Search results for "2011/04/2010/10/riikka-pulkkinen-totta-true"

Tiger in the grass

31 March 2001 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Maan ääreen (‘To the end of the earth’, Otava, 1999)

I left Kronstadt at the end of October in the year 1868, when I was 22 years old.

The Mozart was a three-hundred-ton barque. Even on the journey to Tvedestrand in Norway I vomited yellow bile and my toes and fingers froze. We lingered in Tvedestrand for three months while the vessel was repaired in dock. To amuse myself, I drew and wrote an accurate description of the ship. That work ended up in the sea. From the harbour captain’s library I borrowed German books which dealt with geology and topology. Their reality was different from that of the law and the interpretation of its letter and spirit. When a topologist draws a map, it has to be true. Otherwise travellers will get lost, I thought childishly, as if it were possible to draw a line between true and true. More…

The miracle of the rose

30 June 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Naurava neitsyt (‘The laughing virgin’, WSOY, 1996). The narrator in this first novel by Irja Rane is an elderly headmaster and clergyman in 1930s Germany. In his letters to his son, Mr Klein contemplates the present state of the world, hardly recovered from the previous war, his own incapacity for true intimacy – and tells his son the story of the laughing virgin, a legend he saw come alive. Naurava neitsyt won the Finlandia Prize for Fiction in 1996

28 August

My dear boy,

I received your letter yesterday at dinner. Let me just say that I was delighted to see it! For as I went to table I was not in the conciliatory frame of mind that is suitable in sitting down to enjoy the gifts of God. I was still fretting when Mademoiselle put her head through the serving hatch and said:

‘There is a letter for you, sir.’

‘Have I not said that I must not be disturbed,’ I growled. I was surprised myself at the abruptness of my voice.

‘By your leave, it is from Berlin,’ said Mademoiselle. ‘Perhaps it is from the young gentleman.’

‘Bring it here,’ I said. More…

Johanna Korhonen: Kymmenen polkua populismiin [Ten paths to populism]

3 October 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kymmenen polkua populismiin. Kuinka vaikenevasta Suomesta tuli äänekkään populismin pelikenttä

Kymmenen polkua populismiin. Kuinka vaikenevasta Suomesta tuli äänekkään populismin pelikenttä

[Ten paths to populism. How silent Finland became a playing field for loud populism]

Helsinki: Into Kustannus Oy, 2013. 81p.

ISBN 951-952-264-257-8

€15, paperback

This pamphlet on the populist True Finns party was commissioned by the British think tank Counterpoint (PDF available in Finnish). In 2011, under the leadership of the rhetorically gifted Timo Soini, the True Finns became the largest opposition party in the Finnish parliament. In the background of this phenomenon the journalist Johanna Korhonen sees, among other things, the recession of the 1990s, the fear of economic insecurity, and the paucity of alternatives and debate that characterise politics in Finland. The left-leaning party favours simplifications and longs for national unity and security. It nevertheless includes an extremist nationalist minority whose agenda includes resistance to the European Union, cultural diversity, minority rights and foreign influences, and can even be racist. Korhonen focuses and simplifies in pamphleteering fashion, but argues patiently, basing her views on facts, and considers the beneficial effects the populist party has had on the national debate, offering her suggestions for a more humane politics.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Helene Schjerfbeck. Och jag målar ändå [Helene Schjerfbeck. And I still paint]

16 December 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Helene Schjerfbeck. Och jag målar ändå. Brev till Maria Wiik 1907–1928

Helene Schjerfbeck. Och jag målar ändå. Brev till Maria Wiik 1907–1928

[Helene Schjerfbeck. And I still paint. Letters to Maria Wiik 1907–1928]

Utgivna av [Edited by]: Lena Holger

Helsingfors: Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland; Stockholm: Bokförlaget Atlantis, 2011. 301 p., ill.

ISBN (Finland) 978-951-583-233-7

ISBN (Sweden) 978-91-7353-524-3

€ 44, hardback

In Finnish:

Helene Schjerfbeck. Silti minä maalaan. Taiteilijan kirjeitä

[Helene Schjerfbeck. And I still paint. Letters from the artist]

Toimittanut [Edited by]: Lena Holger

Suomennos [Translated by]: Laura Jänisniemi

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2011. 300 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-305-0

€ 44, hardback

This work contains a half of the collection of some 200 letters (owned by the Signe and Ane Gyllenberg’s foundation), until now unpublished, from artist Helene Schjerfbeck (1862–1946) to her artist friend Maria Wiik (1853–1928), dating from 1907 to 1928. They are selected and commented by the Swedish art historian Lena Holger. Schjerfbeck lived most of her life with her mother in two small towns, Hyvinge (in Finnish, Hyvinge) and Ekenäs (Tammisaari), from 1902 to 1938, mainly poor and often ill. In her youth Schjerfbeck was able to travel in Europe, but after moving to Hyvinge it took her 15 years to visit Helsinki again. In these letters she writes vividly about art and her painting, as well as about her isolated everyday life. Despite often very difficult circumstances, she never gave up her ambitions and high standards. Her brilliant, amazing, extensive series of self-portraits are today among the most sought-after north European paintings; she herself stayed mostly poor all her long life. The book is richly illustrated with Schjerfbeck’s paintings (mainly from the period), drawings and photographs.

Juhani Koivisto: Suurten tunteiden talo. Kohtauksia Kansallisoopperan vuosisadalta [The house of great emotions. Scenes from a century of the Finnish National Opera]

30 June 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Suurten tunteiden talo. Kohtauksia Kansallisoopperan vuosisadalta

Suurten tunteiden talo. Kohtauksia Kansallisoopperan vuosisadalta

[The house of great emotions. Scenes from a century of the Finnish National Opera]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2011. 229 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-0-37667-6

€ 45, paperback

2011 marks the one-hundredth anniversary of the founding of the Finnish National Opera. This richly illustrated and entertaining book describes events that have been absent from previous ‘official’ historical accounts. Readers will encounter over a hundred opera denizens who have made audiences – and, according to many anecdotes, each other – laugh and cry. The initial stages of the opera and ballet were modest in scope when viewed from outside, but the trailblazers involved were tremendous talents and personalities. The brighest star was the singer Aino Ackté, who enjoyed an international reputation. Gossip about intrigues and artistic differences at the opera house over the decades is confirmed in candid interviews with performers. The content of the book is based on archival sources, letters, memoirs, interviews and stories told inside the opera house. Juhani Koivisto, the Opera’s chief dramaturge, clearly has an excellent inside knowledge of his subject. Translated by Ruth Urbom

Hare-raising

13 February 2015 | Reviews

In this job, it’s a heart-lifting moment when you spot a new Finnish novel diplayed in prime position on a London bookshop table – and we’ve seen Tuomas Kyrö’s The Beggar & The Hare in not just one bookshop, but many. Popular among booksellers, then – and we’re guessing, readers – the book nevertheless seems in general to have remained beneath the radar of the critics and can therefore be termed a real word-of-mouth success. Kyrö (born 1974), a writer and cartoonist, is the author of the wildly popular Mielensäpahoittaja (‘Taking umbridge’) novels, about an 80-year-old curmudgeon who grumbles about practically everything. His new book – a story about a man and his rabbit, a satire of contemporary Finland – seems to found a warm welcome in Britain. Stephen Chan dissects its charm

Tuomas Kyrö: The Beggar & The Hare

Tuomas Kyrö: The Beggar & The Hare

(translated by David McDuff. London: Short Books, 2011)

Kerjäläinen ja jänis (Helsinki: Siltala, 2011)

For someone who is not Finnish, but who has had a love affair with the country – not its beauties but its idiosyncratic masochisms; its melancholia and its perpetual silences; its concocted mythologies and histories; its one great composer, Sibelius, and its one great architect, Aalto; and the fact that Sibelius’s Finlandia, written for a country of snow and frozen lakes, should become the national anthem of the doomed state of Biafra, with thousands of doomed soldiers marching to its strains under the African sun – this book and its idiots and idiocies seemed to sum up everything about a country that can be profoundly moving, and profoundly stupid.

It’s an idiot book; its closest cousin is Voltaire’s Candide (1759). But, whereas Candide was both a comedic satire and a critique of the German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), The Beggar & The Hare is merely an insider’s self-satire. Someone who has not spent time in Finland would have no idea how to imagine the events of this book. Candide, too, deployed a foil for its eponymous hero, and that was Pangloss, the philosopher Leibniz himself in thin disguise. Together they traverse alien geographies and cultures, each given dimension by the other. More…

Annika Luther: De hemlösas stad [The city of the homeless]

17 January 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

De hemlösas stad

De hemlösas stad

[The city of the homeless]

Helsingfors: Söderströms, 2011. 237 p.

ISBN 978-951-522-846-8

€ 21.10, paperback

Kodittomien kaupunki

Suomennos [Translation from Swedish into Finnish]: Asko Sahlberg

Helsinki: Teos, 2011. 240 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-404-9

€ 33.10, paperback

Annika Luther’s novel is an example of the popular genre of dystopia. Its ecocritical overtones prompt radically new ways of thinking about the effects of climate change. In 2050, the bulk of the earth’s surface is under water, and people from various corners of the earth have been evacuated to Finland. The majority of the residents in Helsinki are Indian and Chinese. Finns are in the minority, and most of them are hopelessly addicted to alcohol. Fifteen-year-old Lilja lives in the city of Jyväskylä with her family, in a protected and tightly controlled neighbourhood. She becomes interested in her family history and decides to find out about her aunt, a marine biologist who remained in flooded Helsinki. Gradually, the mysteries of the past open up to her. The novel is about survival and adaptation. Luther is an original writer, uncompromising in her ethical stance. As in her previous novel, Ivoria (2009), she describes Helsinki with affection: despite the ruined landscape, the city maintains its proud bearing.

Translated by Fleur Jeremiah and Emily Jeremiah

Sanna Tahvanainen & Sari Airola: Silva och teservicen som fick fötter [Silva and the tea set that took to its feet]

13 January 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Silva och teservicen som fick fötter

Silva och teservicen som fick fötter

[Silva and the tea set that took to its feet]

Kuvitus [Ill. by]: Sari Airola

Helsingfors: Schildts, 2011. 32 p.

ISBN 78-951-50-2053-6

€ 21.20, hardback

Silva ja teeastiasto joka sai jalat alleen

Suomennos [Translation from Swedish into Finnish]: Jyrki Kiiskinen

Helsinki: Schildts, 2011. 32 p.

ISBN 978-951-50-2054-3

€ 21.20, hardback

Sari Airola’s ability to depict different emotions makes her one of the most interesting Finnish illustrators of children’s books. Airola has long lived in Hong Kong and one can often sense an oriental spirit in her work. In this book, she makes use of Asian textile printing plates to enliven the surfaces of the images. The subject of this debut children’s book by Tahvanainen (born 1975), who is also a poet and novelist, evokes empathy with family situations that deviate from the norm. Silva lives in a big house with her mother, an isolated control freak and migraine sufferer. When her mother suffers an episode, Silva is unable to establish any contact with her and feels insecure. Although the text is allegorical, the book’s message, which concerns a parent’s caring responsibilities and a child’s need to be loved, remains accessible to children. Once the migraine attack is over, the mother goes out to look for Silva; mother and daughter are reconciled when Silva, at last, puts her fears into words.

Translated by Fleur Jeremiah and Emily Jeremiah

Marja-Leena Tiainen: Kahden maailman tyttö [The girl from two worlds]

18 January 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kahden maailman tyttö

Kahden maailman tyttö

[The girl from two worlds]

Helsinki: Tammi, 2011. 261 p.

ISBN 978-951-31-5937-5

€ 26.65, hardback

Marja-Leena Tiainen (born 1951) has dealt with unemployment, immigration, and racism in her works, in ways that are accessible to her young readership. She researches her topics with care. The idea for this book dates back to 2004, when the author made the acquaintance of a Muslim girl who lived in a reception centre in eastern Finland; her experiences fed into Tara’s story. Tiainen’s central theme, ‘honour’ violence in the Muslim community, is surprisingly similar to Jari Tervo’s Layla (WSOY, 2011). Tiainen’s is a traditional story about a girl growing up and surviving, but the novel’s strong points are the authentic description of everyday multiculturalism, and the intensity of the narration. The reader identifies with Tara’s balancing act, which she must carry out in the crossfire of her father’s authority, family tradition, and her own dreams. In spite of everything, the community also becomes a source of security and support for Tara. The narrative arc is coherent and, despite the numerous overlapping time-frames, the tension is sustained right up to the final, conciliatory solution.

Translated by Fleur Jeremiah and Emily Jeremiah

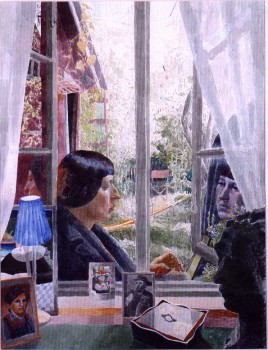

In the mirror

5 April 2011 | Reviews

Aila Meriluoto. Photo: Tiina Pyrylä/WSOY

One of the more attractive aspects of Finnish literature is the juxtaposition of poetry-writing generations. 2011 sees the debut of both the 82-year-old Martta Rossi and new poets born in the 1980s.

Compared to them, the 87-year-old Aila Meriluoto is an old hand: Tämä täyteys, tämä paino (‘This fullness, this weight’, WSOY, 2011) is her 14th volume of poetry.

Since her first collection, which appeared 65 years ago, the grande dame has published more than 20 works: poetry, prose, diaries, books for children and young people, biographies and translations, among them poetry by Harry Martinson and Rainer Maria Rilke. More…

Scent of greenness

21 April 2011 | Fiction, poetry

‘Time the unstoppable’ features in the last collection of poems, Gramina, by Bo Carpelan (1926–2011), who reads timeless poetry while writing his own verses. In his introduction, Michel Ekman quotes the American poet and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, who thought books should stimulate the reader’s thoughts instead of merely being devoured

Poems from the collection Gramina. Marginalia till Horatius, Vergilius och Dante (‘Gramina. Marginalia to Horace, Virgil and Dante’, Schildts, 2011)

Surf on the net –

in the net you are

with mouse and waiting spider

![]()

Fills life’s piggy bank

until it is emptied

![]()

The paved road of envy

where you stumble

![]()

Be sufficient unto oneself?

And who is this ‘self’

who doesn’t introduce himself? More…

Sun and shade

3 August 2011 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Springtime: the new graduates celebrate the beginning of summer. Photos: ©Jussi Brofeldt

Documentary film-making and photography arrived in Finland in the 1920s with pioneers like Heikki Aho and Björn Soldan, who founded a film company in 1925 in Helsinki. They also took thousands of photographs of their city; in a selection taken in the turbulent 1930s, people go on about their lives, rain or shine

Photographs from Aho & Soldan: Kaupunkilaiselämää – Stadsliv – City life. Näkymiä 1930-luvun Helsinkiin (‘Views of Helsinki of the 1930s’, WSOY, 2011)

Photos: Aho & Soldan@Jussi Brofeldt. Texts, by Jörn Donner and Ilkka Kippola, are published in Finnish, Swedish and English.

The exhibition ‘City life‘ is open at Virka Gallery of the Helsinki City Hall from 1 June to 4 September.

Aho and Soldan were half-brothers, Heikki the eldest son of the writer Juhani Aho (1861–1921; an extract from one of his novels is available here) and the artist Venny Soldan-Brofeldt. (Juhani Aho changed his original Swedish surname, Brofeldt, to Aho in 1907), Björn Soldan was Aho’s son from an extramarital relationship. More…

Eeva-Kaarina Aronen: Kallorumpu [Skull drum]

23 December 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kallorumpu

Kallorumpu

[Skull drum]

Helsinki: Teos, 2011. 390 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-413-1

€ 27.40, hardback

Eeva-Kaarina Aronen (born 1948) did not begin her writing career untill 2005, after a long career as editor of the newspaper Helsingin Sanomat. Her third novel Kallorumpu was shortlisted for the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011. Aronen’s interest in historical characters and themes that challenge historical truth was already evident in the of her first novel Maria Renforsin totuus (‘The truth of Maria Renfors’, Teos, 2005). At the centre of Kallorumpu is the legendary figure of Finland’s Field Marshal C.G. Mannerheim (1867–1951). The book concentrates on the description of one day in November 1935 by an old filmmaker, the narrator of the novel, who is showing his documentary to a small group of viewers in the present day. He comments on his own film, complementing it with stories about Mannerheim’s home in Helsinki. At home the Marshal’s staff – a cook, a maid and a valet – not only provide narrative twists and turns, but also an insight into the class divisions of the Finnish civil war. Aronen’s portrayal of her gallery of characters is an interesting one, and the novel’s demanding structure, with its alternating time zones, is sound.

Translated by David McDuff

A light shining

28 July 2011 | Essays, Non-fiction

Portrait of the author: Leena Krohn, watercolour by Marjatta Hanhijoki (1998, WSOY)

In many of Leena Krohn’s books metamorphosis and paradox are central. In this article she takes a look at her own history of reading and writing, which to her are ‘the most human of metamorphoses’. Her first book, Vihreä vallankumous (‘The green revolution’, 1970), was for children; what, if anything, makes writing for children different from writing for adults?

Extracts from an essay published in Luovuuden lähteillä. Lasten- ja nuortenkirjailijat kertovat (‘At the sources of creativity. Writings by authors of books for children and young people’, edited by Päivi Heikkilä-Halttunen; The Finnish Institute for Children’s Literature & BTJ Kustannus, 2010)

What is writing? What is reading? I can still remember clearly the moment when, at the age of five, I saw signs become meanings. I had just woken up and taken down a book my mother had left on top of the chest of drawers, having read to us from it the previous day. It was Pilvihepo (‘The cloud-horse’) by Edith Unnerstad. I opened the book and as my eyes travelled along the lines, I understood what I saw. It was a second awakening, a moment of sudden realisation. I count that morning as one of the most significant of my life.

Learning to read lights up books. The dumb begin to speak. The dead come to life. The black letters look the same as they did before, and yet the change is thrilling. Reading and writing are among the most human of metamorphoses. More…

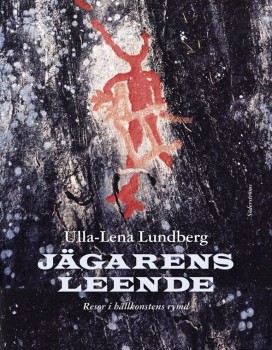

Stories in the stone

2 December 2010 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Extracts from Jägarens leende. Resor in hällkonstens rymd (‘Smile of the hunter. Travels in the space of rock art’, Söderströms, 2010)

‘Why do some people choose to expend what is often a great deal of effort hammering images in the bedrock itself, while others conjure up, in the blink of an eye, brilliantly radiant pictures on a rock-face that was empty yesterday but is now peopled by mythological animals, spirits and shamans?

‘Why do some people choose to expend what is often a great deal of effort hammering images in the bedrock itself, while others conjure up, in the blink of an eye, brilliantly radiant pictures on a rock-face that was empty yesterday but is now peopled by mythological animals, spirits and shamans?

‘I think about this often – I who love painting but who still chose a career that involves me sitting and hammering away, day in and day out, like a true rock-carver,’ writes author and ethnologist Ulla-Lena Lundberg in her new book on the art of the primeval man

When the children of Israel went into Babylonian captivity, hanging up their harps on the willow-trees and weeping as they remembered Zion, my sister and I were already sitting by the rivers of Babylon. We knew how they felt. Our father was dead and we had been sent away from our home. We sat there clinging to each other, or rather I was the one clinging to Gunilla, and she had to try to rouse herself and find something for us to do, to give us something else to think about. More…