Search results for "jarkko/2011/04/2010/05/2009/10/writing-and-power"

Manmother

31 December 2002 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Granaattiomena (‘Pomegranate’, WSOY, 2002). Introduction by Kristina Carlson

The journey

Mother had sent her son to the island of Rome.

She’d sent him for pleasure and recreation, and also to have a little time by herself. Even though their life together was on an even keel, it was sensible to have some time away from each other. She herself was sixty-eight, and her son an unmarried hermit in his thirties, on sickness allowance for the last couple of years. He was afflicted with chronic depression. The doctors had been unable to identify the cause. The origin of a disorder of that sort was often looked for in some infant trauma; but the boy’s childhood, from all appearances, had been harmonious. One doctor suspected the time of his father’s terminal illness, when the boy had had to nurse his father for a long while. More…

The joy of work

24 October 2011 | Fiction, Prose

Short prose from Sivullisia (‘Outsiders’, Like, 2011). Introduction by Teppo Kulmala

Since I’ve been unemployed, I started a blog called Outsiders. It soon came to serve as work, and I became dependent on its benefits. Although describing being an outsider helped to anaesthetise me, and verbalising all of my afternoons didn’t even take up all my time, the feedback that came in was reward enough. I wouldn’t have taken any other reimbursement anyway because of the restrictions set on recipients of government benefits. Increasingly frequently I found myself longing for more. Even a short blog comment about being an outsider felt even truer than what I with my self-employed, jobless person’s competence was able to achieve in relation to being sidelined as an unemployed person, regardless of what kind of manager I had been in my previous life. When asking for more accounts of other people’s well-being, I wanted them to use their own names. I justified this because I did not want to read lies, which often come from and lead to chatter in cafés and on the web. Apart from the pure enjoyment of being present, using one’s own name – even in wrong-headed topics or notions – makes it easier to approach the harsh laws of the working world. When one knows that by using one’s own signature one is dragging one’s family into the mire, including those who have gone before and those yet to come, one is able to blaze trails along which one can outflank the passive to activate another, equally unemployed. I did not place any further requirements on the other commenters besides first name and surname, as the rules had been drawn up by professionals in their own field. The regulator’s work also requires skill, if not a tremendous craving, for damming up another flood of text so that one’s own advantages do not have a chance to dry up. To facilitate reading for myself and others, I introduced only a couple of restrictions, which I imagined that I, too, would be able to adhere to. Only one side of a sheet of A4 was to be used – that is, one page – and what people wrote had to be true. Truth, beauty and quality ensured that everyone would begin what they had to say by writing about their current work. More stories, anecdotes, even poems piled up than the law permits me to read – much less compile – during working hours. For this book I have selected only 157 stories from the Greater Helsinki area for the sake of efficiency. The faster you can read the work, the less time it will distract you from your main job. I chose to limit things to the capital area so that the stories about well-being from individuals linked to this place would seem to form a more integral work, or document at least, about what was happening in the Big H, the centre of the nation, at the start of the millennium. I will publish the tales of work from beyond the outer ring road at some later stage, if I manage to come to an agreement with the writers concerning intellectual property rights. More…

The trees

31 March 1998 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Sunnuntaina kahdelta (‘Sunday at two’, Otava, 1997)

Maisa enjoyed her trees without knowing their names, without ever counting how many of them there actually were. The trunks twisted together and then forked again, the branches wound round and stretched past each other, and the tapered leaves rustled in dark, wide fans. In the autumn, when the wind blew and the rain fell, the naked stand of trees flailed in a single damp movement, and in February the branches snapped and cracked invisibly under the snow like a promise that would be fulfilled before long.

Sometimes on summer evenings, when the boy was asleep, she listened to the birds fluttering among the shaded lower branches, to the shrews and field mice dashing between the trunks on their nocturnal journeys and the roots pushing deeper into the soil day by day. When she shut her eyes, she could see the sap pulsing under the bark, and her own arms and legs moved more lightly, her heart beat strongly, and her thoughts welled up. More…

How I saved the world for communism

30 September 1996 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Kreisland (WSOY, 1996). Rosa Liksom’s first novel is a picaresque story of a heroine whose adventures range through Finland, Soviet Russia and America. Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

Maid Agafiina: Got myself some shiny black rubber boots, the kind with the red felt lining, and a colorful crepe de chine dress and a rayon coat, and while shopping for all that I checked out the four wonders of Moscow: a bell that doesn’t ring, a cannon you can’t fire, a ruler who doesn’t speak, and money that doesn’t stink.

In no time at all I made up a new personality, learned the language real good, and obtained a Soviet citizen’s passport. I was totally excited by everything I’d seen. My cheeks were as red as the flag. I wanted to find out about everything and see every achievement of this huge Soviet land. More…

The life of a lonely friend

30 September 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Bo Carpelan. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

Extracts from Bo Carpelan‘s novel Axel, ‘a fictional memoir’ (1986). In his preface to the novel Bo explains how he ‘found’ Axel.

Preface

In the 1930s I came across the name of Axel Carpelan (1858-1919), my paternal grandfather’s brother, in Karl Ekman’s Jean Sibelius and His Work (1935). In the bibliography, the author briefly mentions quotes from letters in the book addressed to Axel Carpelan, ‘who belonged to the Master’s most intimate circle of friends, and in musical matters was his constant confidant. Sibelius commemorated their friendship by dedicating his second symphony to him’. I had never heard Axel’s name mentioned in my own family.

Many years after Karl Ekman, the original incentive for the novel about Axel arose through Erik Tawaststjerna’s biography of Sibelius, in which Axel is portrayed in the second volume (1967) of the Finnish edition, and whose life came to an end in Part IV (1978). From early 1970s onwards, I started notes for Axel’s fictional diary from to 1919. It is not known whether Axel himself ever kept a diary. I relied as muchas possible on all the available facts. These increased when I was given access to letters exchanged between Axel and Janne from the year 1900 onwards. It became the story of the hidden strength a very lonely and sick man, and of a friendship in which the give and take both sides was far greater than Axel himself could ever have imagined.

Hagalund, June 1st, 1985

Bo Carpelan

![]()

1878, Axel’s diary

15.1.

On my twentieth birthday, I remember the young Wolfgang; ‘Little Wolfgang has no time to write because he has nothing to do. He wanders up and down the room like a dog troubled by flies’. However, that dog achieved a paradise. I have learnt yet one more piece of wisdom: ‘It is my habit to treat people as I find them; that is the most rewarding in the long run’. More…

To sleep, to die

30 September 2004 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Unelmakuolema (‘Dreamdeath’, Teos, 2004)

Dreamdeath

Who would not like to cheat the grim reaper? Ways are known, of course, both scientific and non-scientific, but all of them are uncertain and temporary. Except for the simplest: to get there first oneself.

The refinement of this idea was Dreamdeath’s business idea. ‘Dreamdeath – because you deserve it!’ went Dreamdeath’s slogan.

The Dreamdeath home offered those who wished it the means to the most pleasant, even luxurious realisation of an autonomic death in an atmosphere of moral approval, against a suitable fee. At Dreamdeath the client himself decided when and in what conditions he would leave his mortal clay. More…

Becoming Finland

23 May 2013 | Reviews

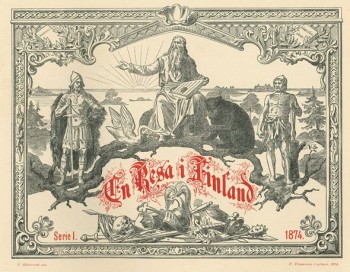

Imaginary heroes: the title page of En resa i Finland. Illustration by C.E. Sjöstrand (1828–1906)

Zacharias Topelius

En resa i Finland

[A journey in Finland (1873)]

Helsinki: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 2013. 173 p., ill.

Utgivare [Editor]: Katarina Pihlflyckt

ISBN 978-951-583-260-3

€38, hardback

(Stockholm: Atlantis förlag, 2013. ISBN 978-91-7353-616-5)

The birth of Finland as a country came as a surprise to those who lived there.

It was created by Napoleon and Alexander I, becoming a reality following Russia’s victory over Sweden in the so called Finnish War. In 1809 Alexander exalted Finland as ‘a nation among nations’, however the new nation still needed to feel like a nation. The Russian rulers supported gentle and non-political nationalism in Finland, in the hope that it would mentally distance the country from Sweden. In this tranquillity, the sense of community they had envisioned grew in Finland.

For this, there were three key factors, all of which stemmed from the 1830s. Elias Lönnrot published the Kalevala, the national epic, proving that Finnish mythology and culture did indeed exist. The poet J.L. Runeberg (who would later become known as the national poet) gave Finland an appearance that was an ideology. He depicted a poor, pious and simple people, a harsh and beautiful wilderness, and with his poems he described the Finnish War, that Finland had lost, as a heroic battle of the people, fought for Finnish values. More…

Asko Sahlberg: Herodes [Herod]

28 November 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Herodes

Herodes

[Herod]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2013. 680 pp.

ISBN 978-951-0-39546-2

€40, hardback

Sahlberg’s short, concise novels about Finland’s recent past are here followed by a massive volume set in the early days of Christianity, in Judea and Galilee. Sahlberg’s accurate use of language, his pithy dialogue and vivid sense of history guarantee a reading experience. John the Baptist is the novel’s great prophet; the short, bow-legged Jeshua remains in his shadow. The main character, however, is Herod Antipas, the Roman tetrarch, and Herod’s wife and his servant are also central. Representing the imperial power in the Judea area is the prefect Pontius Pilate. Herod is a sympathetic character who has, throughout his life, alternately enjoyed and suffered from the use of power. How does power change a man? What is the meaning of trust and loyalty – not to mention love – when life is full of fear, doubt and extortion, poisoners and agitators? Sahlberg (born 1964) also opens up perspectives on the examination of our own time. The novel was on the Finlandia Prize shortlist.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Family mysteries

31 March 2003 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Extracts from Einen keittiö, Eines kök (‘Eine’s kitchen’, Tammi, 2002). Introduction by Satu Koskimies

This sort of detached block of flats is as much of a living organism

as the folk dwelling in it.

For above are the brains and below are the intestines and outlets.

The upper floors were flaunting their kitchen taps, sink-tops,

lion-clawed sofas, mahogany chests and

sapphire-pendant crystal chandeliers, flashing the violet-tones of sea and

rain. More…

Olli Bäckström: Polttolunnaat. Eurooppa sodassa 1618–1630 [Trial by fire. Europe at war 1618–1630]

31 July 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Polttolunnaat. Eurooppa sodassa 1618–1630

Polttolunnaat. Eurooppa sodassa 1618–1630

[Trial by fire. Europe at war 1618–1630]

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura (Finnish Literature Society), 2013. 558 p.

ISBN 978-952-222-394-4

€39, paperback

The Thirty Years War of 1618-48 which ravaged Europe, extending its influence to overseas colonies, has been considered a religious conflict in which several countries were involved for reasons of power politics. Olli Bäckström, who belongs to the younger generation of Finnish military historians, sees the first twelve years of the war as a separate entity that bears similarities to the so-called asymmetric conflicts of our own time, such as those in Africa, which are fought by mercenaries and non-state actors for whom war is an industry and way of life. The book begins by describing the situation in Europe in the early seventeenth century, and the background of the war. Contemporary researchers view it as a religious conflict that originally began in Bohemia and then turned into a political power struggle, but Bäckström sees also the early phase as remarkably nuanced. The Nordic states of Denmark and Sweden (of which Finland was a part) were also in pursuit of fame and power on the battlefields of Central Europe, although Sweden did not really take part in the war until the next phase. Bäckström vividly portrays the alliances formed by the various political actors in order to safeguard their interests, and the methods of warfare employed by the armed forces in the service of the different rulers.

Translated by David McDuff

Star-Eye

31 March 1984 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction

A story from Läsning för barn (‘Reading for children’,1884). Introduction by George C. Schoolfield

There was once a little child lying in a snowdrift. Why? Because it had been lost.

It was Christmas Eve. The old Lapp was driving his sledge through the desolate mountains, and the old Lapp woman was following him. The snow sparkled, the Northern Lights were dancing, and the stars were shining brightly in the sky. The old Lapp thought this was a splendid journey and turned round to look for his wife who was alone in her little Lapp sledge, for the reindeer could not pull more than one person at a time. The woman was holding her little child in her arms. It was wrapped in a thick, soft reindeer skin, but it was difficult for the woman to drive a sledge properly with a child in her arms.

When they had reached the top of the mountain and were just starting off downhill, they came across a pack of wolves. It was a big pack, about forty or fifty of them, such as you often see in winter in Lapland when they are on the look-out for a reindeer. Now these wolves had not managed to catch any reindeer; they were howling with hunger and straight away began to pursue the old Lapp and his wife. More…

Journalist 3.0

22 May 2014 | Non-fiction, Tales of a journalist

Illustration: Joonas Väänänen

As the world becomes more and more difficult to understand, the media, strapped for cash and forced for reduce expenses, sack their expert writers. Jyrki Lehtola assesses the new breed of cut-price journalists

Some time in the distant past it was possible for a reader to reflect that here was an educated journalist writing pithily. It would be nice to know more of his or her thoughts.

There used to be talk of such concepts as the ‘objective truth’, and editors shunned talking about themselves, or even speaking or writing in the first person. There was just the world, which the journalist, the conduit of truth, conveyed to the public.

Now, although most of us would prefer to know nothing about journalists and their private lives, journalists have brought their lives strongly into the public arena. Objectivity is dead; there are merely millions of subjects who perhaps share the same experiences, perhaps not, and, misled by some idealised concept of community, we are the beneficiaries of journalists writing about what it’s like to be a mum, how challenging life as a mother and journalist can be. More…