Search results for "Riikka/2010/10/riikka-pulkkinen-totta-true"

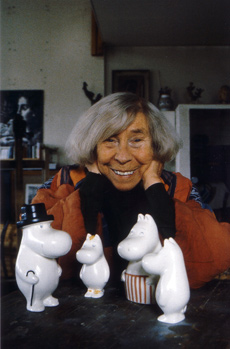

Hip hip hurray, Moomins!

22 October 2010 | This 'n' that

Partying in Moomin Valley: Moomintroll (second from right) dancing through the night with the Snork Maiden (from Tove Jansson’s second Moomin book, Kometjakten, Comet in Moominland, 1946)

The Moomins, those sympathetic, rotund white creatures, and their friends in Moomin Valley celebrate their 65th birthday in 2010.

Tove Jansson published her first illustrated Moomin book, Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen (‘The little trolls and the big flood’) in 1945. In the 1950s the inhabitants of Moomin Valley became increasingly popular both in Finland and abroad, and translations began to appear – as did the first Moomin merchandise in the shops.

Jansson later confessed that she eventually had begun to hate her troll – but luckily she managed to revise her writing, and the Moomin books became more serious and philosophical, yet retaining their delicious humour and mild anarchism. The last of the nine storybooks, Moominvalley in November, appeared in 1970, after which Jansson wrote novels and short stories for adults.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001) was a painter, caricaturist, comic strip artist, illustrator and author of books for both children and adults. Her Moomin comic strips were published in the daily paper the London Evening News between 1954 and 1974; from 1960 onwards the strips were written and illustrated by Tove’s brother Lars Jansson (1926–2000).

Tove’s niece, Sophia Jansson (born 1962) now runs Moomin Characters Ltd as its artistic director and majority shareholder. (The company’s latest turnover was 3,6 million euros).

For the ever-growing fandom of Jansson there is a delightful biography of Tove (click ‘English’) and her family on the site, complete with pictures, video clips and texts.

The world now knows Moomins; the books have been translated into 40 languages. The London Children’s Film Festival in October 2010 featured the film Moomins and the Comet Chase in 3D, with a soundtrack by the Icelandic artist Björk. An exhibition celebrating 65 years of the Moomins (from 23 October to 15 January 2011) at the Bury Art Gallery in Greater Manchester presented Jansson’s illustrations of Moominvalley and its inhabitants.

In association with several commercial partners in the Nordic countries Moomin Characters launched a year-long campaign collecting funds to be donated to the World Wildlife Foundation for the protection of the Baltic Sea. Tove Jansson lived by the Baltic all her life – she spent most of her summers on a small barren island called Klovharu – and the sea featured strongly in her books for both children and adults.

Markus Nummi: Karkkipäivä [Candy day]

26 November 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Karkkipäivä

Karkkipäivä

[Candy day]

Helsinki: Otava, 2010. 383 p.

ISBN 978-951-1-24574-2

€28, hardback

Like this one, Markus Nummi’s previous novel, Kiinalainen puutarha (‘Chinese garden’, 2004), set in Asia at the turn of the 20th century, involves a child’s perspective. Karkkipäivä‘s main theme, however, is a portrait of contemporary Finland. Tomi is a little boy whose alcoholic parents are incapable of looking after him; Mirja’s mother is a frantic workaholic heading for a nervous breakdown. She is a control freak who secretly gorges on chocolate at work and beats her little daughter – a grotesque portrait of contemporary womanhood. Tomi manages to get some adult attention and help from a writer; the relation between them gradually builds into one of trust. Katri is a social worker, empathetic but virtually helpless as part of the social services bureaucracy. Virtually every adult suspects others of lying, finding each other’s motives doubtful. Nummi (born 1959) has structured Karkkipäivä with great skill; the ending, in which matters are resolved almost by chance, is particularly gripping. This novel was nominated for the 2010 Finlandia Prize for Fiction.

A walk on the West Side

16 March 2015 | Fiction, Prose

Hannu Väisänen. Photo: Jouni Harala

Just because you’re a Finnish author, you don’t have to write about Finland – do you?

Here’s a deliciously closely observed short story set in New York: Hannu Väisänen’s Eli Zebbahin voikeksit (‘Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits’) from his new collection, Piisamiturkki (‘The musquash coat’, Otava, 2015).

Best known as a painter, Väisänen (born 1951) has also won large readerships and critical recognition for his series of autobiographical novels Vanikan palat (‘The pieces of crispbread’, 2004, Toiset kengät (‘The other shoes’, 2007, winner of that year’s Finlandia Prize) and Kuperat ja koverat (‘Convex and concave’, 2010). Here he launches into pure fiction with a tale that wouldn’t be out of place in Italo Calvino’s 1973 classic The Castle of Crossed Destinies…

Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits

Eli Zebbah’s small but well-stocked grocery store is located on Amsterdam Avenue in New York, between two enormous florist’s shops. The shop is only a block and a half from the apartment that I had rented for the summer to write there.

The store is literally the breadth of its front door and it is not particularly easy to make out between the two-storey flower stands. The shop space is narrow but long, or maybe I should say deep. It recalls a tunnel or gullet whose walls are lined from floor to ceiling. In addition, hanging from the ceiling using a system of winches, is everything that hasn’t yet found a space on the shelves. In the shop movement is equally possible in a vertical and a horizontal direction. Rails run along both walls, two of them in fact, carrying ladders attached with rings up which the shop assistant scurries with astonishing agility, up and down. Before I have time to mention which particular kind of pasta I wanted, he climbs up, stuffs three packets in to his apron pocket, presents me with them and asks: ‘Will you take the eight-minute or the ten-minute penne?’ I never hear the brusque ‘we’re out of them’ response I’m used to at home. If I’m feeling nostalgic for home food, for example Balkan sausage, it is found for me, always of course under a couple of boxes. You can challenge the shop assistant with something you think is impossible, but I have never heard of anyone being successful. If I don’t fancy Ukrainian pickled cucumbers, I’m bound to find the Belorussian ones I prefer. More…

Teemu Keskisarja: Vihreän kullan kirous. G.A. Serlachiuksen elämä ja afäärit [The curse of green gold. The life and affairs of G.A. Serlachius]

17 March 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Vihreän kullan kirous. G.A. Serlachiuksen elämä ja afäärit

Vihreän kullan kirous. G.A. Serlachiuksen elämä ja afäärit

[The curse of green gold. The life and affairs of G.A. Serlachius]

Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Siltala, 2010. 350 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-234-041-2

€ 35, hardback

In the famine years of the 1860s and with no inherited fortune to his name, G.A. Serlachius (1830–1901) built his industrial centre in the rural backwoods of Mänttä. His work laid the foundations for what would become one of Europe’s leading paper manufacturers. G.A. Serlachius was a Finnish self-made man whose education was cut short due to his family’s financial difficulties. The energetic Serlachius is considered to have pioneered contacts with Western European markets; he was responsible for bringing the first icebreaker ship to Finland. Serlachius was also known as a patron of the arts and a supporter of artists; the collection of the Serlachius Art Foundation is his best-known legacy. According to this biography, Serlachius suffered from ‘an extremely advanced megalomania’ in the opinion of his bankers, and his personality was ‘more aggressive than many Finnish-born generals of the Pax Russica’. The Association of the Friends of History selected this book as its History Book of the Year for 2010.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

Markku Koski: ‘Hohto on mennyt herrana olemisesta’ [‘The glory has gone from being a VIP’]

7 May 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

‘Hohto on mennyt herrana olemisesta’ – Televisio ja poliitikko

‘Hohto on mennyt herrana olemisesta’ – Televisio ja poliitikko

[‘The glory has gone from being a VIP’ – the television and the politician]

Tampere: Vastapaino, 2010. 254 p.

ISBN 978-951-768-249-7

€ 29, paperback

This book, based on the author’s doctoral thesis in Media and Communication Studies at the University of Tampere, presented in February 2010, takes as its starting point Walter Benjamin’s well-known essay, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’. Koski applies Benjamin’s ideas on cinema and film stars to contemporary television and politics. Koski maintains that while the public have become alienated from politics, politicians have also become alienated from themselves and have become reiterative entities whose essential content is repetition. After television and other new media have called into question traditional forms of politics, a significant challenge for politicians has been to prevent viewers from getting bored. Koski discusses relationship between politics and comedy, the ‘cynical’ viewer, the popular public image of Marshal Mannerheim (an iconic figure in Finnish history and politics) and the popularity of Sauli Niinistö, the frontrunner in the upcoming (2012) Finnish presidential election. Dr Koski also considers historical and contemporary image politicians in various other countries.

Hatefully yours

23 December 2011 | Non-fiction, Tales of a journalist

Illustration: Joonas Väänänen

In the new media it’s easy for our pet hatreds to be introduced to anyone who is interested. And of course everyone is interested, how else could it be? Jyrki Lehtola investigates

Twitter, Facebook, Twitter, Twitter, Twitter, Facebook, Twitter, how can we get the revenue model to work by using our old media, Twitter, Facebook, Twitter, Twitter, hey, what about that revenue model of ours, Twitter.

The preceding is a poignant summary of what the Finnish media was like in 2011 when the rules of the game changed like they have changed every year. And we still don’t even fully understand what the game is supposed to be. More…

Georg August Wallin: Skrifter. Band 1 [Writings. Volume 1]

2 December 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Skrifter. Band 1: Studieåren och resan till Alexandria

Skrifter. Band 1: Studieåren och resan till Alexandria

[Writings. Vol. 1: Studies and the journey to Alexandria]

Utg. [Edited by] av Kaj Öhrnberg & Patricia Berg & Kira Pihlflyckt

Helsinki: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 2010. 455 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-583-189-7

ISBN 978-91-7353-371-3 (Bokförlaget Atlantis, Stockholm, 2010)

€ 43, hardback

This is the first volume of a planned six-volume critical edition of the writings of Finnish Arabic scholar Georg August Wallin (1811–1852). The main material for the first volume consists of full text of Wallin’s travel diaries and letters from the years 1831–1843. The Arabic texts are accompanied by parallel Swedish translations. The preface contains an overview of the phases of Wallin’s life and the schools of Orientalism and Rousseau which influenced his work. Wallin’s seven-year research journey to the Middle East, and particularly his crossing of the northern Arabian peninsula as the first Western researcher to do so, brought Wallin great international acclaim. Wallin was the first researcher to record the poetry and study the dialects of the desert Bedouin. He is particularly well known for his visits to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, forbidden to non-Muslims, and to the women’s quarters in their harems.

Cityscapes

23 February 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Photographer Stefan Bremer’s home town, Helsinki, provides endless inspiration, material and atmospheric. For forty years Bremer has been recording views of the maritime city, its changing seasons, its cultural events, its people. These images are from his new book – entitled, simply, Helsinki (Teos, 2012)

City kids: day-care outing in Töölönlahti park. Photo: Stefan Bremer, 2010

When I was a child, Helsinki seemed to me a grey and sad town. Stooping, quiet people walked its broad streets. The colours of the houses had been darkened by coal smoke over the years, and new buildings were coated a depressing grey.

A lot has since changed. Today, Helsinki is younger than it was in my youth. More…

Panem et circenses?

2 February 2012 | This 'n' that

The Guggenheim Foundation's global network of museums

What does Helsinki need? Bread and circuses, yes, but at what cost the latter?

In January – after a study that cost the Finns a couple of million euros – the Salomon R. Guggenheim Foundation (est. 1937) indicated that it was favourably inclined toward the construction of a new art museum, bearing its name, in Helsinki. The leaders of Helsinki city council are aiming to make a positive decision as soon as possible.

The cost of the building, whose site adjoins the Presidential Palace in central Helsinki, is estimated at 130–140 million euros, with design costs of about 11 million euros. Unlike in the case of Berlin, no existing building is considered suitable; instead, an architectural dream must be realised, with plenty of wow-factor.

Its mere maintenance costs will be around 14.5 million euros a year. It has been estimated that the Helsinki Guggenheim’s income could be 7.7 million a year. In addition, a 20-year Guggenheim licence costs 24.6 million euros.

The project has provoked widely differing reactions. Proponents of the project believe that the Guggenheim brand would bring thousands of new visitors to Helsinki and that half a million people would visit it each year. Opponents doubt this, speak of a ‘Guggenburger’ franchising concept and of the fact that not even the existing art museums of Helsinki are particularly crowded.

The odd thing is, however, that the basic demographic differences between Helsinki and, say, Bilbao – where the Guggenheim museum has been a big success – are constantly ignored in the discussions: the population of Spain is almost 50 million and another 50 million visitors go there every year, while the corresponding figures for this most northerly part of Europe are five million inhabitants and visitors.

In Bilbao, moreover, there was no museum of contemporary art before the advent of the Guggenheim; Helsinki, on the other hand, opened Kiasma, a new museum of contemporary art (165,000 visitors in 2010) in 1998 and the neighbouring city of Espoo its Emma museum of modern art (82,000 visitors in 2010) in 2006.

Economic prospects on any level now offer little hope. The Finnish government, in the shape of the ministry of culture, has just cut grants to state-aided museums by three million euros – the Museum of Cultures in Helsinki, for example, is closing its doors, and some 40 of the museum staff elsewhere will be sacked. The government is not promising any money to the Guggenheim.

How, then, to fund an annual deficit of 7 million euros? Finland does not have a great supply of art-minded millionaire sponsors, and no one has so far made any concrete offers on how to fund this project.

The Guggenheim Foundation itself is not taking any financial risks with this project. Neither has it announced in any detail what sort of art will feature in the museum’s temporary exhibitions.

People who live in the city are more preoccupied with, for example, the shortcomings of the health services: there are waiting lists for everything, often of many weeks, and the old university children’s hospital has outgrown its present space. There are cuts and shrinkages yet to come in the spending structure of the country as a whole and of Helsinki – civil servants themselves estimate that the city’s budget is not sufficient to cover even the upkeep of basic services.

To judge by the public debate, the deep ranks of Helsinki taxpayers do not want a new monument, one for which it will be necessary to pay – in addition to maintenance – more than a million euros a year to an American brand for the mere use of its name, for more than 20 years.

Do the people of Helsinki wish to begin to pay additional taxes for the revival, yet again, of the age-old dream of guaranteeing Finland ‘a place on the world map’, in a situation where economic difficulties are a matter of everyday life for increasing numbers of them? (We believe, incidentally, that Finland already has an appropriate place on the world map.) Will their opinion be asked, or heard?

Thunder in the east

31 December 1991 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extract from the novel Colorado Avenue (Söderström & Co, 1991). Introduction by Pia Ingström

Come. We are going to look at schoolmaster Johansson’s photographs.

It is true that Johansson himself died of TB back in 1922, and the collection of glass negatives he left behind – several dozen boxfuls – was destroyed in a peculiar manner. This, however, constitutes no hindrance to us. Where reality falls short, fantasy must intervene. By expanding realistic style beyond the scope of the possible we create a new reality.

To seek to grasp at Time and hold her fast is a dangerous and hopeless undertaking; Time wreaks a terrible revenge on those who seek to rise up against it. Thus, too, was schoolmaster Johansson’s dream of eternity with the help of silver nitrate and glass frustrated. In the spring of 1926 schoolmaster Johansson’s household effects were finally sold by auction. A certain Eskil Holm from Blaxnäs snapped up the glass negatives for a small sum. More…

The bodyguard

31 March 1991 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Henkivartija (‘The bodyguard’), winner of the Runeberg Prize, 1991. Introduction by Suvi Ahola

When spring comes Ossi’s sister tries to reach him on the telephone. She is worried; it sounds as if Ossi is partying constantly. Mostly she is told that Ossi is asleep, Ossi has just gone out, Ossi does not feel like talking. Unknown women call her a whore, tell her to fuck off. In the background she can hear muffled roars, shouts of laughter, music, shouting, the clink of glasses.

Ossi’s sister is irritated to have been left to arrange the practical affairs relating to her father’s death. There will not be much to be had from the smallholding, squeezed between two roads, and the fields have long since been sold. All the same, you might have thought that Ossi would be interested in this possible source of funds; it isn’t as if he has a job, at least not a permanent one. More…

Kullervo

31 March 1989 | Archives online, Drama, Fiction

An extract from the tragedy Kullervo (1864). Introduction by David Barrett

The plot of the Kullervo story as told in the Kalevala: Untamo defeats his brother Kalervo’s army, and Kalervo’s son Kullervo is born a slave. Untamo sells him as a young child to llmarinen whose wife, the Daughter of Pohjola, makes the boy a shepherd and bakes him a loaf with a stone inside it. Kullervo takes his revenge by sending home a flock of wild animals, instead of cattle, who tear her to pieces. He flees, and discovers that his parents and two sisters are alive on the borders of Lapland. He finds them, but one of his sisters is lost. Life in the family home is unhappy: Kullervo fails in all the tasks his father sets him. On his way home one day he finds a girl in the forest whom he abducts in his sledge and seduces. It turns out the girl is his lost sister, who drowns herself when she learns that Kullervo is her brother. Kullervo sets out to revenge himself on Untamo; he kills and destroys. When he returns home, he finds the house empty and deserted, goes into the forest and falls on his sword.

ACT II, Scene 3

Kalervo’s cottage by Kalalampi Lake. It is night-time. Kimmo, seated by a fire of woodchips, is mending nets. More…