Search results for "2010/10/mikko-rimminen-nenapaiva-nose-day"

The Onlookers

30 September 1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Naisten vuonna (‘In women’s year’, 1975). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

The two elks came out on to the road through a gap between timber sheds. They began to cross the road, and the larger one was very nearly run into by a car. Cars stopped and horns tooted, till the elks turned and made off towards the harbour. Several cars swung round and drove along the cinder track in pursuit of the animals.

The elks headed across the rubble towards the power station; after circling some stacks of railway sleepers, they ended up on the flank of a coalheap sixty feet high. The cars pulled up and their occupants poured out, shouting that the elks wouldn’t go that way, it was a dead end. The elder of the two elks had indeed sensed this, and they moved off to the right, skirting the coal-heap and emerging among the timber-stacks. By this time the first cyclists and pedestrians had arrived on the scene.

“They’ll break their legs,” said a pedestrian to a motorist. “There’s all kinds of junk lying about.” More…

Patsy, the artist of the lumber camps

31 December 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Atomintutkija ja muita juttuja (1950). Introduction by Aarne Kinnunen

Deep in the wilds, where the only sound is the sad, primeval sighing of the forest, it is easy to succumb to a mood of boredom and melancholy. It may sometimes occur to you that in such a place you are wasting your life. Real life goes on elsewhere, in places with more people, more signs of human activity, more light, more gaiety…

You fell a tree, severing a string of that mighty instrument, the forest. You saw it into logs, you strip off the bark: it all seems dull and pointless. Sometimes the rain decides to go on for days: the trees have streaming colds, droplets hang from every needle-tip. You make for the shelter of a lumber camp. But the low-roofed rest-hut, deep in the forest, looks a dreary place, the well-known faces are so dull, the talk so futile. You feel you know in advance what each man is going to say. And the food, too, is just the same as usual, the same old rubbishy mush. The sight of the pot, with its blackened sides, gives no pleasure: you know all too well what is in it. And those grubby playing-cards, how disgusting! The mere sight of them is enough to make you feel defiled… More…

The honey of the bee

30 June 2005 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from the collection Mitä sähkö on (‘What electricity is’ WSOY, 2004). Introduction by Jarmo Papinniemi

Five days before I was born my grandfather reached sixty-six. He’d always been old. The first image I have of him gleams like a knife on sunny spring-time snow: he was pulling me on my sledge over hard frost under a bright glaring-blue sky. In the Winter War a squadron of bombers had flown through the same blue sky on their way to Vaasa; the boys leapt into the ditches for cover, as if the enemy planes could be bothered to waste their bombs on a couple of kids. Be bothered? Wrong: kids were always the most important targets.

Now it’s summer, August, and I’m sitting on the grassy, mossy face of the earth, which is slowly warming in a sun that’s accumulated a leaden shadiness. I’m sitting on my grandfather’s land. It’s the time when the drying machines buzz. Even with eyes shut, you can sense the corn dust glittering in the sun. Even with eyes shut, you can take in the smell of the barn’s old wood, the sticky fragrance of the blackcurrants barrelled on its floor, the tins of coffee and the china dishes on the shelves, and the empty grain bins; there’s the cupboard Kalle made, with its board sides and veneered door, and the dust-covered trunk that was going to accompany my grandfather to another continent. The ticket was already hooked, but Grandfather’s world remained here for good. When Easter comes we’ll gather the useless junk out into the yard and burn it; Grandfather’s travel chest will rise skywards. Grandfather stands in the barn entrance, leaning on the doorpost. He’s dead. Over all lies a heavy overbearing sun. Beyond the field the river’s flowing silently in its deep channel. At night time its dark and warm. More…

Poems

30 June 1979 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction, poetry

Kirsi Kunnas. Photo: Jyrki Luukkonen

Poems from Tiitiäisen satupuu (‘The Tittytumpkin’s fairy tree’, 1956)

The old water rat

There’s a shiver of a reed,

a rustle in the grass,

a slop-slopping through the mud:

Who’s that puffing past?

Who’s that peeping there?

A whiskery head

and a muddy tread.

It’s Old Mattie

Water Rattie.

Squeezing water from his eyes,

trickling from his sneezing nose,

freezing and sneezing.

Then: Oh dear Misery!

A-snee, a-snee, a-snizzery! More…

Mothers and sons

30 March 2008 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Helvi Hämäläinen’s novel Raakileet (‘Unripe’, 1950. WSOY, 2007)

In front of the house grew a large old elm and a maple. The crown of the elm had been destroyed in the bombing and there was a large split in the trunk, revealing the grey, rotting wood. But every spring strong, verdant foliage sprouted from the thick trunk and branches; the tree lived its own powerful life. Its roots penetrated under the cement of the grey pavement and found rich soil; they wound their way under the pavement like strong, dark brown forearms. Cars rumbled over them, people walked, children played. On the cement of the pavement the brightly coloured litter of sweet papers, cigarette stubs and apple cores played; in the gutter or even in the street a pale rubber prophylactic might flourish, thrown from some window or dropped by some careless passer-by.

The sky arched blue over the six-and seven-storey buildings; in the evenings a glimmer could be seen at its edges, the reflection of the lights of the city. A group of large stone buildings, streets filled with vehicles, a small area filled with four hundred thousand people, an area in which they were born, died, owned something, earned their daily bread: the city – it lived, breathed….

Six springs had passed since the war…. Ilmari’s eyes gleamed yellow as a snake’s back, he took a dance step or two and bent over Kauko, pretending to stab him with a knife. More…

Perfect thing

31 December 2000 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Ennen päivänlaskua ei voi (‘Not before sundown’, Tammi, 2000). Interview and introduction by Soila Lehtonen

A youngster is asleep on the asphalt in the backyard, near the dustbins. In the dark I can only make out a black shape among the shadows.

I creep closer and reach out my hand. The figure clearly hears me coming, weakly raises its head from the crouching position for a moment, opens its eyes, and I can finally make out what it is.

It’s the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.

I know straight away that I want it. More…

A day in the life

30 September 1996 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Drakarna över Helsingfors (‘Kites over Helsingfors’, Söderströms, 1996). Introduction by Jyrki Kiiskinen

It is December 1970, it is Friday afternoon and Helsingfors is shrouded in a damp, leaden-grey fog when Jacke Pettersson, trainee electrician at Mid-Nyland Vocational College, signs a receipt for his driving licence at Vallgård Police Station.

At home in the flat in Svenska Gården in Munkshöjden: the very next evening Jacke sneaks his hand down into his father’s, typesetter K-G. Pettersson’s, overcoat pocket. It is getting on for 9 o’clock and KG is sitting deeply submerged in his favourite armchair, staring concentratedly at the premiere of a new show.

Six out of forty

make it every week

sings a bright girl’s voice.

Then: the Official Supervisors and their solemn ‘Good evening’. And then: the blonde girl in her mini-dress and high boots, the glass holder with its plastic balls, the plastic balls with numbers on. More…

Punishment and delight

31 December 1995 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Pimeästä maasta (‘Out of the Land of Darkness’, Kirjayhtymä, 1995). Interview by Jukka Petäjä

‘A being far more powerful and wiser than ourselves made the mould at the beginning of time and set it up for us as a model in order that we might shape ourselves correctly,’ the teachers said. ‘The Prime Mover’s form, actions and thoughts we are unable to understand. The Prime Mover gave us the mould in order that we should not remain formless. To this extent it has made itself known to us, although we do not deserve anything from it. It did not make the mould of bog-iron, which would soon have rusted in the cellar, but of a much better material of which we know nothing, and need to know nothing. Our duty is to aspire to fill the perfect mould given to us perfectly. Most of us will never be able to do so, for we are worthless, formless, unclean messes who deserve, many times over, all the pain of fitting the mould.’

Ulthyraja Tharabereghist did not dare ask anything, but there was something she would have liked to know. How the Prime Mover had made the mould, at least, and where it had found the materials, and what the Mover had gone on to do and where it had gone when the mould was ready and in the possession of the villagers. Even illicit thoughts were said to damage one’s shape: to be visible in it, if one knew how to look, and, of course, to be felt in the pains of fitting the mould… More…

The rocket

30 September 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Raketen (‘The rocket’), a novella from the collection Den segrande Eros (‘Eros triumphant’), 1912. Introduction by George C. Schoolfield

The sun shone straight in through the veranda’s little windows that made the whole ‘villa’ resemble a hothouse. With a sigh, Elsa let the morning paper fall to the floor; she had gotten halfway through the classified ads: ‘Three lads wish to correspond with likeminded lasses.’ ‘If Mr Söders-m does not fetch his effects, left as bond for unpaid rent, within a week, they will be regarded as our property, and his name will be published in toto.’ Now she could stand no more. The air seemed to come from a bakeoven. Listlessly, she watched two flies as they flicked the ceiling paper in their humming dance of love. It seemed as though knives were being thrust into the back of her head; that was the way her sick headaches began. A long walk might stop it, she knew, but she felt too tired.

At last, she was able to make herself get up and open the door for some fresh air. But with the air she got a powerful smell of roasting pork from the baker’s villa; the yells of the children playing cops and robbers up on the rock were doubled in force. A nasty stabbing sensation began in Elsa ears. And so she decided to take a walk after all, but only to the steamboat jetty. More…

Teemu Kupiainen & Stefan Bremer

Music on the go

3 March 2010 | Extracts, Non-fiction

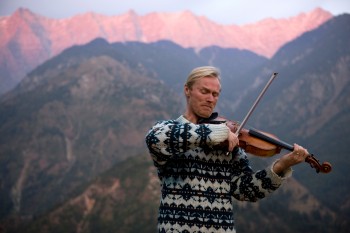

A little night music: Teemu Kupiainen playing in Baddi, India, as the sun sets. Photo: Stefan Bremer (2009)

It was viola player Teemu Kupiainen‘s desire to play Bach on the streets that took him to Dharamsala, Paris, Chengdu, Tetouan and Lourdes. Bach makes him feel he is in the right place at the right time – and playing Bach can be appreciated equally by educated westerners, goatherds, monkeys and street children, he claims. In these extracts from his book Viulun-soittaja kadulla (‘Fiddler on the route’, Teos, 2010; photographs by Stefan Bremer) he describes his trip to northern India in 2004.

In 2002 I was awarded a state artist’s grant lasting two years. My plan was to perform Bach’s music on the streets in a variety of different cultural settings. My grant awoke amusement in musical circles around the world: ‘So, you really do have the Ministry of Silly Walks in Finland?’ a lot of people asked me, in reference to Monty Python. More…

Poems

30 June 1985 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Introduction by Bo Carpelan

A flower beckons there, a secent beckons there, enticing my eye. A hope glimmers there. I will climb to the rock of the sky, I will sink in the wave: a wave-trough. I am singing tone, and the day smiles in riddles.

*

Like a sluice of the hurtling rivers I race in the sun: to capture my heart; to seize hold of that light in an inkling: sun, iridescence. In day and intoxication I wander. I am in that strength: the white, the white that smiles.

*

To my air you have come: a trembling, a vision! I know neither you nor your name. All is what it was. But you draw near: a daybreak, a soaring circle, your name.

Dead calm

31 December 2007 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel En lycklig liten ö (‘A happy little island’, Söderströms, 2007)

In the beginning the computer screen was without form, and void, and the scribe’s fingers rested on the keyboard.

The scribe bit his lower lip. His gaze travelled like a fly from the workroom’s crowded bookshelves to the rocking chair in front of the window and the coloured prints of birds on the walls. He went out into the kitchen and drank some water. Then he sat down in front of the computer again.

To create from nothing a fictitious world assisted only by the tools language places at our disposal, surely that must be a great and exacting undertaking!

The scribe hesitated and racked his brains for a long time before finally typing the first word: ‘sky’. Then after long thought he typed another word: ‘sea’. More…

Living with Her Ladyship

31 December 2003 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the memoir of a Helsinki childhood, Från Twenty Gold till Kent (‘From Twenty Gold to Kent’, Schildts, 2003). Introduction by Pia Ingström

My hair was dark and stuck up from my skull like little nails. My face was furrowed with red, my throat was wrinkled and I didn’t even have a pretty navel. This was because Daddy had to knot my umbilical cord himself while the obstetrician was busy on the ground floor with an appendix.

‘She looks like a forty-year-old errand-boy from the newspaper’s office: Daddy announced.

Mummy said she hoped I would soon change and have a long neck.

At Apollogatan street we took the lift up to the third floor where my sisters were waiting with the new nanny. They had no chance to welcome me with singing as they’d planned because both Renata and Catherine had colds. Nobody was going to be allowed to breathe anywhere near me, Mummy and Nanny were entirely agreed on that. More…

A spot of transmigration

13 January 2011 | Fiction, Prose

A short story, ‘Sielunvaellusta’, from the collection Rasvamaksa (‘Fatty liver’, WSOY, 1973)

‘Where will you be spending Eternity?’ a roadside poster demanded as Leevi Sytky sped by in his car.

‘Hadn’t really thought about it,’ Leevi muttered , as if in reply, and lit a cigarette.

But at the next level crossing, a kilometre or so further on, he was run down by a train, whose approach he had failed to notice. His attention had been distracted by the sight of a young woman who was picking black currants by the side of the track, and who happened to be bending forward in his direction. Intent on obtaining a better view of her ample bosom by peering over the top of her blouse, Leevi neglected to look both ways, and death ensued. Damned annoying, to say the least.

In due course he secured an interview with God, who turned out to be a biggish chap, about a hundred metres tall, wearing thigh-boots and sitting behind a large desk.

‘Well, and how’s Leevi Sytky getting along?’ God asked, lighting his pipe.

‘Mustn’t grumble,’ said Leevi politely.

‘And how are you thinking of spending Eternity?’ God inquired, sucking at his pipe and puffing out his cheeks. More…