Search results for "2011/04/2010/05/song-without-words"

Everyday life at the Science Forum 2011

20 January 2011 | In the news

‘Everyday life’ in focus: scientific approaches. Picture: Elina Warsta

This year’s Science Forum took place in Helsinki between 12 and 16 January. This biennial science festival – which has existed in its current format since 1977 – invites a wide audience to lectures, debates, discussions and various other events where scholars introduce their branch of research and science. This time the theme was ‘Science and everyday life’.

The Science Forum is organised by the Federation of Finnish Learned Societies, the Finnish Academies of Sciences and Letters and the Finnish Cultural Foundation.

In Finnish, the word for ‘everyday life’ is arki. Professor of Consumer Economics Visa Heinonen defined arki as follows: ‘Scientifically arki cannot be defined undisputably. An individual experiences the everyday as a ‘stream’ of life. Arki is mostly the recurrence of the small basic elements of life and the constant renewal of the prerequisites of existence. The everyday contains much that is routine as well as small moments of joy. Carpe diem, seize the moment, might be a good guideline to life.’

Among the Forum’s topics were the everyday work of scientific research and its significance for the development of everyday life in society, dimensions of consumer culture, multicultural society, religion, the arts and the media, technological advances in food production and the built environment, future energy sources and the global economy.

The Science Forum attracted 18,000 visitors, in addition to the 3,000 who participated in the Forum via the Internet. The five most popular topics, or sessions, were those entitled ‘Good life’, ‘Ageing as a biological phenomenon’, ‘Nanotechnology changing everyday life’, ‘Sleep – a third of life’ and ‘Food and everyday chemistry’.

Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2011

24 November 2011 | In the news

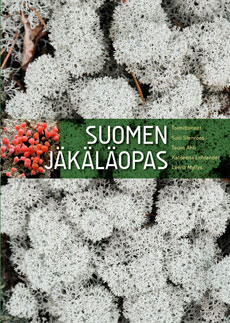

‘Scientific, aesthetic, timely: the work is all of these. A work of non-fiction can be both precisely factual and emotional, full of both information and soul. A good non-fiction book will surprise. I did not expect to be enthused by lichens, their variety and colours,’ declared Professor Alf Reen in announcing the winner of this year’s Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction on 17 November.

‘Scientific, aesthetic, timely: the work is all of these. A work of non-fiction can be both precisely factual and emotional, full of both information and soul. A good non-fiction book will surprise. I did not expect to be enthused by lichens, their variety and colours,’ declared Professor Alf Reen in announcing the winner of this year’s Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction on 17 November.

The winning work is Suomen jäkäläopas (‘Guidebook of lichens in Finland’), edited by Soili Stenroos & Teuvo Ahti & Katileena Lohtander & Leena Myllys (The Botanical Museum / The Finnish Museum of Natural History). The prize is worth €30,000.

The other works on the shortlist of six were the following: Kustaa III ja suuri merisota. Taistelut Suomenlahdella 1788–1790 [(‘Gustav III and the great sea war. Battles in the Gulf of Finland 1788–1790’, John Nurminen Foundation), written by Raoul Johnsson, with an editorial board consisting of Maria Grönroos & Ilkka Karttunen &Tommi Jokivaara & Juhani Kaskeala & Erik Båsk; Unihiekkaa etsimässä. Ratkaisuja vauvan ja taaperon unipulmiin (‘In search of the sandman. Solutions to babies’ and toddlers’ sleep problems’ ) by Anna Keski-Rahkonen & Minna Nalbantoglu (Duodecim); Operaatio Hokki. Päämajan vaiettu kaukopartio (‘Operation Hokki. Headquarters’ silenced long-distance patrol’), an account of a long-distance patrol strike in eastern Karelia during the Continuation War in 1944, by Mikko Porvali (Atena); Trotski (‘Trotsky’, Gummerus; biography) by Christer Pursiainen; and Lintukuvauksen käsikirja (‘Handbook of bird photography’) by Markus Varesvuo & Jari Peltomäki & Bence Máté (Docendo).

Turku, city of culture 2011

21 January 2011 | In the news

Passing the peace: citizens of Turku gathering to listen to the traditional declaration of peace at Christmas in front of the Cathedral. Photo: Esko Keski-oja

Since 1985, cities in the countries of the European Union have been chosen as European Capitals of Culture each year. More than 40 cities have been designated so far; a city is not chosen only for what it is but, more importantly, what it plans to do for year and also for what will remain after the year is over – the intention is that citizens and the local culture should profit from the investments made.

This year the two cities are Tallinn in Estonia and Turku, the oldest city and briefly (1809–1812) the capital of what was then the Grand Duchy of Finland, on the coast, 160 kilometres west of Helsinki. The pair will also co-operate in making this year a special one in their cultural lives.

The city of Turku declared its Cultural Capital year open on 15 January with a massive firework display glittering over the River Aura. This cultural capital enterprise, with a budget of 50 million euros and an ambitious programme will, hopefully, involve two million participants in the five thousand cultural events and occasions.

The books that sold

11 March 2011 | In the news

-Today we're off to the Middle Ages Fair. – Oh, right. - Welcome! I'm Knight Orgulf. – I'm a noblewoman. -Who are you? – The plague. *From Fingerpori by Pertti Jarla

Among the ten best-selling Finnish fiction books in 2010, according statistics compiled by the Booksellers’ Association of Finland, were three crime novels.

Number one on the list was the latest thriller by Ilkka Remes, Shokkiaalto (‘Shock wave‘, WSOY). It sold 72,600 copies. Second came a new family novel Totta (‘True’, Otava) by Riikka Pulkkinen, 59,100 copies.

Number three was a new thriller by Reijo Mäki (Kolmijalkainen mies, ‘The three-legged man’, Otava), and a new police novel by Matti Yrjänä Joensuu, Harjunpää ja rautahuone (‘Harjunpää and the iron room’, Otava), was number six.

The Finlandia Fiction Prize winner 2010, Nenäpäivä (‘Nose day’, Teos) by Mikko Rimminen, sold almost 54,000 copies and was fourth on the list. Sofi Oksanen’s record-breaking, prize-winning Puhdistus (Purge, WSOY; first published in 2008) was still in fifth place, with 52,000 copies sold.

Among translated fiction books were, as usual, names like Patricia Cornwell, Dan Brown and Liza Marklund.

In non-fiction, the weather, fickle and fierce, seems to be a subject of endless interest to Finns; the list was topped by Sääpäiväkirja 2011 (‘Weather book 2011’, Otava), with a whopping 140,000 copies. Number two was the Guinness World Records 2011, but with just 43,000 copies. Books on wine, cookery and garden were popular. A book on Finnish history after the civil war, Vihan ja rakkauden liekit (‘Flames of hate and love’, Otava) by Sirpa Kähkönen, made it to number 8 on the list.

The Finnish children’s books best-sellers’ list was topped by the latest picture book by Mauri Kunnas, Hurja-Harri ja pullon henki (‘Wild Harry and the genie’, Otava), selling almost 66,000 copies. As usual, Walt Disney ruled the roost in the translated fiction list.

The Finnish comics list was dominated by Pertti Jarla (his Fingerpori series books sold more than 70,000 copies, almost as much as Remes’ Shokkiaalto!) and Juba Tuomola (Viivi and Wagner series; both mostly published by Arktinen Banaani): between them, they grabbed 14 places out of 20!

Solid, intangible

26 September 2013 | Fiction, poetry

Poems from Mot natten. Dikter 2010 (‘Towards the night. Poems 2010’, Schildts & Söderströms, 2013). Introduction by Michel Ekman

Memory

If you give me time

I don’t weigh it in my hand:

it’s so light, so transparent

and heavy as the thick

shining darkness

in the backyard gateway

to memory

How to peel an orange

30 December 2002 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Auringon asema (‘The position of the sun’, Otava, 2002)

There are times when God rules. Then logic is burned on bonfires and left to rot in damp prisons with rats. There are times when logic rules. Then God is burned in the squares and his houses are made into schools. There are times when attempts are made to demonstrate that God and logic can live in the same place and that they are, in fact, the same thing, but those times are truly strange times. And there are times when God and logic live side by side but in different places, like adult siblings who cannot live in the same place but nevertheless get on well together. When my father and my mother loved each other, they were ruled by God, and there was no logic in it, none at all. More…

The way to heaven

30 June 1996 | Archives online, Fiction

Extracts from the novel Pyhiesi yhteyteen (‘Numbered among your saints’, WSOY, 1995). Interview with Jari Tervo by Jari Tervo

The wind sighs. The sound comes about when a cloud drives through a tree. I hear birds, as a young girl I could identify the species from the song; now I can no longer see them properly, and hear only distant song. Whether sparrow, titmouse or lark. Exact names, too, tend to disappear. Sometimes, in the old people’s home, I find myself staring at my food, what it is served on, and can’t get the name into my head. The sun came to my grandson’s funeral. It rose from the grave into which my little Marzipan will be lowered. I don’t remember what the weather did when my husband was buried.

A plate. Food is served on a plate. There are deep plates and shallow plates; soups are ladled into the deep ones. More…

Finlandia Junior Prize 2010

26 November 2010 | In the news

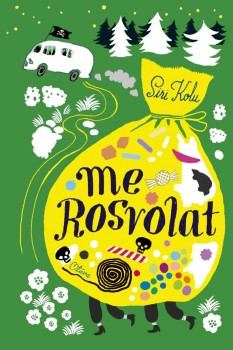

The Finlandia Junior Prize has gone to author Siri Kolu and illustrator Tuuli Juusela for the novel Me Rosvolat (‘Me and the Robbersons’, Otava); they will share the award of €30,000 (see the Prize jury assessments of the shortlist here). The winner was chosen by actor and writer Hannu-Pekka Björkman.

The Finlandia Junior Prize has gone to author Siri Kolu and illustrator Tuuli Juusela for the novel Me Rosvolat (‘Me and the Robbersons’, Otava); they will share the award of €30,000 (see the Prize jury assessments of the shortlist here). The winner was chosen by actor and writer Hannu-Pekka Björkman.

Awarding the prize on 25 November he said: ‘It caught my attention that in none of the six shortlisted children’s books are there any so-called nuclear families, at least not for long. The main characters constantly live and grow without something – the lack of parents or the attention of an adult is a serious matter to a child. However, in these books there is always someone who cares, not perhaps a stereotypical mom or dad, but an adult nevertheless.’ In Björkman’s opinion Me Rosvolat, with its rich language and a whiff of anarchy, presents the reader with moments of realisation and wonderment.

The last melody

30 September 1995 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Kadotettu puutarha (‘The lost garden’, WSOY, 1995). Introduction by Riina Katajavuori

Their sojourn at the villa extended into the autumn of 1944; the schools did not go back as usual on the first of September. Repair of the university buildings progressed rapidly; the work had begun immediately after the bombing. The Doctor went to town from time to time, but nothing bound the family to it, and he returned to his desk in the attic room and to his solitary walks by the lake. His heart troubled him from time to time. It did not like these walks, did not like exertion; but he had succeeded in concealing the matter from Elisabet. After one particular attack, he had secretly seen a doctor in town, and now, instead of camphor tablets, he always had those little buttons in his pocket, the breast pocket of his waistcoat. He swallowed one from time to time on these expeditions, a pain in his wrists and his eyes staring dimly at a clump of ferns that seemed to have become hazy, or a tree-top that seemed to be falling toward him. He did not wish Elisabet to know. Not this, in Elisabet’s world, not this, in air that was suffused with grief for their dead son Leo, with well controlled and beautifully expressed emotion, with concern for the remaining boy, who was there, on the frontier, with the burdensome and universal tragedy that filled the air as light filled it in daytime. More…

Briefcase man

31 December 2000 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Aura (Otava, 2000). Introduction by Mervi Kantokorpi

He was born in the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland the year the world caught fire. He learned to read the year of the revolution, and spoke two languages as his mother tongue border – language and enemy language, as he often used to say. He was proud of only one of his languages; the other, he loved secretly. He spoke one loudly, the other softly, almost in a whisper.

At night, on the telephone, he spoke far away – you could see it, even in the dark, from his expression, his half-closed eyes sometimes breaking into song. It was so beautiful and soft that I wept under the blankets and hated myself because of the effect that language had on me.

Stinking tinker Karelian trickster Russian drinker, little Russky’s dancing in a leather skirt, skirt tears and oh! little Russky’s hurt.

Count to ten, he said. But count in Finnish. Or Swedish, that’ll baffle them. And if they call you a Swedish bastard, it’s not so bad. I’ve taught you the numbers in Arabic and Spanish, too, but I don’t think you’ll be able to remember them yet. More…

The strike

13 December 1980 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Täällä Pohjantähden alla (‘Here beneath the North Star’), chapter 3, volume II. Introduction by Juhani Niemi

With banners held aloft, the procession of strikers moved towards the Manor. It was known that the strikebreakers had arrived early and that the district constable was with them. Just before reaching the field the marchers struck up a song, and they went on singing after they had halted at the edge of the field. The men at work in the field went on with their tasks, casting occasional furtive glances at the strikers. Nearest to the road stood the Baron and the constable. Uolevi Yllö’s head was bandaged: someone had attacked him with a bicycle chain as he left the field at dusk the evening before. Arvo Töyry was in the field too, the landowners having agreed that those who had got their own harrowing and sowing done should lend the others a hand. Not all the men in the field were known to the strikers. The son of the district doctor was there they noticed, and the sons of several of the village gentry, as well as the men from the smallholdings. More…

It takes a life to say

31 December 2007 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems, published in You go the words (Action Books, Scandinavian Series, Indiana, 2007). Introduction by Trygve Söderling

|

We go and search it is not words * You go the * And spread out To only * The song * One time I have a name * a longing * A morning’s * Words are words But word’s image Alas stay not * Fly out, my day

fly, fly day to meet

fly, fly, you the wretched's

their, everyone's

in all times

peace and day

on ground's floor

floor ground

o you

in man's name

* Suneveningspring * Dog bolts happy * And to not speak more it takes a life to say but – as the everyday moment O no beauty But your light – a smile what and to know * And allthesame The white day * |

Vi går och söker det är ej ord * Du går de * Och bredd ut Att endast * Sången * En gång Jag har ett namn * en längtan * En morgons * Ord är ord Men ords bild Ack stanna ej * Flyg ut, min dag

flyg, flyg dag till möte

flyg, flyg, du de armas

deras, allas

i alla tider

lugn och dag

på marks golv

golv mark

o du

i människans namn

* Solaftonvår * Hund skenar glad * Och att ej tala mer det tar ett liv att säga men – som vardagens stund O ingen skönhet Men ditt ljus – ett leende vad och att veta * Och alltjämt Den vita dag * |

Translated by Fredrik Hertzberg

Speaking with silence

26 September 2013 | Reviews

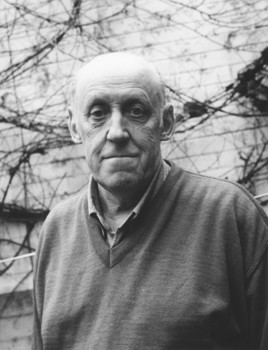

Bo Carpelan. Photo: Charlotta Boucht / Schildts & Söderströms

Bo Carpelan

Mot natten

[Towards the night. Poems 2010]

Helsinki: Schildts & Söderströms, 2013. 69 p.

ISBN 978-951-52-32-20-5

€21, paperback

‘Don’t change, grow deeper ,’ wrote Bo Carpelan: over the years he broadened his poetic range and his personal idiom evolved, but it happened organically, without sudden upheavals of style or idea.

Mot natten (‘Towards the night’) is Carpelan’s last collection of poems. This is underlined by the book’s subtitle, Poems 2010. By then Carpelan (1926–2011) was already marked by the illness that took his life in early 2011. It doesn’t show in the quality of the poems, but knowing it may make it harder for the reader to approach them with unclouded eyes. When a great poet concludes his work one wants to seek a synthesis or a concluding message, and that may encumber one’s reading. So is there such a message? In some ways there is, but Carpelan was not a man of pointed formulations. His ideals emerged without much fuss. More…

Why translate?

28 January 2015 | Essays, Non-fiction

Down by the sea: Herbert Lomas in Aldeburgh. – Photo: Soila Lehtonen

‘People do not read translations to encourage minor literatures but to rediscover themselves in new imaginative adventures‚’ says the poet and translator Herbert Lomas in this essay on translation (first published in Books from Finland 1/1982). ‘Translation is a thankless activity,’ he concludes – and yet ‘you have the pleasure of writing without the agony of primary invention. It’s like reading, only more so. It’s like writing, only less so.’ And how do Finnish and English differ from each other, actually?

Any writer’s likely to feel – unless he’s a star, a celebrity, a very popular and different beast – that the writer is a necessary evil in the publisher’s world, but not very necessary. How much more, then, the translator from a ‘small’ country’s language.

Why do it? The pay’s absurd, you need the time for your own writing, it’s very hard to please people, and translation is, after all, the complacent argument goes, impossible. I’m convinced by all these arguments, and really I can’t afford to go on; but I don’t regret what I’ve done and, looking back, I can find two reasons for translating Finnish writing, one personal, the other cultural. More…