Search results for "2011/04/2010/05/song-without-words"

One more time

31 December 1999 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Kun elän (‘As I live’, Tammi, 1999). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

XI

Here is a treetop

with three

thousand branches,

three thousand

names, whose

syllables no one

knows, three

thousand minds,

one murmur

traversed by a

breath, a sentence,

I’m afraid to say

anything,

a million leaves

sough, speechless,

a thousand dark

branching roots,

names in the soil,

a million words

in humus heaven

a thousand sprouts

bloom yet are lifeless,

dead heroes,

pointless tales,

three million

wrinkles. faces

obscured

by branches,

in the brain’s roots

a new person’s thought

is born and

hums through branches,

roots,

the smoke disappears

through the branches,

the smoke disappears.

XVIII

He saw faces behind the glass,

heard himself breathe.

With his fingertips, he brushed the glass surface

but it was not the same as skin.

Slowly, he arranged what he saw,

that blurry motion, but it did not work

as an architecture, the kind

a living city is perennially building.

He opened up to a gaze, froze,

lost the game altogether.

Then the scythe disappeared. He opened

a window onto the street, heard

leaves rustle as if waking up

to life, one more time.

Intermission

But I did not sing,

I chased her away,

flushed the toilet, paced

circles in the living room

like a moth that looks for

a place to land

or a solution that does not exist

to a problem that probably

does not exist either,

just a wall full of

leather-backed books

and seats among which

the moth chooses one, a

commodified insomnia

a landscape someone

invented once: palaces,

persons, tensions,

systems and maps

constructed by language insects

on top oft he void,

in the air, an imago mundi

never seen before

never before heard-of

utopias, illnesses

people prefer to endure

rather than

giving up, once they have

forgotten the war’s causes

or the cornerstone of their learning

ground up to gravel

long ago, they still love

the country they have

destroyed, for love

is stronger than

its object, and who

needs it, the group

eats reason and everything learned,

it turns us into beasts,

the congregation executes

its christ, the state

its sages, but the sleepless

animal keeps wrestling

in the mud with its inner

hero, the beast; yearns, spits,

rages and grieves, looks for

reconciliation, tries

to mediate and interpret

between invisible enemies

to whom only sleep and murmur

can lend a shape, until the image

finally shatters

into sentences, steps

into line between covers,

on the shelf: in the closed pages

simmers yet another delirium

no one has ever seen before.

Four o’clock

Don’t know why I burst out laughing

in bed, but someone instantly answered

as if by rote, as if

comprehending eternity,

laughing without malice, life

and soul of the party, cruel

as a certain hero

who was asked to hold up

the roof while they were still making

speeches in the hall, while the fool

scratched his belly, raised his cup

to the host. while a woman

raised her skirt, the whole forest laughed

and every demon claw

inscribed history. from which

the laughter freed him.

All of a sudden the clock struck four,

but I heard only my heartbeat,

the rush of systole and diastole,

tides of a muddy delta,

the sleepless whimper

of birth and death, the streams of cellular fluids,

the pulsing of stars, the animal’s paws

as it padded along the runner,

all in step; not long now until the wolfs hour,

nothing stirred on the plains, I felt

a thundercloud push down on my forehead,

and the wind died, the grass

stopped rustling, sugar coagulated, and then

lightning stopped my heart with one blow,

in one rapid motion my hand

tore off the pillow case, my body

sat up in bed, my mouth shouted,

the primal animal, evolution howled.

Upright. he stood in front of me,

in the rearview mirror the car came closer

struck me again and again from behind

with a huge iron fist, made words burst

from my mouth, the car rose into the air: a plane,

a pegasus galloping straight at the pillar,

now muteness, the windshield

cracked, flew out in one piece

to rest on the hood

in the rearview mirror the car

came closer again, I saw how I flew

into the foliage, in my mind

two separate memories:

thus memory shatters time, and so

one can look at the past as true,

barely, barely endure it: she

bent over me, said something.

At the wake, lips moved. behind

the glass stood a fair boy

whom I knew, even though

he had already grown up to be a man.

Translated by Anselm Hollo

A fifth season

30 December 2000 | Fiction, poetry

Poems from Elävän mieli (‘A mind alive’, WSOY, 1999). Introduction by Lauri Otonkoski

In sparser gusts of wind

metaphors sough through the mind,

spinning as on the much-frequented

boulevards of a great park.

Even one’s most private thoughts are as common

as public transport, what a relief,

as shared as our anatomies and our bacteria,

for there is only one thread in the skein of the Norns

and the same fabric is always being woven

from the whims of fate: is that not a relief?

Treacherous individuality suffices only

for a fingerprint.

Metaphors always the same,

but constantly born anew

like a mind alive. More…

Money makes the world go round

31 August 2012 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Mr. Smith (WSOY, 2012). Introduction by Tuomas Juntunen

I have a confession to make.

I couldn’t have lived on my salary. Most people would solve this by taking out a loan, living on credit. I’ve never lived in debt. Instead I’ve had to make my modest capital grow by investing it – through the company, of course, because irrespective of their colour governments generally understand companies better than small investors. You have to make money somewhere other than the Social Security Office.

Work doesn’t make money; money makes money.

You have to let money do the work.

This is nothing short of a profound human tragedy: most people are forced to waste the majority of their lives, to use it in the service of complete strangers, for unknown purposes, doing something for money that they would never do if they didn’t have to. The most shocking thing is that people actively seek out this state of affairs, strive towards it; it is a goal towards which society lends us its full support, no less.

Such wage slavery is called ‘work’. More…

Writers’ talk

13 May 2011 | In the news

Under the midday sun: participants of the Writers' Reunion in 2005

Next month sees a new International Writers’ Reunion at Messilä Manor in the city of Lahti in central Finland. The first such meeting was organised in 1963.

Since then, more than a thousand writers, translators, journalists, critics and other book people, Finnish and foreign, have met for a few days every other year just before Midsummer to discuss various topics.

And the nights are light, and long, and the talking goes on.

This time the theme is ‘The writer beyond words’: how will the writer meet the limits of language and narration? (More on the topic in our article Beyond words.) The meeting takes place between 19 and 21 June.

So far about twenty writers, from Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Lithuania, Norway, Russia, Slovenia, Sweden and Udmurtia, are expected to arrive, as are some 20 Finnish participants. All debates and poetry evenings are open to the general public free of charge.

Gorgonoids

31 March 1993 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Matemaattisia olioita tai jaettuja unia (‘Mathematical creatures, or shared dreams’, WSOY, 1992). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

The egg of the gorgonoid is, of course, not smooth. Unlike a hen’s egg, its surface texture is noticeably uneven. Under its reddish, leather skin bulge what look like thick cords, distantly reminiscent of fingers. Flexible, multiply jointed fingers, entwined – or, rather, squeezed into a fist.

But what can those ‘fingers’ be?

None other than embryo of the gorgonoid itself.

For the gorgonoid is made up of two ‘cables’. One forms itself into a ring; the other wraps round it in a spiral, as if combining with itself. Young gorgonoids that have just broken out of their shells are pale and striped with red. Their colouring is like the peppermint candies you can buy at any city kiosk. More…

Writing and power

15 October 2009 | This 'n' that

Speaking in the cold: the Chairperson of the Lahti Writers' Union, Jarmo Papinniemi (left), and the Bosnian writer Igor Štiks (right) listen to Riina Katajavuori's presentation

The theme of the biannual International Writers’ Reunion (LIWRE) which took place in Lahti, southern Finland, in June for the 24th time, was ‘In other words’.

The theme inspired the participants (54 in total, foreign and Finnish) to talk, among other things, about the power of the written word in strictly controlled regimes, about fiction that retells human history, about the difference between the language of men and women, about languages that have been considered – by those who rule, naturally – ‘better’ than other languages. Eleven presentations are available in English.

Speaking about the birth of her latest collection of poems, Kerttu ja Hannu (‘Gretel and Hansel’, 2007), the Finnish writer Riina Katajavuori described in her presentation the need to use other words. In her case they were those of poetry, in retelling a tale; here are some extracts (scroll down!). More…

A life at the front

30 September 2001 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Marsipansoldaten (‘The marzipan soldier’, Söderström & Co., 2001). Introduction by Maria Antas

[Autumn 1939]

Göran goes off to the war as a volunteer and gives the Russians one on the jaw. Well, then. First there is training, of course.

Riihimäki town. Recruit Göran Kummel billeted with 145 others in Southern elementary school. 29 men in his dormitory. A good tiled stove, tolerably warm. Tea with bread and butter for breakfast, substantial lunch with potatoes and pork gravy or porridge and milk, soup with crispbread for dinner. After three days Göran still has more or less all his things in his possession. And it is nice to be able to strut up and down in the Civil Guard tunic and warm cloak and military boots while many others are still trudging about in the things they marched in wearing. The truly privileged ones are probably attired in military fur-lined overcoats and fur caps from home, but the majority go about in civilian shirts and jackets and trousers, the most unfortunate in the same blue fine-cut suits in which they arrived, trusting that they would soon be changing into uniform. More…

Poems

30 September 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

The poems of Aleksis Kivi were long considered no more than a peripheral aspect of his work. They were, as Kivi’s friend Kaarlo Bergbom wrote in a review, ‘gold that can’t be minted into coins’. The reason appears to have been Kivi’s poetic technique, which made a clear break with tradition. He did away almost completely with rhyme and instead emphasised the rhythm and musical sound qualities of words. He shortened words in a way that did not find favour with any subsequent Finnish poets. He avoided emotional expressions of patriotism and romantic love poetry; instead, he composed poems that were extended, narrative and fresco-like. Lauri Viljanen, whose 1953 study brought about a re-evaluation of Kivi’s poetry, has given them the apt soubriquet ‘epic idyll’.

The first of Kivi’s poems appeared in the Kirjallinen Kuukauslehti (‘Literary monthly magazine’) in 1866; a collection of his poetry entitled Kanervala was published the same year. Other poems appear in his novels and plays, and some have appeared in a collection after his death. Karhunpyynti (‘The bear hunt’) is from Kanervala. Its descriptive nature is typical of Kivi. The verse structure is tightly controlled but unrhyming. The winter landscape of the third verse, repeated at the end of the poem, is a ceremonious point of rest among the otherwise busy activity.

– Kai Laitinen

![]()

The Bear Hunt

The men on skis set out for the forest, a brave company

With guns and bright spears

And clamouring dogs on the leash,

With blazing eyes,

As the dawn chases gloomy Night

From the sky’s brow,

And the sun raises his head. More…

Figuring out father

18 October 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

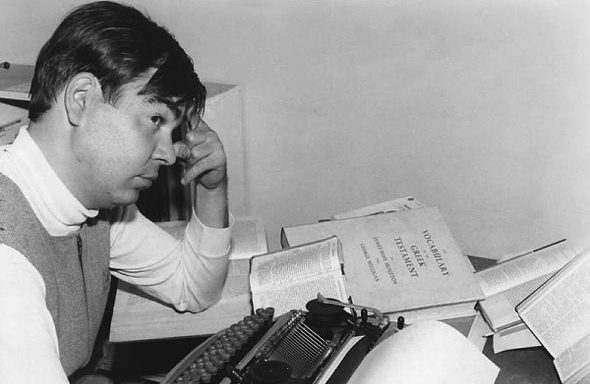

Pentti Saarikoski (1960s). Photo: Otava/Nikolai Naumoff

The poet and translator Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) jotted in one of his journals: ‘I have never cared for relatives.’ Thirty years after his death one of his five children set out to find out what his father was like – by reading almost all he left behind in writing; these comments by Saska Saarikoski are from his Sanojen alamainen (‘Servant of words’, Otava, 2012), an annotated selection of Pentti Saarikoski’s thoughts

Pentti Saarikoski died when I was 19. I remember complaining to my mother that I had not yet even got to know my dad. My mother answered: You’ve got plenty of time, the real Pentti is to be found in his books. She did not know how right she was, for she meant Pentti’s published books, not knowing what a mountain of texts awaited its readers in the archives of the Finnish Literature Society. Pentti had written everything down in his diaries.

I read Nuoruuden päiväkirjat (‘Youthful diaries’), published soon after Pentti’s death in 1983, as soon as they were published, but when his Prague, Drunkard’s and Convalescent’s Diaries appeared around the millennium, they went straight on to my library shelf. I was not terribly interested in the ramblings of Pentti’s alcoholic years.

It could be that my reluctance was influenced by the cool attitude I had adopted from early on in relation to my father. Other people were welcome to consider him a genius; for me, he was a father who did not telephone, write or come to see my football matches. I didn’t call him, either; for me, it was a father’s job. More…

Fight Club

16 April 2012 | Fiction, Prose

A short story from Himokone (‘Lust machine’, WSOY, 2012). Interview by Anna-Leena Ekroos

Karoliina wondered whether her name was suitable for a famous poet.

Her first name was alright – four syllables, and a bit old-fashioned. But Järvi didn’t inspire any passion. Should she change her name before her first collection came out? Was there still time? She had four months until September.

Even if The flower of my secret was the name of some old movie, Karoliina clung to the title she’d chosen. It described the book’s multifaceted, erotically-tinged sensory world and the essential place of nature in the poems. Karoliina loved to take long walks in the woods. Sometimes she talked to the trees.

She had been meeting new people. At the writer’s evening organised by her publisher, she’d been seated next to Märta Fagerlund, in the flesh. Karoliina had read Fagerlund’s poems since her teens, and seen her charisma light up the stage on cultural television shows.

At first Karoliina couldn’t get a word out of her mouth. She just blushed and dripped gravy on her lap. But the longer the evening went on, the more ordinary Märta seemed. She was even calling her Märta, and telling her about a new friend on Facebook who said how ‘awfully funny’ Märta was. In fact, the squeaky-voiced Märta, with her enthusiasm for Greece, was a bit dry, and, after three glasses of white wine, tedious. But Karoliina never mentioned it to anyone, because she wasn’t a spiteful person. More…

Susanne Ringell’s new work is the shortest of the books published in 2000. It easily disappears on the bookshelf if one doesn’t carefully remember where one put it. Only 62 pages. Yet it constructs a whole civilisation and a humanity.

Susanne Ringell’s new work is the shortest of the books published in 2000. It easily disappears on the bookshelf if one doesn’t carefully remember where one put it. Only 62 pages. Yet it constructs a whole civilisation and a humanity.