Search results for "jarkko/2009/09/what-god-said"

A toast before dying

30 June 2005 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Voin jo paljon paremmin. Tšehov Badenweilerissa (‘I already feel much better. Chekhov in Badenweiler’, Loki, 2004). Introduction by Hannu Marttila

I went to meet them Friday and I did not plan to take other patients that week. They had a small but comfortable room with striped wallpaper.

The Russian was a tall man, but stooped. It soon became apparent that his wife spoke fluent German because she was of German descent. That made it much easier to take care of things.

Of course I knew who the patient was. I have always enjoyed literature and other forms of art. I could play several pieces rather well on the piano. When I was younger I had even written a couple of stories set in the mountains, though I had never offered them for publication. As for Chekhov, I had read a couple of his stories that had just come out in German translation, and I had liked them quite a lot in a way, even though they of course reflected that characteristic Russian nature, with its vodka and untidiness.

The patient’s wife seized both my hands when I entered. It was a bit confusing, but not necessarily unpleasant.

‘Our name is Chekhov. We have come from Russia,’ the woman said in a strong, carrying voice. ‘I trust you’ve been told?’ More…

A walk on the West Side

16 March 2015 | Fiction, Prose

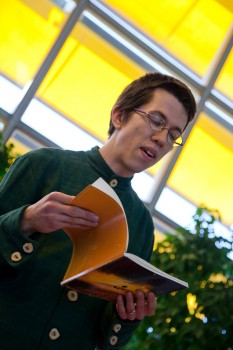

Hannu Väisänen. Photo: Jouni Harala

Just because you’re a Finnish author, you don’t have to write about Finland – do you?

Here’s a deliciously closely observed short story set in New York: Hannu Väisänen’s Eli Zebbahin voikeksit (‘Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits’) from his new collection, Piisamiturkki (‘The musquash coat’, Otava, 2015).

Best known as a painter, Väisänen (born 1951) has also won large readerships and critical recognition for his series of autobiographical novels Vanikan palat (‘The pieces of crispbread’, 2004, Toiset kengät (‘The other shoes’, 2007, winner of that year’s Finlandia Prize) and Kuperat ja koverat (‘Convex and concave’, 2010). Here he launches into pure fiction with a tale that wouldn’t be out of place in Italo Calvino’s 1973 classic The Castle of Crossed Destinies…

Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits

Eli Zebbah’s small but well-stocked grocery store is located on Amsterdam Avenue in New York, between two enormous florist’s shops. The shop is only a block and a half from the apartment that I had rented for the summer to write there.

The store is literally the breadth of its front door and it is not particularly easy to make out between the two-storey flower stands. The shop space is narrow but long, or maybe I should say deep. It recalls a tunnel or gullet whose walls are lined from floor to ceiling. In addition, hanging from the ceiling using a system of winches, is everything that hasn’t yet found a space on the shelves. In the shop movement is equally possible in a vertical and a horizontal direction. Rails run along both walls, two of them in fact, carrying ladders attached with rings up which the shop assistant scurries with astonishing agility, up and down. Before I have time to mention which particular kind of pasta I wanted, he climbs up, stuffs three packets in to his apron pocket, presents me with them and asks: ‘Will you take the eight-minute or the ten-minute penne?’ I never hear the brusque ‘we’re out of them’ response I’m used to at home. If I’m feeling nostalgic for home food, for example Balkan sausage, it is found for me, always of course under a couple of boxes. You can challenge the shop assistant with something you think is impossible, but I have never heard of anyone being successful. If I don’t fancy Ukrainian pickled cucumbers, I’m bound to find the Belorussian ones I prefer. More…

The Conference

31 December 1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Alamaisen kyyneleet (‘Tears of an underdog’, Karisto 1970). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Dr Smith said that he did not believe that any immediate threat of an invasion from Space was likely to arise for some time. Observations to date had given no support to the view that any such preparations had been put in hand. Technically they were of course ahead of us, but in his opinion there was no cause for panic. Nor could he endorse the widespread but naive assumption that any confrontation with beings from Space must inevitably lead to war. If human beings had reason to feel threatened, it was from each other that the chief threat came. He urged the Conference to work for a situation in which every country would be preparing for peace rather than for war. He said he had no wish to sound sardonic, but that he had noticed that when war was prepared for, it was usually war that ensued. More…

For love or money

30 June 1994 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Paratiisitango (‘Paradise tango’, WSOY, 1993). Introduction by Markku Huotari

The bishops’ dilemma

They are waiting for Blume in the front room of the office. On the sofa sits a man whom Blume has never learned to like. He himself chose and appointed the man, for a job not insignificant from the point of view of the company. Blume has good reasons for the appointment. If he employed only men he liked, the business would have gone bankrupt years ago.

Reinhard Kindermann gets up from the sofa and waits in silence while Blume hangs up his overcoat. Mrs Giesler stands next to Blume. She does not try to help her superior take off his coat, for she knows from experience that he would not tolerate it, but the old man does allow her to stand next to him and wait in silence, like a servant expressing submission. More…

Brief lives

30 September 1989 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Rosa Liksom’s characters live in the tiny villages of empty Lapland, speaking a dialect that rings oddly in the ears of the southern Finnish majority; or they may inhabit anonymous towns, but there, too, life is full of the anguish of existence. Liksom, whose black comedy can be compared with that of the Danish writer Vita Andersen, is able to cram into her short texts complete life histories, bizarre, comic or tragic. Her first volume of short stories, Yhden yön pysäkki (‘One night stand’) appeared in 1985; the following short stories are from Tyhjän tien paratiisit (‘Paradises of the open road’, 1989)

We got hitched up the 14th of November and by the end of the month it was all over. As far as I’m concerned call it a marriage exactly two weeks too long. We hadn’t set eyes on each other till the Pampam that’s the place me and the girls go after work for a drink and I was sitting there having one with them when who comes through the door but this bloke and it hits me. That bloke’s for me. In the end I went over to his table and said up yours stud. We went over to my place to bunk down and after that I couldn’t get the sod out. The bloody shitbag got his claws into me and hung on just on the strength of that one night. He glued himself to my bed. Lay there flat out when I set off to work and shit he was still there when I came back only arse up this time. More…

The monster reveal’d

31 March 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Frankensteinin muistikirja (‘Frankenstein’s notebook’, Kirjayhtymä, 1996). Ern(e)st Hemingway and Gertrud(e) Stein – the narrator in these extracts – meet the famous creature in Paris. According to Juha K. Tapio in this, his first novel, Mary Shelley’s monster has been leading an interesting life during the past few centuries

My first impression was that there wasn’t anything particularly monstrous about him. I have already said that his age was hard to determine, but there was something about him that tempted one to apply the word ‘elderly’ to him. He was up in years, no doubt about that, but in a rather special, indefinable way – which made it hard to infer, at least from his outward appearance, what stage he had reached in terms of normal human life. It had to do with something outside of time. He was tall and a little more raw-boned than the average person, and this made one wonder, looking at him, what kind of body his very fashionable clothing concealed his suit and tie conformed to the latest style. This was certainly not the misshapen and monstrous creature I vividly remembered from Mary Shelley’s description.

It was obvious that the past decades had brought about an inevitable evolution. More…

About calendars and other documents

30 June 1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Sudenkorento (‘The dragonfly’, 1970). Introduction by Aarne Kinnunen

I now have. Right here in front of me. To be interviewed. Insulin artist. Caleb Buttocks. I have heard. About his decision. To grasp his nearly. Nonexistent hair and. Lift. Himself and. At the same time. His horse. Out of the swamp into which. He. Claims. He has sunk so deep that. Only. His nose is showing. How is it now, toe dancer Caleb Buttocks. Are you. Perhaps. Or is It your intention. To explain. The self in the world or. The world. In the self. Or is It now that. Just when you. Finally have agreed to. Be interviewed by yourself. You have decided. To go. To the bar for a beer?

– Yes. Can you spare a ten?

– Yes.

– Thanks. See, what’s really happened is that. My hands have started shaking. But when I down two or three bottles of beer, that corpse-washing water as I’ve heard them call it, my hands stop shaking and I don’t make so many typing errors. If I put away six or seven they stop shaking even more and the typing mistakes turn really strange. They become like dreams: all of a sudden you notice you’ve struck it just right. Let’s say, ‘arty’ becomes ‘farty’. Or I mean to say, ‘it strikes me to the core’ I end up typing ‘score’. It’s like that. A friend of mine, an artist, once stuck a revolver in my hand. Imagine, a revolver! I’ve never shot anything with any kind of weapon except a puppy once with a miniature rifle. My God, how nicely it wagged its tail when I aimed at it, but what I’m talking about are handguns, those shiny black steelblue clumps people worship as heaven knows what symbols. It’s not as if I haven’t been hoping to all my life. And now, finally, after I’d waited over fifty years, it turned out that the revolver was a star Nagant, just the kind I’d always dreamed of. So if I ever got one of those, oh, then would sleep through the lulls between shots with that black steel clump ready under my pillow. Well, my friend the artist set out one vodka bottle with a white label and three brown beer bottles with gold labels on the edge of a potato pit – we had just emptied all of them together – stuck the fully loaded star Nagant into my hand, took me thirty yards away and said:

– Oh, Lord. More…

Mothers and sons

30 March 2008 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Helvi Hämäläinen’s novel Raakileet (‘Unripe’, 1950. WSOY, 2007)

In front of the house grew a large old elm and a maple. The crown of the elm had been destroyed in the bombing and there was a large split in the trunk, revealing the grey, rotting wood. But every spring strong, verdant foliage sprouted from the thick trunk and branches; the tree lived its own powerful life. Its roots penetrated under the cement of the grey pavement and found rich soil; they wound their way under the pavement like strong, dark brown forearms. Cars rumbled over them, people walked, children played. On the cement of the pavement the brightly coloured litter of sweet papers, cigarette stubs and apple cores played; in the gutter or even in the street a pale rubber prophylactic might flourish, thrown from some window or dropped by some careless passer-by.

The sky arched blue over the six-and seven-storey buildings; in the evenings a glimmer could be seen at its edges, the reflection of the lights of the city. A group of large stone buildings, streets filled with vehicles, a small area filled with four hundred thousand people, an area in which they were born, died, owned something, earned their daily bread: the city – it lived, breathed….

Six springs had passed since the war…. Ilmari’s eyes gleamed yellow as a snake’s back, he took a dance step or two and bent over Kauko, pretending to stab him with a knife. More…

The fairest in the land

26 January 2012 | Children's books, Fiction

Two fables from Gepardi katsoo peiliin (‘The cheetah looks into the mirror’, Tammi, 2003). Illustrations by Kirsi Neuvonen. (More fables by Hannele Huovi here.)

Two fables from Gepardi katsoo peiliin (‘The cheetah looks into the mirror’, Tammi, 2003). Illustrations by Kirsi Neuvonen. (More fables by Hannele Huovi here.)

Lizard

The air rippled above the pile of stones. The lizard twitched her hip and took up an s-shaped pose like an ordinary photo model. After a moment she changed her left side to a convex curve. The movement was quick and graceful; the lizard’s tail swished through a broad arc so quickly you could hardly see it. Her thin, blistery skin pressed against the surface of the stone. The lizard felt the rough, raised patterns through the thin skin of her belly. She felt unpleasant, but otherwise the place was good, and the lizard did not have the energy to look for a better one. She looked through her eyelashes at the fissured sky and saw the golden disc shining at the centre of the dome. She was happy. Everything in her life was good, the weather was pleasantly dry, the temperature exactly suitable. More…

For the love of a city

31 December 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel I väntan på en jordbävning (‘Waiting for an earthquake’, Söderströms, 2004). Introduction by Petter Lindberg

Nonna Rozenberg lived quite near the special school where I was a boarder, in a block nine stories high with a bas-relief to the right of the door. This bas-relief featured a fairy-tale figure – the Firebird or the Bird Sirin.

I often saw Nonna stepping out of a tram carrying a large brown case. She moved carefully, as if afraid of falling.

She played the cello, and resembled that bulky, melodious instrument herself. Women’s figures are often compared to guitars. But Nonna’s appearance never hinted at parties at home with parents away or singsongs around the camp-fire.

She was no beauty. Her slow, precociously mature body was neither graceful nor girlishly delicate. If I’d met her later, when I was working at a gym, I’d have said she was overweight and lacking in self-discipline. More…

The way to heaven

30 June 1996 | Archives online, Fiction

Extracts from the novel Pyhiesi yhteyteen (‘Numbered among your saints’, WSOY, 1995). Interview with Jari Tervo by Jari Tervo

The wind sighs. The sound comes about when a cloud drives through a tree. I hear birds, as a young girl I could identify the species from the song; now I can no longer see them properly, and hear only distant song. Whether sparrow, titmouse or lark. Exact names, too, tend to disappear. Sometimes, in the old people’s home, I find myself staring at my food, what it is served on, and can’t get the name into my head. The sun came to my grandson’s funeral. It rose from the grave into which my little Marzipan will be lowered. I don’t remember what the weather did when my husband was buried.

A plate. Food is served on a plate. There are deep plates and shallow plates; soups are ladled into the deep ones. More…

In the mirror

30 September 2003 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Helene (WSOY, 2003). Introduction by Leena Ahtola-Moorhouse

It was raining that day, and I was leafing through art books, as I often do, in the bookshop. Then I happened to pick up a work in which there was a picture; a bowl of apples, one of which was black.

Stories often begin like this, inexplicable as deep waters, secret as an unborn child which moves its mouth in the womb as if it wished to speak. For people do not seek mere understanding… people seek the sulphurous, tumultuous shapes of clouds; people seek bowls of apples of which one is black.

I bought the book and made an enlargement of the still life; on the wall, it was even more remarkable, for its correct position was standing up, tête à tête, looking straight at you, unblinking.

The apples seemed to move, to speak. I began to ponder them more and more. In the end I had to read everything I could lay my hands on about the still life’s painter. I had to visit Hyvinkää, where she lived for a long time, and touch her tree in Tammisaari with my hand. I had to travel as far as Brittany to see the rugged landscape that meant so much to her. More…

So close to me

19 August 2010 | Reviews

Please try this first, before we enter the chamber of horrors. It’s a poem by Timo Harju:

… The old people’s home is the strange hand of God with which he strokes

his thinning hair,

a sudden shower of cackling in the dry linen closet, slightly

sad and lonely

God looks out, stirring his cup of tea as if it were on fire.

If Jesus had lived to grow old and gone into an old people’s home,

he would have been like these.

Timo Harju was awarded the 2009 Kritiikin kannukset prize (‘the spurs of criticism’, 2009) of the Finnish Critics' Association, SARV. Photo: Pia Pettersson

This spring a young Finnish female nurse was sentenced to life imprisonment for using insulin to murder a 79-year-old mentally retarded patient. Not long after, sentence was passed on another nurse – this time a meek and submissive-looking middle-aged woman who had murdered a whole series of elderly patients with overdoses of medication.

These are the terms – those of ordinary crime journalism – in which our recent public discussion of long-stay care of the elderly here in Finland was conducted. The discussion was followed by the usual misery of cuts, unchanged diapers, dehydration, over-medication, poor wages for hard work… No wonder that the concept of ‘healthcare wills’ and ‘living wills’, in which people are supposed to say how they want to be cared for in the last stage of their lives – is acquiring a disturbing undertone of ‘better jump before you’re pushed.’ More…

The show must go on

30 June 2007 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Piru, kreivi, noita ja näyttelijä (‘The devil, the count, the witch and the actor’, Gummerus, 2007). Introduction by Anna-Leena Ekroos

‘I hereby humbly introduce the maiden Valpuri, who has graciously consented to join our troupe,’ Henrik said.

A slight girl thrust herself among us and smiled.

‘What can we do with a somebody like her in the group? A slovenly wench, as you see. She can hardly know what acting is,’ Anna-Margareta snapped angrily.

‘What is acting?’ Valpuri asked.

Henrik explained that acting was every kind of amusing trick done to make people enjoy themselves. I added that the purpose of theatre was to show how the world worked, to allow the audience to examine human lives as if in a mirror. Moreover, it taught the audience about civilised behavior, emotional life, and elegant speech. Ericus thought that the deepest essence of theatre was to give visible incarnation to thoughts and feelings. None of us understood what he meant by this, but we nodded enthusiastically. Anna-Margareta insisted that, say what you will, in the end acting was a childish game. Actors were being something they were not, just like children pretending to be little pigs or baby goats. More…