Search results for "2011/04/2010/05/song-without-words"

True or false?

An extract from the novel Toiset kengät (‘The other shoes’, Otava, 2007). Interview by Soila Lehtonen

‘What is Little Red Riding Hood’s basket like? And what is in it? You should conjure the basket up before you this very moment! If it will not come – that is, if the basket does not immediately give rise to images in your minds – let it be. Impressions or images should appear immediately, instinctively, without effort. So: Little Red Riding Hood’s basket. Who will start?’

Our psychology teacher, Sanni Karjanen, stood in the middle of the classroom between two rows of desks. Everyone knew she was a strict Laestadian. It was strange how much energy she devoted to the external, in other words clothes. God’s slightly unsuccessful creation, a plump figure with pockmarks, was only partially concealed by the large flower prints of her dresses, her complicatedly arranged scarves and collars. Her style was florid baroque and did not seem ideally suited to someone who had foresworn charm. Her hair was combed in the contemporary style, her thin hair backcombed into an eccentric mountain on top of her head and sprayed so that it could not be toppled even by the sinful wind that often blew from Toppila to Tuira. More…

The mistake

30 September 2008 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story (‘Erehdys’, 1956, last published in the collection Lukittu laatikko ja muita kertomuksia, ‘A locked box and other stories’, WSOY, 2003). Introduction by Markéta Hejkalová

My feet are smarter than my head. On an April night in Naples they carried me along the Via Roma past the royal palace and the giant illuminated dome of the church. The people of Naples walked up and down the immortal street like the cool of evening, looking at each other and at the brightly lit display windows. I had nothing against that, but at the comer of Via San Brigida my feet turned to the right. The snow-cold breath of my homeland radiated toward me from Saint Bridget Street.

When I had turned the corner I could see a restaurant window still lit, with its fruit baskets, dead fish and red lobsters. The most hurried diners had already finished their meals. I stepped into the long dining room of the restaurant, the sawdust on the floor stuck to my shoes, a frighteningly icy stare pierced me from behind the counter, but I gathered my courage and whispered bravely, ‘Buona sera, signora.’ More…

Nationalism in war and peace

3 May 2012 | Reviews

House of words: the Finnish Literature Society building in Helsinki. Architect Sebastian Gripenberg, 1890. Watercolour by an unknown Russian artist, 1890s

Kai Häggman

Sanojen talossa. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura 1890-luvulta talvisotaan

[In the house of words. The Finnish Literature Society from the 1890s to the Winter War]

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2012. 582 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-328-9

€54, hardback

The Finnish Literature Society has, throughout its history, played a multiplicity of roles: fiction publisher, research institute specialising in folklore studies, organiser of mass campaigns in support of national projects, literary gatekeeper, learned society, controller of language development.

The priorities of these areas of interest have changed from decade to decade, so Kai Häggman has taken on an exceptionally difficult subject to describe. He has, however, succeeded brilliantly in gathering the different threads together, using as as lowest common denominator the ideas of nationalism and nation whose role in global modernisation and European history have been studied, among others, by the British historians Ernest Gellner and Eric Hobsbawm. More…

Melba, Mallinen and me

30 June 1993 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Fallet Bruus (‘The Bruus case’, Söderströms, 1992; in Finnish, Tapaus Bruus, Otava), a collection of short stories

After the war Helsingfors began to grow in earnest.

Construction started in Mejlans [Meilahti] and Brunakärr [Ruskeasuo]. People who moved there wondered if all the stone in the country had been damaged by the bombing or if all the competent builders had been killed; if you hammered a nail into a wall you were liable to hammer it right into the back of your neighbor’s head and risk getting indicted for manslaughter.

Then the Olympic Village in Kottby [Käpylä] was built, and for a few weeks in the summer of 1952 this area of wood-frame houses became a legitimate part of the city that housed such luminaries as the long-legged hop-skip-and-jump champion Da Silva, the runner Emil Zatopek (with the heavily wobbling head), the huge heavyweight boxer Ed Saunders and the somewhat smaller heavyweight Ingemar Johansson who had to run for his life from Saunders. More…

Narcissus in winter

31 December 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

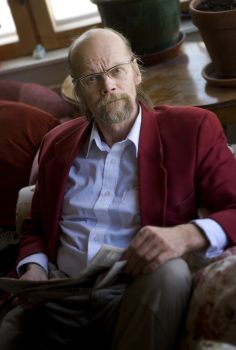

Risto Ahti. Kuva: Harri Hinkka

Poems from Narkissos talvella (‘Narcissus in winter’, 1982). Introduction by Pertti Lassila

Risto Ahti (born 1943) published his first work in 1975. His poetic expression finds form remarkably often in prose poems, and Narkissos talvella is made up exclusively of these. His poems transmute language into a mystical, surreal world, sometimes enigmatic and subjective in the extreme, and at its best strangely suggestive. It is as if Ahti’s world were in a state of constant change, subjected to a relentless process of demolition and rebuilding. The experience of the individual, generally his encounter with truth, is central to many of Ahti’s poems; the inner reality of a person manifests itself as more essential than the outward appearance. Ahti’s poems exhibit a fruitful contradiction: on the one hand, the accuracy with which he uses words and, on the other, the continual shape-changing and lack of definite boundaries of the world they describe. More…

Wolf-eye

30 June 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Käsky (‘Command’, WSOY, 2003). Introduction by Jarmo Papinniemi

Only once he had led the woman into the boat and sat down in the rowing seat did it occur to Aaro that it might have been advisable to tie the woman’s hands throughout the journey. He dismissed the thought, as it would have seemed ridiculous to ask the prisoner to climb back up on to the shore whilst he went off to find a rope.

It was a mistake.

After sitting up all night, being constantly on his guard was difficult. Sitting in silence did not help matters either, but they had very few things to talk about. More…

The miracle of the rose

30 June 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Naurava neitsyt (‘The laughing virgin’, WSOY, 1996). The narrator in this first novel by Irja Rane is an elderly headmaster and clergyman in 1930s Germany. In his letters to his son, Mr Klein contemplates the present state of the world, hardly recovered from the previous war, his own incapacity for true intimacy – and tells his son the story of the laughing virgin, a legend he saw come alive. Naurava neitsyt won the Finlandia Prize for Fiction in 1996

28 August

My dear boy,

I received your letter yesterday at dinner. Let me just say that I was delighted to see it! For as I went to table I was not in the conciliatory frame of mind that is suitable in sitting down to enjoy the gifts of God. I was still fretting when Mademoiselle put her head through the serving hatch and said:

‘There is a letter for you, sir.’

‘Have I not said that I must not be disturbed,’ I growled. I was surprised myself at the abruptness of my voice.

‘By your leave, it is from Berlin,’ said Mademoiselle. ‘Perhaps it is from the young gentleman.’

‘Bring it here,’ I said. More…

The prisoner and the prophet

30 June 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Timmermannen (‘The carpenter’, Söderströms, 1996). Introduction by Jyrki Kiiskinen

The greatest message

Reader, love is

a secret, waiting

for wind, not a choice

between loving or not.

As commandment, degraded

to demand, it will soon be

fanatic like a wound,

a form of hate. How

could a secret

become reality

without dying? Every

decree destroys its region. Made a law

goodness turns

into the protecting

skin, with which the good

touches everything. A demand

for understanding, that,

which we call wisdom,

makes of wisdom

an armour, a cold

father around us.

The real communication is

his life. Against evil stands

the tale of a face.

How could such a secret

become real

or die? More…

Breton without tears

31 March 1994 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Euroopan reuna (‘The edge of Europe’, Otava, 1982). Introduction by H. K. Riikonen

I am reading a book, it says pour l’homme latin ou grec, un forme correspond à un être; pour le Celte, tout est metamorphose, un même individu peut prendre des apparences diverses, so it says in the book. A strange claim, considering that the word metamorphosis is Greek, and that the best-known book about metamorphoses, Ovid’s Metamorphoseon libri XV was written in Latin. In the myths of all peoples, at least the ones whose oral poetry was recorded in time, such as the Greeks, Serbs, Slavs, Finns, or Aztecs, metamorphoses play a very important part, the Celts are not an exceptional tribe in this respect. The author must mean that the Celts still live in mythical time, the time of metamorphoses when the human being assumed shapes, was able to fly as a bird, swim as a fish, howl as a wolf, and to crown his career by rising up into the sky as a constellation. Brittany is part of the Armorica Joyce tells us about in Finnegans Wake, that book is incomprehensible if one does not know Ireland, and now I see that Brittany is the key to one of the book’s locked rooms. I thought I already had keys to all the rooms after Dublin, the Vatican, and Athens, but one door was and remained closed, the key is here now, in my hand, I can get into all the rooms in the book, and I am home even if I should happen to get lost. The room creates the person, she becomes another when she goes from one room to another, this is metamorphosis, and when she leaves the house she disappears, she no longer exists. The legend on the temple at Delphi, gnothi seauton, know thyself, has led Occidentals onto the false track that is now becoming a dead end, polytheistic religions correspond to the order of nature, but as soon as the human starts to imagine that she knows herself, as soon as the metamorphic era ends, monotheism is born, the human being creates god in her own image, and that is the source of all evil. Planted like traffic signs at the far end of this cul-de-sac stand the hitlers and brezhnevs and reagans and thatchers, new leaves are appearing on the trees, the sun is shining. Landet som icke är* är en paradox: landet blev befintligt därigenom att Edith Södergran sade att det icke är. On the sea sailed a silent ship*, as I tracked my shoeprints across the sand on the beach, it was like walking on a street made out of salty raw sugar, I felt desolate. The wind bent the grasses, the sun warmed the back of my sweater, of course the sun always has the last word, I thought, things should be as they are, this thought gave me peace of mind. I walked past the cows, two of them already chewing the cud, the others still grazing, they stood in a line and raised their heads, stood at attention, as it were, as I walked past. I was not entirely sure that I was heading in the right direction, but then I saw the boucherie and knew that there was a café nearby. Madame greeted me in a friendly fashion, brought me a calvados and a beer and sat down for a chat, wanted to know if I liked the countryside here. I said that things looked the same here as in Ireland, she said that was true, but she had never been to Ireland. I finished my drinks and paid, left, decided to walk along the beach. I saw gun emplacements and two bunkers. I crawled into a bunker. Inside, it was dark and damp. I looked through the embrasure at the sea. I thought of the boys who had been incarcerated here. They had been given a death sentence. I examined a rusty object, what was it, I looked at it more closely, it was an axle from a gun’s undercarriage. As I arrive in my home yard, I note that the lilacs are beginning to bloom. More…

Paris match

30 June 2011 | Articles, Non-fiction

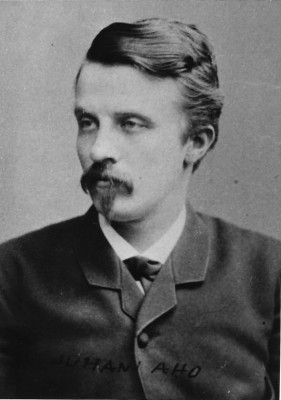

In 1889 the author and journalist Juhani Aho (1861–1921) went to Paris on a Finnish government writing bursary. In the cafés and in his apartment near Montmartre he began a novella, Yksin (‘Alone’), the showpiece for his study year. Jyrki Nummi introduces this classic text and takes a look at the international career of a writer from the far north

Juhani Aho. Photo: SKS/Literary archives

Yksin is the tale of a fashionable, no-longer-young ‘decadent’, alienated from his bourgeois circle, and with his aesthetic stances and social duties in crisis. He flees from his disappointments and heartbreaks to Paris, the foremost metropolis at the end of the 19th century, where solitude could be experienced in the modern manner – among crowds of people. Yksin is the first portrayal of modern city life in the newly emerging Finnish prose, unique in its time.

Aho’s story has parallels in the contemporary European literature: Karl-Joris Huysmans’s A Rebours (1884), Knut Hamsun’s Hunger (1890) and Oscar Wilde’s The Portrait of Dorian Gray (1890). More…

Nature boy

15 September 2011 | In the news

Seal signed: Saimaa ringed seal by Erik Bruun

The graphic artist Professor Erik Bruun has been awarded the Luonnotar / National Spirit of Nature Award for 2011.

The prize, established by the Puu kulttuurissa / Wood in Culture Association in 2001 and now worth € 12,000, is awarded bi-annually to Finnish professionals of any field of culture whose work has helped to make the public in Finland and abroad more aware of Finnish culture, heritage and environment.

Erik Bruun (born 1926) – who was the Art Editor of Books from Finland from 1976 to 1989 – is perhaps best known to the public for his numerous posters and advertisements, in particular his nature posters for the Finnish Association for Nature Conservation: the Saimaa ringed seal, the bear, eagles, owls, seagulls and other birds.

Bruun’s interest in nature photography, drawing, etching and lithography have long combined in his work for the Finnish wood processing industry as well as in his illustrative work for magazines and books and in designing postage stamps and banknotes.

A book on his life’s work, Sulka ja kynä. Erik Bruunin julisteita ja käyttögrafiikkaa (‘The quill and the pen. Posters and graphics by Erik Bruun’) by Ulla Aartomaa was published in 2007 (and reviewed in Books from Finland 3/2007). Take a look at his work on his home page.