Search results for "2010/02/2011/04/2009/09/what-god-said"

Everyday life at the Science Forum 2011

20 January 2011 | In the news

‘Everyday life’ in focus: scientific approaches. Picture: Elina Warsta

This year’s Science Forum took place in Helsinki between 12 and 16 January. This biennial science festival – which has existed in its current format since 1977 – invites a wide audience to lectures, debates, discussions and various other events where scholars introduce their branch of research and science. This time the theme was ‘Science and everyday life’.

The Science Forum is organised by the Federation of Finnish Learned Societies, the Finnish Academies of Sciences and Letters and the Finnish Cultural Foundation.

In Finnish, the word for ‘everyday life’ is arki. Professor of Consumer Economics Visa Heinonen defined arki as follows: ‘Scientifically arki cannot be defined undisputably. An individual experiences the everyday as a ‘stream’ of life. Arki is mostly the recurrence of the small basic elements of life and the constant renewal of the prerequisites of existence. The everyday contains much that is routine as well as small moments of joy. Carpe diem, seize the moment, might be a good guideline to life.’

Among the Forum’s topics were the everyday work of scientific research and its significance for the development of everyday life in society, dimensions of consumer culture, multicultural society, religion, the arts and the media, technological advances in food production and the built environment, future energy sources and the global economy.

The Science Forum attracted 18,000 visitors, in addition to the 3,000 who participated in the Forum via the Internet. The five most popular topics, or sessions, were those entitled ‘Good life’, ‘Ageing as a biological phenomenon’, ‘Nanotechnology changing everyday life’, ‘Sleep – a third of life’ and ‘Food and everyday chemistry’.

Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2011

24 November 2011 | In the news

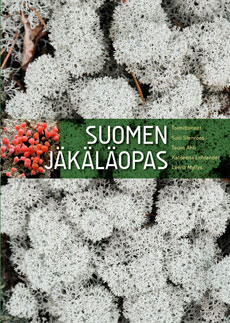

‘Scientific, aesthetic, timely: the work is all of these. A work of non-fiction can be both precisely factual and emotional, full of both information and soul. A good non-fiction book will surprise. I did not expect to be enthused by lichens, their variety and colours,’ declared Professor Alf Reen in announcing the winner of this year’s Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction on 17 November.

‘Scientific, aesthetic, timely: the work is all of these. A work of non-fiction can be both precisely factual and emotional, full of both information and soul. A good non-fiction book will surprise. I did not expect to be enthused by lichens, their variety and colours,’ declared Professor Alf Reen in announcing the winner of this year’s Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction on 17 November.

The winning work is Suomen jäkäläopas (‘Guidebook of lichens in Finland’), edited by Soili Stenroos & Teuvo Ahti & Katileena Lohtander & Leena Myllys (The Botanical Museum / The Finnish Museum of Natural History). The prize is worth €30,000.

The other works on the shortlist of six were the following: Kustaa III ja suuri merisota. Taistelut Suomenlahdella 1788–1790 [(‘Gustav III and the great sea war. Battles in the Gulf of Finland 1788–1790’, John Nurminen Foundation), written by Raoul Johnsson, with an editorial board consisting of Maria Grönroos & Ilkka Karttunen &Tommi Jokivaara & Juhani Kaskeala & Erik Båsk; Unihiekkaa etsimässä. Ratkaisuja vauvan ja taaperon unipulmiin (‘In search of the sandman. Solutions to babies’ and toddlers’ sleep problems’ ) by Anna Keski-Rahkonen & Minna Nalbantoglu (Duodecim); Operaatio Hokki. Päämajan vaiettu kaukopartio (‘Operation Hokki. Headquarters’ silenced long-distance patrol’), an account of a long-distance patrol strike in eastern Karelia during the Continuation War in 1944, by Mikko Porvali (Atena); Trotski (‘Trotsky’, Gummerus; biography) by Christer Pursiainen; and Lintukuvauksen käsikirja (‘Handbook of bird photography’) by Markus Varesvuo & Jari Peltomäki & Bence Máté (Docendo).

Turku, city of culture 2011

21 January 2011 | In the news

Passing the peace: citizens of Turku gathering to listen to the traditional declaration of peace at Christmas in front of the Cathedral. Photo: Esko Keski-oja

Since 1985, cities in the countries of the European Union have been chosen as European Capitals of Culture each year. More than 40 cities have been designated so far; a city is not chosen only for what it is but, more importantly, what it plans to do for year and also for what will remain after the year is over – the intention is that citizens and the local culture should profit from the investments made.

This year the two cities are Tallinn in Estonia and Turku, the oldest city and briefly (1809–1812) the capital of what was then the Grand Duchy of Finland, on the coast, 160 kilometres west of Helsinki. The pair will also co-operate in making this year a special one in their cultural lives.

The city of Turku declared its Cultural Capital year open on 15 January with a massive firework display glittering over the River Aura. This cultural capital enterprise, with a budget of 50 million euros and an ambitious programme will, hopefully, involve two million participants in the five thousand cultural events and occasions.

And he left the road

30 June 1983 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Three short stories from Maantieltä hän lähti (‘And he left the road’). Introduction by Eila Pennanen

And he left the road

And he left the road, walking straight ahead across fields and ditches, past barns and through bushes growing in the ditch. From the fields he went on to the forest, climbed a fence, walked past spruce and pine, juniper bushes and rocks, and came to the edge of a forest and to the swamp. He crossed the swamp, going through small groves of trees if they happened to be in his way. He went on walking rapidly across rivers, through forests, over seas and lakes, and through villages, and finally he came back to the very spot from which he had started walking straight ahead.

In the same way he walked at a right angle to the direction he had first taken and after that, a few times between those two directions. Every time he would start from the road and in the end would always come back to the road in the same direction as when he’d started off. On his rounds, after walking a bit, he would stop and look up every now and then, and each time he looked he would see the sky and sun or the moon and stars. More…

The attentive lover

31 December 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

In this short story, from his collection Pronssikausi (‘The bronze age’, 1988, on the Finlandia Prize shortlist in 1989), Martti Joenpolvi takes up the subject of the problematic transportation of a human cargo

He braked abruptly; the woman lurched forward, straining against the seat belt, and the car drove into the parking space. The only vehicle parked there was a solitary trailer loaded with timber: a resinous pulpwood-odour came wafting through their open window, so physical, it was as if someone were snooping into the car’s most intimate interior. When they stopped, they got the whiff of a yellow refuse bin, incubated in the heat of the day.

‘What’s up?’

‘We’ve got a problem.’ More…

Finlandia Junior Prize 2010

26 November 2010 | In the news

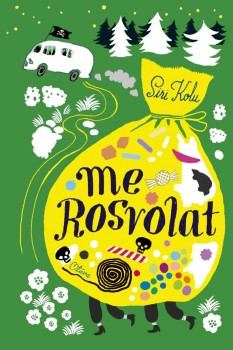

The Finlandia Junior Prize has gone to author Siri Kolu and illustrator Tuuli Juusela for the novel Me Rosvolat (‘Me and the Robbersons’, Otava); they will share the award of €30,000 (see the Prize jury assessments of the shortlist here). The winner was chosen by actor and writer Hannu-Pekka Björkman.

The Finlandia Junior Prize has gone to author Siri Kolu and illustrator Tuuli Juusela for the novel Me Rosvolat (‘Me and the Robbersons’, Otava); they will share the award of €30,000 (see the Prize jury assessments of the shortlist here). The winner was chosen by actor and writer Hannu-Pekka Björkman.

Awarding the prize on 25 November he said: ‘It caught my attention that in none of the six shortlisted children’s books are there any so-called nuclear families, at least not for long. The main characters constantly live and grow without something – the lack of parents or the attention of an adult is a serious matter to a child. However, in these books there is always someone who cares, not perhaps a stereotypical mom or dad, but an adult nevertheless.’ In Björkman’s opinion Me Rosvolat, with its rich language and a whiff of anarchy, presents the reader with moments of realisation and wonderment.

The books that sold

11 March 2011 | In the news

-Today we're off to the Middle Ages Fair. – Oh, right. - Welcome! I'm Knight Orgulf. – I'm a noblewoman. -Who are you? – The plague. *From Fingerpori by Pertti Jarla

Among the ten best-selling Finnish fiction books in 2010, according statistics compiled by the Booksellers’ Association of Finland, were three crime novels.

Number one on the list was the latest thriller by Ilkka Remes, Shokkiaalto (‘Shock wave‘, WSOY). It sold 72,600 copies. Second came a new family novel Totta (‘True’, Otava) by Riikka Pulkkinen, 59,100 copies.

Number three was a new thriller by Reijo Mäki (Kolmijalkainen mies, ‘The three-legged man’, Otava), and a new police novel by Matti Yrjänä Joensuu, Harjunpää ja rautahuone (‘Harjunpää and the iron room’, Otava), was number six.

The Finlandia Fiction Prize winner 2010, Nenäpäivä (‘Nose day’, Teos) by Mikko Rimminen, sold almost 54,000 copies and was fourth on the list. Sofi Oksanen’s record-breaking, prize-winning Puhdistus (Purge, WSOY; first published in 2008) was still in fifth place, with 52,000 copies sold.

Among translated fiction books were, as usual, names like Patricia Cornwell, Dan Brown and Liza Marklund.

In non-fiction, the weather, fickle and fierce, seems to be a subject of endless interest to Finns; the list was topped by Sääpäiväkirja 2011 (‘Weather book 2011’, Otava), with a whopping 140,000 copies. Number two was the Guinness World Records 2011, but with just 43,000 copies. Books on wine, cookery and garden were popular. A book on Finnish history after the civil war, Vihan ja rakkauden liekit (‘Flames of hate and love’, Otava) by Sirpa Kähkönen, made it to number 8 on the list.

The Finnish children’s books best-sellers’ list was topped by the latest picture book by Mauri Kunnas, Hurja-Harri ja pullon henki (‘Wild Harry and the genie’, Otava), selling almost 66,000 copies. As usual, Walt Disney ruled the roost in the translated fiction list.

The Finnish comics list was dominated by Pertti Jarla (his Fingerpori series books sold more than 70,000 copies, almost as much as Remes’ Shokkiaalto!) and Juba Tuomola (Viivi and Wagner series; both mostly published by Arktinen Banaani): between them, they grabbed 14 places out of 20!

Losing it

31 March 2002 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Jalat edellä (‘Feet first’, Otava 2001). Introduction by Kanerva Eskola

Once he had sat in the car for a while Risto could feel his thoughts slowly becoming clearer. Tero had been killed by a lorry. He couldn’t think particularly actively about it but perhaps he could have said it out loud. After all, people often say all kinds of things that they don’t think. Maybe even too often, he wondered and decided to have a go.

‘Tero is dead,’ he said and the words tasted of preserved cherries.

In the changing room at the swimming pool Risto noticed that his swimming trunks and towel were mouldy. He had forgotten to hang them up to dry after the last time he went swimming. That was a thousand years ago and now a bluish grey fur was growing on them. He examined the bitter smelling mould on his trunks; the fur was beautiful, smooth and silky like a rabbit’s coat. He gently stroked his trunks. I can use these for ice swimming, he decided, and began to chuckle quietly to himself.

The bully

31 March 1996 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Tulen jano (‘Thirst for fire’, Gummerus, 1995); power relations between doctor and patient in a situation where the past will not leave either alone

Nurmikallio, an apparently ordinary middle-aged man, came back again and again, and it seemed as if there would be no end to his story.

I listened to him patiently at first. Repeatedly he returned to the same subject. The form and emphases of the story changed, new memories emerged, but the gist was the same: he had failed in his life and believed that the root cause of his failure was a particular person, a childhood class-mate, a bully.

On the basis of his first visit I wrote a short character-sketch:

Intellectually average. Talkative, but by his own account solitary. Difficulties in human relationships, separated, no children. Electrician by profession, says he likes his work. Biggest problem obsessive attachment to childhood traumas.

And that’s all, I thought. But he was not to be so easily dismissed.

Arska

30 September 1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Kaksin (‘Two together’). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

A landlady is a landlady, and cannot be expected – particularly if she is a widow and by now a rather battered one – to possess an inexhaustible supply of human kindness. Thus when Irja’s landlady went to the little room behind the kitchen at nine o’clock on a warm September morning, and found her tenant still asleep under a mound of bedclothes, she uttered a groan of exasperation.

“What you do here this hour of day?” she asked, in a despairing tone. “You don’t going to work?”

Irja heaved and clawed at the blankets until at last her head emerged from under them.

“No,” she replied, after the landlady had repeated the question.

“You gone and left your job again?”

“Yep.” More…

Front-Line Tourists

30 September 1976 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Nahkapeitturien linjalla (‘On the tanners’ line’, 1976)

Paavo Rintala (born 1930) published his first novel in 1954 and since then has brought out a new book almost every year. A merciless critic of the myths surrounding certain national figures and events, he has written about Marshal Mannerheim, against attempts to glorify war, and the ‘inevitability’ of Finland’s involvment in the German Barbarossa plan. He has made considerable use of reportage technique to produce anti-war documentaries and in more recent years worked with international subjects.

His books have been widely translated and are popular in East and West Europe. Paavo Rintala’s novel Sissiluutnantti (‘Commando Lieuenant’, Otava 1963) and its reception were the subject of a book by the ltterary critic Pekka Tarkka (Paavo Rintalan saarna ja seurakunta. ‘Paavo Rintala’s sermon and congregation’, Otava 1966). Paavo Rintala is chairman of the Finnish Peace Committee. The passage below is taken from Nahkapeitturien linjalla (‘On the tanners’ line’, Otava 1976) in which he again turns his attention to the war years. Rintala looks at the events of the years leading up to the war and the course of the war itself through the eyes of many different people – from the leading politicians of the day to the ordinary soldier.

The novel has already been acclaimed as the monument to the ‘unknown soldier’ of the Winter War.

![]()

Hessu duly presented himself at the Viipuri office of the Army Information Department (Visitors’ Escort Section), where it was implied that the expected visitors were Very Important People and that a singular privilege was being conferred upon Hessu and such front-line troops that the party might visit. Although His Excellency Field-Marshal Mannerheim made it a rule never to allow front-line visits by ordinary journalists or even by special correspondents, these gentlemen were, it seemed, such influential people that H.E. had agreed to their visit without demur. “You understand, Padre, what a great responsibility this will be for you? These are very high-up people.” More…

The report

30 September 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Kesä ja keski-ikäinen nainen (‘Summer and the middle-aged woman’) Introduction by Margareta N. Deschner

Dear Colleague,

First of all, I want to thank you and your wife for the pleasant evening I and my wife had in your summer villa in August. Briitta (since we are old acquaintances: with two i’s and two t’s, remember?) especially wants me to mention that she will never forget the half moon climbing the hill behind your sauna, surprising us with its speed. The next time we looked it was half-way up the sky! Without doubt, your fine tequila had something to do with the matter, one shouldn’t forget that. Even so, it was quite a show, just like the time a bunch of us guys had gone skiing and you bragged that you had arranged for the barn to catch fire. I hope that you and your wife – I mean Alli – will be able to visit us next winter and taste a superb Mallorca red wine called Comas, which we brought home. It is by far the best red I have ever tasted and indecently cheap to boot. I hope you will come soon. The wine won’t keep indefinitely, as you well know. We’ll save it for you. So thanks again.

Looking back on a dark winter

31 December 1989 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the autobiographical novel Talvisodan aika (‘The time of the Winter War’), the childhood memoirs of Eeva Kilpi. During the winter of 1939–40 she was an 11-year old-schoolgirl in Karelia when it was ceded to the Soviet Union and the population evacuated

Time is the most valuable thing

we can give each other

War’s coming.

One day my father comes out with the familiar words in a totally unfamiliar way, while we’re sitting round the kitchen table eating, or just starting to eat.

He says to mother, as if we simply aren’t there, as if we don’t need to bother, or as if listening means not understanding. Or perhaps they’ve simply no other chance to speak to each other, as father’s always got to be off hunting, or on his way to the station, and mother’s always cooking. More…

In with the new?

17 December 2010 | Letter from the Editors

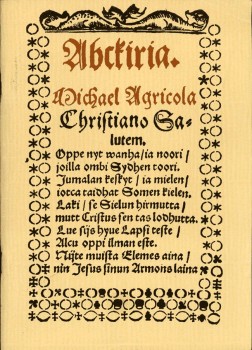

Abckiria (‘ABC book’, 1543): the first Finnish book, a primer by the Reformation bishop Mikael Agricola, pioneer of Finnish language and literature

In August 2010 the American Newsweek magazine declared Finland (out of a hundred countries) the best place to live, taking into account education, health, quality of life, economic dynamism and political environment.

Wow.

In the OECD’s exams in science and reading, known as PISA tests, Finnish schoolchildren scored high in 2006 – and as early as 2000 they had been best at reading, and second at maths in 2003.

Wow.

We Finns had hardly recovered from these highly gratifying pieces of intelligence when, this December, we got the news that in 2009 Finnish kids were just third best in reading and sixth in maths (although 65 countries took part in the study now, whereas in 2000 it had been just 32; the overall winner in 2009 was Shanghai, which was taking part for the first time.)

And what’s perhaps worse, since 2006 the number of weak readers had grown, and the number of excellent ones gone down. More…

Hotel for the living

30 June 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Hotelli eläville (‘Hotel for the living’, 1983). Introduction by Markku Huotari

Raisa and Pertti are a married couple with three children, Katrielina, Aripertti and Artomikko. When she discovers she is to have another, whom she names Katjaraisa, Raisa decides to have an abortion, because another child, even if welcome, would now jeopardise her career – she has been offered a job with an international company at the very top of the advertising world. Raisa is the successful entrepreneur of the novel – on the one hand coldly calculating, without feeling, on the other superficially sentimental, perhaps the most startlingly ironic of the characters in Jalonen’s novel. His image of the brave new woman?

During her lunch hour Raisa took a walk via the laboratory, asked reception for the envelope and thrust it unregarded into her handbag. She was aware of her already knowing, but short of the envelope, there would as yet be no restrictions, nor were there any decisions that would have to be made. She had called Tom Eriksson, discussed yet again the same points and particulars, and ended tracing a finger over the two beautiful pictures on her wall. ‘The loveliest of seas has yet to be sailed’ and ‘I am life! For Life’s sake.’

She thought of Katjaraisa, her features, the palms the breadth of two fingers, just as Katrielina’s had been, and the same button-eyed gazing look as Katrielina. More…