Search results for "moomins/feed/www.booksfromfinland.fi/2014/10/letters-from-tove"

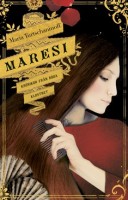

Maria Turtschaninoff: Maresi. Krönikor från röda klostret [Maresi. Chronicles of the red convent]

6 March 2015 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Maresi. Krönikor från röda klostret

Maresi. Krönikor från röda klostret

[Maresi. Chronicles of the red convent]

Helsinki: Schildts & Söderströms, 2014. 213 pp.

ISBN 978-951-52-3471-1

€18.90, hardback

Maresi. Punaisen luostarin kronikoita

Suom. [Translated from Swedish into Finnish by]: Marja Kyrö

Helsinki: Tammi, 2014. 213 pp.

ISBN 978-951-31-8000-3

€25.90, hardback

Maria Turtschaninoff (born 1971) has quickly established a place as a leading author of Finland-Swedish young adults’ literature. Her fantasy novel Maresi is set in an old convent run entirely by women. The narrator Maresi is a conscientious girl loved by the congregation of sisters; she is gradually learning of her own special talents and what is expected from her. The peace of the convent is threatened with the arrival of the mute, uncommunicative Jai. Her experience of trauma gradually come to light and the girls work up their collective courage, together with the other women, to challenge the despotism of men. Turtschaninoff is a visual storyteller; her descriptions of nature, convent life, and animal care are indelible. The setting is vividly drawn and the sheltered environment feels well depicted. The novel unflinchingly takes on women’s experiences of physical and psychological violence, and its points of identification transcend all cultural boundaries. This provocative, feminist novel won the 2014 Finlandia Junior prize.

Translated by Lola Rogers

Love is the only song

7 August 2014 | Fiction, poetry

Poems from Helise, taivas! Valitut runot (‘Ring out, sky! Selected poems’, Siltala, 2014). Introduction by Marja-Leena Mikkola

Who will tell me?

Who will tell me why white butterflies

strew the velvet skin of the night?

Who will tell me?

While people walk, mute and strange

and they have snowy, armoured faces,

such snowy faces!

and the eyes of a stuffed bird.

Who will tell me why in the morning, on the grass,

the thrushes begin their secret game?

Who will tell me?

While black soldiers stand at the gate

in their hands withered roses

such withered roses!

and broken tiger lilies.

Who will tell me, quietly in the sun’s shadow

how to bare my heart?

Who will tell me?

Come to me over the fields

Come close and softly

so softly!

Open the clothes of my heart. More…

Helene Schjerfbeck. Och jag målar ändå [Helene Schjerfbeck. And I still paint]

16 December 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Helene Schjerfbeck. Och jag målar ändå. Brev till Maria Wiik 1907–1928

Helene Schjerfbeck. Och jag målar ändå. Brev till Maria Wiik 1907–1928

[Helene Schjerfbeck. And I still paint. Letters to Maria Wiik 1907–1928]

Utgivna av [Edited by]: Lena Holger

Helsingfors: Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland; Stockholm: Bokförlaget Atlantis, 2011. 301 p., ill.

ISBN (Finland) 978-951-583-233-7

ISBN (Sweden) 978-91-7353-524-3

€ 44, hardback

In Finnish:

Helene Schjerfbeck. Silti minä maalaan. Taiteilijan kirjeitä

[Helene Schjerfbeck. And I still paint. Letters from the artist]

Toimittanut [Edited by]: Lena Holger

Suomennos [Translated by]: Laura Jänisniemi

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2011. 300 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-305-0

€ 44, hardback

This work contains a half of the collection of some 200 letters (owned by the Signe and Ane Gyllenberg’s foundation), until now unpublished, from artist Helene Schjerfbeck (1862–1946) to her artist friend Maria Wiik (1853–1928), dating from 1907 to 1928. They are selected and commented by the Swedish art historian Lena Holger. Schjerfbeck lived most of her life with her mother in two small towns, Hyvinge (in Finnish, Hyvinge) and Ekenäs (Tammisaari), from 1902 to 1938, mainly poor and often ill. In her youth Schjerfbeck was able to travel in Europe, but after moving to Hyvinge it took her 15 years to visit Helsinki again. In these letters she writes vividly about art and her painting, as well as about her isolated everyday life. Despite often very difficult circumstances, she never gave up her ambitions and high standards. Her brilliant, amazing, extensive series of self-portraits are today among the most sought-after north European paintings; she herself stayed mostly poor all her long life. The book is richly illustrated with Schjerfbeck’s paintings (mainly from the period), drawings and photographs.

Dead calm

31 December 2007 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel En lycklig liten ö (‘A happy little island’, Söderströms, 2007)

In the beginning the computer screen was without form, and void, and the scribe’s fingers rested on the keyboard.

The scribe bit his lower lip. His gaze travelled like a fly from the workroom’s crowded bookshelves to the rocking chair in front of the window and the coloured prints of birds on the walls. He went out into the kitchen and drank some water. Then he sat down in front of the computer again.

To create from nothing a fictitious world assisted only by the tools language places at our disposal, surely that must be a great and exacting undertaking!

The scribe hesitated and racked his brains for a long time before finally typing the first word: ‘sky’. Then after long thought he typed another word: ‘sea’. More…

The life of a lonely friend

30 September 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Bo Carpelan. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

Extracts from Bo Carpelan‘s novel Axel, ‘a fictional memoir’ (1986). In his preface to the novel Bo explains how he ‘found’ Axel.

Preface

In the 1930s I came across the name of Axel Carpelan (1858-1919), my paternal grandfather’s brother, in Karl Ekman’s Jean Sibelius and His Work (1935). In the bibliography, the author briefly mentions quotes from letters in the book addressed to Axel Carpelan, ‘who belonged to the Master’s most intimate circle of friends, and in musical matters was his constant confidant. Sibelius commemorated their friendship by dedicating his second symphony to him’. I had never heard Axel’s name mentioned in my own family.

Many years after Karl Ekman, the original incentive for the novel about Axel arose through Erik Tawaststjerna’s biography of Sibelius, in which Axel is portrayed in the second volume (1967) of the Finnish edition, and whose life came to an end in Part IV (1978). From early 1970s onwards, I started notes for Axel’s fictional diary from to 1919. It is not known whether Axel himself ever kept a diary. I relied as muchas possible on all the available facts. These increased when I was given access to letters exchanged between Axel and Janne from the year 1900 onwards. It became the story of the hidden strength a very lonely and sick man, and of a friendship in which the give and take both sides was far greater than Axel himself could ever have imagined.

Hagalund, June 1st, 1985

Bo Carpelan

![]()

1878, Axel’s diary

15.1.

On my twentieth birthday, I remember the young Wolfgang; ‘Little Wolfgang has no time to write because he has nothing to do. He wanders up and down the room like a dog troubled by flies’. However, that dog achieved a paradise. I have learnt yet one more piece of wisdom: ‘It is my habit to treat people as I find them; that is the most rewarding in the long run’. More…

Mother-days

30 June 2006 | Fiction, poetry

Poems from Yhtä juhlaa (‘It’s all a big celebration’, WSOY, 2006)

(a square metre, 3.)

Now for the-kick-of-being-the-good-mum:

after the rye porridge

after the sons washed with camomile foam

and slipped into clean sheets

with mummy singing a sweet song.

Something about shadowed snow

and how at the blue twilit-moment one can

go inwards. If you’re up to looking. All that garbage and slag:

ash from the too-small days, clotted with

non-combustible blots, even though here

the sky’s clear

and the windows open to the winds.

Good grief, here we’re making new people.

But all I’d time for

was the track from the dishcloth to the nappy bin,

and back from the children’s painting-table

to the sink. No job

for spoilt girls, this: the prissiest minx

would soon turn woman in this fix:

kids coming next after next,

years of full-time labour

in a square metre where

you make no point about peccadilloes,

because so much is at stake.

You’re no longer a rose,

pimpinella, rosabella,

but subsoil: loam

and spots of unrottable compost.

A feebler person would have reversed on

the first tantrum;

the child’s learnt to say things

and is saying things

I never thought would come. More…

Boys Own, Girls Own? –

Gender, sex and identity

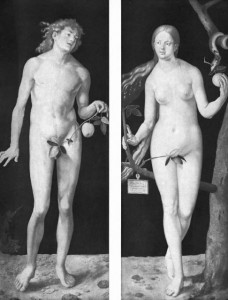

30 December 2008 | Essays, Non-fiction

Knowing good and evil: Adam and Eve (Albrecht Dürer, 1507)

In Finnish fiction of the present decade, both in poetry and in prose, there seems to be at least one principle that cuts across all genres: an overt expression of gender, writes the critic Mervi Kantokorpi in her essay

Relationships and family have always been central concerns of literature; questions about gender and individual identity have received a new emphasis in Finnish literature from one season to the next. The gender roles represented in contemporary literature appear to become ever more stereotypical. The question is no longer only of the author consciously setting his or her gender up as the starting point for expression, as has already long been the case with modern literature written by women. More…

Rock or baroque?

30 April 2014 | Extracts, Non-fiction

What if your old favourites lose their flavour? Could there be a way of broadening one’s views? Scholar Olli Löytty began thinking that there might be more to music than 1980s rock, so he turned to the music writer Minna Lindgren who was delighted by the chance of introducing him the enormous garden of classical music. In their correspondence they discussed – and argued about – the creativity of orchestra musicians, the significance of rhythm and whether the emotional approach to music might not be the only one. Their letters, from 2009 to 2013, an entertaining musical conversation, became a book. Extracts from Sinfoniaanisin terveisin. Kirjekurssi klassisen musiikin maailmaan (‘With symphonical greetings. A correspondence course in classical music’)

What if your old favourites lose their flavour? Could there be a way of broadening one’s views? Scholar Olli Löytty began thinking that there might be more to music than 1980s rock, so he turned to the music writer Minna Lindgren who was delighted by the chance of introducing him the enormous garden of classical music. In their correspondence they discussed – and argued about – the creativity of orchestra musicians, the significance of rhythm and whether the emotional approach to music might not be the only one. Their letters, from 2009 to 2013, an entertaining musical conversation, became a book. Extracts from Sinfoniaanisin terveisin. Kirjekurssi klassisen musiikin maailmaan (‘With symphonical greetings. A correspondence course in classical music’)

Olli, 19 March, 2009

Dear expert,

I never imagined that the day would come when I would say that rock had begun to sound rather boring. There are seldom, any more, the moments when some piece sweeps you away and makes you want to listen to more of the same. I derive my greatest enjoyment from the favourites of my youth, and that is, I think, rather alarming, as I consider people to be naturally curious beings whom new experiences, extending their range of experiences and sensations, brings nothing but good.

Singing along, with practised wistfulness, to Eppu Normaali’s ‘Murheellisten laulujen maa’ (‘The land of sad songs’) alone in the car doesn’t provide much in the way of inspiration. It really is time to find something new to listen to! My situation is already so desperate that I am prepared to seek musical stimulation from as distant a world as classical music. I know more about the African roots of rock than about the birth of western music, the music that is known as classical. But it looks and sounds like such an unapproachable culture that I badly need help on my voyage of exploration. Where should I start, when I don’t really know anything? More…