Search results for "jarkko/2011/04/matti-suurpaa-parnasso-1951–2011-parnasso-1951–2011"

Mishaps, perhaps

30 September 1976 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Jarkko Laine. Photo: Kai Nordberg

Jarkko Laine (born 1947) writes both prose and verse. He is the author of several hilarious and highly imaginative novels and a pioneer of the generation of Finnish underground poets. One of the most productive of younger Finland’s poets, he draws on the language and forms of mass commercial entertainment, comics, and pop music to write about people of today.

He is currently the editorial secretary of the literary periodical Parnasso. The poem below is from his latest collection Viidenpennin Hamlet (‘Fivepenny Hamlet’, Otava 1976)

![]()

1

In Turku again

the taxi’s travelling East Street

whose wooden sides have gone,

the radio’s laryngeal with static, VHF, the driver’s

telling me the tale,

the ice hockey season’s on us already,

even though there’s rain, green in the park,

I’m staring at the lifted houses

stuffed with sleeping persons,

the landmarks are going out one by one, all of them,

you might as well be

in the middle of the sea in a rubber dinghy,

soon I shan’t recognize anything here but

the cathedral, the castle,

my own name in the telephone directory. More…

Matti Yrjänä Joensuu: Harjunpää ja rautahuone [Harjunpää and the iron room]

19 November 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Harjunpää ja rautahuone

Harjunpää ja rautahuone

[Harjunpää and the iron room]

Helsinki: Otava, 2010. 302 p.

ISBN 978-951-1-24742-5

€ 26, hardback

This book’s shocking opening scene, a cot death, is not followed by anything that lightens the tone. Finland’s best-selling crime writer, Matti Yrjänä Joensuu (born 1948) – whose work has been translated into nearly 20 languages – focuses here on a criminal investigation conducted by Inspector Timo Harjunpää into the murderer of several wealthy women. The victims are linked via their purchases of sex; the detective’s attention soon falls on Orvo, a masseur who also turns tricks as a gigolo. Nearly every scene is shot through with themes of lovelessness, exploitation and the connection between malice and sex. Harjunpää is an empathetic, slightly rumpled cop who has an ambitious yet somewhat downbeat attitude to his job. Joensuu’s Harjunpää ja pahan pappi (Priest of Evil) was published in English in 2006. Joensuu himself is a retired police officer; his particular strength as an author is his extraordinarily precise, realistic portrayal of police work. But it’s not just about who did what; why they did it is equally important. One reason for Joensuu’s popularity is his extremely well-developed understanding of human nature. He observes and analyses, but never judges.

Matti Klinge: Suomalainen ja eurooppalainen menneisyys [The Finnish and European past]

8 April 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Suomalainen ja eurooppalainen menneisyys. Historiankirjoitus ja historiankulttuuri keisariaikana

Suomalainen ja eurooppalainen menneisyys. Historiankirjoitus ja historiankulttuuri keisariaikana

[The Finnish and European past. Historiography and history culture in the Imperial era]

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2010. 360 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-208-4

€ 34, hardback

The term ‘Imperial era’ in Finnish history refers to Finland’s period as a Grand Duchy of Russia, 1809–1917. This work is a study of the shaping of Finland’s national culture of history. ‘History culture’ refers to the ways in which ideas about the past are generated, utilised and modified. The brief essays in this book look at the way the past, the events and people involved in historiography are treated in academic research – including those who did not hold high-level academic posts and were therefore absent from previous works. Matti Klinge, an emeritus professor of history, maintains that Finnish historiography has been characterised by an emphasis on nationalism and national development and has focused chiefly on historical writing about Finland. Historians have often been viewed as following in their predecessors’ footsteps, without demonstrating influences acquired from contemporary foreign research. The author emphasises the multilingual intellectual world of the Imperial era; at that time in Finland, people were able to read more foreign languages than nowadays.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

Matti Klinge: Kadonnutta aikaa löytämässä. Muistelmia 1936–1960 [Finding lost time. Memoirs 1936–1960]

10 January 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kadonnutta aikaa löytämässä. Muistelmia 1936–1960

Kadonnutta aikaa löytämässä. Muistelmia 1936–1960

[Finding lost time. Memoirs 1936–1960]

Helsinki: Siltala, 2012. 557 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-234-136-5

€31.95, hardback

Professor (Emeritus) Matti Klinge (born 1936) is a prolific historian who has specialised in the history of culture and ideas as well as in the debate on contemporary culture; he has also published 12 volumes of his diaries. In this fascinating volume of memoirs, inspired by writer Marcel Proust, he gives a detailed account of his childhood, schooldays and military service as well as his years of active study, shedding light on the cultural and social life of his time, from the point of view of Helsinki’s educated bourgeoisie, and draws telling character sketches of his contemporaries. The cultural heritage is reflected in the world of Klinge’s values and in his language. This handsomely produced book contains plenty of illustrative material ranging from entrance tickets and works of art to the jacket pictures of books important to the author and photographs. The volume lacks an index of personal names, which will hopefully be added to the final part of the work.

Translated by David McDuff

One night stand

31 March 1987 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Stories from Yhden yön pysäkki (‘One night stand’, 1985) and Unohdettu vartti (‘The forgotten quarter’, 1986). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

At the beginning of November it really started to freeze. A month earlier than usual. There was little snow to speak of, but the ground froze hard as bone.

Tamed by hunger, reindeer clustered along the roadsides and on the village outskirts. Many of them ended their misery by flinging themselves under the timber-lorries in the evening dark. Bony and bloody carcasses littered the ditches and field-edges.

Then the snowstorms came. It snowed without stop for nearly two weeks. At times the whole landscape was reduced to a white line. Snowdrifts mounted round the houses and up the snow fences. The reindeer carcasses lay about under the snowbanks, waiting for spring. More…

Matti Salminen: Yrjö Kallisen elämä ja totuus [The life and truth of Yrjö Kallinen]

15 September 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Yrjö Kallisen elämä ja totuus

Yrjö Kallisen elämä ja totuus

[The life and truth of Yrjö Kallinen]

Helsinki: Like Kustannus, 2011. 271 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-01-0612-6

€ 27, hardback

Counsellor of Education Yrjö Kallinen (1886–1976) was a Social Democrat politician, a passionate speaker and a pacifist who served for one parliamentary term as an MP and for two years as a cabinet minister. Kallinen was a working-class man who independently acquired a broad general education. His life and thought contain many paradoxes and contradictions. In the Civil War (1918) he received four death sentences, though he tried to act as a peace-broker between the Whites and the Reds. Kallinen avoided the death penalty but suffered a long prison sentence. After the Second World War he became Minister of Defence, though in spite of holding the post he did not abandon his pacifism. Kallinen was also strongly influenced by oriental religions and theosophy, and he is known as an early advocate of vegetarianism. The most important sources for this biography are Yrjö Kallinen’s own writings, many of which have never been published before, and his recently discovered correspondence. The summaries of Kallinen’s interviews for foreign newspapers open up interesting perspectives on recent Finnish political history.

Translated by David McDuff

Matti Rämö: Polkupyörällä Intiassa. Lehmiä, jumalia ja maantiepölyä [Cycling in India. Cows, gods, and road dust]

30 July 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Polkupyörällä Intiassa. Lehmiä, jumalia ja maantiepölyä

Polkupyörällä Intiassa. Lehmiä, jumalia ja maantiepölyä

[Cycling in India. Cows, gods, and road dust]

Helsinki: Minerva Kustannus Oy, 2010. 301 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-492-335-4

€ 27.90, hardback

The author decides to take a pinch of the ashes of his dead mother to India’s Varanasi, the city of pilgrims on the banks of the Ganges, and at the same time visit his daughter at an international high school on the country’s west coast. Rämö takes his bicycle on the plane to Delhi and in the course of a month cycles more than 2,600 kilometres, from Delhi to Mumbai. The cyclist is challenged by the heat and humidity, the chaotic traffic, the awkward sections of road and the endless thirst for knowledge on the part of curious bystanders – but his observations are deeper than those of the average travel author, as he worked in India in third world research during the 1980s and 1990s. In the summer of 2007 he completed a four months’ cycle tour of the Sahara, travelling some 9,600 kilometres, and published a book about his experiences (Rengasrikkoja Saharassa, ‘Punctures in the Sahara’, Minerva, 2008). In spite of the shorter length of the Indian journey, the author thinks it possessed a higher difficulty factor.

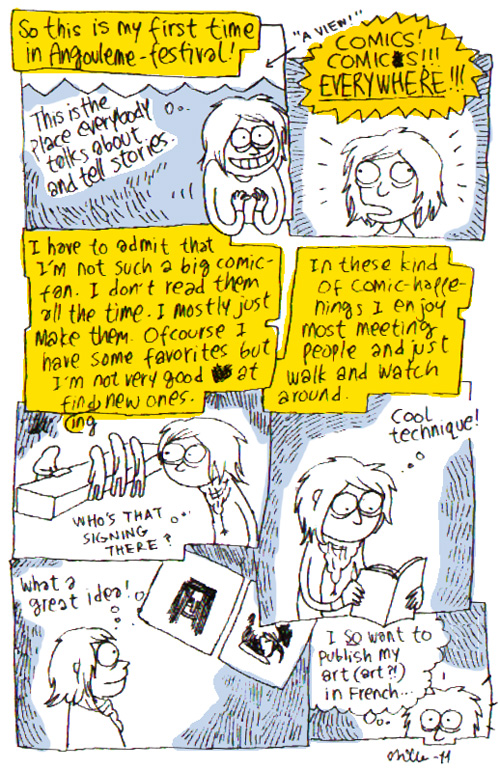

Serious comics: Angoulême 2011

24 February 2011 | This 'n' that

Graphic artist Milla Paloniemi went to Angoulême, too: read more through the link (Milla Paloniemi) in the text below

As a little girl in Paris, I dreamed of going to the Angoulême comics festival – Corto Maltese and Mike Blueberry were my heroes, and I liked to imagine meeting them in person.

20 years later, my wish came true – I went to the festival to present Finnish comics to a French audience! I was an intern at FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange, and for the first time, FILI had its own stand at Angoulême in January 2011.

Finnish comics have become popular abroad in recent years, which is particularly apparent in the young artists’ reception by readers in Europe. Angoulême isn’t just a comics Mecca for Europeans, however: there were admirers of Matti Hagelberg, Marko Turunen and Tommi Musturi from as far away as Japan and Korea.

The festival provides opportunities to present both general ‘official’ comics, ‘out-of-the-ordinary’ and unusual works. The atmosphere at the festival is much wilder than at a traditional book fair: for four days the city is filled with publishers, readers, enthusiasts, artists, and even musicians. People meet in the evenings at le Chat Noir bar to discuss the day’s finds, sketching their friends and the day’s events.

As one Belgian publisher told me, ‘There have always been Finns at Angoulême.’ Staff from comics publisher Kutikuti and many others have been making the rounds at Angoulême for years, walking through the city and festival grounds, carrying their backpacks loaded with books. They have been the forerunners to whom we are grateful, and we hope that our collaboration with them deepens in the future.

Aapo Rapi: Meti (Kutikuti, 2010)

This year two Finnish artists, Aapo Rapi and Ville Ranta were nominated for the Sélection Officielle prize, which gave them wider recognition. Rapi’s Meti is a colourful graphic novel inspired by his own grandmother Meti [see the picture right: the old lady with square glasses].

Hannu Lukkarinen and Juha Ruusuvuori were also favorites, as all the available copies of Les Ossements de Saint Henrik, the French translation of their adventures of Nicholas Grisefoth, sold out. There were also fans of women comics artists, searching feverishly for works by such artists as Jenni Rope and Milla Paloniemi.

Chatting with French publishers and readers, it became clear that Finnish comics are interesting for their freshness and freedom. Finnish artists dare to try every kind of technique and they don’t get bogged down in questions of genre. They said so themselves at the festival’s public event. According to Ville Ranta, the commercial aspect isn’t the most important thing, because comics are still a marginalised art in Finland. Aapo Rapi claimed that ‘the first thing is to express my own ideas, for myself and a couple of friends, then I look to see if it might interest other people.’

Hannu Lukkarinen emphasised that it’s hard to distribute Finnish-language comics to the larger world: for that you need a no-nonsense agent like Kirsi Kinnunen, who has lived in France for a long time doing publicity and translation work. Finnish publishers haven’t yet shown much interest in marketing comics, but that may change in the future.

These Finnish artists, many of them also publishers, were happy at Angoulême. Happy enough, no doubt, to last them until next year!

Translated by Lola Rogers

Living inside language

23 February 2010 | Essays, Non-fiction

Jyrki Kiiskinen sets out on a journey through seven collections of poetry that appeared in 2009. Exploring history, verbal imagery and the limits of language, these poems speak – ironically or in earnest – about landscapes, love and metamorphoses

The landscape of words is in constant motion, like a runner speeding through a sweep of countryside or an eye scaling the hills of Andalucia.

The proportions of the panorama start to shift so that sharp-edged leaves suddenly form small lakeside scenes; a harbour dissolves into a sheet of white paper or another era entirely. Holes and different layers of events begin to appear in the poems. Within each image, another image is already taking shape; sensory experiences develop into concepts, and the text progresses in a series of metamorphoses. More…

The Finlandia prizes: Non-fiction, Junior

28 November 2013 | In the news

Ville Kivimäki. Photo: Pertti Nisonen

The Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2013, worth €30,000, was awarded on 21 November to the historian Ville Kivimäki for his book Murtuneet mielet. Taistelu suomalaissotilaiden hermoista 1939–1945 (‘Broken minds. The battle ofor the nerves of Finnish soldiers 1939–1945’, WSOY).

The other works on the shortlist of six were as follows: 940 päivää isäni muistina (‘940 days as my father’s memory’, Teos; a book on Alzheimer’s disease) by Hanna Jensen, Kokottien kultakausi: Belle Epoquen mediatähdet modernin naiseuden kuvastimina (‘The golden era of the cocottes: the media stars of Belle Epoque as mirrors of modern femininity’, Finnish Literature Society) by Harri Kalha, Viipuri 1918 (‘Vyborg 1918’, Siltala) by Teemu Keskisarja, Suomi öljyn jälkeen (‘Post-oil Finland’, Into) by Rauli Partanen, Harri Paloheimo and Heikki Waris and Vapaalasku – tieto, taito, turvallisuus (‘Freestyle – knowledge, skill, safety’, Kustannus Oy Vapaalasku) by Matti Verkasalo, Jarkko-Juhani Henttonen and Kai Arponen.

The prize-winner was chosen by the director of the Ateneum Art Museum, Maija Tanninen–Mattila. In her celebratory speech she said: ‘The symptoms of many psychologically disturbed soldiers remained untreated during the war. For many, their symptoms appeared only after the war. Their experiences have remained unexpressed in language, the history of those who lack history. Ville Kivimäki has given voice to these experiences… and succeeded in writing a book that speaks across the generations.’

In his acceptance speech Ville Kivimäki (born 1976) commented: ‘The great majority of the war generation is now dead, and the words of a youngish scholar cannot, even when successful, reach those traumatic experiences whose depth we can never fully understand. But all the same, I would like to take this opportunity to say something that should have been said years ago: the psychological injuries of the war were war wounds in exactly the same sense as physical ones. In the end anyone could suffer a psychological breakdown.’

Kreetta Onkeli. Photo: Jouni Harala

The Finlandia Junior Prize 2013 was awarded on 26 November, also worth €30,000. It went to Kreetta Onkeli for her book Poika joka menetti muistinsa (‘The boy who lost his memory’, Otava).

Arto, 12, gets such a massive fit of laughter that he loses his memory and needs to find his identity and his home in contemporary Helsinki.

The winner was chosen from the shortlist of six by Jarno Leppälä, a media personality and member of the popular stunt group Duudsonit, the Dudesons. At the award ceremony he said:

‘Poika joka menetti muistinsa is, in my opinion, a well-written story about how young people in society are put on the same starting line and expected to do equally well in all circumstances – often irrespective of the fact that their starting points may actually be very different, and completely independent of the young people themselves.’

Kreetta Onkeli (born 1970) explained in her award speech how her aim was to write a proper, old-fashioned novel for children: ‘Not hundreds of pages of magic tricks but ordinary, real contemporary life that children could identify with.’ In her opinion the current, massive trend of fantasy has narrowed the scope of children’s literature.

The following five books made it on to the shortlist: Poika (‘The boy’, Like), about a boy who feels he was born in the wrong gender by Marja Björk, Hipinäaasi, apinahiisi (onomatopoetic pun, ‘Donkeymonkey’, Tammi), about bullying and friendship, written by Ville Hytönen and illustrated by Matti Pikkujämsä, Isä vaihtaa vapaalle (‘Father on his own time’, WSOY), an illustrated story about children with too busy parents, written by Jukka Laajarinne and illustrated by Timo Mänttäri, Aapine (‘ABC’, Otava), an illustrated primer written by Heli Laaksonen in her own south-western dialect and illustrated by Elina Warsta and Vain pahaa unta (‘Just a bad dream’, WSOY) by graphic designer and writer Ville Tietäväinen and his daughter Aino, a book on a child’s nightmares.

Finlandia literary prizes are awarded by Suomen Kirjasäätiö, The Finnish Book Foundation, established in 1983.

The first Finlandia Prize for Fiction was awarded in 1984. This year it will be announced on 3 December.

Form follows fun

4 December 2012 | Non-fiction, Reviews

The house that the artist built: ‘Life on a leaf’ (2005–2009, Turku). Photo: Vesa Aaltonen

Jan-Erik Andersson: Elämää lehdellä [Life on a leaf]

Helsinki: Maahenki, 2012. 248 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-5872-82-4

€42, hardback

‘I am Leaf House –

root house, sky house.

Enter me, be safe

And wander, dream.

The artist’s I is all our eyes….’

In the garden: red ‘apple’ benches designed by the English artist Trudy Entwistle. Photo: Matti A. Kallio

We all live – exceptions are really rare – in cubes. Not in cylinders or spheres, let alone in buildings of organic shapes like flowers or leaves; and houses in the shape of a shoe, for example, belong to the fairy-tale world, or perhaps to surrealism.

Artist Jan-Erik Andersson wanted to build a fairy-tale house in the shape of a leaf, and that is what he did (2005–2009), together with his architect partner Erkki Pitkäranta. Instead of the geometry of modernist architecture, he is inspired by the organic forms of nature.

Andersson’s house project, entitled ‘Life on a leaf’, also became an academic project, resulting in a dissertation at Finnish Academy of Fine Arts and now a book, including a detailed journal of the building process itself. The artist was at first advised, by a professor of architecture, not to proceed with his building project – he wouldn’t ‘like living in the house’, he was told. More…

Snowbirds

2 November 2011 | Extracts, Non-fiction

The short winter days of the northerly latitudes are made brighter by snow cover, which almost doubles the amount of available light. Reflection from the snow is an aid for photographers working outdoors in winter conditions. A new book, entitled Linnut lumen valossa (‘Birds in the light of snow’), presents the best shots by four professionals, Arto Juvonen, Tomi Muukkonen, Jari Peltomäki and Markus Varesvuo, who specialise in patiently stalking the feathered survivors in the cold

The photographs and texts are from the book Linnut lumen valossa (‘Birds in the light of snow’, edited by Arno Rautavaara. Design and layout by Jukka Aalto/Armadillo Graphics. Tammi, 2011)

Snowy owl. Photo: Markus Varesvuo, 2010

Finlandia Prize candidates 2011

17 November 2011 | In the news

The candidates for the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011 are Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Kristina Carlson, Laura Gustafsson, Laila Hirvisaari, Rosa Liksom and Jenni Linturi.

The candidates for the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011 are Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Kristina Carlson, Laura Gustafsson, Laila Hirvisaari, Rosa Liksom and Jenni Linturi.

Their novels, respectively, are Kallorumpu (‘Skull drum’, Teos), William N. Päiväkirja (‘William N. Diary’, Otava), Huorasatu (‘Whore tale’, Into), Minä, Katariina (‘I, Catherine’, Otava), Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY) and Isänmaan tähden (‘For fatherland’s sake’, Teos).

Kallorumpu takes place in 1935 in Marshal Mannerheim’s house in Helsinki and in the present time. Laila Hirvisaari is a popular writer of mostly historical fiction: Minä, Katariina, a portrait of Russia’s Catherine the Great, is her 39th novel. Gustafsson’s and Linturi’s novels are first works; the former is a bold farce based on women’s mythology, the latter is about guilt born of the Second World War.

The jury – journalist and critic Hannu Marttila, journalist Tuula Ketonen and translator Kristiina Rikman – made their choice out of 130 novels. The winner, chosen by the theatre manager of the KOM Theatre Pekka Milonoff, will be announced on the first of December. The prize is worth 30,000 euros. It has been awarded since 1984, to novels only from 1993.

The fact that this time all the candidates are women has naturally been the object of criticism: why are the popular male writers’ books of 2011 missing from the list?

Another thing that these novels share is history: five of them are totally or partially set in the past – Finland in 1935, Paris in the 1890s, Russia/Soviet Union in the 18th century and in the 1980s, and 1940s Finland during the Second World War. Even the sixth, Huorasatu, bases its depiction of the present day in women’s prehistory, patriarchy and the ancient myths.

The jury’s chair, Hannu Marttila, commented: ‘This book year is sure to be remembered for a generational and gender change among those who write literature about the Second World War in Finland. Young woman writers describe the war with probably greater diversity than before. From the non-fiction writing of recent years it is clear that the struggles and difficulties of the home front are increasingly being recognised as part of the general struggle for survival, and on the other hand the less heroic aspects of war, the shameful and criminal elements, have also become acceptable as objects of study.’

Marttila concluded his speech: ‘When picking mushrooms in the forest, I have learned that it is often worth humbly peeking under the grass, and that the most glaring cap is not necessarily the best…. Perhaps it is time to forget the old saying that there is literature, and then there is women’s literature.’