Search results for "2010/02/2011/04/2009/09/what-god-said"

On the make

31 December 2007 | Fiction, Prose

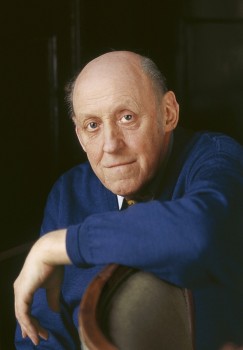

Extracts from the novel Benjamin Kivi (WSOY, 2007). Introduction by Lauri Sihvonen

Benjamin Kivi alias Into Penger, the 1930s

What was Kuihkä worth? What were this little man and his sons worth? What was I worth?

I drove where the little man told me to, with no lights, through a densely populated area. I could only see half a meter in front of me, trying to sense the bends and curves in the road and still keep Tallus’ car in good shape. When we got to the woods I turned on the lights and glanced at the little man sitting next to me. He was stuffing a handkerchief into his sleeve like an old housewife. The top of his head was sweating. He brushed his hair back and shoved his cap down on his head.

I had two hours to think as I drove, but it felt like a few minutes. If I didn’t drive the car, someone else would have, everything would happen just like the little man had planned, and I wouldn’t know anything about Kuihkä. What was I going to do, watch while he was thrown to the wolves? Kuihkä rescued me once. Was it meant to be that I should drive the car? Was I meant to change the course of events? How many coincidences can there be in one lifetime, and what do they signify? If events weren’t random, then what the hell was I supposed to do? More…

Poems

31 December 1985 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Introduction by George C. Schoolfield

Birds of passage

Ye fleet little guests of a foreign domain,

When seek ye the land of your fathers again?

When hid in your valley

The windflowers waken,

And water flows freely

The alders to quicken,

Then soaring and tossing

They wing their way through;

None shows them the crossing

Through measureless blue,

Yet find it they do.

Unerring they find it: the Northland renewed,

Where springtime awaits them with shelter and food,

Where freshet-melt quenches

The thirst of their flying,

And pines’ rocking branches

Of pleasures are sighing,

Where dreaming is fitting

While night is like day,

And love means forgetting

At song and at play

That long was the way. More…

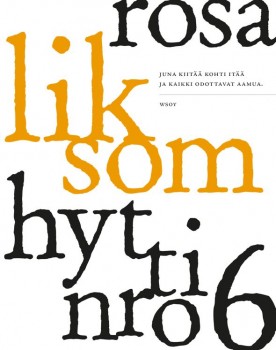

Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011

1 December 2011 | In the news

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011, worth €30,000, is Rosa Liksom, for her novel Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY): read translated extracts and an introduction of the author here on this page.

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011, worth €30,000, is Rosa Liksom, for her novel Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY): read translated extracts and an introduction of the author here on this page.

The prize was awarded on 1 December. The winner was selected by the theatre manager Pekka Milonoff from a shortlist of six.

‘Hytti nro 6 is an extraordinarily compact, poetic and multilayered description of a train journey through Russia. The main character, a girl, leaves Moscow for Siberia, sharing a compartment with a vodka-swilling murderer who tells hair-raising stories about his own life and about the ways of his country. – Liksom is a master of controlled exaggeration. With a couple of carefully chosen brushstrokes, a mini-story, she is able to conjure up an entire human destiny,’ Milonoff commented.

Author and artist Rosa Liksom (alias Anni Ylävaara, born 1958), has since 1985 written novels, short stories, children’s book, comics and plays. Her books have been translated into 16 languages.

Appointed by the Finnish Book Foundation, the prize jury (journalist and critic Hannu Marttila, journalist Tuula Ketonen and translator Kristiina Rikman) shortlisted the following novels: Kallorumpu (‘Skull drum’, Teos) by Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, William N. Päiväkirja (‘William N. Diary’, Otava) by Kristina Carlson, Huorasatu (‘Whore tale’, Into) by Laura Gustafsson, Minä, Katariina (‘I, Catherine’, Otava) by Laila Hirvisaari, and Isänmaan tähden (‘For fatherland’s sake’, first novel; Teos) by Jenni Linturi.

Rosa Liksom travelled a great deal in the Soviet Union in the 1980s. She said she hopes that literature, too, could play a role in promoting co-operation between people, cultures and nations: ‘For the time being there is no chance of some of us being able to live on a different planet.’

Chronicles of crisis

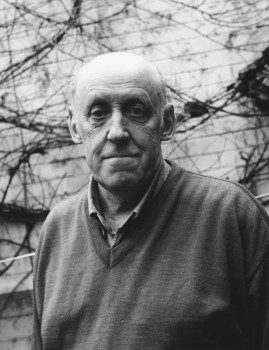

31 December 1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Books from Finland presents here an extract from Dyre prins, a novel by the Finland-Swedish writer Christer Kihlman that is to be published in 1983 by Peter Owen of London under the title Sweet Prince, in a translation by Joan Tate.

Christer Kihlman (born 1930) first became known as a poet; but, after publishing two collections of poetry, he turned to novels. He has been branded a merciless scourge of the bourgeoisie. Equally important in his writing, however, are his masterly psychological analyses, his examination of the myriad aspects of the human personality, his sovereign disregard for taboos and his unflagging search for the truth. His books are about crises – the conflict between the generations, between the individual and society, between opposing political ideologies, between homosexual and heterosexual love. As Ingmar Svedberg remarked in an extensive appreciation of Kihlman’s work that appeared in Books from Finland 1-2/1976, ‘In his perceptive moral analyses, his exploration of the depths of human destructiveness and degradation, Kihlman is sometimes reminiscent of Faulkner.’ Since 1970, Kihlman has published three revealing autobiographical works, two of them dealing with his encounter with South America; Dyre prins, first published in 1975, represents a brief interlude of fiction.

The extract printed below is accompanied with a personal appreciation of the novel by its English translator, Joan Tate

Grandfather’s astonishing revelation gave me a new perspective on my life. I had suddenly been given a concrete, genuine foundation for both my hatred and my self-esteem. In a way I took the story of my origins as an extreme confirmation of the rightness of the Communist interpretation of reality, and at the same time it gave me a wonderful, dazzling sensation of being someone, despite everything, of having a place in a meaningful human perspective of time, despite everything, of being a link, however modest, in the historical family tradition. I did not need to found a dynasty; I already belonged to a dynasty, if only a minor branch. One was less important than the other, and even if the two experiences were irreconcilable and contradictory, they existed all the same in the same consciousness, contained within the same consciousness, my consciousness. I, Donald Blad! More…

A walk on the West Side

16 March 2015 | Fiction, Prose

Hannu Väisänen. Photo: Jouni Harala

Just because you’re a Finnish author, you don’t have to write about Finland – do you?

Here’s a deliciously closely observed short story set in New York: Hannu Väisänen’s Eli Zebbahin voikeksit (‘Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits’) from his new collection, Piisamiturkki (‘The musquash coat’, Otava, 2015).

Best known as a painter, Väisänen (born 1951) has also won large readerships and critical recognition for his series of autobiographical novels Vanikan palat (‘The pieces of crispbread’, 2004, Toiset kengät (‘The other shoes’, 2007, winner of that year’s Finlandia Prize) and Kuperat ja koverat (‘Convex and concave’, 2010). Here he launches into pure fiction with a tale that wouldn’t be out of place in Italo Calvino’s 1973 classic The Castle of Crossed Destinies…

Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits

Eli Zebbah’s small but well-stocked grocery store is located on Amsterdam Avenue in New York, between two enormous florist’s shops. The shop is only a block and a half from the apartment that I had rented for the summer to write there.

The store is literally the breadth of its front door and it is not particularly easy to make out between the two-storey flower stands. The shop space is narrow but long, or maybe I should say deep. It recalls a tunnel or gullet whose walls are lined from floor to ceiling. In addition, hanging from the ceiling using a system of winches, is everything that hasn’t yet found a space on the shelves. In the shop movement is equally possible in a vertical and a horizontal direction. Rails run along both walls, two of them in fact, carrying ladders attached with rings up which the shop assistant scurries with astonishing agility, up and down. Before I have time to mention which particular kind of pasta I wanted, he climbs up, stuffs three packets in to his apron pocket, presents me with them and asks: ‘Will you take the eight-minute or the ten-minute penne?’ I never hear the brusque ‘we’re out of them’ response I’m used to at home. If I’m feeling nostalgic for home food, for example Balkan sausage, it is found for me, always of course under a couple of boxes. You can challenge the shop assistant with something you think is impossible, but I have never heard of anyone being successful. If I don’t fancy Ukrainian pickled cucumbers, I’m bound to find the Belorussian ones I prefer. More…

Mary Bloom

31 December 1983 | Archives online, Drama, Fiction

Introduction by Väinö Vainio

‘Is Mary Bloom about a revivalist religious meeting, a party political conference at which a new leader is born, or a rock concert? These are among the things that have been suggested. I don’t know. I don’t hope for restraint in the imaginations of those who choose.to interpret my work, although I observe it myself. The work of a writer is a part of life, it is an individual and collective experience that seeks, finds, takes and uses its materials like a motor machine. For those who create it the drama is real, as in the theatre, for the duration of the performance.’ Jussi Kylätasku

Characters

Mary Bloom

Martha, a doctor

Otto, a preacher

Disabled veteran

Serenity, his wife

Alcoholic

Cold Cal, a prisoner

Blind man, Deaf Wife More…

Year of the cat

13 November 2014 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Kissani Jugoslavia (‘Yugoslavia, my cat’, Otava 2014). Introduction by Mervi Kantokorpi

I met the cat in a bar. And he wasn’t just any cat, the kind of cat that likes toy mice or climbing trees or feather dusters, not at all, but entirely different from any cat I’d ever met.

I noticed the cat across the dance floor, somewhere between two bar counters and behind a couple of turned backs. He loped contentedly from one place to the other, chatting to acquaintances in order to maintain a smooth, balanced social life. I had never seen anything so enchanting, so alluring. He was a perfect cat with black-and-white stripes. His soft fur gleamed in the dim lights of the bar as though it had just been greased, and he was standing, firm and upright, on his two muscular back paws.

Then the cat noticed me; he started smiling at me and I started smiling at him, and then he raised his front paw to the top button of his shirt, unbuttoned it and began walking towards me. More…

Government Prize for Translation 2011

24 November 2011 | In the news

María Martzoúkou. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

The Finnish Government Prize for Translation of Finnish Literature of 2011 – worth € 10,000 – was awarded to the Greek translator and linguist María Martzoúkou.

Martzoúkou (born 1958), who lives in Athens, where she works for the Finnish Institute, has studied Finnish language and literature as well as ancient Greek at the Helsinki University, where she has also taught modern Greek. She was the first Greek translator to publish translations of the Finnish epic, the Kalevala: the first edition, containing ten runes, appeared in 1992, the second, containing ten more, in 2004.

‘Saarikoski was the beginning,’ she says; she became interested in modern Finnish poetry, in particular in the poems of Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983). As Saarikoski also translated Greek literature into Finnish, Martzoúkou found herself doubly interested in his works.

Later she has translated poetry by, among others, Tua Forsström, Paavo Haavikko, Riina Katajavuori, Arto Melleri, Annukka Peura, Pentti Saaritsa, Kirsti Simonsuuri and Caj Westerberg.

Among the Finnish novelists Martzoúkou has translated are Mika Waltari (five novels; the sixth, Turms kuolematon, The Etruscan, is in the printing press), Väinö Linna (Tuntematon sotilas, The Unknown Soldier) and Sofi Oksanen (Puhdistus, Purge).

María Martzoúkou received her award in Helsinki on 22 November from the minister of culture and sports, Paavo Arhinmäki. Thanking Martzoúkou for the work she has done for Finnish fiction, he pointed out that The Finnish Institute in Athens will soon publish a book entitled Kreikka ja Suomen talvisota (‘Greece and the Finnish Winter War’), a study of the relations of Finland and Greece and the news of the Winter War (1939–1940) in the Greek press, and it contains articles by Martzoúkou.

The prize has been awarded – now for the 37th time – by the Ministry of Education and Culture since 1975 on the basis of a recommendation from FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange.

Helsinki Book Fair 2011

2 November 2011 | In the news

President Toomas Hendrik Ilves at the Book Fair: Viro is Estonia in Finnish. Photo: Kimmo Brandt/The Finnish Fair Corporation

The Helsinki Book Fair, held from 27 to 30 October, attracted more visitors than ever before: 81,000 people came to browse and buy books at the stands of nearly 300 exhibitors and to meet more than a thousand writers and performers at almost 700 events.

The Music Fair, the Wine, Food and Good Living event and the sales exhibition of contemporary art, ArtForum, held at the same time at Helsinki’s Exhibition and Convention Centre, expanded the selection of events and – a significant synergetic advantage, of course – shopping facilities. Twenty-eight per cent of the visitors thought this Book Fair was better than the previous one held in 2010.

According to a poll conducted among three hundred visitors, 21 per cent had read an electronic book while only 6 per cent had an e-book reader of their own. Twenty-five per cent did not believe that e-books will exceed the popularity of printed books, and only three per cent believed that e-books would win the competition.

Estonia was the theme country this time. President Toomas Hendrik Ilves of the Republic of Estonia noted in his speech at the opening ceremony: ‘As we know well from the fate of many of our kindred Finno-Ugric languages, not writing could truly mean a slow national demise. So publish or perish has special meaning here. Without a literary culture, we would simply not exist and we have known this for many generations, since the Finnish and Estonian national epics Kalevala and Kalevipoeg. – During the last decade, more original literature and translations have been published in Estonia than ever before. And we need only access the Internet to glimpse the volume of text that is not printed – it is even larger than the printed corpus. We live in an era of flood, not drought, and thus it is no wonder that as a discerning people, we do not want to keep our ideas and wisdom to ourselves but try to share and distribute them more widely. The idea is not to try to conquer the world but simply, with our own words, to be a full participant in global literary culture, and in the intellectual history and future of humankind.’

Finland meets Estonia: authors Sofi Oksanen and Viivi Luik in discussion. Photo: Kimmo Brandt/The Finnish Fair Corporation

Out of this world

31 December 1996 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Virkamatka (‘Business travel’, Otava, 1996). Introduction by Jyrki Kiiskinen

I spent a couple of weeks alone at home that summer. My brother was at camp and my father on a business trip. Bored one rainy day, I opened up their last game on the computer. They had been going on about it for weeks.

I began from the beginning, A splendid start: texts backed by imaginative visions, Then darkness. In the middle of it a gold-coloured, glimmering dot. Nothing else. I waited for a long time. Nothing else, I waited. Nothing. Then I pressed the computer’s space-bar. The dot exploded and the explosion filled the entire screen. From its centre swarmed familiar patterns, Diagrams of atomic nuclei, electrons, radiation. More…

Cityscapes

23 February 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Photographer Stefan Bremer’s home town, Helsinki, provides endless inspiration, material and atmospheric. For forty years Bremer has been recording views of the maritime city, its changing seasons, its cultural events, its people. These images are from his new book – entitled, simply, Helsinki (Teos, 2012)

City kids: day-care outing in Töölönlahti park. Photo: Stefan Bremer, 2010

When I was a child, Helsinki seemed to me a grey and sad town. Stooping, quiet people walked its broad streets. The colours of the houses had been darkened by coal smoke over the years, and new buildings were coated a depressing grey.

A lot has since changed. Today, Helsinki is younger than it was in my youth. More…

Brighter than darkness

30 June 2002 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Eksyneet (‘The lost’, WSOY, 2001). Interview by Markus Määttänen

It was a white tiled wall. Too white. Sterile. He wondered how long he had been looking at it. In any case long enough to have forgotten it was a wall. It had changed into a vacuum opening up before him and then shrunk into a tunnel through whose irresistible suction he had hurtled toward the painful images of the past. The past. Yesterday. Almost yesterday. He had stared at the nocturnal entrance, clearly divided in two by the street lamps, and not just that, but now saw only a lifeless and, in its lifelessness, repellant wall. He sighed, rubbed his numb face, pushed himself off the floor and stood up.

The life of a lonely friend

30 September 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Bo Carpelan. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

Extracts from Bo Carpelan‘s novel Axel, ‘a fictional memoir’ (1986). In his preface to the novel Bo explains how he ‘found’ Axel.

Preface

In the 1930s I came across the name of Axel Carpelan (1858-1919), my paternal grandfather’s brother, in Karl Ekman’s Jean Sibelius and His Work (1935). In the bibliography, the author briefly mentions quotes from letters in the book addressed to Axel Carpelan, ‘who belonged to the Master’s most intimate circle of friends, and in musical matters was his constant confidant. Sibelius commemorated their friendship by dedicating his second symphony to him’. I had never heard Axel’s name mentioned in my own family.

Many years after Karl Ekman, the original incentive for the novel about Axel arose through Erik Tawaststjerna’s biography of Sibelius, in which Axel is portrayed in the second volume (1967) of the Finnish edition, and whose life came to an end in Part IV (1978). From early 1970s onwards, I started notes for Axel’s fictional diary from to 1919. It is not known whether Axel himself ever kept a diary. I relied as muchas possible on all the available facts. These increased when I was given access to letters exchanged between Axel and Janne from the year 1900 onwards. It became the story of the hidden strength a very lonely and sick man, and of a friendship in which the give and take both sides was far greater than Axel himself could ever have imagined.

Hagalund, June 1st, 1985

Bo Carpelan

![]()

1878, Axel’s diary

15.1.

On my twentieth birthday, I remember the young Wolfgang; ‘Little Wolfgang has no time to write because he has nothing to do. He wanders up and down the room like a dog troubled by flies’. However, that dog achieved a paradise. I have learnt yet one more piece of wisdom: ‘It is my habit to treat people as I find them; that is the most rewarding in the long run’. More…