Search results for "jarkko/2011/04/matti-suurpaa-parnasso-1951–2011-parnasso-1951–2011"

Findians, Finglish, Finntowns

16 May 2013 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Workers, miners, loggers, idealists, communists, utopians: early last century numerous Finns left for North America to find their fortune, settling down in Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Ontario. Some 800,000 of their descendants now live around the continent, but the old Finntowns have disappeared, and Finglish is fading away – that amusing language cocktail: äpylipai, apple pie.

The 375th anniversary of the arrival of the first Finnish and Swedish settlers, in Delaware, was celebrated on 11 May. Photographer Vesa Oja has met hundreds of American Finns over eight years; the photos and stories are from his new book, Finglish. Finns in North America

Drinking with the workmen: The Työmies Bar. Superior, Wisconsin, USA (2007)

The Työmies Bar is located in the former printing house of the Finnish leftist newspaper, Työmies (‘The workman’). The owners, however, don’t know what this Finnish word means, or how to pronounce it.

The Työmies Society, which published the newspaper of the same name, Työmies, was founded in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1903 as a socialist organ. It moved to Hancock, Michigan the following year. More…

Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011

1 December 2011 | In the news

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011, worth €30,000, is Rosa Liksom, for her novel Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY): read translated extracts and an introduction of the author here on this page.

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011, worth €30,000, is Rosa Liksom, for her novel Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY): read translated extracts and an introduction of the author here on this page.

The prize was awarded on 1 December. The winner was selected by the theatre manager Pekka Milonoff from a shortlist of six.

‘Hytti nro 6 is an extraordinarily compact, poetic and multilayered description of a train journey through Russia. The main character, a girl, leaves Moscow for Siberia, sharing a compartment with a vodka-swilling murderer who tells hair-raising stories about his own life and about the ways of his country. – Liksom is a master of controlled exaggeration. With a couple of carefully chosen brushstrokes, a mini-story, she is able to conjure up an entire human destiny,’ Milonoff commented.

Author and artist Rosa Liksom (alias Anni Ylävaara, born 1958), has since 1985 written novels, short stories, children’s book, comics and plays. Her books have been translated into 16 languages.

Appointed by the Finnish Book Foundation, the prize jury (journalist and critic Hannu Marttila, journalist Tuula Ketonen and translator Kristiina Rikman) shortlisted the following novels: Kallorumpu (‘Skull drum’, Teos) by Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, William N. Päiväkirja (‘William N. Diary’, Otava) by Kristina Carlson, Huorasatu (‘Whore tale’, Into) by Laura Gustafsson, Minä, Katariina (‘I, Catherine’, Otava) by Laila Hirvisaari, and Isänmaan tähden (‘For fatherland’s sake’, first novel; Teos) by Jenni Linturi.

Rosa Liksom travelled a great deal in the Soviet Union in the 1980s. She said she hopes that literature, too, could play a role in promoting co-operation between people, cultures and nations: ‘For the time being there is no chance of some of us being able to live on a different planet.’

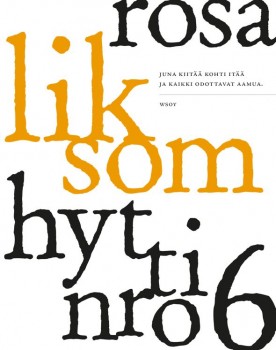

Best Translated Book Award 2011

13 May 2011 | In the news

Thomas Teal’s translation from Swedish into English of Tove Jansson’s novel Den ärliga bedragaren (Schildts, 1982), entitled The True Deceiver (published by New York Review Books, 2009), won the 2011 Best Translated Book Award in fiction (worth $5,000; supported by Amazon.com). The winning titles and translators for this year’s awards were announced on 29 April in New York City as part of the PEN World Voices Festival.

Thomas Teal’s translation from Swedish into English of Tove Jansson’s novel Den ärliga bedragaren (Schildts, 1982), entitled The True Deceiver (published by New York Review Books, 2009), won the 2011 Best Translated Book Award in fiction (worth $5,000; supported by Amazon.com). The winning titles and translators for this year’s awards were announced on 29 April in New York City as part of the PEN World Voices Festival.

Organised by Three percent (the link features a YouTube recording from the award ceremony, introducing the translator, Thomas Teal [fast-forward to 7.30 minutes]) at the University of Rochester, and judged by a board of literary professionals, the Best Translated Book Award is ‘the only prize of its kind to honour the best original works of international literature and poetry published in the US over the previous year’. ‘Subtle, engaging and disquieting, The True Deceiver is a masterful study in opposition and confrontation’, said the jury.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001), mother of the Moomintrolls, story-teller and illustrator of children’s books, translated into 40 languages, began to write novels and short stories for adults in her later years. Psychologically sharp studies of relationships, they are written with cool understatement and perception.

Quality writing will work its way into a wider knowledge (i.e. a bigger language and readership) eventually… even though occasionally it may seem difficult to know where exactly it comes from; in a review published in the London Guardian newspaper, the eminent writer Ursula K. Le Guin assumed Tove Jansson was Swedish.

Government Prize for Translation 2011

24 November 2011 | In the news

María Martzoúkou. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

The Finnish Government Prize for Translation of Finnish Literature of 2011 – worth € 10,000 – was awarded to the Greek translator and linguist María Martzoúkou.

Martzoúkou (born 1958), who lives in Athens, where she works for the Finnish Institute, has studied Finnish language and literature as well as ancient Greek at the Helsinki University, where she has also taught modern Greek. She was the first Greek translator to publish translations of the Finnish epic, the Kalevala: the first edition, containing ten runes, appeared in 1992, the second, containing ten more, in 2004.

‘Saarikoski was the beginning,’ she says; she became interested in modern Finnish poetry, in particular in the poems of Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983). As Saarikoski also translated Greek literature into Finnish, Martzoúkou found herself doubly interested in his works.

Later she has translated poetry by, among others, Tua Forsström, Paavo Haavikko, Riina Katajavuori, Arto Melleri, Annukka Peura, Pentti Saaritsa, Kirsti Simonsuuri and Caj Westerberg.

Among the Finnish novelists Martzoúkou has translated are Mika Waltari (five novels; the sixth, Turms kuolematon, The Etruscan, is in the printing press), Väinö Linna (Tuntematon sotilas, The Unknown Soldier) and Sofi Oksanen (Puhdistus, Purge).

María Martzoúkou received her award in Helsinki on 22 November from the minister of culture and sports, Paavo Arhinmäki. Thanking Martzoúkou for the work she has done for Finnish fiction, he pointed out that The Finnish Institute in Athens will soon publish a book entitled Kreikka ja Suomen talvisota (‘Greece and the Finnish Winter War’), a study of the relations of Finland and Greece and the news of the Winter War (1939–1940) in the Greek press, and it contains articles by Martzoúkou.

The prize has been awarded – now for the 37th time – by the Ministry of Education and Culture since 1975 on the basis of a recommendation from FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange.

See the big picture?

9 November 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Details from the cover, graphic design: Työnalle / Taru Staudinger

In his new book Miksi Suomi on Suomi (‘Why Finland is Finland’, Teos, 2012) writer Tommi Uschanov asks whether there is really anything that makes Finland different from other countries. He discovers that the features that nations themselves think distinguish them from other nations are often the same ones that the other nations consider typical of themselves…. In Finland’s case, though, there does seem to be something that genuinely sets it apart: language. In these extracts Uschanov takes a look at the way Finns express themselves verbally – or don’t

Is there actually anything Finnish about Finland?

My own thoughts on this matter have been significantly influenced by the Norwegian social scientist Anders Johansen and his article ‘Soul for Sale’ (1994). In it, he examines the attempts associated with the Lillehammer Winter Olympics to create an ‘image of Norway’ fit for international consumption. Johansen concluded at the time, almost twenty years ago, that there really isn’t anything particularly Norwegian about contemporary Norwegian culture.

There are certainly many things that are characteristic of Norway, but the same things are as characteristic of prosperous contemporary western countries in general. ‘According to Johansen, ‘Norwegianness’ often connotes things that are marks not of Norwegianness but of modernity. ‘Typically Norwegian’ cultural elements originate outside Norway, from many different places. The kind of Norwegian culture which is not to be found anywhere else is confined to folk music, traditional foods and national costumes. And for ordinary Norwegians they are deadly boring, without any living link to everyday life. More…

Finlandia Junior Prize 2011

7 December 2011 | In the news

The musician Paula Vesala has chosen, from a shortlist of six, a book for young people by the poet Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen, Valoa valoa valoa (‘Light light light’, Karisto). The story, which is set at the time of the Chernobyl nuclear power station disaster, poetically describes the passion and pain of first love, longing for mother and death.

The musician Paula Vesala has chosen, from a shortlist of six, a book for young people by the poet Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen, Valoa valoa valoa (‘Light light light’, Karisto). The story, which is set at the time of the Chernobyl nuclear power station disaster, poetically describes the passion and pain of first love, longing for mother and death.

‘Not just what is told, but how it is told. The rythm and timbre of Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen’s language are immensely beautiful. Her phrases do not exist merely to tell the story, but live like poetry or song. Valoa valoa valoa does not incline toward young people from the world of adults; rather, its voice comes, direct and living, from painful, confusing, complex youth, in which young people should really be protected from adults and their blindness. I would have liked to read this book when I was fourteen,’ commented Vesala.

The other five shortlisted books were a picture book for small children, Rakastunut krokotiili (‘Crocodile in love’, Tammi) by Hannu Hirvonen & Pia Sakki, a philosophical picture book about being different and courageous entitled Jättityttö ja Pirhonen (‘Giant girl and Pirhonen’, Tammi) by Hannele Huovi and Kristiina Louhi; a dystopic story set in the 2300s, Routasisarukset (‘Sisters of permafrost’, WSOY), by Eija Lappalainen & Anne Leinonen; a novel about the war experiences of an Ingrian family, Kaukana omalta maalta (‘Far away from homeland’, WSOY) by Sisko Latvus and an illustrated book about gods and myths of the world, Taivaallinen suurperhe (‘Extended heavenly family’, Otava) by Marjatta Levanto & Julia Vuori.

The prize, awarded by the Finnish Book Foundation on 23 November, is worth €30,000.

In memoriam Herbert Lomas 1924–2011

23 September 2011 | In the news

Herbert Lomas. Photo: Soila Lehtonen

Herbert Lomas, English poet, literary critic and translator of Finnish literature, died on 9 September, aged 87.

Born in the Yorkshire village of Todmorden, Bertie lived for the past thirty years in the small town of Aldeburgh by the North Sea in Suffolk. (Read an interview with him in Books from Finland, November 2009.)

After serving two years in India during the war, Bertie taught English first in Greece, then in Finland, where he settled for 13 years. His translations – as well as many by his American-born wife Mary Lomas (died 1986) – were published from as early as 1976 in Books from Finland.

Bertie’s first collection of poetry (of a total of ten) appeared in 1969. His Letters in the Dark (1986) was an Observer book of the year, and he was the recipient of several literary prizes. His collected poems, A Casual Knack of Living, appeared in 2009.

In England Bertie won the Poetry Society’s 1991 biennial translation award for one of his anthologies, Contemporary Finnish Poetry. The Finnish government recognised his work in making Finnish literature better known when it made him a Knight First Class of Order of the White Rose of Finland in 1987.

To Books from Finland, he made an invaluable contribution over almost 35 years – an incredibly long time in the existence of a small literary magazine. The number of Finnish authors and poets whose work he made available in English is countless: classics, young writers, novelists, poets, dramatists.

Bertie’s speciality was ‘difficult’ poets, whose challenge lay in their use of end-rhymes, special vocabulary, rhythm or metre. He loved music, so the sounds and tones of words, their musicality, were among the things that fascinated him. Kirsi Kunnas’ hilarious, limerick-inspired children’s rhymes were among his best translations – although actually nothing in them would make the reader think that the originals might not have been written in English. A sample: There once was a crane / whose life was led / as a uniped. / It dangled its head / and from time to time said:/ It would be a pain / if I looked like a crane. (From Tiitiäisen satupuu, ‘Tittytumpkin’s fairy tree’, 1956, published in Books from Finland 1/1979.)

Bertie also translated work by Eeva-Liisa Manner, Paavo Haavikko, Mirkka Rekola, Pentti Holappa, Ilpo Tiihonen, Aaro Hellaakoski and Juhani Aho among many, many others; for example, the prolific writer Arto Paasilinna’s best-known novel, Jäniksen vuosi / The Year of the Hare, appeared in his translation in 1995. Johanna Sinisalo’s unusually (in the Finnish context) non-realist troll novel Ennen päivänlaskua ei voi / Not Before Sundown, subsequently translated into many other languages, appeared in 2003. His last translation for Books from Finland was of new poems by Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen in 2009.

It was always fun to talk with Bertie about translations, language(s), writers, books, and life in general. He himself said he was a schoolboy at heart – which is easy to believe. He was funny, witty, inventive, impulsive, sometimes impatient – and thoroughly trustworthy: he just knew how to find the precise word, tone of voice, figure of speech. He had perfect poetic pitch. As dedicated and incredibly versatile translators are really hard to find anywhere, we all realise our good fortune – both for Finnish literature and for ourselves – to have worked, and enjoyed with such enjoyment, with Bertie.

Poet Aaro Hellaakoski (1893–1956) was not a self-avowed follower of Zen, but his last poems, in particular, show surprisingly close contacts with the philosophy. ‘Secrets of existence are revealed once one ceases seeking them’, the literary scholar Tero Tähtinen wrote in an essay published alongside Bertie’s new Hellaakoski translations in (the printed) Books from Finland (2/2007). Bertie was fond of Hellaakoski, whose existential verses fascinated him; among his 2007 translations is The new song (from Vartiossa, ‘On guard’, 1941):

The new song |

Uusi laulu |

| No compulsion, not a sting. | Ei mitään pakota, ei polta. |

| My body doesn’t seem to be. | On ruumis niinkuin ei oisikaan. |

| As if a nightbird started to sing | Kuin alkais kaukovainioilta |

| its far shy carol from some tree – | yölintu arka lauluaan |

| as if from its dim chrysalis | kuin hyönteistoukka heräämässä |

| a little grub awoke to bliss – | ois kotelossaan himmeässä |

| or someone struck from off his shoulder | kuin hartioiltaan joku loisi |

| a miserable old bugaboo – | pois köyhän muodon entisen |

| and a weird flying creature | ja outo lentäväinen oisi |

| stretched a fragile wing and flew. | ja nostais siiven kevyen. |

| Ah limitless bright light: | Oi kimmellystä ilman pielen. |

| the gift of lyrical flight! | Oi rikkautta laulun kielen. |

Helsinki Book Fair 2011

2 November 2011 | In the news

President Toomas Hendrik Ilves at the Book Fair: Viro is Estonia in Finnish. Photo: Kimmo Brandt/The Finnish Fair Corporation

The Helsinki Book Fair, held from 27 to 30 October, attracted more visitors than ever before: 81,000 people came to browse and buy books at the stands of nearly 300 exhibitors and to meet more than a thousand writers and performers at almost 700 events.

The Music Fair, the Wine, Food and Good Living event and the sales exhibition of contemporary art, ArtForum, held at the same time at Helsinki’s Exhibition and Convention Centre, expanded the selection of events and – a significant synergetic advantage, of course – shopping facilities. Twenty-eight per cent of the visitors thought this Book Fair was better than the previous one held in 2010.

According to a poll conducted among three hundred visitors, 21 per cent had read an electronic book while only 6 per cent had an e-book reader of their own. Twenty-five per cent did not believe that e-books will exceed the popularity of printed books, and only three per cent believed that e-books would win the competition.

Estonia was the theme country this time. President Toomas Hendrik Ilves of the Republic of Estonia noted in his speech at the opening ceremony: ‘As we know well from the fate of many of our kindred Finno-Ugric languages, not writing could truly mean a slow national demise. So publish or perish has special meaning here. Without a literary culture, we would simply not exist and we have known this for many generations, since the Finnish and Estonian national epics Kalevala and Kalevipoeg. – During the last decade, more original literature and translations have been published in Estonia than ever before. And we need only access the Internet to glimpse the volume of text that is not printed – it is even larger than the printed corpus. We live in an era of flood, not drought, and thus it is no wonder that as a discerning people, we do not want to keep our ideas and wisdom to ourselves but try to share and distribute them more widely. The idea is not to try to conquer the world but simply, with our own words, to be a full participant in global literary culture, and in the intellectual history and future of humankind.’

Finland meets Estonia: authors Sofi Oksanen and Viivi Luik in discussion. Photo: Kimmo Brandt/The Finnish Fair Corporation

Everyday life at the Science Forum 2011

20 January 2011 | In the news

‘Everyday life’ in focus: scientific approaches. Picture: Elina Warsta

This year’s Science Forum took place in Helsinki between 12 and 16 January. This biennial science festival – which has existed in its current format since 1977 – invites a wide audience to lectures, debates, discussions and various other events where scholars introduce their branch of research and science. This time the theme was ‘Science and everyday life’.

The Science Forum is organised by the Federation of Finnish Learned Societies, the Finnish Academies of Sciences and Letters and the Finnish Cultural Foundation.

In Finnish, the word for ‘everyday life’ is arki. Professor of Consumer Economics Visa Heinonen defined arki as follows: ‘Scientifically arki cannot be defined undisputably. An individual experiences the everyday as a ‘stream’ of life. Arki is mostly the recurrence of the small basic elements of life and the constant renewal of the prerequisites of existence. The everyday contains much that is routine as well as small moments of joy. Carpe diem, seize the moment, might be a good guideline to life.’

Among the Forum’s topics were the everyday work of scientific research and its significance for the development of everyday life in society, dimensions of consumer culture, multicultural society, religion, the arts and the media, technological advances in food production and the built environment, future energy sources and the global economy.

The Science Forum attracted 18,000 visitors, in addition to the 3,000 who participated in the Forum via the Internet. The five most popular topics, or sessions, were those entitled ‘Good life’, ‘Ageing as a biological phenomenon’, ‘Nanotechnology changing everyday life’, ‘Sleep – a third of life’ and ‘Food and everyday chemistry’.

Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2011

24 November 2011 | In the news

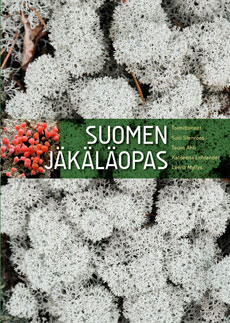

‘Scientific, aesthetic, timely: the work is all of these. A work of non-fiction can be both precisely factual and emotional, full of both information and soul. A good non-fiction book will surprise. I did not expect to be enthused by lichens, their variety and colours,’ declared Professor Alf Reen in announcing the winner of this year’s Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction on 17 November.

‘Scientific, aesthetic, timely: the work is all of these. A work of non-fiction can be both precisely factual and emotional, full of both information and soul. A good non-fiction book will surprise. I did not expect to be enthused by lichens, their variety and colours,’ declared Professor Alf Reen in announcing the winner of this year’s Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction on 17 November.

The winning work is Suomen jäkäläopas (‘Guidebook of lichens in Finland’), edited by Soili Stenroos & Teuvo Ahti & Katileena Lohtander & Leena Myllys (The Botanical Museum / The Finnish Museum of Natural History). The prize is worth €30,000.

The other works on the shortlist of six were the following: Kustaa III ja suuri merisota. Taistelut Suomenlahdella 1788–1790 [(‘Gustav III and the great sea war. Battles in the Gulf of Finland 1788–1790’, John Nurminen Foundation), written by Raoul Johnsson, with an editorial board consisting of Maria Grönroos & Ilkka Karttunen &Tommi Jokivaara & Juhani Kaskeala & Erik Båsk; Unihiekkaa etsimässä. Ratkaisuja vauvan ja taaperon unipulmiin (‘In search of the sandman. Solutions to babies’ and toddlers’ sleep problems’ ) by Anna Keski-Rahkonen & Minna Nalbantoglu (Duodecim); Operaatio Hokki. Päämajan vaiettu kaukopartio (‘Operation Hokki. Headquarters’ silenced long-distance patrol’), an account of a long-distance patrol strike in eastern Karelia during the Continuation War in 1944, by Mikko Porvali (Atena); Trotski (‘Trotsky’, Gummerus; biography) by Christer Pursiainen; and Lintukuvauksen käsikirja (‘Handbook of bird photography’) by Markus Varesvuo & Jari Peltomäki & Bence Máté (Docendo).

Turku, city of culture 2011

21 January 2011 | In the news

Passing the peace: citizens of Turku gathering to listen to the traditional declaration of peace at Christmas in front of the Cathedral. Photo: Esko Keski-oja

Since 1985, cities in the countries of the European Union have been chosen as European Capitals of Culture each year. More than 40 cities have been designated so far; a city is not chosen only for what it is but, more importantly, what it plans to do for year and also for what will remain after the year is over – the intention is that citizens and the local culture should profit from the investments made.

This year the two cities are Tallinn in Estonia and Turku, the oldest city and briefly (1809–1812) the capital of what was then the Grand Duchy of Finland, on the coast, 160 kilometres west of Helsinki. The pair will also co-operate in making this year a special one in their cultural lives.

The city of Turku declared its Cultural Capital year open on 15 January with a massive firework display glittering over the River Aura. This cultural capital enterprise, with a budget of 50 million euros and an ambitious programme will, hopefully, involve two million participants in the five thousand cultural events and occasions.

In pursuit of a conscience

19 March 2012 | Drama, Fiction

‘An unflinching opera and a hot-blooded cantata about a time when the church was torn apart, Finland was divided and gays stopped being biddable’: this is how Pirkko Saisio’s new play HOMO! (music composed by Jussi Tuurna) is described by the Finnish National Theatre, where it is currently playing to full houses. This tragicomical-farcical satire takes up serious issues with gusto. In this extract we meet Veijo Teräs, troubled by his dreams of Snow White, who resembles his steely MP wife Hellevi – and seven dwarves. Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

Dictators and bishops: Scene 15, ‘A small international gay opera’. Photographs: The Finnish National Theatre / Laura Malmivaara, 2011

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Veijo Teräs

Hellevi, Veijo’s wife and a Member of Parliament

Hellevi’s Conscience

Rebekka, Hellevi and Veijo’s daughter

Moritz, Hellevi and Veijo’s godson

Agnes af Starck-Hare, Doctor of Psychiatry

Seven Dwarves

Tom of Finland

Atik

The Bishop of Mikkeli

Adolf Hitler

Albert Speer

Josef Stalin

Old gays: Kale, Jorma, Rekku, Risto

Olli, Uffe,Tiina, Jorma: people from SETA [the Finnish LGBT association]

Second Lieutenant, Private Teräs, the men in the company

A Policeman

Big Gay, Little Gay, Middle Gay

William Shakespeare

Hermann Göring

Hans-Christian Andersen

Teemu & Oskari, a gay couple

The Apostle Paul

Father Nitro

Winston Churchill

SCENE ONE

On the stage, a narrow closet.

Veijo Teräs appears, struggling to get out of the closet.

Veijo Teräs is dressed as a prince. He is surprised and embarrassed to see that the audience is already there. He seems to be waiting for something.

He speaks, but continues to look out over the audience expectantly.

Snow White's spouse, Veijo (Juha Muje), and the dwarves. Photo: Laura Malmivaara, 2011

VEIJO

This outfit isn’t specifically for me, because… I mean, it’s part of this whole thing. This Snow White thing. I’m waiting for the play to start. Just like you are. My name is Veijo Teräs and I’m playing the point of view role in this story. Writers put point of view roles like this in their plays nowadays. They didn’t use to.

Just to be clear – this isn’t a ballet costume. I’m not going to do any ballet dancing, but I won’t mind if someone dances, even if it’s a man. Particularly if it’s a man. But I don’t watch. Ballet, I mean. Not at the opera house, or on television, or anywhere, and I have no idea why we had to bring up ballet – or I had to bring it up – because this is a historical costume, so it’s appropriate. This is what men used to wear, real men like Romeo and Hamlet, or Cyrano de Bergerac. But we in the theatre these days have a hell of a job getting an audience to listen to what a man has to say when he’s standing there saying what he has to say in an outfit like this. People get the idea that it’s a humorous thing, but this isn’t, this Snow White thing, where I play the prince. Snow White is waiting in her glass casket, she died from an apple, which seems to have become the Apple logo, Lord knows why, the one on the laptops you see on the tables of every café in town. More…

The books that sold

11 March 2011 | In the news

-Today we're off to the Middle Ages Fair. – Oh, right. - Welcome! I'm Knight Orgulf. – I'm a noblewoman. -Who are you? – The plague. *From Fingerpori by Pertti Jarla

Among the ten best-selling Finnish fiction books in 2010, according statistics compiled by the Booksellers’ Association of Finland, were three crime novels.

Number one on the list was the latest thriller by Ilkka Remes, Shokkiaalto (‘Shock wave‘, WSOY). It sold 72,600 copies. Second came a new family novel Totta (‘True’, Otava) by Riikka Pulkkinen, 59,100 copies.

Number three was a new thriller by Reijo Mäki (Kolmijalkainen mies, ‘The three-legged man’, Otava), and a new police novel by Matti Yrjänä Joensuu, Harjunpää ja rautahuone (‘Harjunpää and the iron room’, Otava), was number six.

The Finlandia Fiction Prize winner 2010, Nenäpäivä (‘Nose day’, Teos) by Mikko Rimminen, sold almost 54,000 copies and was fourth on the list. Sofi Oksanen’s record-breaking, prize-winning Puhdistus (Purge, WSOY; first published in 2008) was still in fifth place, with 52,000 copies sold.

Among translated fiction books were, as usual, names like Patricia Cornwell, Dan Brown and Liza Marklund.

In non-fiction, the weather, fickle and fierce, seems to be a subject of endless interest to Finns; the list was topped by Sääpäiväkirja 2011 (‘Weather book 2011’, Otava), with a whopping 140,000 copies. Number two was the Guinness World Records 2011, but with just 43,000 copies. Books on wine, cookery and garden were popular. A book on Finnish history after the civil war, Vihan ja rakkauden liekit (‘Flames of hate and love’, Otava) by Sirpa Kähkönen, made it to number 8 on the list.

The Finnish children’s books best-sellers’ list was topped by the latest picture book by Mauri Kunnas, Hurja-Harri ja pullon henki (‘Wild Harry and the genie’, Otava), selling almost 66,000 copies. As usual, Walt Disney ruled the roost in the translated fiction list.

The Finnish comics list was dominated by Pertti Jarla (his Fingerpori series books sold more than 70,000 copies, almost as much as Remes’ Shokkiaalto!) and Juba Tuomola (Viivi and Wagner series; both mostly published by Arktinen Banaani): between them, they grabbed 14 places out of 20!