Search results for "herbert lomas/www.booksfromfinland.fi/2004/09/no-need-to-go-anywhere"

Sex, violence and horror, anyone?

20 September 2012 | Letter from the Editors

Gladiatorial entertainment: Mosaic from the Roman villa at Nennig (Germany), 2nd-3rd century AD. Picture: Wikipedia

In our last Letter, ‘Art for art’s sake’, we pondered how the efforts of making art (or design) profitable and exportable result, in public discourse, in the expectation that art (or design) should aid the development of business.

Not a lot is talked about how business can help art.

Art of course, is in essence ‘no use’, art doesn’t exist in order to increase the GDP (although nothing prevents it from doing so, of course).

The Finnish poet-author-translator Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) argued that art needs no apologies whatsoever: ‘What’s wrong with “Art for art’s sake”? – any more than bread for bread’s sake?

‘Art is art and bread is bread, and people need both if they are to have a balanced diet.’

Defining what is entertainment is and what is art is not always significant or necessary. The boundaries can be artificial, or superficial. But occasionally one wonders where the makers of ‘entertainment’ think it’s going. Entertainment for entertainment’s sake?

The Finnish Broadcasting Company (YLE) recently announced a new radio play series. It is, it said, a series that differs stylistically from traditional radio plays; it seeks a new and younger audience. The news item was headlined: ‘The new radio play drips with sex, violence and horror.’ In a television interview the director said that the radio dramaturge who had commissioned the series had described what the (new, younger) listeners should experience: ‘They should feel thrilled and horny all the time.’ More…

Upstairs, downstairs

31 March 2000 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Harmia lämpöpatterista (‘Trouble with the radiator’, Gummerus, 1999). Introduction by Tero Liukkonen

The view

From here, I can see straight into their bedroom. The thin man chases the red-haired mountain of lard; round and round the room they go: the man is swinging something in his hand, I can’t see what, while the lard-mountain squeals until the man throws her onto the bed. The same thing happens every night; I can’t see the bed. Too low, and I wouldn’t want to, besides; lewd ugly makes me sick that I can even think of it.

Downstairs a young man is always watching TV, sitting there motionless all evening. The blue flickers, never turns on the light, a young man. He has long, slender legs and arms, but his face I can’t see, it’s too dark. There are painting tools on his window sill. More…

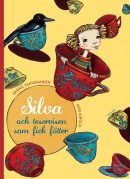

Sanna Tahvanainen & Sari Airola: Silva och teservicen som fick fötter [Silva and the tea set that took to its feet]

13 January 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Silva och teservicen som fick fötter

Silva och teservicen som fick fötter

[Silva and the tea set that took to its feet]

Kuvitus [Ill. by]: Sari Airola

Helsingfors: Schildts, 2011. 32 p.

ISBN 78-951-50-2053-6

€ 21.20, hardback

Silva ja teeastiasto joka sai jalat alleen

Suomennos [Translation from Swedish into Finnish]: Jyrki Kiiskinen

Helsinki: Schildts, 2011. 32 p.

ISBN 978-951-50-2054-3

€ 21.20, hardback

Sari Airola’s ability to depict different emotions makes her one of the most interesting Finnish illustrators of children’s books. Airola has long lived in Hong Kong and one can often sense an oriental spirit in her work. In this book, she makes use of Asian textile printing plates to enliven the surfaces of the images. The subject of this debut children’s book by Tahvanainen (born 1975), who is also a poet and novelist, evokes empathy with family situations that deviate from the norm. Silva lives in a big house with her mother, an isolated control freak and migraine sufferer. When her mother suffers an episode, Silva is unable to establish any contact with her and feels insecure. Although the text is allegorical, the book’s message, which concerns a parent’s caring responsibilities and a child’s need to be loved, remains accessible to children. Once the migraine attack is over, the mother goes out to look for Silva; mother and daughter are reconciled when Silva, at last, puts her fears into words.

Translated by Fleur Jeremiah and Emily Jeremiah

The mighty word

15 November 2012 | Fiction, Prose

‘Mahtisana’, a short story from the collection Lapsia (‘Children’, 1895). Introduction by Mervi Kantokorpi

Mother and Dad hadn’t said a single word to each other since lunchtime. The children, Maija and Iikka, were quiet, too. They sat apart, Iikka on the chair at the end of the sofa, where he could see the moon through the window, and Maija next to the window looking out on the street, where children moved about on skis and sleds. They didn’t dare make a sound, not even a whisper to ask for permission to go outside. It had been so quiet all that Sunday evening that when Mother spoke, encouraging them to go out and play, both of them nearly jumped.

They left without saying a word, Maija creeping quite silently. Even out in the courtyard she and Iikka still spoke in whispers as they decided which hill to go to. They didn’t really want to go anywhere, but when they came out to the street and could hear the happy shouts of children from every direction, it refreshed their spirits. Maija sat Iikka down on the sled and set off at a run, pulling him behind her. She felt as if her gloomy mood was falling away in pieces to be trampled underfoot.

A few streets down there was a large crowd of boys on the corner. They decided to go and see what was happening. More…

Metamorphoses

30 June 1992 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Tummien perhosten koti (‘Home of the dark butterflies’, Kirjayhtymä, 1991). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

The girl is on the rock every evening.

By the side of the sheltered bay, she knits or reads a book. Sometimes she simply lies, motionless, under a large towel, her closed face towards the sun as it sinks into the sea.

She has undone her thick plait. Sometimes her hair lies against the reddish boulder like a fan. As if it had been placed there deliberately.

She does not notice the boy, who can move soundlessly. More…

Eero ja Saimi Järnefeltin kirjeenvaihtoa ja päiväkirjamerkintöjä 1889–1914 [Eero and Saimi Järnefelt: Correspondence and diary entries, 1889–1914]

12 March 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Eero ja Saimi Järnefeltin kirjeenvaihtoa ja päiväkirjamerkintöjä 1889–1914

Eero ja Saimi Järnefeltin kirjeenvaihtoa ja päiväkirjamerkintöjä 1889–1914

[Eero and Saimi Järnefelt: Correspondence and diary entries, 1889–1914]

Toim. [Ed. by] Marko Toppi

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2009. 403 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-113-1

€ 38, hardback

The actress Saimi Swan (1867–1944) and painter Eero Järnefelt (1863–1937) were both born into prominent Finnish families united by similar creative and cultural ideals. The book consists mainly of correspondence between the couple, beginning with their engagement in 1890, and their diary entries up to 1914. Eero Järnefelt’s letters from Paris and Rome provide fascinating glimpses into personal relationships, discussions on artistic practices and aims, and political movements from the golden era of Finnish art. Saimi Järnefelt’s letters illuminate the conflict she experienced between her career and family life. She had to keep her engagement secret in order to safeguard her career; once married, Saimi Järnefelt left the theatre. In letters written to her sister-in-law Aino Sibelius – the wife of composer Jean Sibelius – Saimi Järnefelt often described the cycle of the seasons in her garden: gardening was a hobby the two women shared, in which their need for self-expression could find an outlet.

How Real is a Dead Person?

30 September 1979 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An Extract from the Novel Sirkus (‘Circus’). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Once again I seem to be moving towards a deeper understanding of these people who figure in my recollections, most of whom, by now – by this particular Friday I am now experiencing – are already dead. And this, in its turn, sets me wondering about the degree of reality, if any, that they can claim to possess. How real is a dead person? Is he, perhaps, totally unreal? In memories, of course, he is real to the extent that the memories themselves are real. But objectively, independently of memory? But here a sadness comes over me, many-headed, hard to take hold of.

And in any case I think it is time I came to a clearer understanding of the economic circus founded by my grandfather Feodisius. Uncle Ribodisius has also already made the front pages of the newspapers, and the Bilbao has published an interview.

But I have left a picture unfinished. Father’s cardboard boxes! The separation from Dianita – and from the children! And I have broken off in the middle of these curious memoirs of mine. Thinking of which, I find myself grinding to a halt again, stuck with Yellow-Handed Fred and Haius and Desmer, Lesmer and Sesmer – until I realize that instead of coming to a clearer understanding of my grandfather’s economic circus, I am on Lesmer’s estate, one evening in late May – a couple of months ago – listening to the trilling of an unusually talented song-thrush. Perched on the top of a tall spruce, he goes through the repertoire of all the other birds he has ever heard, both native and foreign – creating, however, new combinations of his own; not content with mere mimicry, he rattles, croons, wails, whistles, whirrs, twitters, flutes, sighs, chirrups and shouts his way through a complete set of variations on themes provided by the rest of the bird world: like some rather advanced medieval chronicler who, no longer content to record faithfully (if perhaps chaotically, as Auerbach points out) what he saw, heard, thought and smelt, had begun to create personal shapes and entities – thus preparing the way for the greatest miracle in the history of world literature, the advent of the perceptive reader. More…

When the viewer vanishes

26 May 2015 | Essays, Non-fiction

For the author Leena Krohn, there is no philosophy of art without moral philosophy

For the author Leena Krohn, there is no philosophy of art without moral philosophy

I lightheartedly promised to explain the foundations of my aesthetics without thinking at any great length about what is my very own that could be called aesthetics. Now I am forced to think about it. The foundations of my possible aesthetics – like those of all aesthetics – lie of course somewhere quite different from aesthetics itself. They lie in human consciousnesses and language, with all the associated indefiniteness.

It is my belief that we do not live in reality, but in metareality. The first virtual world, the simulated Pretend-land is inherent in us.

It is the human consciousness, spun by our own brains, which is shared by everyone belonging to this species. Thus it can be called a shared dream, as indeed I have done. More…

Summer child

30 September 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Resa med lätt bagage (‘Travelling light’, 1987). Introduction by Marianne Bargum

From the very beginning it was quite clear no one at Backen liked him, a thin gloomy child of eleven; he looked hungry somehow. The boy ought to have inspired a natural protective tenderness, but he didn’t at all. To some extent, it was his way of looking at them, or rather of observing them, a suspicious, penetrating look, anything but childish. And when he had finished looking, he commented in his own precocious way, and my goodness, what that child could wring out of himself.

It would have been easier to ignore if Elis had come from a poor home, but he hadn’t. His clothes and suitcase were sheer luxury, and his father’s car had dropped him off at the ferry. It had all been arranged over the phone. The Fredriksons had taken on a summer child out of the goodness of their hearts, and naturally for some compensation. Axel and Hanna had talked about it for a long time, about how town children needed fresh air and trees and water and healthy food. They had said all the usual things, until they had all been convinced that only one thing was left in order to do the right thing and feel at ease. Despite the fact that all the June work was upon them, many of the summer visitors’ boats were still on the slips, and the overhaul of some not even completed. More…

Not joined up

19 February 2015 | In the news

Photo: Brad Flickinger / CC BY 2.0

The news that Finnish schools are to stop teaching cursive writing, in favour of a new emphasis on touch typing and the most efficient way of composing a text message, has been widely reported in the British press.

But not in our household.

With three children – aged 13, 9 and 6 – all struggling, to a greater or lesser degree, to make sense of the curlicues of joined-up writing as it’s taught in British schools, the pressure to abandon school in London and move to Finland would be all but irresistible if they every got to hear the news.

With letter-forms that bear little resemblance to printed characters and a loopy style, apparently derived from old-fashioned copperplate, that few children are going to be able to master completely, let alone develop into an elegant mode of handwriting, joined-up handwriting remains for many an obstacle to, not a means of, communication.

Added to the benefits of Finnish schools my children already know about – the shorter working days, the lighter homework load, the absence of school uniforms, the good school meals, the outdoor breaks every hour – the news that not only will Finnish schoolchildren not be expected to develop good handwriting, but will be issued with tablets on which to practise their computer skills, would axe their enthusiasm for school at home in Britain.

For their mother, the puzzle remains how Finland manages to employ such child-friendly school policies and still remain close to the top of the global Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) assessments. The trick seems to be to recruit top-level graduates into well-run teacher training schemes, pay them well, and to trust them to do their job as teachers, without the mounds of paperwork and need for incessant testing that bedevil the job in Britain.

About the handwriting, my children will find out soon enough, when their friends in Finland come home carrying not exercise books but tablets.

But meanwhile, I’m keeping my fingers crossed they don’t see this piece.

The gender of the soul

Scenes from the play Kuningatar K / Queen C

Characters:

Christina, the Queen

Friend

The Queen Mother

Karl Gustav, the Count [Christina’s suitor, the King-to-be]

Descartes, philosopher

Official

Man

The King

Oxenstierna, Per Brahe

A choir of midwives

The play can be performed with six actors (3 female, 3 male). Other ways of dividing the roles are possible. All stage directions may be altered.

1. Prologue

The eels’ court

CHRISTINA

If eels had a court then a great female eel would sit in the centre and the little males would writhe about like seaweed around the throne. However they would not be envious of the queen, because they would know that if they swam up into rivers and lakes, into fresh waters, they themselves would gradually become females, great and heavy, and would be able to rule and close into their great embrace all the small little gentlemen. They just have to wait.

KARL GUSTAV

I don’t know. What I do know is that a great black eel, as thick as a rope, was pulled out of the well last night and the Queen looked at its silver stomach and its thrashing tail, but the eel looked the Queen in the eyes and in the heart and since then she has never been the same. More…

Helsinki Book Fair 2011

2 November 2011 | In the news

President Toomas Hendrik Ilves at the Book Fair: Viro is Estonia in Finnish. Photo: Kimmo Brandt/The Finnish Fair Corporation

The Helsinki Book Fair, held from 27 to 30 October, attracted more visitors than ever before: 81,000 people came to browse and buy books at the stands of nearly 300 exhibitors and to meet more than a thousand writers and performers at almost 700 events.

The Music Fair, the Wine, Food and Good Living event and the sales exhibition of contemporary art, ArtForum, held at the same time at Helsinki’s Exhibition and Convention Centre, expanded the selection of events and – a significant synergetic advantage, of course – shopping facilities. Twenty-eight per cent of the visitors thought this Book Fair was better than the previous one held in 2010.

According to a poll conducted among three hundred visitors, 21 per cent had read an electronic book while only 6 per cent had an e-book reader of their own. Twenty-five per cent did not believe that e-books will exceed the popularity of printed books, and only three per cent believed that e-books would win the competition.

Estonia was the theme country this time. President Toomas Hendrik Ilves of the Republic of Estonia noted in his speech at the opening ceremony: ‘As we know well from the fate of many of our kindred Finno-Ugric languages, not writing could truly mean a slow national demise. So publish or perish has special meaning here. Without a literary culture, we would simply not exist and we have known this for many generations, since the Finnish and Estonian national epics Kalevala and Kalevipoeg. – During the last decade, more original literature and translations have been published in Estonia than ever before. And we need only access the Internet to glimpse the volume of text that is not printed – it is even larger than the printed corpus. We live in an era of flood, not drought, and thus it is no wonder that as a discerning people, we do not want to keep our ideas and wisdom to ourselves but try to share and distribute them more widely. The idea is not to try to conquer the world but simply, with our own words, to be a full participant in global literary culture, and in the intellectual history and future of humankind.’

Finland meets Estonia: authors Sofi Oksanen and Viivi Luik in discussion. Photo: Kimmo Brandt/The Finnish Fair Corporation