Search results for "jarkko/2009/09/what-god-said"

The attentive lover

31 December 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

In this short story, from his collection Pronssikausi (‘The bronze age’, 1988, on the Finlandia Prize shortlist in 1989), Martti Joenpolvi takes up the subject of the problematic transportation of a human cargo

He braked abruptly; the woman lurched forward, straining against the seat belt, and the car drove into the parking space. The only vehicle parked there was a solitary trailer loaded with timber: a resinous pulpwood-odour came wafting through their open window, so physical, it was as if someone were snooping into the car’s most intimate interior. When they stopped, they got the whiff of a yellow refuse bin, incubated in the heat of the day.

‘What’s up?’

‘We’ve got a problem.’ More…

Losing it

31 March 2002 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Jalat edellä (‘Feet first’, Otava 2001). Introduction by Kanerva Eskola

Once he had sat in the car for a while Risto could feel his thoughts slowly becoming clearer. Tero had been killed by a lorry. He couldn’t think particularly actively about it but perhaps he could have said it out loud. After all, people often say all kinds of things that they don’t think. Maybe even too often, he wondered and decided to have a go.

‘Tero is dead,’ he said and the words tasted of preserved cherries.

In the changing room at the swimming pool Risto noticed that his swimming trunks and towel were mouldy. He had forgotten to hang them up to dry after the last time he went swimming. That was a thousand years ago and now a bluish grey fur was growing on them. He examined the bitter smelling mould on his trunks; the fur was beautiful, smooth and silky like a rabbit’s coat. He gently stroked his trunks. I can use these for ice swimming, he decided, and began to chuckle quietly to himself.

The bully

31 March 1996 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Tulen jano (‘Thirst for fire’, Gummerus, 1995); power relations between doctor and patient in a situation where the past will not leave either alone

Nurmikallio, an apparently ordinary middle-aged man, came back again and again, and it seemed as if there would be no end to his story.

I listened to him patiently at first. Repeatedly he returned to the same subject. The form and emphases of the story changed, new memories emerged, but the gist was the same: he had failed in his life and believed that the root cause of his failure was a particular person, a childhood class-mate, a bully.

On the basis of his first visit I wrote a short character-sketch:

Intellectually average. Talkative, but by his own account solitary. Difficulties in human relationships, separated, no children. Electrician by profession, says he likes his work. Biggest problem obsessive attachment to childhood traumas.

And that’s all, I thought. But he was not to be so easily dismissed.

Arska

30 September 1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Kaksin (‘Two together’). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

A landlady is a landlady, and cannot be expected – particularly if she is a widow and by now a rather battered one – to possess an inexhaustible supply of human kindness. Thus when Irja’s landlady went to the little room behind the kitchen at nine o’clock on a warm September morning, and found her tenant still asleep under a mound of bedclothes, she uttered a groan of exasperation.

“What you do here this hour of day?” she asked, in a despairing tone. “You don’t going to work?”

Irja heaved and clawed at the blankets until at last her head emerged from under them.

“No,” she replied, after the landlady had repeated the question.

“You gone and left your job again?”

“Yep.” More…

Front-Line Tourists

30 September 1976 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Nahkapeitturien linjalla (‘On the tanners’ line’, 1976)

Paavo Rintala (born 1930) published his first novel in 1954 and since then has brought out a new book almost every year. A merciless critic of the myths surrounding certain national figures and events, he has written about Marshal Mannerheim, against attempts to glorify war, and the ‘inevitability’ of Finland’s involvment in the German Barbarossa plan. He has made considerable use of reportage technique to produce anti-war documentaries and in more recent years worked with international subjects.

His books have been widely translated and are popular in East and West Europe. Paavo Rintala’s novel Sissiluutnantti (‘Commando Lieuenant’, Otava 1963) and its reception were the subject of a book by the ltterary critic Pekka Tarkka (Paavo Rintalan saarna ja seurakunta. ‘Paavo Rintala’s sermon and congregation’, Otava 1966). Paavo Rintala is chairman of the Finnish Peace Committee. The passage below is taken from Nahkapeitturien linjalla (‘On the tanners’ line’, Otava 1976) in which he again turns his attention to the war years. Rintala looks at the events of the years leading up to the war and the course of the war itself through the eyes of many different people – from the leading politicians of the day to the ordinary soldier.

The novel has already been acclaimed as the monument to the ‘unknown soldier’ of the Winter War.

![]()

Hessu duly presented himself at the Viipuri office of the Army Information Department (Visitors’ Escort Section), where it was implied that the expected visitors were Very Important People and that a singular privilege was being conferred upon Hessu and such front-line troops that the party might visit. Although His Excellency Field-Marshal Mannerheim made it a rule never to allow front-line visits by ordinary journalists or even by special correspondents, these gentlemen were, it seemed, such influential people that H.E. had agreed to their visit without demur. “You understand, Padre, what a great responsibility this will be for you? These are very high-up people.” More…

The report

30 September 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Kesä ja keski-ikäinen nainen (‘Summer and the middle-aged woman’) Introduction by Margareta N. Deschner

Dear Colleague,

First of all, I want to thank you and your wife for the pleasant evening I and my wife had in your summer villa in August. Briitta (since we are old acquaintances: with two i’s and two t’s, remember?) especially wants me to mention that she will never forget the half moon climbing the hill behind your sauna, surprising us with its speed. The next time we looked it was half-way up the sky! Without doubt, your fine tequila had something to do with the matter, one shouldn’t forget that. Even so, it was quite a show, just like the time a bunch of us guys had gone skiing and you bragged that you had arranged for the barn to catch fire. I hope that you and your wife – I mean Alli – will be able to visit us next winter and taste a superb Mallorca red wine called Comas, which we brought home. It is by far the best red I have ever tasted and indecently cheap to boot. I hope you will come soon. The wine won’t keep indefinitely, as you well know. We’ll save it for you. So thanks again.

Teemu Kupiainen & Stefan Bremer

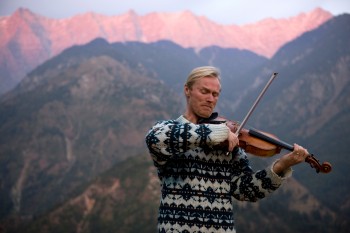

Music on the go

3 March 2010 | Extracts, Non-fiction

A little night music: Teemu Kupiainen playing in Baddi, India, as the sun sets. Photo: Stefan Bremer (2009)

It was viola player Teemu Kupiainen‘s desire to play Bach on the streets that took him to Dharamsala, Paris, Chengdu, Tetouan and Lourdes. Bach makes him feel he is in the right place at the right time – and playing Bach can be appreciated equally by educated westerners, goatherds, monkeys and street children, he claims. In these extracts from his book Viulun-soittaja kadulla (‘Fiddler on the route’, Teos, 2010; photographs by Stefan Bremer) he describes his trip to northern India in 2004.

In 2002 I was awarded a state artist’s grant lasting two years. My plan was to perform Bach’s music on the streets in a variety of different cultural settings. My grant awoke amusement in musical circles around the world: ‘So, you really do have the Ministry of Silly Walks in Finland?’ a lot of people asked me, in reference to Monty Python. More…

Looking back on a dark winter

31 December 1989 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the autobiographical novel Talvisodan aika (‘The time of the Winter War’), the childhood memoirs of Eeva Kilpi. During the winter of 1939–40 she was an 11-year old-schoolgirl in Karelia when it was ceded to the Soviet Union and the population evacuated

Time is the most valuable thing

we can give each other

War’s coming.

One day my father comes out with the familiar words in a totally unfamiliar way, while we’re sitting round the kitchen table eating, or just starting to eat.

He says to mother, as if we simply aren’t there, as if we don’t need to bother, or as if listening means not understanding. Or perhaps they’ve simply no other chance to speak to each other, as father’s always got to be off hunting, or on his way to the station, and mother’s always cooking. More…

Hotel for the living

30 June 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Hotelli eläville (‘Hotel for the living’, 1983). Introduction by Markku Huotari

Raisa and Pertti are a married couple with three children, Katrielina, Aripertti and Artomikko. When she discovers she is to have another, whom she names Katjaraisa, Raisa decides to have an abortion, because another child, even if welcome, would now jeopardise her career – she has been offered a job with an international company at the very top of the advertising world. Raisa is the successful entrepreneur of the novel – on the one hand coldly calculating, without feeling, on the other superficially sentimental, perhaps the most startlingly ironic of the characters in Jalonen’s novel. His image of the brave new woman?

During her lunch hour Raisa took a walk via the laboratory, asked reception for the envelope and thrust it unregarded into her handbag. She was aware of her already knowing, but short of the envelope, there would as yet be no restrictions, nor were there any decisions that would have to be made. She had called Tom Eriksson, discussed yet again the same points and particulars, and ended tracing a finger over the two beautiful pictures on her wall. ‘The loveliest of seas has yet to be sailed’ and ‘I am life! For Life’s sake.’

She thought of Katjaraisa, her features, the palms the breadth of two fingers, just as Katrielina’s had been, and the same button-eyed gazing look as Katrielina. More…

The Finlandia prizes: Non-fiction, Junior

28 November 2013 | In the news

Ville Kivimäki. Photo: Pertti Nisonen

The Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2013, worth €30,000, was awarded on 21 November to the historian Ville Kivimäki for his book Murtuneet mielet. Taistelu suomalaissotilaiden hermoista 1939–1945 (‘Broken minds. The battle ofor the nerves of Finnish soldiers 1939–1945’, WSOY).

The other works on the shortlist of six were as follows: 940 päivää isäni muistina (‘940 days as my father’s memory’, Teos; a book on Alzheimer’s disease) by Hanna Jensen, Kokottien kultakausi: Belle Epoquen mediatähdet modernin naiseuden kuvastimina (‘The golden era of the cocottes: the media stars of Belle Epoque as mirrors of modern femininity’, Finnish Literature Society) by Harri Kalha, Viipuri 1918 (‘Vyborg 1918’, Siltala) by Teemu Keskisarja, Suomi öljyn jälkeen (‘Post-oil Finland’, Into) by Rauli Partanen, Harri Paloheimo and Heikki Waris and Vapaalasku – tieto, taito, turvallisuus (‘Freestyle – knowledge, skill, safety’, Kustannus Oy Vapaalasku) by Matti Verkasalo, Jarkko-Juhani Henttonen and Kai Arponen.

The prize-winner was chosen by the director of the Ateneum Art Museum, Maija Tanninen–Mattila. In her celebratory speech she said: ‘The symptoms of many psychologically disturbed soldiers remained untreated during the war. For many, their symptoms appeared only after the war. Their experiences have remained unexpressed in language, the history of those who lack history. Ville Kivimäki has given voice to these experiences… and succeeded in writing a book that speaks across the generations.’

In his acceptance speech Ville Kivimäki (born 1976) commented: ‘The great majority of the war generation is now dead, and the words of a youngish scholar cannot, even when successful, reach those traumatic experiences whose depth we can never fully understand. But all the same, I would like to take this opportunity to say something that should have been said years ago: the psychological injuries of the war were war wounds in exactly the same sense as physical ones. In the end anyone could suffer a psychological breakdown.’

Kreetta Onkeli. Photo: Jouni Harala

The Finlandia Junior Prize 2013 was awarded on 26 November, also worth €30,000. It went to Kreetta Onkeli for her book Poika joka menetti muistinsa (‘The boy who lost his memory’, Otava).

Arto, 12, gets such a massive fit of laughter that he loses his memory and needs to find his identity and his home in contemporary Helsinki.

The winner was chosen from the shortlist of six by Jarno Leppälä, a media personality and member of the popular stunt group Duudsonit, the Dudesons. At the award ceremony he said:

‘Poika joka menetti muistinsa is, in my opinion, a well-written story about how young people in society are put on the same starting line and expected to do equally well in all circumstances – often irrespective of the fact that their starting points may actually be very different, and completely independent of the young people themselves.’

Kreetta Onkeli (born 1970) explained in her award speech how her aim was to write a proper, old-fashioned novel for children: ‘Not hundreds of pages of magic tricks but ordinary, real contemporary life that children could identify with.’ In her opinion the current, massive trend of fantasy has narrowed the scope of children’s literature.

The following five books made it on to the shortlist: Poika (‘The boy’, Like), about a boy who feels he was born in the wrong gender by Marja Björk, Hipinäaasi, apinahiisi (onomatopoetic pun, ‘Donkeymonkey’, Tammi), about bullying and friendship, written by Ville Hytönen and illustrated by Matti Pikkujämsä, Isä vaihtaa vapaalle (‘Father on his own time’, WSOY), an illustrated story about children with too busy parents, written by Jukka Laajarinne and illustrated by Timo Mänttäri, Aapine (‘ABC’, Otava), an illustrated primer written by Heli Laaksonen in her own south-western dialect and illustrated by Elina Warsta and Vain pahaa unta (‘Just a bad dream’, WSOY) by graphic designer and writer Ville Tietäväinen and his daughter Aino, a book on a child’s nightmares.

Finlandia literary prizes are awarded by Suomen Kirjasäätiö, The Finnish Book Foundation, established in 1983.

The first Finlandia Prize for Fiction was awarded in 1984. This year it will be announced on 3 December.

Literary prizes: the Dancing Bear 2009

21 May 2009 | In the news

Sanna Karlström. - Photo: Irmeli Jung

This year’s Dancing Bear Poetry Prize, worth €3,500, has gone to Sanna Karlström (born 1975) for her third collection of poems, Harry Harlow’n rakkauselämät (‘The love lives of Harry Harlow’, WSOY, 2008). The prize is awarded every May by the Finnish Broadcasting Company to a book of poetry published the previous year. It was given this year for the 16th time.

The collection, containing short, condensed tales of love and lovelessness, forms a fragmented portrait of the American psychologist Harry Harlow who, in the 1950s, made notorious experiments with young rhesus monkeys in which he separated them from their mothers.

Chosen by a jury of three radio journalists, Barbro Holmberg, Marit Lindqvist and Tarleena Sammalkorpi, and the poet Risto Oikarinen, the other shortlisted authors were Ralf Andtbacka, Kari Aronpuro, Eva-Stina Byggmästar, Jouni Inkala and Silja Järventausta.

For your eyes only

11 May 2015 | This 'n' that

Photo: Steven Guzzardi / CC BY-ND 2.0

Imagine this: you’re a true bibiophile, with a passion for foreign literature (not too hard a challenge, surely, for readers of Books from Finland,…). You adore the work of a particular writer but have come to the end of their work in translation. You know there’s a lot more, but it just isn’t available in any language you can read. What do you do?

That was the problem that confronted Cristina Bettancourt. A big fan of the work of Antti Tuuri, she had devoured all his work that was available in translation: ‘It has everything,’ she says, ‘Depth, style, humanity and humour.’

Through Tuuri’s publisher, Otava, she laid her hands on a list of all the Tuuri titles that had been translated. It was a long list – his work has been translated into more than 24 languages. She read everything she could. And when she had finished, the thought occurred to her: why not commission a translation of her very own? More…

At the sand pit

30 September 1985 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Antti Tuuri. Photo: Jouni Harala

‘After nearly 40 years of observing the Ostrobothnians, I am convinced that they have certain characteristics which explain the historical events that took place there and which also shed light on the region today. I do not know how these characteristics develop, but it appears that heredity, economic factors and even the landscape form the nature of people. Everywhere people who live in the plains are different from those who dwell in the mountains, and from those who fish the archipelagos,’ writes the author Antti Tuuri, himself an Ostrobothnian.

Antti Tuuri’s Pohjanmaa (‘Ostrobothnia’, 1982), which last January was awarded the Nordic Prize for Literature, has now been translated into each language of the Nordic countries. Tuuri’s novel describes the events of one summer day in Ostrobothnia, on the west coast of Finland, where a farming family, the Hakalas, has gathered for the reading of the will of a grandfather who emigrated to the United States in the 1920s.

The inheritance itself is insignificant, but it has brought together the four grandsons, with their wives and children. The story is narrated from the point of view of one of the brothers. The women of the family remain inside while the men take out an automatic pistol which has been kept hidden away since one of them smuggled it home from the Continuation War. The men go off to a sand pit to do some shooting and to drink some illegal home brew. There they meet their former schoolteacher, who joins in with their drinking and shooting. Some surprising events take place as the day’s action unfolds, and Tuuri’s narrator views them in an unsentimental way, describing them matter-of-factly and at times with ironic humour. The men recall the violent history of Ostrobothnia, the years of the Civil War and the right-wing Lapua movement of the 1930s.

The Nordic Prize jury commented that the novel ‘portrays the breaking up of the old society, and conflicts between generations as well as between men and women.’ Tuuri has constructed his novel on conflicts, and the result is a highly dramatic narrative.

![]()

An extract from Pohjanmaa (‘Ostrobothnia’)

A Finnish hound dog came out of the woods just beyond the sandpit, stopped at the edge of the pit and started to bark at us. The boys quickly began putting the weapon together. Veikko yelled that you were allowed to shoot a dog running loose in the woods out of hunting season. He kept asking me for cartridges; he’d shoot the dog right away, before it could tear to pieces the young game birds that couldn’t fly yet. I told him to shut up. Seppo finished putting the automatic pistol together and gave it to me. I ran to the car, put the gun down on the floor in front of the back seat and tossed a blanket over it.

When I got back, I saw the teacher coming out of the woods over by the pit. He snapped a leash on the dog and started towards us through the pine grove. The boys sat down around the campfire and began taking swigs of home brew from their cups. More…