Search results for "2010/05/2009/09/what-god-said"

Two men in a boat

The meaning of life, Bob Dylan, the broken thermostat of the Earth, the authors Ambrose Bierce and Aleksis Kivi…. Two severely culturally-inclined men set out to row a boat some 700 kilometres along the Finnish coastline, and there is no shortage of things to discuss. Extracts from the novel Nyljetyt ajatukset (‘Fleeced thoughts’, Teos, 2014)

The red sphere of the sun plopped into the sea.

At 23.09 official summertime Köpi announced the reading from his wind-up pocket-watch.

‘There she goes,’ commented Aimo, gazing at the sunken red of the horizon, ‘but don’t you think it’ll pop back up again in another quarter of an hour, unless something absolutely amazing and new happens in the universe and the solar system tonight!’

Aimo pulled long, accelerating sweeps with his oars, slurped the phlegm in his throat, spat a gob overboard, smacked his lips and adjusted his tongue on its marks behind his teeth. There’s a respectable amount of talk about to come out of there, thought Köpi about his old friend’s gestures, and he was right.

‘Sure thing,’ was Aimo’s opening move, ‘darkness. Darkness, that’s the thing. I want to talk about it and on its behalf just now, now in particular, while we’re rowing on the shimmering sea at the lightest point of the summer. More…

Poems with rounded corners

30 September 1992 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Talvirunoja (‘Winter poems’, Art House, 1990) and Runot! Runot (‘Poems! Poems’, WSOY, 1992)

A prayer for the trees and the rocks

Around noon I start praying

for the trees and the rocks

to whom we have always been merciless.

What have we done?

What are we doing?

In the valley of the scribbling species

Man and Woman are two animal species, sufficiently close

to allow procreation.

They live in a cage called The Human Being,

in a place known as

the Valley of the Scribbling Species.

Woman is the more important animal

But Man built the cage.

An eye of the unseen

30 June 2007 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems and aphorisms by Aaro Hellaakoski. Introduction by Pertti Lassila

Evening

How tranquilly the evening’s darkening,

dusk deepening beneath the trees.

Consult the long alleyways of the skies

for the gift of this evening

and the cause of your ease.

But the waste! the pain and stress –

those reachings into secrets of the dark –

quarrying endlessness,

plummeting bottomlessness,

quizzing every question mark.

Why this rummaging into whence and why?

Empty let’s be. Open and free.

Let secrets come, or let them fly

away, diffuse like cloudscapes

or whisperings through a tree.

Eyes must glow as your spirits peer

through a wakeful cranny in where you are.

Only the silent have ears to hear.

When the doorstep feels the touch of a toe

only the vigilant’s door is ajar.

Huojuvat keulat (’Swaying prows’, 1945) More…

Notes related to pharmacist Pemberton’s holy nectar

Extracts from the novel Vådan av att vara Skrake (‘The perils of being Skrake’, Söderström & Co.; Isän nimeen, Otava, 2000)

At the time of Werner’s stay in Cleveland Bruno and Maggie had already been divorced for some years, and in an irreconcilable manner. But they were still interested in their grown-up son, each in their own way; Maggie wrote often, and Werner replied, he wrote at length, and truthfully, for he knew that Bruno and Maggie no longer communicated; to Maggie he could admit that he hated corporate law and bookkeeping, and to her he dared to talk about the raw music he had found on the radio station WJW, he wrote to her that the music of the blacks had body and that he had found a great record store, it was called Rendezvous and was situated on Prospect Avenue and there he had also bought a ticket for a blues concert, wrote Werner, he thought that Maggie would understand. More…

Still alive

31 March 2000 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Maa ilman vettä (‘A world without water’, Tammi, 1999)

The window opened on to a sunny street. Nevertheless, there was a pungent, sickbed smell in the room. There were blue roses on a white background on the wallpaper and, on the long wall, three landscape watercolours of identical size: a sea-shore with cliffs, a mountain stream, mountaintops. The room was equipped with white furniture and a massive wooden table. The television had been lifted on to a stool so that it could be seen from the bed.

The bed had been shifted to the centre of the room with its head against the rose-wall, as in a hospital. Between white sheets, supported by a large pillow, Sofia Elena lay awake in a half-sitting position. More…

Me and my shadow

Hotel Sapiens is a place where people are made to take refuge from the world that no longer is habitable to them; the world economy has fallen – like the House of Usher, in Edgar Allan Poe’s story – and with it, most of what is called a civilised society. A rapid synthetic evolution has taken humankind by surprise, and the world is now governed by inhuman entities called the Guardians. ‘Kuin astuisitte aurinkoon’ (‘As if stepping into the sun’) is a chapter from the novel Hotel Sapiens ja muita irrationaalisia kertomuksia (‘Hotel Sapiens and other irrational tales’, Teos, 2012), where several narrators tell their stories

The fog banks have dissipated; the sky is empty. I cannot see the sails or swells in its heights, nor the golden cathedrals or teetering towers. I would not have believed I could miss a fog bank, but that’s exactly what it’s like: its disappearance is making me uneasy. For all its flimsiness and perforations it was our protection, our shield against the sun’s fire and the stars’ stings. Now the relentlessly blazing sun has awakened colours and extracted shadows from their hiding places. The moist warmth has dried into heat and the Flower Seller’s herb spirals have dried up into skeletons. The leaves on the trees are full of bronze, sickly red and black spots. Though there is no wind and autumn is not yet here, they come loose as if of their own volition, as if they wanted to die.

This morning, as I was strolling up and down the park path as usual, I saw another shadow alongside my own.

– Ah, you’re back! I said. – I wondered what had happened to you after you lost your shadow; how did you manage to change into your own shadow yourself? More…

Underage

30 June 1999 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Leiri (‘Camp’, Otava 1972). Interview by Maija Alftan

In the dark and wet the tram seemed like a stale-smelling and badly-lit waiting room at a country station, its Post Office Savings Bank advertisement set out of reach of vandalising underage hands. The conductress was two-thirds out of sight behind her desk: a small person. I glanced at the time stamped on my ticket. My only timepiece.

It was the time of day when you can see your own face in the window and through to the outside as well. I stood in the doorway, hanging onto the bar. As the tram turned into the narrow canyon of Aleksanterinkatu, the street seemed like some kind of cellar. Fantastic, how the world darkens at the end of the year. And then, when it’s at its darkest, everything goes totally white. The low-slung cars seemed to be slinking round the tram’s feet. More…

The day of mourning

6 November 2014 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Katedraali (‘The cathedral’, Teos, 2014). Introduction by Mervi Kantokorpi

I am here now, at this funeral; I’m sitting on a puffy rococo chair which stands in the corner of this large living room – hall – on a Berber rug, one of a series of four pieces of furniture. The fourth is a curly-legged table, painted matt white. I wriggle like anything, trying to rid myself of my too-tight shoes. Fish thrash their tails in the same way. The lady in the dry cleaner’s told me she hates fish. She said that clothes that smell of fish and are brought into her shop make her shake with loathing but also bring her satisfaction because she can wash the awful stench away.

My shoes are impossibly small. They pinch my feet worse every moment. My back aches, too, despite the painkillers. You can’t swallow pills forever, so I just try to find a better position and put up with it. Finally my shoes leave my feet. I kick them underneath the table so that they can’t be seen. I can breathe again. In my shoes I felt as if I were sinking under the ground.

My father once showed me the Stephansdom catacombs. Thousands of people were buried here, before that, too, was forbidden by someone, he said. More…

Gorgonoids

31 March 1993 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Matemaattisia olioita tai jaettuja unia (‘Mathematical creatures, or shared dreams’, WSOY, 1992). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

The egg of the gorgonoid is, of course, not smooth. Unlike a hen’s egg, its surface texture is noticeably uneven. Under its reddish, leather skin bulge what look like thick cords, distantly reminiscent of fingers. Flexible, multiply jointed fingers, entwined – or, rather, squeezed into a fist.

But what can those ‘fingers’ be?

None other than embryo of the gorgonoid itself.

For the gorgonoid is made up of two ‘cables’. One forms itself into a ring; the other wraps round it in a spiral, as if combining with itself. Young gorgonoids that have just broken out of their shells are pale and striped with red. Their colouring is like the peppermint candies you can buy at any city kiosk. More…

A perfect storm

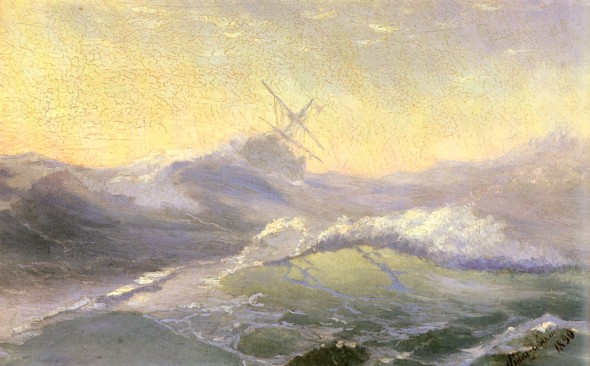

Bracing the waves. Ivan Aivazovsky, 1890.

According to Petri Tamminen, Finns are burdened by the need to succeed. Instead, he argues they should learn to fail better.

Part comedy, part tragedy, part picaresque novel, with a dash of Joseph Conrad – Tamminen’s new book, Meriromaani. Eräitä valoisia hetkiä merikapteeni Vilhelm Huurnan synkässä elämässä (‘A maritime novel. A few bright moments in Captain Vilhelm Huurna’s sombre life’, Otava, 2015) is set in an indeterminate seafaring past of the 18th or 19th century. It tells the story of the world’s most unsuccessful sea captain, Vilhelm Huurna who, one by one, sinks all the ships he commands.

Tamminen (born 1966) is a master of very short prose – this miniature novel is a a huge undertaking in the context of his work as a whole – and at Books from Finland we’re big fans. You can read more of his work here.

We join the story as Huurna, leaving behind him a failed romance in Viipuri, sets sail for Archangel, on the far north coast of Russia.

![]()

An excerpt from Meriromaani. Eräitä valoisia hetkiä merikapteeni Vilhelm Huurnan synkässä elämässä (‘A maritime novel. A few bright moments in Captain Vilhelm Huurna’s sombre life’, Otava, 2015)

The sun shone on the Arctic Ocean night and day, and the voyage went amazingly well, as did all the tasks and jobs that Huurna particularly feared beforehand.

Ships lay in Archangel harbour like objects on a collector’s shelf. They were waiting for timber cargo from the local sawmills where work was at a standstill because the mills lacked the machines and machine parts that they were now bringing them. When their cargo had been unloaded and the machines installed, timber began arriving from the sawmills. They found themselves at the end of the queue, and after the other ships had departed, one by one, they were still waiting in Archangel. That suited Huurna; in the first few days of his stay he had become acquainted with two English merchants and, through them, had received invitations to parties. He had stood in salons drinking toasts to the honour of this or that and made the acquaintance of some charming ladies into whose eyes he wished to gaze another time. He was quite moved by the whirl of this unexpected social life, and brightened at the thought that there was really nothing to complain about in his life apart from the fact that he happened still to be a bachelor. More…

Kullervo

31 March 1989 | Archives online, Drama, Fiction

An extract from the tragedy Kullervo (1864). Introduction by David Barrett

The plot of the Kullervo story as told in the Kalevala: Untamo defeats his brother Kalervo’s army, and Kalervo’s son Kullervo is born a slave. Untamo sells him as a young child to llmarinen whose wife, the Daughter of Pohjola, makes the boy a shepherd and bakes him a loaf with a stone inside it. Kullervo takes his revenge by sending home a flock of wild animals, instead of cattle, who tear her to pieces. He flees, and discovers that his parents and two sisters are alive on the borders of Lapland. He finds them, but one of his sisters is lost. Life in the family home is unhappy: Kullervo fails in all the tasks his father sets him. On his way home one day he finds a girl in the forest whom he abducts in his sledge and seduces. It turns out the girl is his lost sister, who drowns herself when she learns that Kullervo is her brother. Kullervo sets out to revenge himself on Untamo; he kills and destroys. When he returns home, he finds the house empty and deserted, goes into the forest and falls on his sword.

ACT II, Scene 3

Kalervo’s cottage by Kalalampi Lake. It is night-time. Kimmo, seated by a fire of woodchips, is mending nets. More…

Money makes the world go round

31 August 2012 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Mr. Smith (WSOY, 2012). Introduction by Tuomas Juntunen

I have a confession to make.

I couldn’t have lived on my salary. Most people would solve this by taking out a loan, living on credit. I’ve never lived in debt. Instead I’ve had to make my modest capital grow by investing it – through the company, of course, because irrespective of their colour governments generally understand companies better than small investors. You have to make money somewhere other than the Social Security Office.

Work doesn’t make money; money makes money.

You have to let money do the work.

This is nothing short of a profound human tragedy: most people are forced to waste the majority of their lives, to use it in the service of complete strangers, for unknown purposes, doing something for money that they would never do if they didn’t have to. The most shocking thing is that people actively seek out this state of affairs, strive towards it; it is a goal towards which society lends us its full support, no less.

Such wage slavery is called ‘work’. More…

Mole’s hole

31 March 1992 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Pikku karhun talviunet (‘The little bear’s winter dreams’, published posthumously in 1974, edited by Mirkka Rekola), prose fragments and fairy-tales. (See commentary by Soila Lehtonen)

Vauveli-Vau had grown up. She went round to Mole Hill and went into Mole’s Hole, so she could work in peace. As there are a lot of Mole’s Holes in the earth, no one had any idea where Vauveli-Vau had gone. They weren’t all that keen to know, as there’s always rather a lot to do in Mole’s Hole: pine cones and branches to be collected, trips to be made to the spring in the forest, an eye kept on Dottypot in the fire-embers, and at night you have to get up to see which bird it is that’s singing in the old rotten tree. But still more laboursome are the thick books in foreign languages and the pile of blank paper.

Quite a few days and nights had gone by before Vauveli-Vau was used to being in Mole’s Hole. During those days a lot of remarkable things occurred. A slug flourished his horns and muttered: ‘Who on earth would want to lie about in his cottage in fine weather like this?’ More…

Shards from the empire

5 February 2010 | Fiction, Prose

‘Imperiets skärvor’, ‘Shards from the empire’, is from the collection of short stories, Lindanserskan (‘The tightrope-walker’, Söderströms, 2009; Finnish translation Nuorallatanssija, Gummerus, 2009)

Gustav’s greatest passion is for genealogy. He dedicates his free time to sketching coats of arms; masses of colourful, noble crests.

Gustav asked me to do a translation. I sat for ten days trying to decipher a couple of pages from a Russian archive dating from the 1830s. Sentences like, With this letter, we hereby give notice of our gracious decision.‘

The intricate handwriting belonged to some collegiate registrar or other. Perhaps Gogol’s Khlestakov. More…

Do you remember the yellow house?

14 February 2011 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Enkelten kirja (‘The book of angels’, Tammi, 2010)

[Tallinn, summer] The past will not go away

and the present is insurmountable. Summer vacation has begun, the newspaper hasn’t come; it doesn’t get delivered here anyway. Can you remember the Isabelline yellow house? Remember the alley with the name that means hurry? Surely you remember the home with all the maps on the shelves, the important papers and the brass objects bought from nearby antique dealers? Also the rugs from North Africa and the obligatory cedar camel figurines on the windowsill. And so many glasses and plates and empty lighters in a cardboard box on the shelf on the left hand side of the kitchen.

Tallinn, June 7th. The floors creak. One step has split in half; some of the lights have burned out. This is a lovely home. A small window upstairs is ajar to the courtyard. Tuomas had latched it behind the Virginia creepers. The fountain in the courtyard is dry. On cold nights the smoke from the fireplace grows like a statue for the crows until it wraps around over the layered rooftops like a snake eating its tail. Russian men are repairing the attic of the house across the street for wealthy people to live in; they laugh in front of the window and smoke. Tuomas waves at them, and they wave back. The courtyard is creepy when it’s empty. Soon the neighbours would go about their day and quietly close their doors behind them, and two nearby churches would divide the hours into quarters, Russians and their gossip would make their way to the Alexander Nevski Cathedral, and the Estonians and their gossip would go to their own churches where a wise and peculiar, almost human scent would rise from between the headstones. Tuomas wouldn’t smell it, Aino would and would move to stand beneath the the center tower. More…