Search results for "2011/04/2010/05/song-without-words"

Tellervo Krogerus: Sanottu. Tehty. Matti Kuusen elämä 1914–1998. [Said. Done. The life of Matti Kuusi, 1914–1998]

22 May 2014 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Sanottu. Tehty. Matti Kuusen elämä 1914–1998

Sanottu. Tehty. Matti Kuusen elämä 1914–1998

[Said. Done. The life of Matti Kuusi, 1914–1998]

Helsinki: Siltala , 2014. 856 pp., ill .

ISBN 978-952-234-194-5

€31.50, hardback

The folklorist Matti Kuusi vied for the status of the world’s leading researcher of proverbs with the Californian scholar Archer Taylor, his work extending from the shores of the Baltic Sea to Namibia’s Ovamboland. Proverbs revealed to him the deep structures of the human mind and showed that the nations of the world possessed a basis for mutual understanding. As a young man Kuusi read Spengler and predicted the destruction of the Western world. According to his ‘Kalevalan imperialism’, the Nordic region was to be the new world power. The war brought him to his senses: he understood that patriotism was mainly a matter of bland resilience. Professor Kuusi was a rigorous scholar, but also a provocative man of ideas who showed that pop music was today’s folk poetry. That idea received a mixed reception, but nowadays his department studies both rap music and ancient folk song. This biography by Tellervo Krogerus creates a rich portrait of a complex personality.

Translated by David McDuff

Writing silence

6 June 2013 | Fiction, poetry, Reviews

In contemporary poetry the ‘lyric I’ of previous decades often hides behind language; the poem’s speaker is not the poet him/herself, narrative is not the norm. The website of a Finnish family magazine in 2007 discussed this: ‘OMG, this thing called contemporary poetry – crap!’; ‘Who knows what kind of psychopharma the writer’s on!’; ‘No meanings, just words one after the other. Why can’t people write something sensible?’ But the writer – and the reader – of contemporary poetry deliberately ventures onto the boundaries of language, and art requires readers (listeners, viewers) to make the decision of what they consider ‘sensible’. Mervi Kantokorpi explores and interprets two new collections of poetry

I read two of this spring’s new collections of poetry one after the other: Kivirivit (‘Stone lines’, Otava 2013) by Harry Salmenniemi and Pysty hiljaisuus (‘Vertical silence’, Teos 2013) by Miia Toivio. The experience was perplexing.

These two works are completely different from one another as regards their individual poetics, and yet the similarities between the themes that arise from them was arresting. Both works seem to inhabit an internal world of sorrow and depression, a world where the function of poetry is to forge and show its readers a path out of the anxiety. In their silence – and even emptiness – both collections have two faces: one lit up, the other darkened by grief. More…

Piranesi

30 August 2013 | Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel För många länder sedan (‘Many lands ago’ Schildts & Söderströms, 2013; Finnish edition: Monta maata sitten; Otava, 2013). Introduction by Pia Ingström

‘I assume your father wanted you to become a doctor?’ asked Igor at the beginning of our life together. My parents did indeed want me to become a doctor. Not a pathologist, but a general practitioner. I became an art historian instead. There was a time when my area of research aroused curiosity in Igor.

‘Why Piranesi?’ he wondered.

‘As a child I devoured classic novels about pale, emaciated families living in a cellar,’ I explained jokingly. ‘I became interested in catacombs and vaults. That’s why I wanted to study the history of drawing.’

I’ve always had a fascination for underground spaces. I’m drawn to them like a homing missile. This interest of mine must have genetic roots. My mother was born in a bomb shelter during the first German air raid over Leningrad. More…

Living with a genius

23 June 2015 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s painting Symposium (1894). From left: Akseli Gallen-Kallela, the composer Oskar Merikanto, the conductor Robert Kajanus and Jean Sibelius. Aino Sibelius was not pleased with this depiction of her husband depicted during a drinking session with his buddies

It is 150 years since the birth of Finland’s ‘national’ composer, Jean Sibelius. Much has been written about his life; Jenni Kirves’s new book casts light on his wife, Aino (1871–1969), and through her on the composer’s emotional and family life.

Aino, Kirves remarks in her introduction, has often been viewed as an almost saintly muse who sacrificed her life for her husband. But she was flesh and blood, and the book charts the difficulties of life with her brilliant husband from the very beginning – his unfaithfulness during their engagement, how to deal with a sexually transmitted infection he had contracted, his alcohol problem, the death of a child. It was Aino’s choice, time and again, to stand by her man; she felt it was her privilege to support her husband in his work in every possible way. ‘For me it is as if we two are not alone in our union,’ she wrote, far-sightedly, as a young bride. ‘There is also an equally rightful third: music.’

Aino’s own family, the Järnefelts, were a considerable cultural force in Finland, supporters of Finnish-language education and the growing independence movement. Her brothers included the writer Arvid Järnefelt, the artist Erik Järnefelt and the composer Armas Järnefelt. It was Armas who introduced her to his friend Jean Sibelius.

Aino bore Sibelius – known in family circles as Janne – six daughters, and offered her husband her unfailing support through 65 years of married life. ‘I must have you,’ Sibelius wrote, ‘in order for my innermost being to be complete; without you I am nothing… For this reason you are as much an artist as I am – if not more.’

As an old lady, Aino remarked of her own life that it had been ‘like a long, sunny day.’

![]()

Aino Sibelius, 1891. Photo: National Board of Antiquities – Musketti.

An excerpt from Aino Sibelius: Ihmeellinen olento (‘Aino Sibelius: wondrous creature’, Johnny Kniga, 2015). We join the young couple in 1892 as they prepare for their long-awaited wedding.

At last, the wedding!

In the spring of 1892 the wedding really began to seem possible, as Janne’s symphonic poem Kullervo was very favourably received and Janne finally began to believe that he could support Aino. His financial situation was still, however, far from brilliant, and there were only two weeks to the wedding, as Janne wrote on 27 May 1892: ‘All the same, we must really be very careful about money. You will keep the cashbox and we will decide on everything together.’ The wedding grew closer and three days later Janne wrote triumphantly:

Do you understand, Aino, that we shall be man and wife in 1 ½ weeks – that we shall be able to kiss each other however we like and wherever we like (!) – and live together and have a household together – eat and make coffee together – it’s just so lovely.

A couple of weeks before the wedding, however, Janne wrote to Aino about some wishes for Aino in the future:

A skill with which a married artist can be protected from regressing is that the ‘wife’ understands to make him as little as possible into a model citizen. The man must not be allowed to be a paterfamilias with a pipe in his mouth, drowsy and docile; he must continually seek as many impressions as before, that’s clear, isn’t it? The kind of marriage whose main goal is the bringing of children into the world is repugnant to me – there are most certainly other things to do for those who work in the arts. More…

A greater solitude

30 December 2004 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Runoilijan talossa (‘In the house of the poet’, Tammi, 2004)

Images of love

The double door to the patio is tightly swollen into the framework, so tight I’m chary of using force to prize it open. The windows might break. The lower part remains stuck, as if screwed to a carpenter’s bench, while the upper part gapes – leans out as if longing to liberate itself from its lintel. That’s an image of love: one part longs to be free, the other part holds on fast. I get a toolbox from the cleaning cupboard and try to hammer a chisel into the space between the bottom edge and the threshold. I succeed, but the chisel marks the door, defacing it. That’s an image of love too. More…

Punishment and delight

31 December 1995 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Pimeästä maasta (‘Out of the Land of Darkness’, Kirjayhtymä, 1995). Interview by Jukka Petäjä

‘A being far more powerful and wiser than ourselves made the mould at the beginning of time and set it up for us as a model in order that we might shape ourselves correctly,’ the teachers said. ‘The Prime Mover’s form, actions and thoughts we are unable to understand. The Prime Mover gave us the mould in order that we should not remain formless. To this extent it has made itself known to us, although we do not deserve anything from it. It did not make the mould of bog-iron, which would soon have rusted in the cellar, but of a much better material of which we know nothing, and need to know nothing. Our duty is to aspire to fill the perfect mould given to us perfectly. Most of us will never be able to do so, for we are worthless, formless, unclean messes who deserve, many times over, all the pain of fitting the mould.’

Ulthyraja Tharabereghist did not dare ask anything, but there was something she would have liked to know. How the Prime Mover had made the mould, at least, and where it had found the materials, and what the Mover had gone on to do and where it had gone when the mould was ready and in the possession of the villagers. Even illicit thoughts were said to damage one’s shape: to be visible in it, if one knew how to look, and, of course, to be felt in the pains of fitting the mould… More…

Writers meet again in Lahti

14 May 2009 | In the news

In other words: LIWRE at Messilä Manor

The Lahti International Writers’ Reunion (LIWRE; www.liwre.fi) will be held this year between 14 and 16 June.

In the politically and culturally active 1960s, marked by the confrontation between East and West, an idea was born to found an international, bi-annual rendezvous where writers from all over the world could freely engage in discussions on various themes.

Breadcrumbs and elephants

27 March 2014 | Essays, On writing and not writing

In this series, Finnish authors ponder the pros and cons of their profession. Alexandra Salmela operates in two languages, her native Slovakian and Finnish, which has become her literary language. Adventure and torture alternate as she attempts to shape reality into writing

I had started to write before I knew how. With fat wax crayons, in big stick-letters, I scratched my stories in old diaries. There were lots of pictures. From the very beginning, I wrote both poetry and prose. At 11 I didn’t finish my great sea-adventure novel, but at 12 I was already writing my memoirs. They, too, somehow remained unfinished.

Writing is… I wanted to write fun, but in the end I’m not quite sure about that. Writing is adventure and liberation and terribly hard work. Torture of the imagination and the pale copying of real events. Reading is a way to escape reality and at the same time a route to the sources of reality. By writing, you can shape reality in your own image: it’s your own character fault if the result is ugly and depressing.

If I were to write a pink world, it would be so sugary that it would make everyone sick, me and other people. More…

Letters from Tove

6 October 2014 | Extracts, Non-fiction

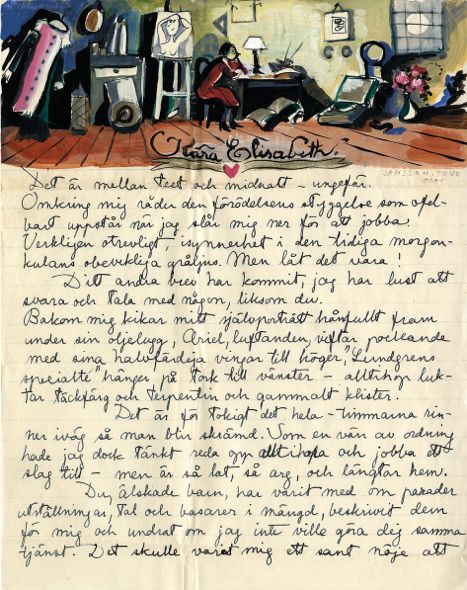

Early days: Tove Jansson went to Stockholm to study art when she was just 16. A letter to her friend Elisabeth Wolff, from November 1932

Artist and author Tove Jansson (1914–2001) is known abroad for her Moomin books for children and fiction for adults. A large selection of her letters – to family, friends and lovers – was published for the first time in September. In these extracts she writes to her best friend Eva Konikoff who moved to the US in 1941, to her lover, Atos Wirtanen, journalist and politician, and to her life companion of 45 years, artist Tuulikki Pietilä.

Brev från Tove Jansson (selected and commented by Boel Westin and Helen Svensson; Schildts & Söderströms, 2014; illustrations from the book) introduced by Pia Ingström

7.10.44. H:fors. [Helsinki]

exp. Tove Jansson. Ulrikaborgg. A Tornet. Helsingfors. Finland. Written in swedish.

to: Miss Eva Konikoff. Mr. Saletan. 70 Fifty Aveny. New York City. U.S.A.

Dearest Eva!

Now I can’t help writing to you again – the war [Finnish Continuation War, from 1941 to 19 September 1944] is over, and perhaps gradually it will be possible to send letters to America. Next year, maybe. But this letter will have to wait until then – even so, it will show that I was thinking of you. Curiously enough, Konikova, all these years you have been more alive for me than any of my other friends. I have talked to you, often. And your smiling Polyfoto has cheered me up and comforted me and has also taken part in the fortunate and wonderful things that have happened. I remembered your warmth, your vitality and your friendship and felt happy! At first I wrote frequently, every week – but after about a year most of it was returned to me. I wrote more after that, but the letters were often so gloomy that I didn’t feel like saving them. Now there are so absurdly many things I have to talk to you about that I don’t know where to begin. Koni, if only I’d had you here in my grand new studio and could have hugged you. After these recent years there is no human being I have longed for more than you. More…

Northern exposure

3 September 2005 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Valon reunalla (‘At the edge of light’, Teos, 2005). Introduction by Kristina Carlson

Kari

The village despised all those who left. They hated us too, though we were still only planning our final escape.

We used to escape the village. We would hide from its gaze in the forest or the cemetery where the gravestones were so close together that there was no room for the trees to grow. We knew why the freight train brought the village so many dead and so few living. It was the village’s fault. It had a wicked soul. The grown-ups didn’t know it. We knew it, but no one asked us. Death was within us; it was alive. Asking would have been too dangerous….

On the backs of the headstones we carved our own marks with the end of a knife. We blew out the candles laid at the graves of suicide victims. We worshipped them in the dark and no new candles were ever brought to their graves. The parents of those who died so young drove south. They were looking for stations with real waiting rooms and staff that made announcements. They sat on the hard benches waiting, waiting for the trains to come, at the right time; hoping the years wouldn’t wreak havoc after all, hoping they’d roll slowly back along the tracks, to brighten as they approached the village, giving life once again to their children. And everything could start over. More…