong mood, at the wrong moment, for the wrong place.

Learn to distinguish these from one another, for it is an impossible task.

Do not admit to changes in yourself, say rather that your associates vary.

And that your relationships are changeable. But do not say this of yourself.

Not knowing a person should not be regarded as sufficient reason for not making his acquaintance. More…

The personal and the political

In his new collection, Claes Andersson (born 1937) – poet, pianist and politician – takes a look at what human existence is about: excess, apathy, greed, devotion, freedom, and the simple pleasures of everyday life (see the introduction)

Poems from Lust (‘Desire’, Söderströms, 2008), translated by David McDuff and David Hackston

A Finnish translation, by Jyrki Kiiskinen, is entitled Ajan meno (WSOY, 2008)

(easter)

Despite the prognoses of the Earth's imminent warming today April 8 it is cold enough to make one’s teeth chatter In a few weeks I will turn seventy, my ninth grandchild August (Siiri's younger brother) was born two months ago and the tenth is on the way

The return of Orpheus

31 December 1992 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

from Hid (‘Coming here’, Söderströms, 1992). A Valley in the Midst of Violence, a selection of poems by Gösta Ågren translated by David McDuff, was published by Bloodaxe Books of Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1992. Introduction by David McDuff

No poet can endure

being dead, a sojourn without

meaning and method. He needs

order and rhythm. His poems

are really laws. He

always turns back

from the underworld, which resembles

the everyday.

The darkness hides the screams

around him, when

the way begins. The sun is

only black heraldry, only

a cavern in the sky

of stone, and he sees

it, without being blinded. More…

Between shadow and sunlight

31 December 1996 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Homecoming (translated by David McDuff, published by Carcanet Press, 1993)

It was hopeless trying to keep the window on the yard side clean

Perhaps it was an advantage not to see clearly,

roofs and chimneys, indeed, even the sky became friendly

seen from this renunciation. When it rained

the water formed streets of narrow drops, almost silver-coloured.

I considered them closely.

What use I should have for them I did not know.

*

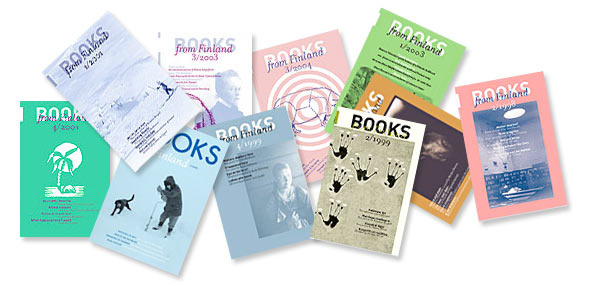

About us

8 January 2009 |

The Books from Finland online journal ceased operation on 1 July 2015, and no new articles will be published on the site.

A comprehensive online archive is available for readers to access. Brief extracts from Books from Finland may be quoted, provided that the source is cited.

If you wish to use longer extracts, please contact .

Books from Finland, an independent English-language literary journal, was aimed at readers interested in Finnish literature and culture. Its online archive constitutes a wide-ranging collection of Finnish writing in English: over 550 short pieces and extracts from longer works by Finnish authors were published from 1967 onwards.

Books from Finland featured classics as well as new writing, fiction and non-fiction, and other materials aimed at giving readers additional information on Finnish society and the wellsprings of Finnish literature. The target audience encompasses literary and publishing professionals, editors, journalists, translators, researchers, students, universities, Finns living abroad and everyone else with an interest in Finland and its literature.

Of course, publishing Finnish and Finland-Swedish literature in English requires skilled translators. Books from Finland’s editorial policy was always to use native English-speaking translators. In recent years David Hackston, Hildi Hawkins, Emily & Fleur Jeremiah, David McDuff, Lola Rogers, Neil Smith, Jill Timbers, Ruth Urbom and Owen Witesman translated for us.

Books from Finland was founded in 1967 and appeared in print format up to the end of 2008. From 2009 to 2015 it was an online publication. The journal’s archives have been fully digitised, and remaining issues will be made available in late 2015.

The Finnish Book Publishers’ Association (Suomen Kustannusyhdistys, SKY) began publishing the print edition of Books from Finland in 1967 with grant support from the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture. In 1974 the Finnish Library Association (Suomen Kirjastoseura) took over as publisher until 1976, when it was succeeded by the Helsinki University Library, which remained as the journal’s publisher for the next 26 years. In 2003 publishing duties were handed over to the Finnish Literature Society (Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, SKS) and its FILI division, which remained its home until 2015. The journal received financial assistance from the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture throughout its 48 years of existence.

The editors-in-chief of Books from Finland were Prof. Kai Laitinen (1976–1989), journalist and critic Erkka Lehtola (1990–1995), author Jyrki Kiiskinen (1996–2000), author and journalist Kristina Carlson (2002–2006), and journalist and critic Soila Lehtonen (2007–2014), who had previously been deputy editor. The journal was designed by artist and graphic designer Erik Bruun from 1976 to 1989 and thereafter by a series of graphic designers: Ilkka Kärkkäinen (1990–1997), Jorma Hinkka (1998–2006) and Timo Numminen (2007–2008).

In 1976 Marja-Leena Rautalin, the director of the Finnish Literature Information Centre (now known as FILI), became deputy editor of Books from Finland. She was succeeded by Anna Kuismin (neé Makkonen), a literary scholar. Soila Lehtonen served as deputy editor from 1983 to 2006. Hildi Hawkins, who had been translating texts for the journal since the early 1980s, held the post of London editor from 1992 until 2015.

The editorial board of Books from Finland was chaired from 1976 to 2002 by chief librarian Esko Häkli, from 2004 to 2005 by the Secretaries-General the Finnish Literature Society, Jussi Nuorteva and Tuomas M.S. Lehtonen, and from 2006 to 2015 by Iris Schwanck, director of FILI. Members of the board included literary scholars, journalists, authors and publishers.

This history of Books from Finland was compiled by Soila Lehtonen, who served as the journal’s deputy editor from 1983 to 2006 and editor-in-chief from 2007 to 2014. English translation by Ruth Urbom.

The matchstick

31 March 1998 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction

A fairy-tale, first published in the literary yearbook Svea (Stockholm) in 1879. Introduction by Esa Sironen

The matchstick lay for the first time in its new box on the factory table and thought about what had happened to it so far during its short life. It could still dimly remember how the big aspen tree had grown on the river bank, how it had been felled, sawed, and finally planed into many thousand small splinters of which the match was one. After that, it had been sorted into piles and rows with its friends, dipped in horrible melting pans, put out to dry, dipped again and finally placed in the box. This was not really a remarkable fate, nor a great heroic deed. But the match had acquired a burning desire to do something in the world. Its body was made from the timorous aspen, which is constantly a-quiver because it is afraid that the faint evening breeze might grow into a gale and tear it up by the roots. It so happened, however, that the match’s head had been dipped in stuff that makes one ambitious and want to shine in the world, and so a struggle developed, as it were, between body and head. When the inflammable head, fizzing in silence, cried: ‘Rush out now and do something!’ the cautious body always had an objection ready, and whispered: ‘No, wait a little, ask and find out if it’s time yet!’ More…