Search results for "kjell west"

What Finland read in August

12 September 2013 | In the news

Cantharellus cibarius: very edible. Photo: Wikimedia/Andreas Kunze

The August list of best-selling fiction and non-fiction, compiled by the Finnish Booksellers’ Association, features thrillers, new Finnish fiction, dictionaries and diet guides.

Number one of the Finnish fiction list was a new crime novel by Leena Lehtolainen, Rautakolmio (‘The iron triangle’, Tammi). The new novel, Hägring (‘Mirage’, Schildts & Söderströms; in Finnish, Kangastus, Otava), by Kjell Westö, was number two; in third place was Aapine, an ABC-book written in the south-western dialect by poet and author Heli Laaksonen and illustrated by Elina Warsta (Otava).

The list of translated fiction included – not surprisingly – names like Dan Brown, Jon Nesbø, Camilla Läckberg, Charlaine Harris and Henning Mankell.

5:2 dieetti (The Fast Diet), by Michael Mosley and Mimi Spencer, sold like hot cakes – the Finns are statistically the fattest people in Scandinavia – and was number one on the non-fiction list. There were also several dictionaries (four of them Finnish-English-Finnish) as well as a field guide to mushrooms, of which there are plenty in the woods this early autumn. It is indeed essential to be able to tell the Poisonpie and the Sickener from the real deliciacies.

Finlands svenska litteratur 1900–2012 [Finland’s Swedish literature 1900–2012]

6 November 2014 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Finlands svenska litteratur 1900–2012

Finlands svenska litteratur 1900–2012

[Finland’s Swedish literature 1900–2012]

Red. [Edited by] Michel Ekman

Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland / Stockholm: Atlantis, 2014. 376 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-951-583-272-6

€35.90, paperback

This history of Finland-Swedish literature is an updated version of the second volume of Finlands svenska litteraturhistoria (eds. Johan Wrede and Clas Zilliacus, 1999–2000), and it concentrates on the period from 1900 to 2012, with much new critical material relating to the years after 1975. Some 20 contributors under the editorship of Michel Ekman provide a diverse and inclusive overview of a literature that embraces poetry, prose fiction, children’s writing, essays and drama. The book traces the story of Finland-Swedish literature from the ‘fresh start’ of the turn of the 19th century, through the experiments of modernists like the poets Edith Södergran and Elmer Diktonius, to the work of present-day novelists like Monika Fagerholm and Kjell Westö. However, the emphasis throughout is on general lines of development rather than on individual authors’ careers. The authors discuss the relationship between the work of Finland’s Swedish-language writers and their Finnish-language counterparts in a perspective that not only views the minority literature as a part of the Finnish whole, but also considers it as a bridge between the literatures of Sweden and Finland – the subject of a concluding essay by Clas Zilliacus. The material is presented in essays subdivided in a readable way that combines factual information with critical and historical analysis.

Seekers and givers of meaning: what the writer said

2 October 2014 | This 'n' that

‘All our tales, stories, and creative endeavours are stories about ourselves. We repeat the same tale throughout our lives, from the cradle to the grave.’ CA

‘All our tales, stories, and creative endeavours are stories about ourselves. We repeat the same tale throughout our lives, from the cradle to the grave.’ CA

‘Throughout a work’s journey, the writer filters meanings from the fog of symbols and connects things to one another in new ways. Thus, the writer is both a seeker of meaning and a giver of meaning.’ OJ

‘Words are behind locks and the key is lost. No one can seek out another uncritically except in poetry and love. When this happens the doors have opened by themselves.’ EK

‘I realised that I had to have the courage to write my kind of books, not books excessively quoting postmodern French philosophers, even if that meant laying myself open to accusations of nostalgia and sentimentality.’ KW

‘If we look at the writing process as consisting of three C:s – Craft, Creativity and Chaos – each one of them is in its way indispensable, but I would definitely go for chaos, for in chaos lies vision.’ MF

‘In the historical novel the line between the real and the imagined wavers like torchlight on a wall. The merging of fantasy and reality is one of the essential features of the historical novel.’ KU

‘The writer’s block isn’t emptiness. It’s more like a din inside your head, the screams of shame and fear and self-hatred echoing against one another. What right have I to have written anything in the first place? I have nothing to say!’ PT

‘…sometimes stanzas have to / assume the torch-bearer’s role – one / often avoided like the plague. / Resilient and infrangible, the lines have to / get on with their work, like a termite queen / laying an egg every three seconds / for twenty years, / leaving a human to notice / their integrity. ’ JI

In 2007 when Books from Finland was a printed journal, we began a series entitled On writing and not writing; in it, Finnish authors ponder the complexities, pros and cons of their profession. Now our digitised archives make these writings available to our online readers: how do Claes Andersson, Olli Jalonen, Eeva Kilpi, Kjell Westö, Monika Fagerholm, Kaari Utrio, Petri Tamminen and Jouni Inkala describe the process? Pain must coexist with pleasure…

From 2009 – when Books from Finland became an online journal – more writers have made their contributions: Alexandra Salmela, Susanne Ringell, Jyrki Kiiskinen, Johanna Sinisalo, Markku Pääskynen, Ilpo Tiihonen, Kristina Carlson, Tuomas Kyrö, Sirpa Kähkönen – the next, shortly, will be Jari Järvelä.

The books that sold in December

9 January 2014 | In the news

It seems that the Finlandia Prize does, as intended, have a strong influence in book sales. In December, a novel about the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva by Riikka Pelo, Jokapäiväinen elämämme (’Our everyday life’), which won the fiction prize in December, reached number one on the list of best-selling Finnish fiction.

It seems that the Finlandia Prize does, as intended, have a strong influence in book sales. In December, a novel about the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva by Riikka Pelo, Jokapäiväinen elämämme (’Our everyday life’), which won the fiction prize in December, reached number one on the list of best-selling Finnish fiction.

The next four books on the list – compiled by the Finnish Booksellers’ Association – were the latest thriller by Ilkka Remes, Omertan liitto (‘The Omerta union’), a novel Me, keisarinna (‘We, the tsarina’), about the Russian empress Catherine the Great by Laila Hirvisaari, a novel, Hägring 38 (‘Mirage 38’), by Kjell Westö, and a novel, Kunkku (‘The king’), by Tuomas Kyrö.

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction, Murtuneet mielet (‘Broken minds’), about the mentally crippled Finnish soldiers in the Second World War, also did well: it was number two on the non-fiction list. (Number one was a book about a Finnish actor and television presenter, Ville Haapasalo, who trained at the theatre academy in St Petersburg and became a film star in Russia.)

The ten best-selling books for children and young people were all Finnish (and written in Finnish): it seems that this time the buyers of Christmas presents favoured books written by Finnish authors.

Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2013

14 November 2013 | In the news

One of the following six novels will be awarded this year’s Finlandia Prize for Fiction, worth 30,000 euros: Ystäväni Rasputin (’My friend Rasputin’) by JP Koskinen, Hotel Sapiens (Teos) by Leena Krohn, Jokapäiväinen elämämme (‘Our everyday life’, Teos) by Riikka Pelo, Terminaali (‘The terminal’, Siltala) by Hannu Raittila, Herodes (‘Herod’, WSOY) by Asko Sahlberg and Hägring 38 (‘Mirage 38’, Schildts & Söderströms; Finnish translation, Kangastus, Otava) by Kjell Westö.

Half of the writers have already won the Finlandia Prize once, namely Krohn (1992), Raittila (2001) and Westö (2006).

Four of the six works deal with a historical character or history: Koskinen with the Russian ‘holy man’ Rasputin, Pelo with the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva, Sahlberg with Herod the Great of Judea. Westö goes back to the year 1938 in Finland.

Raittila’s realistic novel takes place on contemporary airports. Krohn, again taking a look at an unknown future, presents the reader with a imaginary Earth which no longer is habitable to humans.

The runners-up were chosen by a jury – appointed by the Finnish Book Publishers’ Association – of three: the journalists Nina Paavolainen and Raisa Rauhamaa and the translator Juhani Lindholm. The winner of the 30th Finlandia Prize for Fiction will chosen by theatre manager of the Helsinki City Theatre and actor Asko Sarkola, and announced on 3 December.

Worlds apart

18 June 2009 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Helsinki boys by the sea: in Martti Jämsä’s Polaroid lads play on the beach; in I.K. Inha’s photograph (Hietalahden satama, ‘Hietalahti harbour’), taken a century earlier, barefoot urchins meet up on the quayside

A hundred years ago the photographer I.K. Inha (1865–1930) was asked to illustrate a tourist guide to Helsinki. He took some 200 photographs, of which some 60 were included in the book, which was published by WSOY in 1910. In his new book of photographs, OPS! Helsinki Polaroid¹, Martti Jämsä (born 1959), wanders the same streets a century on, taking snapshots with his Polaroid camera. More…

A new publishing company – and old

23 December 2011 | In the news

In the early months of 2012 Finland’s two old and time-honoured Swedish-language publishers, Schildts and Söderströms, will merge.

Söderströms will buy Schildts, whose owners (two non-profit associations, Svenska folkskolans vänner and Finlands svenska lärarförbund) will acquire a nearly 20 per cent share in the new company. The largest share in Schildts & Söderströms will be held by the art association Konstsamfundet (24 per cent), while the company’s third major owner will be Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland (15 per cent).

Both publishers have been operating with a loss in turnover of approximately half a million euros, though at the same time investment capital has brought them almost the same amount. Textbook publishing has been profitable for both, while general literature has been published at a loss.

With a turnover of slightly over six million euros, the new Schildts & Söderströms will employ a workforce of nearly 50.

Holger Schildt founded the Finnish-Swedish publishing house of Schildts in 1913. Its most internationally famous and best-selling fiction writer is the mother of the Moomins, Tove Jansson (1914–2001). Edith Södergran, Runar Schildt, Bo Carpelan and Robert Åsbacka are, for example, Schildts’ authors.

Holger Schildt founded the Finnish-Swedish publishing house of Schildts in 1913. Its most internationally famous and best-selling fiction writer is the mother of the Moomins, Tove Jansson (1914–2001). Edith Södergran, Runar Schildt, Bo Carpelan and Robert Åsbacka are, for example, Schildts’ authors.

Werner Söderström founded the company that bears his name in 1878. Now known as WSOY, it originally published both Finnish and Swedish-language literature; the firm of Söderström & Co. was founded in 1891 for the exclusive publishing of Swedish-language literature. Söderström’s authors have included Gunnar Björling, Jörn Donner, Monika Fagerholm and Kjell Westö, among others.

Werner Söderström founded the company that bears his name in 1878. Now known as WSOY, it originally published both Finnish and Swedish-language literature; the firm of Söderström & Co. was founded in 1891 for the exclusive publishing of Swedish-language literature. Söderström’s authors have included Gunnar Björling, Jörn Donner, Monika Fagerholm and Kjell Westö, among others.

It is thought that the merger may lead to a reduction in the number of fiction and poetry titles published – but there are also hopes that there may be an improvement in their quality.

Men and a woman, too

7 November 2009 | This 'n' that

In October, according to the best-seller list (Mitä Suomi lukee, ‘What Finland reads’), the top seven non-fiction titles included biographies of four Finns – an industrial tycoon (Pekka Herlin, one-time director of the Finnish Kone elevator company), a poet (Paavo Haavikko), and a former Prime Minister (Paavo Lipponen).

In October, according to the best-seller list (Mitä Suomi lukee, ‘What Finland reads’), the top seven non-fiction titles included biographies of four Finns – an industrial tycoon (Pekka Herlin, one-time director of the Finnish Kone elevator company), a poet (Paavo Haavikko), and a former Prime Minister (Paavo Lipponen).

The seventh place was held by a book on a woman: Lenita Airisto, winner of a 1950s beauty contest, later a television hostess, celebrity, writer and businesswoman (Lähikuvassa Lenita Airisto, ‘Lenita Airisto in closeup’, by Juha Numminen).

The Finnish fiction list was topped by the latest thriller by Ilkka Remes, Isku ytimeen (‘Strike to the core’). Then came Kjell Westö’s novel Älä käy yöhön yksin (‘Don’t go out into the night alone’, a translation of the Swedish-language original, Gå inte ensam ut i natten) and Jari Tervo’s Koljatti (‘Goliath’). The latest Henning Mankell was number one on the translated fiction list.

Thrills and spills

23 October 2009 | This 'n' that

In September the comic strip Viivi & Wagner by Juba, number two in August on the list of best-selling books (Mitä Suomi lukee, ‘What Finland reads’ – in Finnish only), gave way to Jari Tervo’s political satire Koljatti (‘Goliath’) and to a new thriller by Ilkka Remes (Isku ytimeen, ‘Strike to the core’).

Number three was Kjell Westö’s novel Älä käy yöhön yksin (in Finnish; the original, Gå inte ensam ut i natten, was published in Swedish, Westö’s mother tongue; ‘Don’t go out into the night alone’) and number four Kari Hotakainen’s novel Ihmisen osa (‘The human condition’).

Numbers eight and nine were new thrillers / crime novels by Leena Lehtolainen and Matti Rönkä. Historical novels by Kaari Utrio and Laila Hirvisaari took the fifth and sixth places.

Not surprisingly, the international bestsellers Paulo Coelho, Henning Mankell, Donna Leon and Patricia Cornwell led the translated fiction list.

As for non-fiction, the doings of Finnish Security Police interests people greatly: a history of it from 1949 to 2009 (edited by Matti Simola), entitled Ratakatu 12 (‘Ratakatu street 12’, WSOY) made its way to the top. It was followed by a biography of the industrial magnate Pekka Herlin of the Kone elevator company, Koneen ruhtinas (‘The prince of Kone’) – and Hitler by Ian Kershaw.

The search goes on

31 December 2007 | Archives online, Essays, On writing and not writing

The Finlandia Prize-winning author Kjell Westö recalls his literary adolescence, and the moment – of a dark January night – when he stopped worrying about writer’s block and began to write

When I was in my twenties, my urge to write was very strong. I was driven, almost consumed, by this ever-present zeal, which tore me apart nearly as inexorably and effectively as love did. But I wrote precious little. Now, some twenty years later, I have a general idea about the traps I so unknowingly walked into. More…

The Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2013

5 December 2013 | In the news

Riikka Pelo. Photo: Heini Lehväslaiho

The director general of the Helsinki City Theatre, Asko Sarkola, announced the winner of the 30th Finlandia Literature Prize for Fiction, chosen from a shortlist of six novels, on 2 December in Helsinki. The prize, worth €30,000, was awarded to Riikka Pelo for her novel Jokapäiväinen elämämme (‘Our everyday life’, Teos).

In his award speech Sarkola – and actor by training – characterised the six novels as ‘six different roles’:

‘They are united by a bold and deep understanding of individuality and humanity against the surrounding period. They are the perspectives of fictive individuals, new interpretations of the reality we imagine or suppose. Viewfinders on the present, warnings of the future.

‘Riikka Pelo‘s Jokapäiväinen elämämme is wound around two periods and places, Czechoslovakia in 1923 and the Soviet Union in 1939–41. The central characters are the poet Marina Tsvetaeva and her daughter Alya. This novel has the widest scope: from stream of consciousness to interrogations in torture chambers and the labour camps of Vorkuta; always moving, heart-stopping, irrespective of the settings.’

The five other novels were Ystäväni Rasputin (’My friend Rasputin’) by JP Koskinen, Hotel Sapiens (Teos) by Leena Krohn, Terminaali (‘The terminal’, Siltala) by Hannu Raittila, Herodes (‘Herod’, WSOY) by Asko Sahlberg and Hägring 38 (‘Mirage 38’, Schildts & Söderströms; Finnish translation, Kangastus, Otava) by Kjell Westö (see In the news for brief features).

Landscape

30 June 2006 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

(Landskap, 1919). Introduction by Juha Virkkunen

12 March

To begin with, there’s a great white field. The field is criss-crossed with low slender fences and little patches of yellow-green stubble peering up through the snow, and hare-tracks slanting away towards the stubble. But we won’t notice the fences and the stubble and the hare tracks. Because we’re going to take a wider, more sort of decorative view.

So we see the great white field. And where the field ends a dark green screen has been drawn. The screen has been cut short rather amusingly in the middle, so one can see yet another white held. This belongs to another village. And this other village itself has crept up timidly to the forest-clad hill and lies close to it, so we don’t notice this other village. Because we want to take a wider view of things. More…

Do you speak my language?

23 August 2012 | Articles, Non-fiction

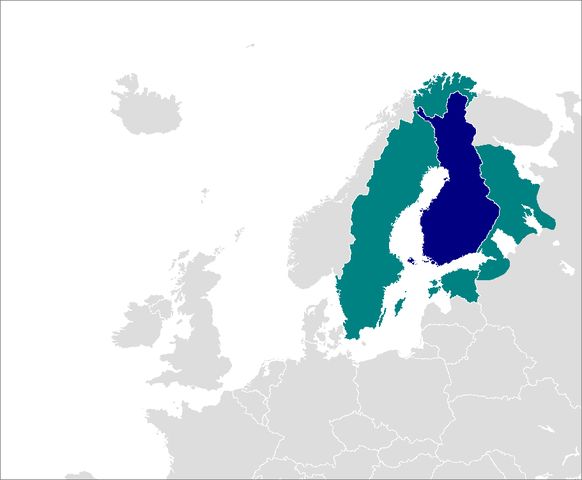

Finnish spoken outside Finland: Sweden (west), Estonia (south), Karelia/Russia (east), Norway (north). Illustration: Zakuragi/Wikipedia

Finland has two official languages, Finnish and Swedish. Approximately five per cent of the population (290,000 Finns) speak Swedish as their native language. All Finns learn both languages at school, and students in higher education must prove they have an adequate knowledge of the other mother tongue. But how do native speakers of Finnish cope with what is, for many of them, a minority language that they will never need or even wish to use? We take a look at bilingual issues – and a new book devoted to them

‘In many parts of the world, language can be a fiery and divisive issue, one that pits the powerless against the powerful, the small against the big. The Basques battle the Spanish. The Flemish tussle with the Walloons. The Québécois scuffle with the rest of Canada.’

That is how Lizette Alvarez illustrated her theme in her article ‘Finland Makes Its Swedes Feel at Home’, published in the New York Times in 2005.

In Finland, language has been a fiery issue at times, though things have cooled down a bit since the early 20th century. The use of Finnish as a written language dates back to the 16th century, but the territory of Finland was part of the Swedish Empire until 1809. Swedish was spoken by the nobility as well as most of the peasant class – the mechanism of the state did not serve Finnish-speaking peasants or other segments of the population in Finnish. More…

Tuva Korsström

Tuva Korsström