Search results for "Riikka/2010/10/riikka-pulkkinen-totta-true"

If grief smoked

31 March 1989 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from six collections of poetry. Introduction by Herbert Lomas

The City

How the houses have ascended in this city,

the abysses deepened, the water blackened,

soon to be creeping along the streets.

The railings are rusting through,

the water table’s rising,

the cellars are slopping.

Fear is rising, or being covered up

behind strangling discretion,

outbreaks of crime.

Sensitivity session

30 June 1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Ja pesäpuu itki (‘And the nesting-tree wept’). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Taito Suutarinen knew quite a bit about Freud. Where Mannerheim’s statue now stands, Taito felt that there ought instead to be an equestrian statue of Sigmund Freud. It would be like truth revealed.

Freud, urging on his trusty stallion Libido, would be clad from head to foot in sexual symbols – hat, trousers, shoes: one hand thrust deep into his pocket, the other grasping a walking-stick. The stick would point eloquently in the direction of the railway tracks, where the red trains slid into the arching womb of the station.

Taito had also attended a couple of seven-day sensitivity training courses, where people expressed their feelings openly, directly and spontaneously. By the end of the first course Taito was so direct and spontaneous that he couldn’t get on with anybody. By the end of the second he was so open that everyone was embarrassed. Every member of the group had cried at least once, except the group leader. Never before had Taito witnessed such power. He could not wait to found a group of his own. Taito’s group met in a basement room, where they reclined on mattresses to assist the liberation process. Everyone was free to have problems, quite openly. You were not regarded as ill: on the contrary, if you realized your problem you were more healthy than a person who still thought he mattered. Moreover, as Taito, fixing you with his piercing gaze, was always careful to emphasize, every problem was ultimately a sexual problem. Taito would spontaneously scratch his crotch as he spoke, making it clear that he himself had virtually no problems left. More…

Midwinter in a minor key

23 December 2009 | Letter from the Editors

Finland’s end-of-year celebrations, both Christmas and New Year, take place in a thoroughly muted mode. At noon on Christmas Eve the Christmas Peace is rung out from the mediaeval cathedral in Turku, with the pious and seldom realised hope that peace and harmony will be unbroken for the following twelve days.

It’s true, though, that there’s little of the carousing that characterises Christmas celebrations further south; by and large, people stay behind closed doors, and there’s plenty of time, in the dark mornings and evenings and the brief twilight between them, to eat and drink and sleep – and, for those whose souls are not entirely claimed by the television and food-induced torpor, to read. More…

Chronicles of crisis

31 December 1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Books from Finland presents here an extract from Dyre prins, a novel by the Finland-Swedish writer Christer Kihlman that is to be published in 1983 by Peter Owen of London under the title Sweet Prince, in a translation by Joan Tate.

Christer Kihlman (born 1930) first became known as a poet; but, after publishing two collections of poetry, he turned to novels. He has been branded a merciless scourge of the bourgeoisie. Equally important in his writing, however, are his masterly psychological analyses, his examination of the myriad aspects of the human personality, his sovereign disregard for taboos and his unflagging search for the truth. His books are about crises – the conflict between the generations, between the individual and society, between opposing political ideologies, between homosexual and heterosexual love. As Ingmar Svedberg remarked in an extensive appreciation of Kihlman’s work that appeared in Books from Finland 1-2/1976, ‘In his perceptive moral analyses, his exploration of the depths of human destructiveness and degradation, Kihlman is sometimes reminiscent of Faulkner.’ Since 1970, Kihlman has published three revealing autobiographical works, two of them dealing with his encounter with South America; Dyre prins, first published in 1975, represents a brief interlude of fiction.

The extract printed below is accompanied with a personal appreciation of the novel by its English translator, Joan Tate

Grandfather’s astonishing revelation gave me a new perspective on my life. I had suddenly been given a concrete, genuine foundation for both my hatred and my self-esteem. In a way I took the story of my origins as an extreme confirmation of the rightness of the Communist interpretation of reality, and at the same time it gave me a wonderful, dazzling sensation of being someone, despite everything, of having a place in a meaningful human perspective of time, despite everything, of being a link, however modest, in the historical family tradition. I did not need to found a dynasty; I already belonged to a dynasty, if only a minor branch. One was less important than the other, and even if the two experiences were irreconcilable and contradictory, they existed all the same in the same consciousness, contained within the same consciousness, my consciousness. I, Donald Blad! More…

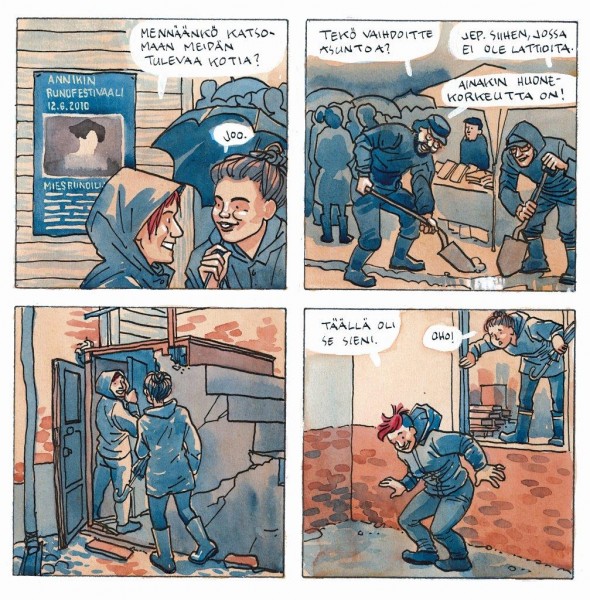

Picture this

9 April 2015 | Articles

It’s impossible to put Finnish graphic novels into one bottle and glue a clear label on to the outside, writes Heikki Jokinen. Finnish graphic novels are too varied in both graphics and narrative – what unites them is their individuality. Here is a selection of the Finnish graphic novels published in 2014

Graphic novels are a combination of image and word in which both carry the story. Their importance can vary very freely. Sometimes the narrative may progress through the force of words alone, sometimes through pictures. The image can be used in very different ways, and that is exactly what Finnish artists do.

In many countries graphic novels share some common style or mainstream in which artists aim to place themselves. In recent years an autobiographical approach has been popular all over the worlds in graphic novels as well as many other art forms. This may sometimes have led to a narrowing of content as the perspective concentrates on one person’s experience. Often the visual form has been felt to be less important, and clearly subservient to the text. This, in turn, has sometimes even led to deliberately clumsy graphic expression.

This is not the case in Finland: graphic diversity lies at the heart of Finnish graphic novels. Appreciation of a fluent line and competent drawing is high. The content of the work embraces everything possible between earth and sky.

Finnish graphic novels are indeed surprisingly well-known and respected internationally precisely for the diversity of their content and their visual mastery.

Life on the block

Cause of death

30 June 1999 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Åtta kroppar (‘Eight bodies’, Söderströms, 1998). Introduction by Ann-Christine Snickars

It was a bailer, a blue one. There they were, he, she, the bailer and a stormtossed net on the stern board of a hired boat. The boat had come with the cottage and the cottage with ‘Autumn archipelago package. Now nature is aglow.’

And it was aglow.

Masses of foliage and apples, damson and shiny russula spread out around them in all their glory. It happened everywhere, that glowing. Wherever one turned one’s gaze there was something ready to be picked or ready to fall, ready in general. Those first days they had, at least to each other, she to him, feigned enthusiasm about all this ripe richness, but that time was over.

Their time of fire and flames was over. More…

How to peel an orange

30 December 2002 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Auringon asema (‘The position of the sun’, Otava, 2002)

There are times when God rules. Then logic is burned on bonfires and left to rot in damp prisons with rats. There are times when logic rules. Then God is burned in the squares and his houses are made into schools. There are times when attempts are made to demonstrate that God and logic can live in the same place and that they are, in fact, the same thing, but those times are truly strange times. And there are times when God and logic live side by side but in different places, like adult siblings who cannot live in the same place but nevertheless get on well together. When my father and my mother loved each other, they were ruled by God, and there was no logic in it, none at all. More…

Best Translated Book Award 2011

13 May 2011 | In the news

Thomas Teal’s translation from Swedish into English of Tove Jansson’s novel Den ärliga bedragaren (Schildts, 1982), entitled The True Deceiver (published by New York Review Books, 2009), won the 2011 Best Translated Book Award in fiction (worth $5,000; supported by Amazon.com). The winning titles and translators for this year’s awards were announced on 29 April in New York City as part of the PEN World Voices Festival.

Thomas Teal’s translation from Swedish into English of Tove Jansson’s novel Den ärliga bedragaren (Schildts, 1982), entitled The True Deceiver (published by New York Review Books, 2009), won the 2011 Best Translated Book Award in fiction (worth $5,000; supported by Amazon.com). The winning titles and translators for this year’s awards were announced on 29 April in New York City as part of the PEN World Voices Festival.

Organised by Three percent (the link features a YouTube recording from the award ceremony, introducing the translator, Thomas Teal [fast-forward to 7.30 minutes]) at the University of Rochester, and judged by a board of literary professionals, the Best Translated Book Award is ‘the only prize of its kind to honour the best original works of international literature and poetry published in the US over the previous year’. ‘Subtle, engaging and disquieting, The True Deceiver is a masterful study in opposition and confrontation’, said the jury.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001), mother of the Moomintrolls, story-teller and illustrator of children’s books, translated into 40 languages, began to write novels and short stories for adults in her later years. Psychologically sharp studies of relationships, they are written with cool understatement and perception.

Quality writing will work its way into a wider knowledge (i.e. a bigger language and readership) eventually… even though occasionally it may seem difficult to know where exactly it comes from; in a review published in the London Guardian newspaper, the eminent writer Ursula K. Le Guin assumed Tove Jansson was Swedish.

Suburban dreams

30 March 2004 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Kahden ja yhden yön tarinoita (‘Tales from two and one nights’, Sammakko, 2003)

Reponen, Tane, Aleksi and Little Juha; once we all climbed up the path to the old dump with bows on our backs, our arrows sticking out from the tops of our boots. It was April. In the field above the dump puddles reflected the opaque sky, where we were going to shoot our arrows.

The field was the highest point in our neighbourhood. We could see the shopping centre, the library and the sawdust running track through the school woods. We could see the high-rise flats on Tora-alhontie road and the huts in the allotments. We could make out the thick spruce forest of Sovinnonvuori along the greenish grey coastline at Kapeasalmi. Our homes sat there below us. Softly droning cranes, yellow totem animals of hope, swung back and forth above the unfinished houses. In the distance was the centre of town with all its churches and scars. Here everything was just beginning. The swaggering confidence of ten-year-old boys was straining within us and would carry us far like Geronimo’s bow. More…