Search results for "2011/04/matti-suurpaa-parnasso-1951–2011-parnasso-1951–2011"

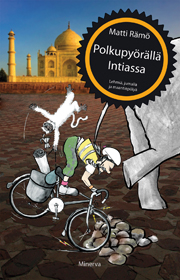

Matti Rämö: Polkupyörällä Intiassa. Lehmiä, jumalia ja maantiepölyä [Cycling in India. Cows, gods, and road dust]

30 July 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Polkupyörällä Intiassa. Lehmiä, jumalia ja maantiepölyä

Polkupyörällä Intiassa. Lehmiä, jumalia ja maantiepölyä

[Cycling in India. Cows, gods, and road dust]

Helsinki: Minerva Kustannus Oy, 2010. 301 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-492-335-4

€ 27.90, hardback

The author decides to take a pinch of the ashes of his dead mother to India’s Varanasi, the city of pilgrims on the banks of the Ganges, and at the same time visit his daughter at an international high school on the country’s west coast. Rämö takes his bicycle on the plane to Delhi and in the course of a month cycles more than 2,600 kilometres, from Delhi to Mumbai. The cyclist is challenged by the heat and humidity, the chaotic traffic, the awkward sections of road and the endless thirst for knowledge on the part of curious bystanders – but his observations are deeper than those of the average travel author, as he worked in India in third world research during the 1980s and 1990s. In the summer of 2007 he completed a four months’ cycle tour of the Sahara, travelling some 9,600 kilometres, and published a book about his experiences (Rengasrikkoja Saharassa, ‘Punctures in the Sahara’, Minerva, 2008). In spite of the shorter length of the Indian journey, the author thinks it possessed a higher difficulty factor.

Jarkko Laine Prize 2011

1 June 2011 | In the news

Juha Kulmala. Photo: Lotta Djupsund

The Jarkko Laine Literary Prize (see our news from 6 May), worth €10,000, was awarded to Juha Kulmala (born 1962) on 19 May for his collection of poems entitled Emme ole dodo (‘We are not dodo’, Savukeidas, 2009).

The prize is awarded to a ‘challenging new literary work’ published during the previous two years. Shortlisted were also two novels, Kristina Carlson’s Herra Darwinin puutarhuri (‘Mr Darwin’s gardener’, Otava, 2009) and Erik Wahlström’s Flugtämjaren (‘Fly tamer’, Finnish translation Kärpäsenkesyttäjä, Schildts, 2010).

Jarkko Laine (1947–2006) was a poet, writer, playwright, translator, long-time editor of the literary journal Parnasso and chair of the Finnish Writers’s Union.

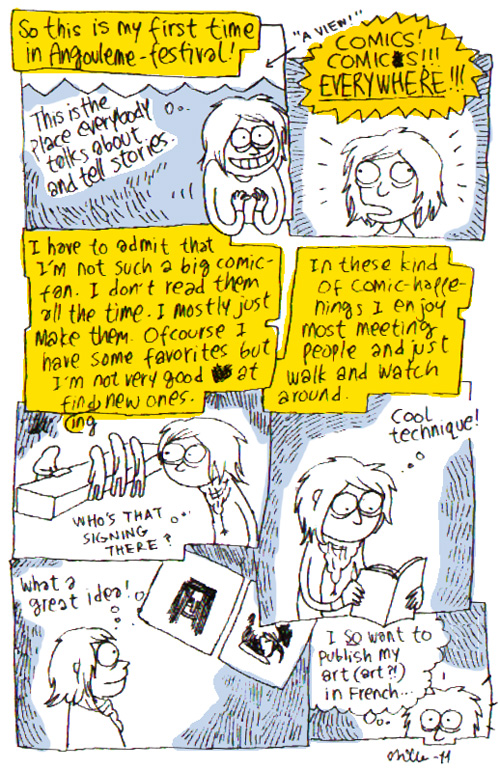

Serious comics: Angoulême 2011

24 February 2011 | This 'n' that

Graphic artist Milla Paloniemi went to Angoulême, too: read more through the link (Milla Paloniemi) in the text below

As a little girl in Paris, I dreamed of going to the Angoulême comics festival – Corto Maltese and Mike Blueberry were my heroes, and I liked to imagine meeting them in person.

20 years later, my wish came true – I went to the festival to present Finnish comics to a French audience! I was an intern at FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange, and for the first time, FILI had its own stand at Angoulême in January 2011.

Finnish comics have become popular abroad in recent years, which is particularly apparent in the young artists’ reception by readers in Europe. Angoulême isn’t just a comics Mecca for Europeans, however: there were admirers of Matti Hagelberg, Marko Turunen and Tommi Musturi from as far away as Japan and Korea.

The festival provides opportunities to present both general ‘official’ comics, ‘out-of-the-ordinary’ and unusual works. The atmosphere at the festival is much wilder than at a traditional book fair: for four days the city is filled with publishers, readers, enthusiasts, artists, and even musicians. People meet in the evenings at le Chat Noir bar to discuss the day’s finds, sketching their friends and the day’s events.

As one Belgian publisher told me, ‘There have always been Finns at Angoulême.’ Staff from comics publisher Kutikuti and many others have been making the rounds at Angoulême for years, walking through the city and festival grounds, carrying their backpacks loaded with books. They have been the forerunners to whom we are grateful, and we hope that our collaboration with them deepens in the future.

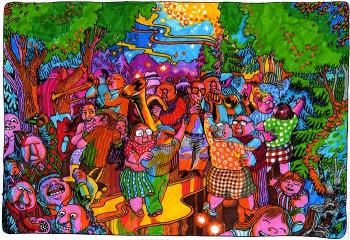

Aapo Rapi: Meti (Kutikuti, 2010)

This year two Finnish artists, Aapo Rapi and Ville Ranta were nominated for the Sélection Officielle prize, which gave them wider recognition. Rapi’s Meti is a colourful graphic novel inspired by his own grandmother Meti [see the picture right: the old lady with square glasses].

Hannu Lukkarinen and Juha Ruusuvuori were also favorites, as all the available copies of Les Ossements de Saint Henrik, the French translation of their adventures of Nicholas Grisefoth, sold out. There were also fans of women comics artists, searching feverishly for works by such artists as Jenni Rope and Milla Paloniemi.

Chatting with French publishers and readers, it became clear that Finnish comics are interesting for their freshness and freedom. Finnish artists dare to try every kind of technique and they don’t get bogged down in questions of genre. They said so themselves at the festival’s public event. According to Ville Ranta, the commercial aspect isn’t the most important thing, because comics are still a marginalised art in Finland. Aapo Rapi claimed that ‘the first thing is to express my own ideas, for myself and a couple of friends, then I look to see if it might interest other people.’

Hannu Lukkarinen emphasised that it’s hard to distribute Finnish-language comics to the larger world: for that you need a no-nonsense agent like Kirsi Kinnunen, who has lived in France for a long time doing publicity and translation work. Finnish publishers haven’t yet shown much interest in marketing comics, but that may change in the future.

These Finnish artists, many of them also publishers, were happy at Angoulême. Happy enough, no doubt, to last them until next year!

Translated by Lola Rogers

Form follows fun

4 December 2012 | Non-fiction, Reviews

The house that the artist built: ‘Life on a leaf’ (2005–2009, Turku). Photo: Vesa Aaltonen

Jan-Erik Andersson: Elämää lehdellä [Life on a leaf]

Helsinki: Maahenki, 2012. 248 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-5872-82-4

€42, hardback

‘I am Leaf House –

root house, sky house.

Enter me, be safe

And wander, dream.

The artist’s I is all our eyes….’

In the garden: red ‘apple’ benches designed by the English artist Trudy Entwistle. Photo: Matti A. Kallio

We all live – exceptions are really rare – in cubes. Not in cylinders or spheres, let alone in buildings of organic shapes like flowers or leaves; and houses in the shape of a shoe, for example, belong to the fairy-tale world, or perhaps to surrealism.

Artist Jan-Erik Andersson wanted to build a fairy-tale house in the shape of a leaf, and that is what he did (2005–2009), together with his architect partner Erkki Pitkäranta. Instead of the geometry of modernist architecture, he is inspired by the organic forms of nature.

Andersson’s house project, entitled ‘Life on a leaf’, also became an academic project, resulting in a dissertation at Finnish Academy of Fine Arts and now a book, including a detailed journal of the building process itself. The artist was at first advised, by a professor of architecture, not to proceed with his building project – he wouldn’t ‘like living in the house’, he was told. More…

Snowbirds

2 November 2011 | Extracts, Non-fiction

The short winter days of the northerly latitudes are made brighter by snow cover, which almost doubles the amount of available light. Reflection from the snow is an aid for photographers working outdoors in winter conditions. A new book, entitled Linnut lumen valossa (‘Birds in the light of snow’), presents the best shots by four professionals, Arto Juvonen, Tomi Muukkonen, Jari Peltomäki and Markus Varesvuo, who specialise in patiently stalking the feathered survivors in the cold

The photographs and texts are from the book Linnut lumen valossa (‘Birds in the light of snow’, edited by Arno Rautavaara. Design and layout by Jukka Aalto/Armadillo Graphics. Tammi, 2011)

Snowy owl. Photo: Markus Varesvuo, 2010

Finlandia Prize candidates 2011

17 November 2011 | In the news

The candidates for the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011 are Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Kristina Carlson, Laura Gustafsson, Laila Hirvisaari, Rosa Liksom and Jenni Linturi.

The candidates for the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011 are Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Kristina Carlson, Laura Gustafsson, Laila Hirvisaari, Rosa Liksom and Jenni Linturi.

Their novels, respectively, are Kallorumpu (‘Skull drum’, Teos), William N. Päiväkirja (‘William N. Diary’, Otava), Huorasatu (‘Whore tale’, Into), Minä, Katariina (‘I, Catherine’, Otava), Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY) and Isänmaan tähden (‘For fatherland’s sake’, Teos).

Kallorumpu takes place in 1935 in Marshal Mannerheim’s house in Helsinki and in the present time. Laila Hirvisaari is a popular writer of mostly historical fiction: Minä, Katariina, a portrait of Russia’s Catherine the Great, is her 39th novel. Gustafsson’s and Linturi’s novels are first works; the former is a bold farce based on women’s mythology, the latter is about guilt born of the Second World War.

The jury – journalist and critic Hannu Marttila, journalist Tuula Ketonen and translator Kristiina Rikman – made their choice out of 130 novels. The winner, chosen by the theatre manager of the KOM Theatre Pekka Milonoff, will be announced on the first of December. The prize is worth 30,000 euros. It has been awarded since 1984, to novels only from 1993.

The fact that this time all the candidates are women has naturally been the object of criticism: why are the popular male writers’ books of 2011 missing from the list?

Another thing that these novels share is history: five of them are totally or partially set in the past – Finland in 1935, Paris in the 1890s, Russia/Soviet Union in the 18th century and in the 1980s, and 1940s Finland during the Second World War. Even the sixth, Huorasatu, bases its depiction of the present day in women’s prehistory, patriarchy and the ancient myths.

The jury’s chair, Hannu Marttila, commented: ‘This book year is sure to be remembered for a generational and gender change among those who write literature about the Second World War in Finland. Young woman writers describe the war with probably greater diversity than before. From the non-fiction writing of recent years it is clear that the struggles and difficulties of the home front are increasingly being recognised as part of the general struggle for survival, and on the other hand the less heroic aspects of war, the shameful and criminal elements, have also become acceptable as objects of study.’

Marttila concluded his speech: ‘When picking mushrooms in the forest, I have learned that it is often worth humbly peeking under the grass, and that the most glaring cap is not necessarily the best…. Perhaps it is time to forget the old saying that there is literature, and then there is women’s literature.’

Findians, Finglish, Finntowns

16 May 2013 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Workers, miners, loggers, idealists, communists, utopians: early last century numerous Finns left for North America to find their fortune, settling down in Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Ontario. Some 800,000 of their descendants now live around the continent, but the old Finntowns have disappeared, and Finglish is fading away – that amusing language cocktail: äpylipai, apple pie.

The 375th anniversary of the arrival of the first Finnish and Swedish settlers, in Delaware, was celebrated on 11 May. Photographer Vesa Oja has met hundreds of American Finns over eight years; the photos and stories are from his new book, Finglish. Finns in North America

Drinking with the workmen: The Työmies Bar. Superior, Wisconsin, USA (2007)

The Työmies Bar is located in the former printing house of the Finnish leftist newspaper, Työmies (‘The workman’). The owners, however, don’t know what this Finnish word means, or how to pronounce it.

The Työmies Society, which published the newspaper of the same name, Työmies, was founded in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1903 as a socialist organ. It moved to Hancock, Michigan the following year. More…

Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011

1 December 2011 | In the news

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011, worth €30,000, is Rosa Liksom, for her novel Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY): read translated extracts and an introduction of the author here on this page.

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011, worth €30,000, is Rosa Liksom, for her novel Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY): read translated extracts and an introduction of the author here on this page.

The prize was awarded on 1 December. The winner was selected by the theatre manager Pekka Milonoff from a shortlist of six.

‘Hytti nro 6 is an extraordinarily compact, poetic and multilayered description of a train journey through Russia. The main character, a girl, leaves Moscow for Siberia, sharing a compartment with a vodka-swilling murderer who tells hair-raising stories about his own life and about the ways of his country. – Liksom is a master of controlled exaggeration. With a couple of carefully chosen brushstrokes, a mini-story, she is able to conjure up an entire human destiny,’ Milonoff commented.

Author and artist Rosa Liksom (alias Anni Ylävaara, born 1958), has since 1985 written novels, short stories, children’s book, comics and plays. Her books have been translated into 16 languages.

Appointed by the Finnish Book Foundation, the prize jury (journalist and critic Hannu Marttila, journalist Tuula Ketonen and translator Kristiina Rikman) shortlisted the following novels: Kallorumpu (‘Skull drum’, Teos) by Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, William N. Päiväkirja (‘William N. Diary’, Otava) by Kristina Carlson, Huorasatu (‘Whore tale’, Into) by Laura Gustafsson, Minä, Katariina (‘I, Catherine’, Otava) by Laila Hirvisaari, and Isänmaan tähden (‘For fatherland’s sake’, first novel; Teos) by Jenni Linturi.

Rosa Liksom travelled a great deal in the Soviet Union in the 1980s. She said she hopes that literature, too, could play a role in promoting co-operation between people, cultures and nations: ‘For the time being there is no chance of some of us being able to live on a different planet.’

Best Translated Book Award 2011

13 May 2011 | In the news

Thomas Teal’s translation from Swedish into English of Tove Jansson’s novel Den ärliga bedragaren (Schildts, 1982), entitled The True Deceiver (published by New York Review Books, 2009), won the 2011 Best Translated Book Award in fiction (worth $5,000; supported by Amazon.com). The winning titles and translators for this year’s awards were announced on 29 April in New York City as part of the PEN World Voices Festival.

Thomas Teal’s translation from Swedish into English of Tove Jansson’s novel Den ärliga bedragaren (Schildts, 1982), entitled The True Deceiver (published by New York Review Books, 2009), won the 2011 Best Translated Book Award in fiction (worth $5,000; supported by Amazon.com). The winning titles and translators for this year’s awards were announced on 29 April in New York City as part of the PEN World Voices Festival.

Organised by Three percent (the link features a YouTube recording from the award ceremony, introducing the translator, Thomas Teal [fast-forward to 7.30 minutes]) at the University of Rochester, and judged by a board of literary professionals, the Best Translated Book Award is ‘the only prize of its kind to honour the best original works of international literature and poetry published in the US over the previous year’. ‘Subtle, engaging and disquieting, The True Deceiver is a masterful study in opposition and confrontation’, said the jury.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001), mother of the Moomintrolls, story-teller and illustrator of children’s books, translated into 40 languages, began to write novels and short stories for adults in her later years. Psychologically sharp studies of relationships, they are written with cool understatement and perception.

Quality writing will work its way into a wider knowledge (i.e. a bigger language and readership) eventually… even though occasionally it may seem difficult to know where exactly it comes from; in a review published in the London Guardian newspaper, the eminent writer Ursula K. Le Guin assumed Tove Jansson was Swedish.

Government Prize for Translation 2011

24 November 2011 | In the news

María Martzoúkou. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

The Finnish Government Prize for Translation of Finnish Literature of 2011 – worth € 10,000 – was awarded to the Greek translator and linguist María Martzoúkou.

Martzoúkou (born 1958), who lives in Athens, where she works for the Finnish Institute, has studied Finnish language and literature as well as ancient Greek at the Helsinki University, where she has also taught modern Greek. She was the first Greek translator to publish translations of the Finnish epic, the Kalevala: the first edition, containing ten runes, appeared in 1992, the second, containing ten more, in 2004.

‘Saarikoski was the beginning,’ she says; she became interested in modern Finnish poetry, in particular in the poems of Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983). As Saarikoski also translated Greek literature into Finnish, Martzoúkou found herself doubly interested in his works.

Later she has translated poetry by, among others, Tua Forsström, Paavo Haavikko, Riina Katajavuori, Arto Melleri, Annukka Peura, Pentti Saaritsa, Kirsti Simonsuuri and Caj Westerberg.

Among the Finnish novelists Martzoúkou has translated are Mika Waltari (five novels; the sixth, Turms kuolematon, The Etruscan, is in the printing press), Väinö Linna (Tuntematon sotilas, The Unknown Soldier) and Sofi Oksanen (Puhdistus, Purge).

María Martzoúkou received her award in Helsinki on 22 November from the minister of culture and sports, Paavo Arhinmäki. Thanking Martzoúkou for the work she has done for Finnish fiction, he pointed out that The Finnish Institute in Athens will soon publish a book entitled Kreikka ja Suomen talvisota (‘Greece and the Finnish Winter War’), a study of the relations of Finland and Greece and the news of the Winter War (1939–1940) in the Greek press, and it contains articles by Martzoúkou.

The prize has been awarded – now for the 37th time – by the Ministry of Education and Culture since 1975 on the basis of a recommendation from FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange.

See the big picture?

9 November 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Details from the cover, graphic design: Työnalle / Taru Staudinger

In his new book Miksi Suomi on Suomi (‘Why Finland is Finland’, Teos, 2012) writer Tommi Uschanov asks whether there is really anything that makes Finland different from other countries. He discovers that the features that nations themselves think distinguish them from other nations are often the same ones that the other nations consider typical of themselves…. In Finland’s case, though, there does seem to be something that genuinely sets it apart: language. In these extracts Uschanov takes a look at the way Finns express themselves verbally – or don’t

Is there actually anything Finnish about Finland?

My own thoughts on this matter have been significantly influenced by the Norwegian social scientist Anders Johansen and his article ‘Soul for Sale’ (1994). In it, he examines the attempts associated with the Lillehammer Winter Olympics to create an ‘image of Norway’ fit for international consumption. Johansen concluded at the time, almost twenty years ago, that there really isn’t anything particularly Norwegian about contemporary Norwegian culture.

There are certainly many things that are characteristic of Norway, but the same things are as characteristic of prosperous contemporary western countries in general. ‘According to Johansen, ‘Norwegianness’ often connotes things that are marks not of Norwegianness but of modernity. ‘Typically Norwegian’ cultural elements originate outside Norway, from many different places. The kind of Norwegian culture which is not to be found anywhere else is confined to folk music, traditional foods and national costumes. And for ordinary Norwegians they are deadly boring, without any living link to everyday life. More…

Finlandia Junior Prize 2011

7 December 2011 | In the news

The musician Paula Vesala has chosen, from a shortlist of six, a book for young people by the poet Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen, Valoa valoa valoa (‘Light light light’, Karisto). The story, which is set at the time of the Chernobyl nuclear power station disaster, poetically describes the passion and pain of first love, longing for mother and death.

The musician Paula Vesala has chosen, from a shortlist of six, a book for young people by the poet Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen, Valoa valoa valoa (‘Light light light’, Karisto). The story, which is set at the time of the Chernobyl nuclear power station disaster, poetically describes the passion and pain of first love, longing for mother and death.

‘Not just what is told, but how it is told. The rythm and timbre of Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen’s language are immensely beautiful. Her phrases do not exist merely to tell the story, but live like poetry or song. Valoa valoa valoa does not incline toward young people from the world of adults; rather, its voice comes, direct and living, from painful, confusing, complex youth, in which young people should really be protected from adults and their blindness. I would have liked to read this book when I was fourteen,’ commented Vesala.

The other five shortlisted books were a picture book for small children, Rakastunut krokotiili (‘Crocodile in love’, Tammi) by Hannu Hirvonen & Pia Sakki, a philosophical picture book about being different and courageous entitled Jättityttö ja Pirhonen (‘Giant girl and Pirhonen’, Tammi) by Hannele Huovi and Kristiina Louhi; a dystopic story set in the 2300s, Routasisarukset (‘Sisters of permafrost’, WSOY), by Eija Lappalainen & Anne Leinonen; a novel about the war experiences of an Ingrian family, Kaukana omalta maalta (‘Far away from homeland’, WSOY) by Sisko Latvus and an illustrated book about gods and myths of the world, Taivaallinen suurperhe (‘Extended heavenly family’, Otava) by Marjatta Levanto & Julia Vuori.

The prize, awarded by the Finnish Book Foundation on 23 November, is worth €30,000.