Search results for "2010/02/2011/04/2009/09/what-god-said"

The Cheap Contractor

30 June 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Kauan kukkineet omenapuut (‘Long-blossoming apple trees’, 1982). Introduction by Arto Seppälä

The men who delivered the hot-water cylinder offered to do the installation as well. I asked how much it would be. They lolled about a bit, exchanged a few private looks, pretended to be thinking. Then one of them fired off a sum. It was three times the quotation I’d already had. They didn’t even look at the location. I told myself I wouldn’t even go to the end of the road with big-dealers like these.

The same evening I rang up ‘a little man’ and told him he could get started as soon as it suited him.

The cheap contractor turned up a couple of days later, driving an elderly van into the yard. I went out. He’d sat himself down in a garden chair near the white lilacs. The morning sun only partially reached there; so half his body was in shade, looking colder than the sunny half. More…

Horse sense

2 February 2012 | Essays, Non-fiction

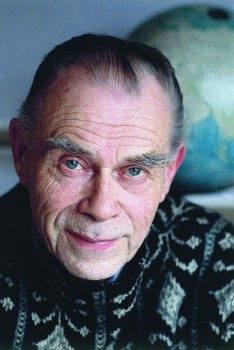

The eye that sees. Photo: Rauno Koitermaa

In this essay Katri Mehto ponders the enigma of the horse: it is an animal that will consent to serve humans, but is there something else about it that we should know?

A person should meet at least one horse a week to understand something. Dogs help, too, but they have a tendency to lose their essence through constant fussing. People who work with horses often also have a dog or two in tow. They patter around the edge of the riding track sniffing at the manure while their master or mistress on the horse draws loops and arcs in the sand. That is a person surrounded by loyalty.

But a horse has more characteristics that remind one of a cat. A dog wants to serve people, play with humans – demands it, in fact. With a dog, a person is in a co-dependent relationship, where the dog is constantly asking ‘Are we still US?’ More…

Moving on

30 June 2003 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the short story ‘Tunnin kuvat’ (‘One-hour processing’, from the collection Vapiseva sydän, ‘Tremulous heart’, Tammi, 2002). Introduction by Harry Forsblom

Last summer, when I was helping my brother with his move, he said I could take as many of his old LPs as I wanted. There were actually two of us on the job: his younger friend Timbe was along, and when we’d almost completely cleared out the flat and my brother’s two cellar closets (he’d rented an extra closet from the next-door flat, as he was submerging under the clobber lying around everywhere), he said the same to Timbe: ‘Just help yourself.’ The records we ourselves didn’t want would be chucked in the rubbish.

Jacob’s Dream

30 September 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Hänen olivat linnut (‘Hers were the birds’, 1967). Introduction by Pirkko Alhoniemi

‘It was Jacob’s Dream, Alma.’

How could she put it so Alma wouldn’t get hurt. Alma had ruined the surface of the painting. The pastor’s widow stood nervously in front of the window and tried to say what she’d had on her mind for several days but couldn’t quite come out with. When Alma went out of the house, the pastor’s widow would wander through the rooms and check on things. And the painting wasn’t the only object in danger, but also the birds. Their feathers were ruffled because Alma kept wiping them with a wet rag. How could she put it.

‘Alma.’

Alma turned to look at her.

‘It’s called Jacob’s Dream.’ More…

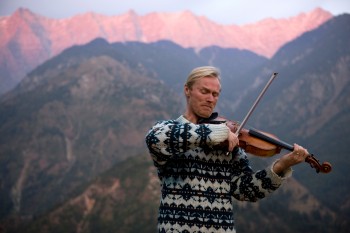

Teemu Kupiainen & Stefan Bremer

Music on the go

3 March 2010 | Extracts, Non-fiction

A little night music: Teemu Kupiainen playing in Baddi, India, as the sun sets. Photo: Stefan Bremer (2009)

It was viola player Teemu Kupiainen‘s desire to play Bach on the streets that took him to Dharamsala, Paris, Chengdu, Tetouan and Lourdes. Bach makes him feel he is in the right place at the right time – and playing Bach can be appreciated equally by educated westerners, goatherds, monkeys and street children, he claims. In these extracts from his book Viulun-soittaja kadulla (‘Fiddler on the route’, Teos, 2010; photographs by Stefan Bremer) he describes his trip to northern India in 2004.

In 2002 I was awarded a state artist’s grant lasting two years. My plan was to perform Bach’s music on the streets in a variety of different cultural settings. My grant awoke amusement in musical circles around the world: ‘So, you really do have the Ministry of Silly Walks in Finland?’ a lot of people asked me, in reference to Monty Python. More…

Man and boy

31 December 2006 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Kansallismaisema (‘National landscape’ Tammi, 2006). Introduction by Tuomas Juntunen

Plans were afoot to establish boys’ camps across the country. This was an experiment, a chance to test the water, to be a pioneer. Here was the opportunity to be the first in line to conquer the Wild West, just as many a brave cowboy had done in years gone by. The Ministry of General Affairs planned to put all 15-year-olds to work for the duration of the summer holidays. Casual labourers were often even younger. Our task was to ascertain a suitable minimum age. In addition, special camps were planned for those not suited to normal work camps. In the summers to come the youth of Finland would be fully employed. Weren’t we in fact driven by the same desire, Tikka had wondered. We both cared about the next generation. We wanted to root out their deficiencies so that they would be able to face life’s challenges to the full. More…

Dinner with Marie

30 June 2008 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Marie (WSOY, 2008). Introduction by Tuomas Juntunen

For once, Marie decided to plan a dinner without the same old roast beef, boiled potatoes, peas, red wine and berry kissel. And particularly no game. The thought of rabbit reminded her of the hunting trip to Porpakka, the hounds puking up rabbit skins onto the parquet floor, the smell of singed birds, the feathers that turned up even weeks later in a corner of the kitchen, the buckshot in the goose that broke her tooth. Mind you, she had to admit that brown sauce was quite good, especially as an aspic. She had tasted a spoonful once the morning after it was made, when Martta had gone out to buy milk and Marja was cleaning the drawing room, and then Martta had come back quite suddenly, and Marie had panicked and swallowed it the wrong way and had a fit of coughing. ‘Good heavens,’ Martta had said, ‘what’s the matter? I just came back to get my purse. I forgot it on the sideboard.’

The true reason for the plan was that she wanted to show them what a real French formal dinner was like, how much better it was. She planned the menu secretly for months, first in her mind, then in writing, at her bedroom dressing table – the only place she had to herself, although the door wouldn’t lock – at first on wrapping paper, which she later burnt in the tiled stove in the dining room when no one was home. More…

Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2010

19 November 2010 | In the news

A massive tome running to 1,000 pages by Vesa Sirén, journalist and music critic of the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper, features Finnish conductors from the 1880s to the present day. On 18 November it became the recipient of the 2010 Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction by the Finnish Book Foundation, worth €30,000.

A massive tome running to 1,000 pages by Vesa Sirén, journalist and music critic of the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper, features Finnish conductors from the 1880s to the present day. On 18 November it became the recipient of the 2010 Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction by the Finnish Book Foundation, worth €30,000.

The choice, from six shortlisted works, was made by economist Sinikka Salo. Suomalaiset kapellimestarit: Sibeliuksesta Saloseen, Kajanuksesta Franckiin (‘Finnish conductors: from Sibelius to Salonen, from Kajanus to Franck’) is published by Otava.

The other five works on the shortlist were Itämeren tulevaisuus (‘The future of the Baltic Sea’, Gaudeamus) by Saara Bäck, Markku Ollikainen, Erik Bonsdorff, Annukka Eriksson, Eeva-Liisa Hallanaro, Sakari Kuikka, Markku Viitasalo and Mari Walls; the Finnish Marshal C.G. Mannerheim’s early 20th-century travel diaries, Dagbok förd under min resa i Centralasien och Kina 1906–07–08 (‘Diary from my journey to Central Asia and China 1906–07–08’, Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland & Atlantis), edited by Harry Halén; Vihan ja rakkauden liekit. Kohtalona 1930-luvun Suomi (‘Flames of hatred and love. 1930s Finland as a destiny’, Otava) by Sirpa Kähkönen; Suomalaiset kalaherkut (‘Finnish fish delicacies’, Otava) by Tatu Lehtovaara (photographs by Jukka Heiskanen) and Puukon historia (‘A history of the Finnish puukko knife’, Apali) by Anssi Ruusuvuori.

What about me?

30 September 2008 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Mitä onni on (‘What happiness is’, Otava, 2008)

I was lying on the sofa watching Sports Roundup. The ski jumpers were flying at Zakopane. When I go one day, I want the cantor to play the Sports Roundup theme on the harmonium and the pallbearers to look on like skiing judges down into the pit.

‘I have an idea,’ Liisa said, sitting down at the other end of the sofa. I muted the television and adopted a focused expression. I focused on thinking about my expression.

‘Finnish happiness,’ Liisa pronounced solemnly. ‘I’ll illustrate, and you write.’

‘A book again,’ I said and turned the sound back on. They were reading off the women’s basketball scores now. Liisa waited patiently. I was disarmed enough by this that I turned the television off. More…

Digging for gold

30 June 1989 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Antti Tuuri has found his theme in the life of Finnish émigré communities and their experience in what used to be called ‘the New World’. Uusi Jerusalem (‘The New Jerusalem’, 1988), is about the Finns who migrated to Canada during the Depression, only to find that their utopian dreams had no basis in reality. In the following extract the narrator finds himself and his fellow mineworkers in the middle of the forest at night, on the way by foot to the Kirkland Lake gold mines, where they are going to be strikebreakers. The novel, an ironical tale of life in a new land, follows on from Pohjanmaa (‘Ostrobothnia’, 1982), Talvisota (‘The Winter War’, 1984), Ameriikan raitti (‘The American road’, 1986).

The train pulled up at Swastika station, many a mile from Kirkland Lake, and Hamina said we’d have to press on by foot from the station to the town.

Swastika, he said, meant the crooked cross, but he didn’t know whether there were any of those German Adolf-fanciers around, who were so keen on the sign. He was certain, in fact, the town had got its name long before anyone in Germany had heard of Adolf or his swastika.

We asked why we had to walk from here to the town. Hamina said we’d got to walk because even in Canada vehicles didn’t drive through the backwoods; moreover, it wasn’t a good idea to walk along the Kirkland Lake road: we might meet up with the kind of guys who’d make our arrival at Kirkland Lake seem very unwelcome. More…

The rocket

30 September 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Raketen (‘The rocket’), a novella from the collection Den segrande Eros (‘Eros triumphant’), 1912. Introduction by George C. Schoolfield

The sun shone straight in through the veranda’s little windows that made the whole ‘villa’ resemble a hothouse. With a sigh, Elsa let the morning paper fall to the floor; she had gotten halfway through the classified ads: ‘Three lads wish to correspond with likeminded lasses.’ ‘If Mr Söders-m does not fetch his effects, left as bond for unpaid rent, within a week, they will be regarded as our property, and his name will be published in toto.’ Now she could stand no more. The air seemed to come from a bakeoven. Listlessly, she watched two flies as they flicked the ceiling paper in their humming dance of love. It seemed as though knives were being thrust into the back of her head; that was the way her sick headaches began. A long walk might stop it, she knew, but she felt too tired.

At last, she was able to make herself get up and open the door for some fresh air. But with the air she got a powerful smell of roasting pork from the baker’s villa; the yells of the children playing cops and robbers up on the rock were doubled in force. A nasty stabbing sensation began in Elsa ears. And so she decided to take a walk after all, but only to the steamboat jetty. More…

One hell of a time

31 December 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Lanthandlerskans son (‘Country shopkeeper’s son’, Söderströms, 1997). Brooklyn Bridge, Christmas Eve: Otto, a Finland-Swede, attempts to start a new life in 1930s America, where swindlers and even gangsters can, he finds, be duped – even Al Capone. Otto’s grandson listens to his story on tape

I have always loved that sight. A city that you see from the air at night, all lit up. It’s’ beautiful – and at the same time so frightening. I don’t really know how to describe it.

Well, it was Christmas Eve. I was wandering around New York. I had eaten at an automat. Do you know what that is? They don’t exist any more, but in the Twenties and Thirties they were common in America. It’s a cafe, but they didn’t have any staff or waiters, instead the walls were full of little glass boxes where the food was on display. You could select what you wanted – sandwiches and pies and salads, anything. Then you put your nickels and dimes in a slot beside the box and the glass opened and’all you had to do was take out the plate. I was fond of the automats. I liked just sitting there and watching other people eat, no one bothered about you, you were left alone and that suited me. When I’d finished eating I went outside again and somehow or other I wandered upon to Brooklyn Bridge. There was a lot of traffic, people were on their way home. Well, just as I was walking there alone in the company of my thoughts I heard someone shouting ‘Help! Help me!’ More…

Renaissance man

30 September 1990 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Bruno (WSOY, 1990)

Since her first collection of poems, which appeared in 1975, Tiina Kaila (born 1951 [from 2004, Tiina Krohn]) has published four children’s books and three volumes of poetry. Her novel Bruno is a fictive narrative about the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno, who was burned at the stake in 1600. It is the conflict inherent in her main character that interests Kaila: his philosophical and scientific thought is much closer to that of the present day than, for example, that of Copernicus, and it is this that led him to the stake; and yet he did never abandon his fascination for magic.

The novel follows Bruno on his journeys in Italy; France, Germany and England, where he is accompanied by the French ambassador, Michel de Castelnau. Bruno finds England a barbaric place: ‘…These people believe that it is enough that they know how to speak English, even though no one outside this little island understands a word. No civilised language is spoken here’

In the extract that follows, Bruno, approaching the chalk cliffs of Dover by sea, makes what he feels to be a great discovery: ‘Creation is as infinite as God. And life is the supremest, the vastest and the most inconceivable of all.’

![]()

I was leaning on the foredeck handrail, peering into a greenish mist. The bow was thrashing between great swells, blustering and hissing and shuddering like some huge wheezing animal: Augh – aagh – ho-haugh! Augh – aagh – ho-haugh!

Plenty of space had been reserved for our use on this new two-master cargo boat. Castelnau was transferring his whole family from France – his wife, his daughter, his servants, his library, his furniture, his past and me – to London, where, as you know, he had been appointed Ambassador of France. More…

Finlandia Junior Prize 2011

7 December 2011 | In the news

The musician Paula Vesala has chosen, from a shortlist of six, a book for young people by the poet Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen, Valoa valoa valoa (‘Light light light’, Karisto). The story, which is set at the time of the Chernobyl nuclear power station disaster, poetically describes the passion and pain of first love, longing for mother and death.

The musician Paula Vesala has chosen, from a shortlist of six, a book for young people by the poet Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen, Valoa valoa valoa (‘Light light light’, Karisto). The story, which is set at the time of the Chernobyl nuclear power station disaster, poetically describes the passion and pain of first love, longing for mother and death.

‘Not just what is told, but how it is told. The rythm and timbre of Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen’s language are immensely beautiful. Her phrases do not exist merely to tell the story, but live like poetry or song. Valoa valoa valoa does not incline toward young people from the world of adults; rather, its voice comes, direct and living, from painful, confusing, complex youth, in which young people should really be protected from adults and their blindness. I would have liked to read this book when I was fourteen,’ commented Vesala.

The other five shortlisted books were a picture book for small children, Rakastunut krokotiili (‘Crocodile in love’, Tammi) by Hannu Hirvonen & Pia Sakki, a philosophical picture book about being different and courageous entitled Jättityttö ja Pirhonen (‘Giant girl and Pirhonen’, Tammi) by Hannele Huovi and Kristiina Louhi; a dystopic story set in the 2300s, Routasisarukset (‘Sisters of permafrost’, WSOY), by Eija Lappalainen & Anne Leinonen; a novel about the war experiences of an Ingrian family, Kaukana omalta maalta (‘Far away from homeland’, WSOY) by Sisko Latvus and an illustrated book about gods and myths of the world, Taivaallinen suurperhe (‘Extended heavenly family’, Otava) by Marjatta Levanto & Julia Vuori.

The prize, awarded by the Finnish Book Foundation on 23 November, is worth €30,000.