Search results for "2010/05/song-without-words"

Ulla Jokisalo & Anna Kortelainen

Pins and needles

11 May 2011 | Essays, Non-fiction

In these pictures by Ulla Jokisalo and texts by Anna Kortelainen, truths and mysteries concerning play are entwined with pictures painted with threads and needles. Jokisalo’s exhibition, ‘Leikin varjo / Guises of play’, runs at the Museum of Photography, Helsinki, from 17 August to 25 September.

Words and images from the book Leikin varjo / Guises of play (Aboa Vetus & Ars Nova and Musta Taide, 2011)

‘Ring dance’ by Ulla Jokisalo (pigment print and pins, 2009)

Is it a play, is it a book?

25 February 2011 | This 'n' that

On the way to fame: Walt the Wonder Boy in Kristian Smeds's stage adaptation of Paul Auster's novel Mr. Vertigo at the Finnish National Theatre (2010). Photo: Antti Ahonen

Dramatisations of novels are tricky. Finnish theatremakers like adapting novels for the stage, which often results in a lot of talking instead of action – and action here doesn’t refer to just physical movement but to the subtext, to what happens under and behind the words.

Currently an adaptation of an American novel is running on the main stage of the Finnish National Theatre in Helsinki. Mr Vertigo (1994), Paul Auster’s seventh book, tells the story of an orphan boy in the 1930s St Louis. After harsh years as the long-suffering apprentice of the mysterious Master Yehudi, Walt becomes the sensational Wonder Boy by learning how to levitate.

In theatremaker Kristian Smeds’s adaptation, Auster’s whimsical, rambling novel becomes a capricious, illusory journey about illusions, freedom, and the unattainability of love. Walt (the highly expressive, athletic Tero Jartti) interprets, with hilarious comedy as well as with touching desperation, both the dizzyingly powerful experience of creativity and the ridiculous hubris of the artist. More…

A day in the life

30 September 1996 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Drakarna över Helsingfors (‘Kites over Helsingfors’, Söderströms, 1996). Introduction by Jyrki Kiiskinen

It is December 1970, it is Friday afternoon and Helsingfors is shrouded in a damp, leaden-grey fog when Jacke Pettersson, trainee electrician at Mid-Nyland Vocational College, signs a receipt for his driving licence at Vallgård Police Station.

At home in the flat in Svenska Gården in Munkshöjden: the very next evening Jacke sneaks his hand down into his father’s, typesetter K-G. Pettersson’s, overcoat pocket. It is getting on for 9 o’clock and KG is sitting deeply submerged in his favourite armchair, staring concentratedly at the premiere of a new show.

Six out of forty

make it every week

sings a bright girl’s voice.

Then: the Official Supervisors and their solemn ‘Good evening’. And then: the blonde girl in her mini-dress and high boots, the glass holder with its plastic balls, the plastic balls with numbers on. More…

Suburban dreams

30 March 2004 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Kahden ja yhden yön tarinoita (‘Tales from two and one nights’, Sammakko, 2003)

Reponen, Tane, Aleksi and Little Juha; once we all climbed up the path to the old dump with bows on our backs, our arrows sticking out from the tops of our boots. It was April. In the field above the dump puddles reflected the opaque sky, where we were going to shoot our arrows.

The field was the highest point in our neighbourhood. We could see the shopping centre, the library and the sawdust running track through the school woods. We could see the high-rise flats on Tora-alhontie road and the huts in the allotments. We could make out the thick spruce forest of Sovinnonvuori along the greenish grey coastline at Kapeasalmi. Our homes sat there below us. Softly droning cranes, yellow totem animals of hope, swung back and forth above the unfinished houses. In the distance was the centre of town with all its churches and scars. Here everything was just beginning. The swaggering confidence of ten-year-old boys was straining within us and would carry us far like Geronimo’s bow. More…

Really existing?

30 March 2007 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Mehiläispaviljonki. Kertomus parvista (‘The Bee Pavilion. A story about swarms’, Teos, 2006)

There are few old buildings in this town. Most are demolished to make way for new ones long before they reach the end of their first century.

Nevertheless, one brick building in our part of town, built at the beginning of the last century, was spared demolition for a long time. The two-storey building functioned as a Support Centre for the Psychically Ill and later on, for a couple of winters, as a shelter for alcoholics. The board fence that had surrounded the building for decades was taken down long before the building itself, but the maples on the sidewalk cast their shadows on its windows to the very end. When the lilacs and dogwoods in the back garden were in bloom, their heavy racemes shed purple and white on the sand. More…

The net

30 June 2000 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Verkko (‘The net’, WSOY, 1999). Introduction by Peter Mickwitz

The descent

Down the stairs, out through the gate into the street

and you wonder

what the cobblestones had in mind

with the waves that beat

and the rock that was humbled

smooth in the course of millennia.

Streetcars would rumble

toward them with ancient god force.

Now the stones lie there quietly like

fish blown ashore

petrified by the sun.

Their memory is short. Steel is mute.

The rails remember Kallio, remember Töölö.

Words are thinner than they used to be;

they’ve been walked over too many times.

The city. more glabrous, no longer stretches

algae-covered tentacles to the gates of Babylon.

Like an animal with a premonition, the city pulls its soft parts

inside a calcareous shell, does its work there in secret.

Much has disappeared: no more twitching tectonic plates

brought on by words, no electric storms in the bowels.

Coffee is the measure of violence: no more tobacco

in whose smoke one could heal loneliness and the world.

As before, you look through glass, just a thin glass,

at the sidewalk and trees facing the restaurant. A man

is pushing a baby carriage. The glass reflects your face very briefly.

Part of you is out there, part stumbles about again in some Yoldia

a mute stone and a worn hope in his pocket. still,

that the world’s mute stones would break down into song, give

voice, crumble a couple of notes here, and a key.

Vermeer: the kitchen maid

A great painting does not require a great subject,

kings in pantyhose, the Peace of Westphalia.

The kitchen maid pours milk in a bowl, and soon

the canvas brims with self-radiant liquid

in which the morning and chunks of bread float.

The trap is primed. No rat to be seen.

Bits of something white roll on the floor. Smelling salts?

Under the milky film of the wall there are things

going on that the maid has no inkling of

a cockroach makes its way through the sawdust,

enzymes dismantle compounds into smaller pieces.

Farther away, a star collapses

and begins to radiate darkness.

Its message – a quantum of black light –

reaches Helsinki only today,

a city surrounded by ramparts of snow.

These, among other things, influence

my being what I am.

I wrap myself in darkness and wait

for the next whim, a tiny,

decisive mistake.

That’s why

The half-drowned

apartment building drifts.

Between the stuccoed ribs

disease blooms, sprouts tendrils.

punctures pulmonar alveoli. articular capsules.

Every night I could melt into the tub

until the water darkens to a hepatic dream.

One must protect oneself against the outside air.

The light draws boundaries that are too clear.

One must protect oneself against the brightness of skin.

That is why I travel deeper into your chest,

crave the tar from your lungs and the tracheae

into which I blow, a fanfare, when we are

heat and hunger,

grow vertically up from the ground toward

the fainted sun,

pull up rails, roots, traffic signs,

rusty legends,

rear up to the height of our withers, slop sweat and oil.

Aerial view

These wondrous mobiles

with which we can conquer distances.

Only the view always is the same heavenly

snow drift, nothing but condensing steam.

Icarus must have cooled his wings here,

the wax whose precise consistency is a mystery to us.

The higher he rose

the worse he froze

until the wax became too cold and melted.

By scientific means machines have been built

in which a human being can rise and fly to another

planetary phenomena in his belly

such as the direction of blood’s circulation. Loneliness

has rarely been a castle in whose cellar

philosophy was tinkered with or music distilled.

The horses were harnessed for death, the rest into museums,

cast in plastic.

The polar sea folds into a pocket

as a map that tells you where you should already

be, and how.

Translated by Anselm Hollo

Across Europe

30 June 1990 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Mika Waltari (1908–1979) was a prolific writer, journalist and translator. In addition to historical novels, he wrote short stories, travel books, thrillers, plays, books for children, film scripts and poetry. The newly independent Finland of the 1920s, as it emerged from a traumatic period of civil war, declared that its windows were open to Europe, and Waltari’s first novel Suuri illusioni (‘The great illusion’), written in Paris when he was only 19, represents urban romanticism and the world of European capitals.The optimism and enthusiasm for modern life of the 1920s are strongly present in Waltari’s travelogue, Yksinäisen miehen juna, (‘Lonely man’s train’; 1929), an account, both ironic and engagingly naïve, of a great adventure in Europe after the post-1918 redrawing of the continent’s map. The book’s motto is a phrase from Paul Morand, a writer Waltari admired: ‘How is it possible to remain stationary when time slips like ice through our hot hands.’ This work of Waltari’s youth has never before been translated. The author travels by ship and train as far as Turkey; in the following extract, he has reached Hungary

Yksinäisen miehen juna (‘Lonely Man’s train’)

How adorable express trains are – the mighty engines, the rhythm of the rails, the sway of the carriages, the flashing-by of the milestones, the gravel embankments contracting into speeding lines. A train is the only place you can be completely at ease, free from heartache, free from longing, free from tormenting thoughts. Whenever I die, I hope it will be on a train flashing towards some unknown town at eighty miles an hour, with mountains looming on the horizon, and the points lighting up in the descending dusk…. More…

Letters to Trinidad

31 March 1990 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Kirjeitä Trinidadiin (‘Letters to Trinidad’, 1989). Introduction by Suvi Ahola

Elisabet suggested that they should go to the beach. Seppo would have liked to show her the coral, but his wife thought it was too far, and so they decided to go to the beach nearest the hotel.

They hired mattresses and a sun umbrella and found places in the first row, close to the water. The sea glittered, and long, shallow waves rolled towards the sand, like long, even snores. Seppo dozed for a moment, then sat up and, taking his binoculars, focused out to sea. Two warships sailed eastwards through the glittering waves. Egypt, Jordan and the Arab countries all around, Iran and Iraq close by, Libya not far away – it was like lying on a keg of gunpowder!

Elisabet went swimming, and he followed. He carried his wife through the waves, played the life-saver and dragged Elisabet’s apparently lifeless body through the waves. They dived, and Elizabet complained that the salt stung her eyes. They lay on their mattresses and when Seppo glanced at her, he felt again the sharp stab of desire, and would have liked to make love, but had to content himself with caressing her thigh. When his desire became too great he covered himself with a rowel, and Elisabet laughed.

‘Again? You’re insatiable’, she said. More…

Images of isolation

31 March 1992 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems by Helvi Juvonen, commentary by Soila Lehtonen

Little is known of the circumstances of Helvi Juvonen’s life. Her fame rests on five collections of poetry – mixing humility and celebration with an uncompromising rigour – published in the ten years before her death at the age of 40 (a sixth appeared posthumously). Her existence, in the drab surroundings of post-war Helsinki, was modest: after studies at Helsinki University, and posts as a bank clerk and proof-reader, she lived by writing and translation, including some brilliant renderings into Finnish of the poems of the 19th-century American poet Emily Dickinson.

Helvi Juvonen’s universe is crowded with ostensibly insignificant phenomena: her eye discerns a mole, lichen, dwarf-trees, a shrew; she studies tones of stone and moss; she ‘doesn’t often dare to look at the clouds’.

Us

Rocks, forgotten within themselves,

have grown dear to me.

The trees’ singing, so useless,

is my friend.

Silver lichen,

brother in beggary,

please don’t hate my shadow

on the streaked rock. More…

Kidult culture

4 April 2012 | Non-fiction, Tales of a journalist

Illustration: Joonas Väänänen

Life is hard, and then you grow up. Except that you don’t really, at least if you keep watching television. Jyrki Lehtola takes a look at entertainment for the Peter Pan generation – which, he argues, is pretty much all of us

When did we start making television for children? I mean, in theory for adults (believe me, advertises, believe me: for adults!) but in practice for children?

Theoretically television is a wonderful, flexible medium less dependent on big money than the film business. Why did we let it slip out of our hands as a form of expression?

Why did we start making adult programmes for children and children’s programmes for adults? In other words, why do we make exactly the same TV programmes for everyone? More…

The lake

30 June 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Järvi (‘The lake’), a short story, 1915. Introductions by Kai Laitinen and Pekka Tarkka

I travel the world, not out of any desire for adventure, but because that is the way things have happened. The best of my wanderings are in obscure, tucked-away regions, where life is humdrum and pitched in a low key. There I have no need to stave off nostalgia for the past by leading a hectic life: my days go by in stolid succession from season to season, I am an ordinary unimportant individual among all the rest. For long stretches of time my life does not strike me as being either dull or bright; I derive a certain satisfaction from its very emptiness. It is as though I were, by degrees and to the best of my ability, paying off a kind of debt. More…

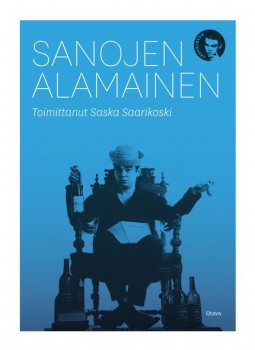

The poet and translator Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) was a legend in his own lifetime, a media darling, a public drinker who had five children with four women. His oeuvre nevertheless encompasses 30 works, and his translations include Homer and James Joyce. The journalist Saska Saarikoski (born 1963) has finally read all that work – in search of the father whom he seldom met. The following samples are from his annotated selection of Pentti Saarikoski’s thoughts over 30 years, Sanojen alamainen (‘Servant of words’, Otava, 2012; see

The poet and translator Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) was a legend in his own lifetime, a media darling, a public drinker who had five children with four women. His oeuvre nevertheless encompasses 30 works, and his translations include Homer and James Joyce. The journalist Saska Saarikoski (born 1963) has finally read all that work – in search of the father whom he seldom met. The following samples are from his annotated selection of Pentti Saarikoski’s thoughts over 30 years, Sanojen alamainen (‘Servant of words’, Otava, 2012; see