Search results for "2010/02/let-us-eat-cake"

The funeral

31 December 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Hannu Salama’s short story Hautajaiset (‘The funeral’) – taking place in Pispala, Tampere – in the volume Kesäleski, ‘Summer widow’, was published in 1969. Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

On Tuesday Venla came round: as Sulo was being lowered into the grave Vihtori had had a heart attack. The next day a letter arrived from father: funeral on Sunday, and Gunilla and Timo want you to speak at the grave. I telegraphed back: ‘Vikki too close to me. Unable to speak.’ Outside the post office I realised I could have sent fifty words for the same money.

Irma ordered a flower arrangement. Did I want to put an inscription? Part of the last stanza of a revolutionary song went through my head:

Sowing makes the corn come into ear:

Hundredfold higher that happier age will be.

I said not to put anything, I’d say something at the grave if it seemed the thing to do. I told her to put mother’s, father’s and Heikki’s names on, and we’d take these off if they’d sent their own wreath. More…

When sleeping dogs wake

31 December 1994 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts rom the novel Tuomari Müller, hieno mies (‘Judge Müller, a fine man’, WSOY, 1994). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

In due course the door to the flat was opened, and a stoutish, quiet-looking woman admitted the three men, showed them where to hang their coats, indicated an open door straight ahead of them, and herself disappeared through another door.

After briefly elbowing each other in front of the mirror, the visitors took a deep breath and entered the room. The gardener was the last to go in. The home help, or whatever she was, brought in a pot of coffee and placed it on a tray, on which cups had already been set out, within reach of her mistress. The widow herself remained seated. They shook hands with her in tum. The mayor was greeted with a smile, but the bank manager and the gardener were not expected, and their presence came as a shock. She pulled herself together and invited the gentlemen to seat themselves, side by side, facing her across the table. They heard the front door slam shut: presumably the home help had gone out. More…

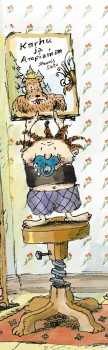

Growing together. New Finnish children’s books

28 January 2011 | Articles

Hulda knows what she wants! From the cover of a new picture book by Markus Majaluoma (see mini reviews*)

What to choose? A mum or dad buys a book hoping it will be an enjoyable read at bedtime – adults presume a book is a ‘good’ one if they themselves genuinely enjoy it, but children’s opinions may differ. Päivi Heikkilä-Halttunen reviews the trends in children’s literature published in Finland in 2010, and in the review section we’ve picked out a handful of the best on offer

Judging by the sheer number and variety of titles published, Finnish children’s and young people’s fiction is alive and well. If I had to describe the selection of books published in 2010 in just a few words, I would have to point to the abundance of titles and subject matters, and the awareness of international trends.

Since 2000 the number of books for children and young people published in Finland each year – including both translated and Finnish titles – has been well in excess of 1,500, and increasing, and this growth shows no signs of slowing down.

Little boys, ten-year-olds who don’t read very much and teenage boys, however, were paid very little attention last year. Although gender-specificity has never been a requirement of children’s fiction, boys are notably pickier when it comes to long, wordy books, especially those that might be considered ‘girly’. More…

Reindeer yoga?

15 July 2013 | This 'n' that

Human yoga wheel. Photo: Wikimedia

While Finnish politicians, just back at Parliament after their summer break, twiddle their thumbs in frustration as the nation faces darkening prospects for economic growth, Finland is being admired across the pond.

The Atlantic magazine took a long look at ‘the secrets of Finland’s success with schools, moms, kids – and everything’ (July 2013).

Olga Khazan reports: Finns enjoy long vacations, better school scores, unemployment insurance, paid parental leaves, cheap child care, education and medical services, and low infant mortality rates.

‘All of this adds up to the stress equivalent of living in what is essentially a vast, reindeer-fur-lined yoga studio.’

Whoa! Are we that happy in Finland? More…

Geneswing

30 June 2001 | Fiction, poetry

Poems from Tuulen vilja (‘Windcrop’, WSOY, 2000)

Longbeaked birds

created for the deepfunnelled gloxinia – everything exactly right.

The sport of colours, survival (though I always felt I was

sunset in the morning).

I walk over the living, the playful swing of genes,

uniqueness in splinters: capsules,

family trees, root systems, leafage.

In the geneswing little deviations of dimension,

as if I were perpetually outlining waves with my finger.

The primal miracle of seeds: I press

a mixture of summer flowers in the soil, exploding

a serial miracle. More…

Elina Brotherus & Riikka Ala-harja

The passing of time

2 March 2015 | Extracts, Fiction, Prose

In 1999 the Musée Nicéphore Niépce invited the young Finnish photographer Elina Brotherus to Chalon-sur-Saône in Burgundy, France, as a visiting artist.

After initially qualifying as an analytical chemist, Brotherus was then at the beginning of her career as a photographer. Everything lay before her, and she charted her French experience in a series of characteristically melancholy, subjective images.

Twelve years on, she revisited the same places, photographing them, and herself, again. The images in the resulting book, 12 ans après / 12 vuotta myöhemmin / 12 years later (Sémiosquare, 2015) are accompanied by a short story by the writer Riikka Ala-Harja, who moved to France a little later than Brotherus.

In the event, neither woman’s life took root in France. The book represents a personal coming-to-terms with the evaporation of youthful dreams, a mourning for lost time and broken relationships, a level and unselfpitying gaze at the passage of time: ‘Life has not been what I hoped for. Soon it will be time to accept it and mourn for the dreams that will never come true. Mourn for the lost time, my young self, who no longer exists.’

1999 Mr Cheval’s nose

AZ661748

19 September 2013 | Fiction, Prose

A short story from Novelli palaa! Matkanovelleja (‘The short story returns! Travel stories’, edited by Katja Kettu and Aki Salmela; WSOY, 2013)

Mum didn’t want to travel abroad. Mum wanted to tend her rose garden and her pea beds, which sloped down the hill towards the lake. In mum’s opinion, the view from the porch was the best view in the world.

Dad wanted to travel. He never got very far, because Mum wouldn’t go. Dad got as far as the neighbouring forest. In Mum’s opinion, there was no better long-haul destination than the lake at the bottom of the slope and the grove around the house, which was full of blueberries and raspberries and, in the spring, morel mushrooms.

In Dad’s opinion, the forest was full of mosquitoes and flies and ants and mites.

On the lake, the loons dived and called on late summer evenings, Mum thought it was the best sound in the world. Beautiful and harrowing, at the same time. The lamentations of the loon demonstrated that a living creature can be so completely happy that its cry is full of grief. Her children’s crying and whingeing and desire to go to the Linnanmäki funfair in Helsinki were, to Mum, a sign that they are ecstatically happy at home.

Little loons, Mum said to us. More…

Brighter than darkness

30 June 2002 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Eksyneet (‘The lost’, WSOY, 2001). Interview by Markus Määttänen

It was a white tiled wall. Too white. Sterile. He wondered how long he had been looking at it. In any case long enough to have forgotten it was a wall. It had changed into a vacuum opening up before him and then shrunk into a tunnel through whose irresistible suction he had hurtled toward the painful images of the past. The past. Yesterday. Almost yesterday. He had stared at the nocturnal entrance, clearly divided in two by the street lamps, and not just that, but now saw only a lifeless and, in its lifelessness, repellant wall. He sighed, rubbed his numb face, pushed himself off the floor and stood up.

Dinner with Marie

30 June 2008 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Marie (WSOY, 2008). Introduction by Tuomas Juntunen

For once, Marie decided to plan a dinner without the same old roast beef, boiled potatoes, peas, red wine and berry kissel. And particularly no game. The thought of rabbit reminded her of the hunting trip to Porpakka, the hounds puking up rabbit skins onto the parquet floor, the smell of singed birds, the feathers that turned up even weeks later in a corner of the kitchen, the buckshot in the goose that broke her tooth. Mind you, she had to admit that brown sauce was quite good, especially as an aspic. She had tasted a spoonful once the morning after it was made, when Martta had gone out to buy milk and Marja was cleaning the drawing room, and then Martta had come back quite suddenly, and Marie had panicked and swallowed it the wrong way and had a fit of coughing. ‘Good heavens,’ Martta had said, ‘what’s the matter? I just came back to get my purse. I forgot it on the sideboard.’

The true reason for the plan was that she wanted to show them what a real French formal dinner was like, how much better it was. She planned the menu secretly for months, first in her mind, then in writing, at her bedroom dressing table – the only place she had to herself, although the door wouldn’t lock – at first on wrapping paper, which she later burnt in the tiled stove in the dining room when no one was home. More…

Relative values

31 March 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the autobiographical novel Nurinkurin (‘Upside down, inside out’, WSOY, 2003). Interview by Anna-Leena Nissilä

The soldier rides on a scarf

waving a donkey

‘Now it’s your turn to go on,’ says my brother on the back seat, turning his head toward the window so that he can concentrate on his poetic muse.

Father looks in the mirror, wrinkling his face in pain. ‘The object, in other words, is of no significance to you. What happened to your case endings and your grammar?’

From the back seat we shout eagerly: ‘The poet has special privileges which are not accorded to others.’

Father shakes his head: ‘You can be creative, but silly content and broken language do not make poetry.’

‘Oh yes they do. Don’t disturb our creative spirit. When you speak, our connection with her is broken. Don’t cut off the source of our inspiration.’ More…

The storm

From the collection of short stories Tvåsamhet (‘Two alone’, Söderströms, 2005). Introduction by Tiia Strandén

A storm blows up during the night. As he lies in bed, not yet asleep, just lingering on the brink of falling, in that soft yet sensitive state where sounds seem to grow and get bigger, he can hear the clattering, hissing sound of the wind coming up out there and sweeping up everything not fastened down, capable of being put in motion. It scrapes against the roof and window, loosens leaves and pine needles which scud across the ground, and it whistles and whines round the chimney and the windows, and it even beats against the shed door, which Dad must have forgotten to shut properly before he came in. Before he stamped the mud off his boots in the front hall. Before he had a chance to pull the front door shut firmly as well, because Joakim can hear how he brings the storm into the hall with him, and it sweeps through the kitchen faster than he ever could have imagined. Joakim shuts his eyes tighter, even though he is no longer really awake, and he hears the powerful gust flap past Dad, who is still standing with his hand on the door handle, and then Mum starts shouting because the wind is slamming into the furniture and making dishes crash to the floor and making pots and pans do the same. When Dad starts shouting as well, Joakim lets go of the last little bit of wakefulness and lets himself sink down into the cradle of dreams to be carried along until the morning. It is the sun that wakes him, or maybe the sound of the telephone, because he wakes up just as it rings, but in any case it has stopped blowing, and the branches of the big lilac bush outside the window are completely still. More…

A walk on the West Side

16 March 2015 | Fiction, Prose

Hannu Väisänen. Photo: Jouni Harala

Just because you’re a Finnish author, you don’t have to write about Finland – do you?

Here’s a deliciously closely observed short story set in New York: Hannu Väisänen’s Eli Zebbahin voikeksit (‘Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits’) from his new collection, Piisamiturkki (‘The musquash coat’, Otava, 2015).

Best known as a painter, Väisänen (born 1951) has also won large readerships and critical recognition for his series of autobiographical novels Vanikan palat (‘The pieces of crispbread’, 2004, Toiset kengät (‘The other shoes’, 2007, winner of that year’s Finlandia Prize) and Kuperat ja koverat (‘Convex and concave’, 2010). Here he launches into pure fiction with a tale that wouldn’t be out of place in Italo Calvino’s 1973 classic The Castle of Crossed Destinies…

Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits

Eli Zebbah’s small but well-stocked grocery store is located on Amsterdam Avenue in New York, between two enormous florist’s shops. The shop is only a block and a half from the apartment that I had rented for the summer to write there.

The store is literally the breadth of its front door and it is not particularly easy to make out between the two-storey flower stands. The shop space is narrow but long, or maybe I should say deep. It recalls a tunnel or gullet whose walls are lined from floor to ceiling. In addition, hanging from the ceiling using a system of winches, is everything that hasn’t yet found a space on the shelves. In the shop movement is equally possible in a vertical and a horizontal direction. Rails run along both walls, two of them in fact, carrying ladders attached with rings up which the shop assistant scurries with astonishing agility, up and down. Before I have time to mention which particular kind of pasta I wanted, he climbs up, stuffs three packets in to his apron pocket, presents me with them and asks: ‘Will you take the eight-minute or the ten-minute penne?’ I never hear the brusque ‘we’re out of them’ response I’m used to at home. If I’m feeling nostalgic for home food, for example Balkan sausage, it is found for me, always of course under a couple of boxes. You can challenge the shop assistant with something you think is impossible, but I have never heard of anyone being successful. If I don’t fancy Ukrainian pickled cucumbers, I’m bound to find the Belorussian ones I prefer. More…

A view to a kill

31 December 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Klassikko (‘The classic’, WSOY, 1997). Pete drives an old Toyota Corolla without a thought for the small animals that meet their death under its wheels – or anything else, for that matter. Hotakainen describes the inner life of this environmental hazard with accuracy and precision

Pete sat in his Toyota Corolla destroying the environment. He was not aware of this, but the lifestyle he represented endangered all living things. The car’s exhaust fumes spread into the surroundings, its aged engine sweated oil onto the pavement, and malodorous opinions withered the willowherbs by the roadside. Granted that Pete was an environmental hazard, one must nevertheless ask oneself: how many people does one like him provide with employment? He leaves behind him a trail of despondent girlfriends who require the services of human relations workers, popular songwriters, and social service officials; during his lifetime, he spends tens of thousands of marks in automotive shops and service stations, on spare parts and small cups of coffee; he benefits the food industry by being a carefree purchaser of TV dinners and soft drinks. Pete is the perfect consumer, an apolitical idiot who votes with his wallet, the favorite of every government, even though no one seems interested in putting him to work, least of all himself. Every government, regardless of political power struggles, encourages its people to consume. Pete needs no encouragement, he consumes unconsciously, and one might ask: is there anything that he does consciously, the Greens and left-wingers would like him to? Does Pete make smart long-range decisions? Hardly.

The honey of the bee

30 June 2005 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from the collection Mitä sähkö on (‘What electricity is’ WSOY, 2004). Introduction by Jarmo Papinniemi

Five days before I was born my grandfather reached sixty-six. He’d always been old. The first image I have of him gleams like a knife on sunny spring-time snow: he was pulling me on my sledge over hard frost under a bright glaring-blue sky. In the Winter War a squadron of bombers had flown through the same blue sky on their way to Vaasa; the boys leapt into the ditches for cover, as if the enemy planes could be bothered to waste their bombs on a couple of kids. Be bothered? Wrong: kids were always the most important targets.

Now it’s summer, August, and I’m sitting on the grassy, mossy face of the earth, which is slowly warming in a sun that’s accumulated a leaden shadiness. I’m sitting on my grandfather’s land. It’s the time when the drying machines buzz. Even with eyes shut, you can sense the corn dust glittering in the sun. Even with eyes shut, you can take in the smell of the barn’s old wood, the sticky fragrance of the blackcurrants barrelled on its floor, the tins of coffee and the china dishes on the shelves, and the empty grain bins; there’s the cupboard Kalle made, with its board sides and veneered door, and the dust-covered trunk that was going to accompany my grandfather to another continent. The ticket was already hooked, but Grandfather’s world remained here for good. When Easter comes we’ll gather the useless junk out into the yard and burn it; Grandfather’s travel chest will rise skywards. Grandfather stands in the barn entrance, leaning on the doorpost. He’s dead. Over all lies a heavy overbearing sun. Beyond the field the river’s flowing silently in its deep channel. At night time its dark and warm. More…

A good day

30 June 2001 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

From Juomarin päiväkirjat (’A drunkard’s journals’, edited by Pekka Tarkka, Otava, 1999). Introduction by Claes Andersson

Iceland, Summer 1968

I don’t know how to describe what I see,

the lava’s colors; the afternoon green of the grass,

and I can’t tell if that white is buildings or snow.

The mountains are fortresses of the gods, and if

people’s construction projects irritate them

too much, they let the ground shake, volcanos

erupt and tum everything upside down, assign new sites

to houses and different routes for cars.

The gods’ noses itch when their breath

is caught in pipelines and

channeled into radiators and greenhouses.

Sheep tear the grass but horses

browse in a civilized manner.

Jónas does not believe in the gods, but he

is afraid of them, the gods are not pleased

with the Americans, who do not know

anything about the gods or history yet come here

and start interfering with the land

as if it were theirs.

*** More…