Search results for "2010/02/2011/04/2009/10/writing-and-power"

Marjo Niemi: Ihmissyöjän ystävyys [The cannibal’s friendship]

8 May 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Ihmissyöjän ystävyys

Ihmissyöjän ystävyys

[The cannibal’s friendship]

Helsinki: Teos, 2012. 402 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-359-2

€27.80, hardback

Marjo Niemi’s third novel may be described with the adjective ‘intemperate’. The book’s narrator is a thirty-something woman who is inclined to ranting. A friend’s suicide drives her to depression, which breaks out in endless criticism of her friends’ lifestyles. Her tolerance is tested not only by her hedonistic friends but also by an entire continent: she wallows in endless diatribes about the history of Europe and its injustices. The bubbling text forms a meta-level, a book within a book. Only writing seems meaningful: ‘I am really not going to write about my life, because life is a ridiculous joke compared to literature.’ The Great Novel that is being built by the narrator gradually opens out into a story about a mental hospital psychiatrist and one of his patients who has suffered a loss of memory. The author sees her work as a ‘poetic allegory of Europe ‘, but it is also a study of friendship, guilt, envy, and the difficulty of doing good. Caricature of an almost grotesque kind is skilfully combined with straight talking in this clever contemporary novel. Niemi (born 1978) is a dramaturge by training.

Translated by David McDuff

Ecstasy rewarded

28 November 2013 | In the news

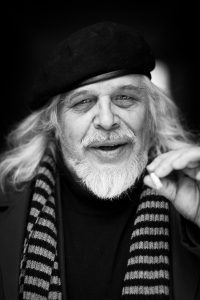

Erkka Filander. Photo: Virpi Alanen

On 14 November Helsingin Sanomat Literature Prize, the Helsinki newspaper’s prize for the best first work of the year, worth €15,000, was awarded for the 19th time.

The jury made its choice from 90 first works, and this time the prize was awarded to a youngest writer ever, the poet Erkka Filander (born 1993), for his collection Heräämisen valkea myrsky (‘The white storm of awakening’; available as a pdf at the home page of the publisher, Poesia).

According to the jury, this poetry is ‘ecstatic poetry, pulsing with the joy of living… there is no place in Filander’s poetry for cynicism or irony. Thus his writing appears, in the context of contemporary poetry, exceptionally open and sincere.’

Writes of passage

20 June 2013 | This 'n' that

Debating the word: participants at the Lahti Reunion. Photo: LIWRE

The 26th Lahti International Writers’ Reunion took place at Messilä Manor (some 120 km from Helsinki, on Lake Vesijärvi) from 15 to 18 June.

Chaired by Virpi Hämeen-Anttila and Joni Pyysalo, writers from more than 20 countries held discussions in Finnish, English and French.

This summer the theme was ‘Breaking walls’. ‘Problems demand answers, answers demand questions. If attitudes harden, arms talk, and everyone erects a wall around himself, where is literature in the equation? Is the highest wall right there inside the writer? Or is literature itself a protecting wall? What happens when walls break down?’

The first Writers’ Reunion took place in Lahti – first at Mukkula Manor – fifty years ago; more than a thousand writers, translators, critics and other professionals both Finnish and foreign have come to Lahti to discuss writing. The Reunion has always been open to the public as well.

The biannual Reunion began life in 1963, during the Cold War. Writers from both sides of the Iron Curtain met under the oaks of Mukkula. In the Reunion’s blog some participants and organisers share their experiences of the past; here, the meeting’s one-time international secretary Marianne Bargum recalls the late 1970s and early 1980s:

‘…following in the footsteps of the legendary publisher Erkki Reenpää who knew everybody and all languages, I did my best to persuade big stars to come to Mukkula. Some writers had difficulties when they realised that they were not as well known in Finland as in their own countries. The French poet Michel Deguy left after one day, very offended when nobody knew how big a name he was. (I met him in Paris some years later and he apologised.)

A scandal with huge political consequences came close when the French philosopher Bernard-Henry Lévy said some derogatory things about the Soviet head of state Brezhnev. The Russian delegate, Michael Baryshev, threatened to leave the conference, and Valentina Morozova, interpreter and politruk, had to phone the Soviet Embassy in Helsinki and explain that this was not very serious. The famous British critic and writer Al Alvarez did his best to calm down the antagonists in a panel.’

My own first personal experiences of this international fête (which could mean either wading in the mud on the way to the huge tent sheltering the discussions or basking in hot sunshine followed by the most gentle nightless nights), from the sunny summer of 1983: interviewing Salman Rushdie and Jayne Anne Phillips, among others, for the Finnish Broadcasting Company. Another time the bag containing some hundred copies of the latest issue of Books from Finland, fresh from the printing press, sat on a bus heading for Lahti while I sat on the one behind – which then broke down in the middle of the road, and this was before mobile phones. The driver did have a radio phone though, and the participants got their copies in time.

Soccer on the sand: Messilä beach. Photo: LIWRE

Among the traditions is a midnight football match between Finns and foreigners: the summer night is light and long. This time the result of the Finland against the rest of the world was convincing 6-3 to Finland.

New from the archives

11 May 2015 | This 'n' that

Sinikka Tirkkonen. Photo: Otava.

Short short prose from Sinikka Tirkkonen

This week, a short story by Sinikka Tirkkonen (born 1954), which we published in 1988 – a piece of confessional prose, ‘comfortless and depressed’, as Tero Liukkonen’s introduction has it, about life in a bleakly solipsistic world; the kind of writing, one’s inclined to say with hindsight, that only the young, or at least the not very old, have the leisure to produce.

‘Things are only right for me,’ says the unnamed narrator, ‘when they bring grief and distress in their train, when they pile up guilt feelings, harsh self-criticism and self-denial… All my life I’ll be deprived of something, always – full of cares, fears, terrible agonies. I’ve no right to live.’ There’s a train journey north, two women in a car on a long drive across Lapland, work, a husband’s unfaithfulness, pointlessness….

It’s beautifully done, though, with an appealing poetic minimalism. Enjoy!

![]()

The Books from Finland digitisation project continues, with a total of 388 articles and book extracts made available on our website so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

The snake

31 March 1998 | Fiction, Prose

In this horror story by the Finland-Swedish author Kjell Lindblad (born 1951), a man believes he is wandering among art installations in an apartment block – but the reality he is experiencing turns out to be much more sinister. From the collection of short stories Oktober-mars (‘October-March’, Schildts, 1997)

I only noticed the poster on the notice board in the vegetarian restaurant because it was so obviously different from the rest of the colourful items there, with their large headlines offering everything from Atlantic meditation to Zen ping-pong, together with promises of a new and fulfilled life in harmony with the soul and the cosmos. Poster is perhaps an overstatement it was a white sheet of paper with an egg-shaped oval in the middle. Inside the oval there was a horizontal row of seven numbers. For some reason, perhaps because the row of numbers was the only information on the piece of paper, it stuck in my memory and when I got home I had a compulsive desire to find out if it was a phone number. So I dialled the number and a tape-recorded voice that could have belonged to a man but equally well to a woman, said:

‘We bid you welcome. Please don’t write down the address just memorise it….’ More…

Bombast and the sublime

17 January 2013 | Reviews

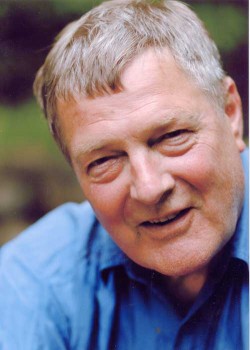

Torsten Pettersson

Torsten Pettersson

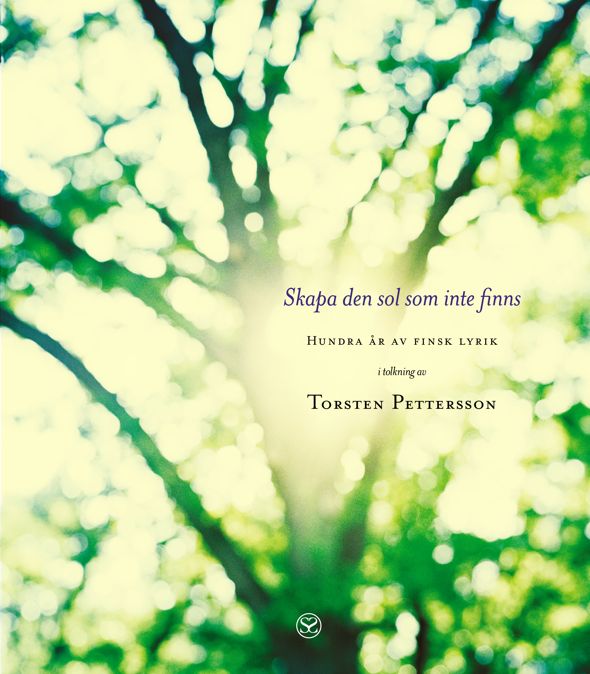

Skapa den sol som inte finns. Hundra år av finsk lyrik i tolkning av Torsten Pettersson

[Create the sun that is not there. A hundred years of Finnish poetry in Swedish translations by Torsten Pettersson]

Helsinki: Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 299 p.

ISBN 978-951-52-3034-8

€25, paperback

In the 1960s my mother sometimes used to amuse herself and us children by reciting, in Finnish, in our bilingual family, selected lines of verse from the half-forgotten poetry canon of her school years.

Eino Leino (died 1926) and the great tubercular geniuses Saima Harmaja, Uuno Kailas, Katri Vala and Kaarlo Sarkia (all dead by 1945) were familiar names to me as a child. Early on, I realised that their poetry was both profoundly serious and also slightly silly, just because of its high-flown seriousness. More…

Childhood revisited

31 March 2006 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Tämän maailman tärkeimmät asiat (‘The most important things of this world’, Tammi, 2005). Introduction by Jarmo Papinniemi

I was supposed to meet my mother at a café by the sea. She would be dressed in the same jacket that I had picked out for her five years ago. She would have on a high-crowned hat, but I wasn’t sure about the shoes. She loved shoes and she always had new ones when she came to visit. She liked leather ankle boots. She might be wearing some when she stepped off the train, looking out for puddles. She didn’t wear much make-up. I don’t remember her ever using powder, although I’m sure she did. I could describe her eye make-up more precisely: a little eye shadow, a little mascara, and that’s all.

That’s all? I don’t know my mother. As a child, I lived too much in my own world and it was only after I left home that I was able to look at her from far enough away to learn to know her. She had been so near that I hadn’t noticed her. More…

Prize for the best debut book

20 November 2014 | In the news

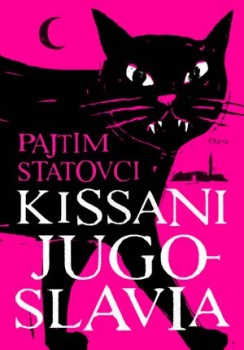

The Helsingin Sanomat literature prize for the best first work, written in Finnish, for 2014 was awarded on 13 November to Kosovo-born Pajtim Statovci, 24, for his novel Kissani Jugoslavia (‘Yugoslavia my cat’, Otava – see translated extracts here).

The Helsingin Sanomat literature prize for the best first work, written in Finnish, for 2014 was awarded on 13 November to Kosovo-born Pajtim Statovci, 24, for his novel Kissani Jugoslavia (‘Yugoslavia my cat’, Otava – see translated extracts here).

The choice was made by a five-strong jury from a total of 65 books. The prize, which was this year awarded for the 20th time, is worth €15,000.

Among the ten finalists were a collection of essays, three collections of poetry and six novels. According to the jury, Statovci’s novel, ‘drowns the reader, after a realistic description of events, in a dreamlike, lyrical vision. This kind of writing is not taught anywhere. The skill either resides in the writer or it doesn’t.’