Search results for "jarkko/2011/04/2010/05/2009/10/writing-and-power"

Funny ha ha?

3 March 2010 | This 'n' that

Comic books, graphic novels: the popularity of stories in pictures keeps on growing everywhere – and they may or not may be ‘comical’.

Comic books, graphic novels: the popularity of stories in pictures keeps on growing everywhere – and they may or not may be ‘comical’.

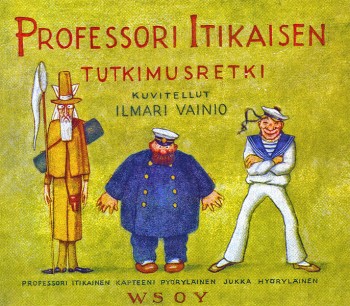

In Finland, sarjakuva (lit. serial picture) will celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2011. The first Finnish picture story, Professori Itikaisen tutkimusretki (‘Professor Itikainen’s expedition’, WSOY), by Ilmari Vainio, was published in 1911.

Ilmari Vainio (1892–1955) was a customs official who later also published two fairy tales and two handbooks for boy scouts. Professor Itikainen is a scientist who sets out on the sea and then finds himself, together with two brave seamen, facing various dangers in Africa, China and on the North Pole. A happy ending ensues in the form of safe arrival back in Helsinki on page 48. More…

Johanna Ilmakunnas: Kapiot, kartanot, rykmentit. Erään aatelissuvun elämäntapa 1700-luvun Ruotsissa [Trousseaus, manors, regiments. The lifestyle of one noble house in 18th-century Sweden]

28 July 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kapiot, kartanot, rykmentit. Erään aatelissuvun elämäntapa 1700-luvun Ruotsissa

Kapiot, kartanot, rykmentit. Erään aatelissuvun elämäntapa 1700-luvun Ruotsissa

[Trousseaus, manors, regiments. The lifestyle of one noble house in 18th-century Sweden]

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2011. 524 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-264-0

€ 38, hardback

This book deals with the lifestyles, finances and consumption habits of the high nobility of Sweden in the 18th century (which included Finland at that time). The central figure is Count Axel von Fersen (1719–1794), a very influential statesman and soldier, and his German-Baltic lineage. This portrait broadens into a lifestyle study, providing extensive information on the customs and the world of the nobility of that era, such as the institution of marriage, child-rearing, mistresses, clothing and interior decor – as indicators of one’s social status – artistic activities, games and gastronomy. The topic of consumption is linked to social, cultural, ideological and legal perspectives. In the lives of the high nobility, money – or lack thereof – was not a defining feature; rather, choices were governed by ideals, values and obligations such as honour, reputation, faith and origin. Johanna Ilmakunnas is a historical researcher and editor. This book is based on her award-winning doctoral thesis (2009).

Translated by Ruth Urbom

New from the archives

13 March 2015 | This 'n' that

Eeva-Liisa Manner. Photo: Tammi.

Today we have a real treat – a selection of the sumptuously minimalist poetry of Eeva-Liisa Manner (1921–1995) by her near-contemporary, the British poet Herbert Lomas (1924–2011).

Born in Helsinki, Manner spent her youth in Viipuri, in what was then part of Finland; her life was, like Eeva Kilpi’s, marked by evacuation from her home and the subsequent loss of Karelia to the Soviet Union in the Second World War. Her breakthrough collection, Tämä matka (‘This journey’, 1956) marked a major arrival on the modernist poetry scene and her work has been widely translated. Always lyrically minimalist, Manner’s poetry sometimes seemed to approach the limits of language – silence:

The words come and go.

I need words less and less.

Tomorrow maybe

I’ll not need a single one,

she wrote in Niin vaihtuvat vuoden ajat (‘So change the seasons’), as early as 1964.

Lomas brought to the delicate, beautiful textures of Manner’s poetry with its themes of grief, suffering and loneliness a bluff Yorkshire, and entirely masculine, sensibility. For him, Manner had a ‘splendid sanity’ and sense of humour; hers was an oeuvre ‘that heals by listening and recovery’.

Manner’s work has more recently been translated by another English writer, Fleur Jeremiah, in a volume entitled Bright, dusky, bright (Waterloo Press, 2009). A sample of the approach taken by a woman of a different generation can be found here.

*

The digitisation of Books from Finland continues apace, with a total of 360 articles and book extracts made available online so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

How Real is a Dead Person?

30 September 1979 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An Extract from the Novel Sirkus (‘Circus’). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Once again I seem to be moving towards a deeper understanding of these people who figure in my recollections, most of whom, by now – by this particular Friday I am now experiencing – are already dead. And this, in its turn, sets me wondering about the degree of reality, if any, that they can claim to possess. How real is a dead person? Is he, perhaps, totally unreal? In memories, of course, he is real to the extent that the memories themselves are real. But objectively, independently of memory? But here a sadness comes over me, many-headed, hard to take hold of.

And in any case I think it is time I came to a clearer understanding of the economic circus founded by my grandfather Feodisius. Uncle Ribodisius has also already made the front pages of the newspapers, and the Bilbao has published an interview.

But I have left a picture unfinished. Father’s cardboard boxes! The separation from Dianita – and from the children! And I have broken off in the middle of these curious memoirs of mine. Thinking of which, I find myself grinding to a halt again, stuck with Yellow-Handed Fred and Haius and Desmer, Lesmer and Sesmer – until I realize that instead of coming to a clearer understanding of my grandfather’s economic circus, I am on Lesmer’s estate, one evening in late May – a couple of months ago – listening to the trilling of an unusually talented song-thrush. Perched on the top of a tall spruce, he goes through the repertoire of all the other birds he has ever heard, both native and foreign – creating, however, new combinations of his own; not content with mere mimicry, he rattles, croons, wails, whistles, whirrs, twitters, flutes, sighs, chirrups and shouts his way through a complete set of variations on themes provided by the rest of the bird world: like some rather advanced medieval chronicler who, no longer content to record faithfully (if perhaps chaotically, as Auerbach points out) what he saw, heard, thought and smelt, had begun to create personal shapes and entities – thus preparing the way for the greatest miracle in the history of world literature, the advent of the perceptive reader. More…

Mikko Lahtinen: Kirjastojen maa [Land of libraries]

4 March 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kirjastojen maa

Kirjastojen maa

[Land of libraries]

Tampere: Vastapaino, 2010. 394 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-768-315-9

€ 43, hardback

Libraries are the most widely used cultural service in Finland. Kirjastojen maa describes the journey undertaken by the protagonist, who refers to himself as ‘the Library Man’, and his entourage to 250 public libraries around Finland between 2008 and 2010. Many of these sites were celebrating their 150th anniversaries at the time, since there was a great enthusiasm for establishing public libraries in Finland in the 1850s. This travel journal provides a history of libraries as an institution and their development into a central pillar of society. The author also considers Finnish intellectual space in this age of digital media. Libraries currently face significant challenges: the recent wave of local authority mergers, centralisation of public services and funding cuts are all hampering the development of library operations. The importance of libraries is further underlined by the fact that local residents have launched protests in support of libraries threatened with closure – in spite of the usual difficulty of rousing Finns to man the barricades. The author is a philosopher, political researcher and active participant in public policy discussions.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

Solid, intangible

26 September 2013 | Fiction, poetry

Poems from Mot natten. Dikter 2010 (‘Towards the night. Poems 2010’, Schildts & Söderströms, 2013). Introduction by Michel Ekman

Memory

If you give me time

I don’t weigh it in my hand:

it’s so light, so transparent

and heavy as the thick

shining darkness

in the backyard gateway

to memory

Green thoughts

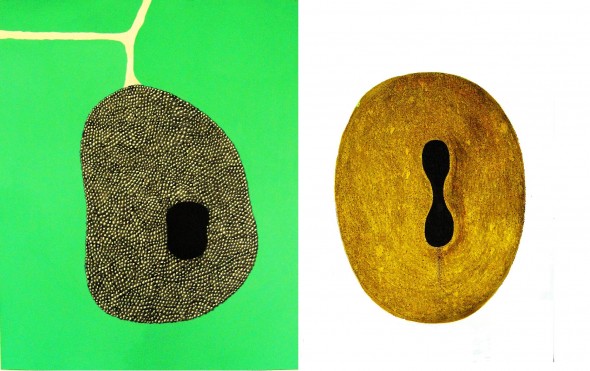

Extracts from the novel Kuperat ja koverat (‘Convex and concave’, Otava, 2010)

I decided to go to the Museum of Fine Arts.

After paying for my entrance ticket, I climbed the wide staircase to the first floor. There all I saw were dull paintings, the same heroic seed-sowers and floor-sanders as everywhere else. Why were so many art museums nothing more than collections of frames? Always national heroes making their horses dance, mud-coloured grumblers and overblown historical scenes. There was not a single museum in which a grandfather would not be sitting on a wobbly stool peering over his broken spectacles, interrogating a young man about to set off on his travels, cheeks burning with enthusiasm, behind them the entire village, complete with ear trumpets and balls of wool. The painting’s eternal title would be ‘Interrogation’ and it would be covered with shiny varnish, so that in the end all you would be able to see would be your own face.

I climbed up to the next floor. All I really felt was a pressing need to run away. No Flemish conversation piece acquired in the Habsburg era was able to erase a growing anxiety related to love. More…

Vesa Sirén: Suomalaiset kapellimestarit. Sibeliuksesta Saloseen, Kajanuksesta Franckiin [Finnish conductors. From Sibelius to Salonen and from Kajanus to Franck]

17 February 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Suomalaiset kapellimestarit. Sibeliuksesta Saloseen, Kajanuksesta Franckiin

Suomalaiset kapellimestarit. Sibeliuksesta Saloseen, Kajanuksesta Franckiin

[Finnish conductors. From Sibelius to Salonen and from Kajanus to Franck]

Helsinki: Otava, 2010. 1,000 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-21203-1

€ 38, hardback

This work, by music critic Vesa Sirén – awarded the Finlandia Prize for non-fiction in 2010 – attempts to explain what makes a good orchestra conductor. Including hundreds of interviews, the book takes a chronological approach, presenting portraits of sixty conductors from the 1880s up to current students of conducting. There are also contributions from music critics, as well as even tougher assessments from musicians, contemporaries of the conductors. The high standard of Finnish music education, which has been easily accessible to young people – at least until the recent times –, provides part of the answer, as does the conducting course at the Sibelius Academy under the long-serving leadership of Jorma Panula. Sirén’s archival research has unearthed some forgotten treasures, including the lost archives of Robert Kajanus and conductor’s notes in Jean Sibelius’ own handwriting.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

Candidates for the Runeberg Prize

23 December 2009 | In the news

Seven books were chosen out of approximately 200 to be the candidates of the Runeberg Prize, to be awarded on 5 February 2010. More…

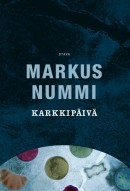

Markus Nummi: Karkkipäivä [Candy day]

26 November 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Karkkipäivä

Karkkipäivä

[Candy day]

Helsinki: Otava, 2010. 383 p.

ISBN 978-951-1-24574-2

€28, hardback

Like this one, Markus Nummi’s previous novel, Kiinalainen puutarha (‘Chinese garden’, 2004), set in Asia at the turn of the 20th century, involves a child’s perspective. Karkkipäivä‘s main theme, however, is a portrait of contemporary Finland. Tomi is a little boy whose alcoholic parents are incapable of looking after him; Mirja’s mother is a frantic workaholic heading for a nervous breakdown. She is a control freak who secretly gorges on chocolate at work and beats her little daughter – a grotesque portrait of contemporary womanhood. Tomi manages to get some adult attention and help from a writer; the relation between them gradually builds into one of trust. Katri is a social worker, empathetic but virtually helpless as part of the social services bureaucracy. Virtually every adult suspects others of lying, finding each other’s motives doubtful. Nummi (born 1959) has structured Karkkipäivä with great skill; the ending, in which matters are resolved almost by chance, is particularly gripping. This novel was nominated for the 2010 Finlandia Prize for Fiction.

A walk on the West Side

16 March 2015 | Fiction, Prose

Hannu Väisänen. Photo: Jouni Harala

Just because you’re a Finnish author, you don’t have to write about Finland – do you?

Here’s a deliciously closely observed short story set in New York: Hannu Väisänen’s Eli Zebbahin voikeksit (‘Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits’) from his new collection, Piisamiturkki (‘The musquash coat’, Otava, 2015).

Best known as a painter, Väisänen (born 1951) has also won large readerships and critical recognition for his series of autobiographical novels Vanikan palat (‘The pieces of crispbread’, 2004, Toiset kengät (‘The other shoes’, 2007, winner of that year’s Finlandia Prize) and Kuperat ja koverat (‘Convex and concave’, 2010). Here he launches into pure fiction with a tale that wouldn’t be out of place in Italo Calvino’s 1973 classic The Castle of Crossed Destinies…

Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits

Eli Zebbah’s small but well-stocked grocery store is located on Amsterdam Avenue in New York, between two enormous florist’s shops. The shop is only a block and a half from the apartment that I had rented for the summer to write there.

The store is literally the breadth of its front door and it is not particularly easy to make out between the two-storey flower stands. The shop space is narrow but long, or maybe I should say deep. It recalls a tunnel or gullet whose walls are lined from floor to ceiling. In addition, hanging from the ceiling using a system of winches, is everything that hasn’t yet found a space on the shelves. In the shop movement is equally possible in a vertical and a horizontal direction. Rails run along both walls, two of them in fact, carrying ladders attached with rings up which the shop assistant scurries with astonishing agility, up and down. Before I have time to mention which particular kind of pasta I wanted, he climbs up, stuffs three packets in to his apron pocket, presents me with them and asks: ‘Will you take the eight-minute or the ten-minute penne?’ I never hear the brusque ‘we’re out of them’ response I’m used to at home. If I’m feeling nostalgic for home food, for example Balkan sausage, it is found for me, always of course under a couple of boxes. You can challenge the shop assistant with something you think is impossible, but I have never heard of anyone being successful. If I don’t fancy Ukrainian pickled cucumbers, I’m bound to find the Belorussian ones I prefer. More…