Search results for "jarkko/2011/04/matti-suurpaa-parnasso-1951–2011-parnasso-1951–2011"

A walk on the West Side

16 March 2015 | Fiction, Prose

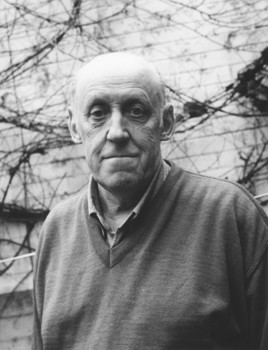

Hannu Väisänen. Photo: Jouni Harala

Just because you’re a Finnish author, you don’t have to write about Finland – do you?

Here’s a deliciously closely observed short story set in New York: Hannu Väisänen’s Eli Zebbahin voikeksit (‘Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits’) from his new collection, Piisamiturkki (‘The musquash coat’, Otava, 2015).

Best known as a painter, Väisänen (born 1951) has also won large readerships and critical recognition for his series of autobiographical novels Vanikan palat (‘The pieces of crispbread’, 2004, Toiset kengät (‘The other shoes’, 2007, winner of that year’s Finlandia Prize) and Kuperat ja koverat (‘Convex and concave’, 2010). Here he launches into pure fiction with a tale that wouldn’t be out of place in Italo Calvino’s 1973 classic The Castle of Crossed Destinies…

Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits

Eli Zebbah’s small but well-stocked grocery store is located on Amsterdam Avenue in New York, between two enormous florist’s shops. The shop is only a block and a half from the apartment that I had rented for the summer to write there.

The store is literally the breadth of its front door and it is not particularly easy to make out between the two-storey flower stands. The shop space is narrow but long, or maybe I should say deep. It recalls a tunnel or gullet whose walls are lined from floor to ceiling. In addition, hanging from the ceiling using a system of winches, is everything that hasn’t yet found a space on the shelves. In the shop movement is equally possible in a vertical and a horizontal direction. Rails run along both walls, two of them in fact, carrying ladders attached with rings up which the shop assistant scurries with astonishing agility, up and down. Before I have time to mention which particular kind of pasta I wanted, he climbs up, stuffs three packets in to his apron pocket, presents me with them and asks: ‘Will you take the eight-minute or the ten-minute penne?’ I never hear the brusque ‘we’re out of them’ response I’m used to at home. If I’m feeling nostalgic for home food, for example Balkan sausage, it is found for me, always of course under a couple of boxes. You can challenge the shop assistant with something you think is impossible, but I have never heard of anyone being successful. If I don’t fancy Ukrainian pickled cucumbers, I’m bound to find the Belorussian ones I prefer. More…

Tuula Kallioniemi: Rottaklaani [The rat clan]

24 February 2009 | Mini reviews

Rottaklaani

Rottaklaani

[The rat clan]

Helsinki: Otava, 2008. 192 p.

ISBN 978-951-1-23159-2

€ 16, hardback

Tuula Kallioniemi (born 1951) manages to deal with difficult issues without resorting to conventional solutions. Ykä, who is nearly 12, suffers from the normal anguish of early adolescence until the CP [cerebral palsy]-disabled Sami pushes his wheelchair into Ykä’s life. The boys decide to get the better of Antikainen who is bullying Sami, but in order to carry out their plan they need the help of quadraplegic Pete and Susanna, who has MBD [minimal brain dysfunction]. Kallioniemi’s literary prescription for the prevention of illness in young people is a simple one: we must all be friends with one other, be allowed to express wonder out loud, and remember that laughter is the best therapy. Kallioniemi’s merits are her verbal skills and her natural cultivation of situation comedy.

Round and round

2 December 2011 | Essays, Non-fiction

In this essay, Olli Löytty imagines himself in a revolving door that is able to spin his old family home and its inhabitants backwards in time – as far as prehistory. In addition to his own family’s past, Löytty zooms back into the history of the world’s great changes, for a moment playing the part of a cosmic god examining our globe

An essay from Kulttuurin sekakäyttäjät (‘Culture-users’, Teos, 2011)

If a film camera had stood outside my home from the time when it was built, I would rewind the movie it made from the end to the beginning. The story would begin with my children, one autumn morning in 2011, walking backwards home from school. The speed of the rewind would be so fast that they would quickly grow smaller; I, too, would get thinner and start smoking. I would curiously seek out the point where my wife and I are seen together for the last time, stepping out of the front door, back first, and setting out on our own paths, to live our own separate young lives.

At that time my grandmother still lives in the house with her two daughters and their husbands, and lodgers upstairs. The next time I would slow the rewind would be the point where, at the age of 18, finally move out of the house. The freeze-frame reveals a strange figure: almost like me, but not quite. In the face of the lanky youth I seek my own children’s features.

When I let the film continue its backwards story, I seek glimpses of myself as a child. Even though we lived in distant Savo [in eastern Finland], we went to see my grandmother in the city of Tampere relatively often. We called her our Pispala grandmother, although her house was located to the west of the suburb limit, in Hyhky. I follow the arrival of my grown-up cousins, their transformation into children, the juvenation of my grandmother and her daughters, the changing lodgers. At some point the film becomes black-and-white. More…

Helene Schjerfbeck. Och jag målar ändå [Helene Schjerfbeck. And I still paint]

16 December 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Helene Schjerfbeck. Och jag målar ändå. Brev till Maria Wiik 1907–1928

Helene Schjerfbeck. Och jag målar ändå. Brev till Maria Wiik 1907–1928

[Helene Schjerfbeck. And I still paint. Letters to Maria Wiik 1907–1928]

Utgivna av [Edited by]: Lena Holger

Helsingfors: Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland; Stockholm: Bokförlaget Atlantis, 2011. 301 p., ill.

ISBN (Finland) 978-951-583-233-7

ISBN (Sweden) 978-91-7353-524-3

€ 44, hardback

In Finnish:

Helene Schjerfbeck. Silti minä maalaan. Taiteilijan kirjeitä

[Helene Schjerfbeck. And I still paint. Letters from the artist]

Toimittanut [Edited by]: Lena Holger

Suomennos [Translated by]: Laura Jänisniemi

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2011. 300 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-305-0

€ 44, hardback

This work contains a half of the collection of some 200 letters (owned by the Signe and Ane Gyllenberg’s foundation), until now unpublished, from artist Helene Schjerfbeck (1862–1946) to her artist friend Maria Wiik (1853–1928), dating from 1907 to 1928. They are selected and commented by the Swedish art historian Lena Holger. Schjerfbeck lived most of her life with her mother in two small towns, Hyvinge (in Finnish, Hyvinge) and Ekenäs (Tammisaari), from 1902 to 1938, mainly poor and often ill. In her youth Schjerfbeck was able to travel in Europe, but after moving to Hyvinge it took her 15 years to visit Helsinki again. In these letters she writes vividly about art and her painting, as well as about her isolated everyday life. Despite often very difficult circumstances, she never gave up her ambitions and high standards. Her brilliant, amazing, extensive series of self-portraits are today among the most sought-after north European paintings; she herself stayed mostly poor all her long life. The book is richly illustrated with Schjerfbeck’s paintings (mainly from the period), drawings and photographs.

Juhani Koivisto: Suurten tunteiden talo. Kohtauksia Kansallisoopperan vuosisadalta [The house of great emotions. Scenes from a century of the Finnish National Opera]

30 June 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Suurten tunteiden talo. Kohtauksia Kansallisoopperan vuosisadalta

Suurten tunteiden talo. Kohtauksia Kansallisoopperan vuosisadalta

[The house of great emotions. Scenes from a century of the Finnish National Opera]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2011. 229 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-0-37667-6

€ 45, paperback

2011 marks the one-hundredth anniversary of the founding of the Finnish National Opera. This richly illustrated and entertaining book describes events that have been absent from previous ‘official’ historical accounts. Readers will encounter over a hundred opera denizens who have made audiences – and, according to many anecdotes, each other – laugh and cry. The initial stages of the opera and ballet were modest in scope when viewed from outside, but the trailblazers involved were tremendous talents and personalities. The brighest star was the singer Aino Ackté, who enjoyed an international reputation. Gossip about intrigues and artistic differences at the opera house over the decades is confirmed in candid interviews with performers. The content of the book is based on archival sources, letters, memoirs, interviews and stories told inside the opera house. Juhani Koivisto, the Opera’s chief dramaturge, clearly has an excellent inside knowledge of his subject. Translated by Ruth Urbom

Speaking with silence

26 September 2013 | Reviews

Bo Carpelan. Photo: Charlotta Boucht / Schildts & Söderströms

Bo Carpelan

Mot natten

[Towards the night. Poems 2010]

Helsinki: Schildts & Söderströms, 2013. 69 p.

ISBN 978-951-52-32-20-5

€21, paperback

‘Don’t change, grow deeper ,’ wrote Bo Carpelan: over the years he broadened his poetic range and his personal idiom evolved, but it happened organically, without sudden upheavals of style or idea.

Mot natten (‘Towards the night’) is Carpelan’s last collection of poems. This is underlined by the book’s subtitle, Poems 2010. By then Carpelan (1926–2011) was already marked by the illness that took his life in early 2011. It doesn’t show in the quality of the poems, but knowing it may make it harder for the reader to approach them with unclouded eyes. When a great poet concludes his work one wants to seek a synthesis or a concluding message, and that may encumber one’s reading. So is there such a message? In some ways there is, but Carpelan was not a man of pointed formulations. His ideals emerged without much fuss. More…

Hare-raising

13 February 2015 | Reviews

In this job, it’s a heart-lifting moment when you spot a new Finnish novel diplayed in prime position on a London bookshop table – and we’ve seen Tuomas Kyrö’s The Beggar & The Hare in not just one bookshop, but many. Popular among booksellers, then – and we’re guessing, readers – the book nevertheless seems in general to have remained beneath the radar of the critics and can therefore be termed a real word-of-mouth success. Kyrö (born 1974), a writer and cartoonist, is the author of the wildly popular Mielensäpahoittaja (‘Taking umbridge’) novels, about an 80-year-old curmudgeon who grumbles about practically everything. His new book – a story about a man and his rabbit, a satire of contemporary Finland – seems to found a warm welcome in Britain. Stephen Chan dissects its charm

Tuomas Kyrö: The Beggar & The Hare

Tuomas Kyrö: The Beggar & The Hare

(translated by David McDuff. London: Short Books, 2011)

Kerjäläinen ja jänis (Helsinki: Siltala, 2011)

For someone who is not Finnish, but who has had a love affair with the country – not its beauties but its idiosyncratic masochisms; its melancholia and its perpetual silences; its concocted mythologies and histories; its one great composer, Sibelius, and its one great architect, Aalto; and the fact that Sibelius’s Finlandia, written for a country of snow and frozen lakes, should become the national anthem of the doomed state of Biafra, with thousands of doomed soldiers marching to its strains under the African sun – this book and its idiots and idiocies seemed to sum up everything about a country that can be profoundly moving, and profoundly stupid.

It’s an idiot book; its closest cousin is Voltaire’s Candide (1759). But, whereas Candide was both a comedic satire and a critique of the German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), The Beggar & The Hare is merely an insider’s self-satire. Someone who has not spent time in Finland would have no idea how to imagine the events of this book. Candide, too, deployed a foil for its eponymous hero, and that was Pangloss, the philosopher Leibniz himself in thin disguise. Together they traverse alien geographies and cultures, each given dimension by the other. More…