Search results for "herbert lomas/www.booksfromfinland.fi/2004/09/no-need-to-go-anywhere"

An end and a beginning

31 March 1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Det har aldrig hänt (‘It never happened’, 1977). Translated and introduced by W. Glyn Jones

There they are!

Over the ice they ride. The hoofs in rhythmical movement kick up the snow. The trail points north west. The sound of the hoofs is absorbed in the blue twilight of a March evening. The two horsemen push on, close together, passing one tiny island after another. Their eyes are fixed on a trail which has lain before them throughout the day. They are hunting like wolves. Yes, like wolves they are.

Or are they?

The twilight gives way to darkness and the black of night. The riders lean low over their horses in an attempt to follow the trail, but at last one of them raises his hand. The hunt is called off. The horses snort and toss their heads so their manes dance. Clouds of steam rise from them, enveloping the men as they dismount and lead their horses to an islet where the dark and deserted profile of a fisherman’s cabin can be glimpsed. Heaven knows who the hut belongs to, but it is a good thing that it is there with its walls and a roof, a shelter against the night. More…

In the Metro

31 December 1995 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extract from the collection of short stories Tidig tvekan (‘Early doubt’, 1938). Introduction by David McDuff

– Mademoiselle! You’re late this evening. Was there overtime again? I’ve put a newspaper aside for you. I saw you were in such a hurry in the morning that you didn’t have time to take it. The fashion page is in today, so I thought you’d like to see it. There’s nothing to thank me for, nothing at all. You see, I seem to have got a bit of a secret liking for you. One gradually learns to pick out all the people who come this way in the morning and go back again at night. And you, you see, I noticed you right from the very first day. You looked so frightened, and then you always smiled at me in such a friendly way. I got the idea that you were someone who wasn’t at home here and who was possibly using the underground in the morning rush hour for the first time. More…

High above the years

23 September 2011 | Fiction, poetry

In Gösta Ågren’s poetry austere aphorisms alternate with concrete observations of life in a small village that was and again is his home, and with portraits of people he has met on his journey in the world. Introduction by David McDuff

Poems from the collection I det stora hela (’On the whole’, Söderströms, 2011)

Father’s hands

(1945)

Father’s hands were like stiff

gloves; a furious

kettle had bewitched them

in his childhood. We ride

from the church’s tall letter

along the river’s long sentence

to the parenthesis of the bridal house,

and the thunder of three hundred hooves

fills the space beneath the clouds.

I saw father driving through

his life with those numbly

gripped reins, and later,

right now, I think of the

life-long body in which a man

comes, is wounded, and goes. More…

Des res

Extracts from the novel Juoksuhaudantie (‘The Trench Road’, WSOY, 2002)

Matti Virtanen

I belonged to that small group of men who were the first in this country to dedicate themselves to the home front and to women’s emancipation. I feel I can say this without boasting and without causing any bickering between the sexes.

A home veteran looks after all the housework and understands women. Throughout our marriage I have done everything that our fathers did not. I did the laundry, cooked the food, cleaned the flat, I gave her time to herself and protected the family from society. For hours on end I listened to her work problems, her emotional ups and downs and her hopes for more varied displays of affection. I implemented comprehensive strategies to free her from the cooker. I was always ready with provisions when she got home exhausted after a day at work. More…

A light shining

28 July 2011 | Essays, Non-fiction

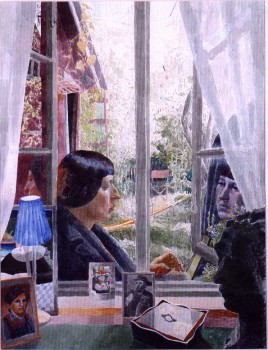

Portrait of the author: Leena Krohn, watercolour by Marjatta Hanhijoki (1998, WSOY)

In many of Leena Krohn’s books metamorphosis and paradox are central. In this article she takes a look at her own history of reading and writing, which to her are ‘the most human of metamorphoses’. Her first book, Vihreä vallankumous (‘The green revolution’, 1970), was for children; what, if anything, makes writing for children different from writing for adults?

Extracts from an essay published in Luovuuden lähteillä. Lasten- ja nuortenkirjailijat kertovat (‘At the sources of creativity. Writings by authors of books for children and young people’, edited by Päivi Heikkilä-Halttunen; The Finnish Institute for Children’s Literature & BTJ Kustannus, 2010)

What is writing? What is reading? I can still remember clearly the moment when, at the age of five, I saw signs become meanings. I had just woken up and taken down a book my mother had left on top of the chest of drawers, having read to us from it the previous day. It was Pilvihepo (‘The cloud-horse’) by Edith Unnerstad. I opened the book and as my eyes travelled along the lines, I understood what I saw. It was a second awakening, a moment of sudden realisation. I count that morning as one of the most significant of my life.

Learning to read lights up books. The dumb begin to speak. The dead come to life. The black letters look the same as they did before, and yet the change is thrilling. Reading and writing are among the most human of metamorphoses. More…

Truth or hype: good books or bad reviews?

8 November 2013 | Letter from the Editors

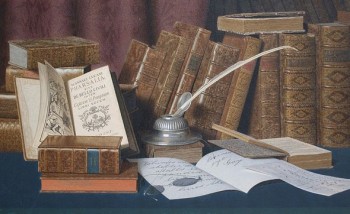

‘The Bibliophile’s Desk’: L. Block (1848–1901). Wikipedia

More and more new Finnish fiction is seeing the light of day. Does quantity equal quality?

Fewer and fewer critical evaluations of those fiction books are published in the traditional print media. Is criticism needed any more?

At the Helsinki Book Fair in late October the latest issue of the weekly magazine Suomen Kuvalehti was removed from the stand of its publisher, Otavamedia, by the chief executive officer of Otava Publishing Company Ltd. Both belong to the same Otava Group.

The cover featured a drawing of a book in the form of a toilet roll, referring to an article entitled ‘The ailing novel’, by Riitta Kylänpää, in which new Finnish fiction and literary life were discussed, with a critical tone at places. CEO Pasi Vainio said he made the decision out of respect for the work of Finnish authors.

His action was consequently assessed by the author Elina Hirvonen who, in her column in the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper, criticised the decision. ‘The attempt to conceal the article was incomprehensible. Authors are not children. The Finnish novel is not doing so badly that it collapses if somebody criticises it. Even a rambling reflection is better for literature than the same old articles about the same old writers’ personal lives.’ More…

Among the ice floes

30 September 1985 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Alpo Ruuth. Photo: Sakari Majantie / Tammi

Alpo Ruuth came across the diary of a member of the Finnish crew of ten men in the Whitbread Round-the-World sailboat race of 1981-1982, and Ruuth, a sailor himself, used that diary as the basis for his novel, 158 vuorokautta (‘158 days’, 1983). It is the story of a great adventure which takes place with the help of ultra-modern equipment and yet involves confrontation with elemental nature, the dangerous power of the southern seas. Ruuth does not use the actual names of the crew, but has taken the view of the fictional crew member who is able to offer ironic comments on what he observes. The book portrays the relationships among the crew under the cramped and difficult conditions of the long voyage. As the extract begins the yacht is in the Southern Ocean, close to the Antarctic coast, making its way towards Auckland, New Zealand.

An extract from 158 vuorokautta (‘158 days’)

Around noon we run into a blizzard. On deck they shout down that a wind has got up. Below, we wake hurriedly from our afternoon naps and start pulling on clothes against the tough weather outside. It’s quite a business in our cramped quarters, and every now and then someone loses his footing and falls as the boat pitches. Cursing is the only medicine for bruises. One by one the boys go up to help change sails; at the bottom of the steps there are excesses of politeness: after you, sir; no no, after you. Up they go, all the same. More…

The pirate’s friend

11 March 2011 | Articles, Non-fiction

Intellectual property was hot stuff half a millennium ago, and not much has changed: Teemu Manninen takes a look at piracy and mercenaries in the age of electronic books

Sir Fulke Greville, 1st Baron Brooke (1554–1628) by Edmund Lodge. Photo: Wikimedia

In November 1586 Fulke Greville (later 1st Baron Brooke) sent Queen Elizabeth’s spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham a letter complaining about some ‘mercenary printers’‘ plans to print the romance novel Arcadia written by his friend (and Walsingham’s son-in-law) Sir Philip Sidney, who had died that very same year. This ‘mercenary book’ needed to be ‘stayed’, i.e. censored by the authorities, so that Sidney’s friends and relatives might take control, and also because publishing his works without consulting Greville or someone close to Sidney might damage his reputation or even his ‘religious honors’.

I rehearse this ancient tale because of its exemplary value for us today. From our point of view there seems nothing extraordinary about Greville’s actions: he is seeking to defend his friend’s literary estate from ‘mercenaries’ who steal intellectual property (IP): pirates. More…

We are the champions

25 March 2011 | Prose

Heroes are still in demand, in sports at least. In his new book author Tuomas Kyrö examines the glorious past and the slightly less glorious present of Finnish sports – as well as the meaning of sports in the contemporary world where it is ‘indispensable for the preservation of nation states’. And he poses a knotty question: what is the difference, in the end, between sports and arts? Are they merely two forms of entertainment?

Heroes are still in demand, in sports at least. In his new book author Tuomas Kyrö examines the glorious past and the slightly less glorious present of Finnish sports – as well as the meaning of sports in the contemporary world where it is ‘indispensable for the preservation of nation states’. And he poses a knotty question: what is the difference, in the end, between sports and arts? Are they merely two forms of entertainment?

Extracts from Urheilukirja (‘The book about sports’, WSOY, 2011; see also Mielensäpahoittaja [‘Taking offence’])

The whole idea of Finland has been sold to us based on Hannes Kolehmainen ‘running Finland onto the world map’. [c. 1912–1922; four Olympic gold medals]. Our existence has been defined by how we are known abroad. Sport, [the Nobel Prize -winning author] F. E. Sillanpää, forestry, [Ms Universe] Armi Kuusela, [another runner] Lasse Viren, Nokia, [rock bands] HIM and Lordi, Martti Ahtisaari.

The purpose of sport at the grass-roots level has been to tend to the health of the nation and at a higher level to take our boys out into the world to beat all the other countries’ boys. We may not know how to talk, but our running endurance is all the better for it. However, the most important message was directed inwards, at our self image: we are the best even though we’re poor; we can endure more than the rest. Finnish success during the interwar period projected an image of a healthy, tenacious and competitive nation; political division meant division into good and bad, the right-minded and traitors to the fatherland. More…

The guest event

12 November 2010 | Fiction, Prose

A short story from Vattnen (‘Waters’, Söderströms, 2010)

It was a lagoon. The water was not like out at sea, not a turquoise dream with white vacation trimming on the crests of the waves. This water was completely still and strange, brown yet clear, sepia and umber, perhaps cinnamon, possibly cigar with the finest flakes of finest wrapper. Clean. This water of meetings was clear and clean in a non-platonic, remarkably earthbound way.

Sediment and humus, humus floating about in the morning sun.

It felt comforting, as if the water didn’t repel the foreign bodies as a matter of course, didn’t immediately suppress the other particles and sanctimoniously hasten to force anything that wasn’t water, anything that could be interpreted as pollution and encroachment, down to the bottom and let it dissolve and die all by itself. This water sang its earth-brown song of unity without thereby becoming any less water than water-water was.

Helena felt cold. More…

I, Vega Maria Eleonora Dreary

30 December 2008 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Chitambo (Schildts, 1933)

I was born in 1893, of course. That, as everyone knows, is the proudest year in the history of Nordic polar research. It was the year in which Fridtjof Nansen began his world-famous voyage to the North Pole aboard the Fram. Mr Dreary viewed this as a personal distinction and a sign that fate had fixed its gaze on him. He at once took it for granted that I was destined for great things, and he showed much skill in fostering the same foolish idea in me…. More…