Search results for "david barrett"

Plain sailing

31 March 1996 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Alastalon salissa (‘In Alastalo’s parlour’, 1933). Introduction by Kai Laitinen

A letter from the translator:

Dear Editors,

Reluctantly (I really have tried) I have been driven to conclude that Alastalon salissa is untranslatable, except perhaps by a fanatical Volter Kilpi enthusiast who is prepared to devote a lifetime to it. To mention only one of the difficulties, there is no English equivalent to the style of the Finnish ‘proverbs’ (real or imaginary) with which the main character Alastalo’s thoughts are so thickly larded. Add to this the richness and, yes, eccentricity, of Kilpi’s vocabulary, and the unfamiliarity of much of the subject-matter, centred as it is on the interests of a sea going community that hardly exists any longer, even on the islands, and you have a text that is full of pitfalls for the translator. As for the humour, I’m sorry to say that it depends so much on the idiom and presentation that it doesn’t come over at all. If I did any more, I’m afraid it would just have to be a laborious paraphrase, and I don’t think I’m capable of making it effective, or even readable, in English.

Apart from that, although I’m very grateful for your explanations of the many unfamiliar words and phrases, I’m very unwilling to commit myself to the translation of any of them on the basis of a mere ‘gloss’ (technical word): I need to know the associations, and possible sound-echoes, of every one of them before I can be sure of getting it right. And getting it right affects the rhythm of every sentence: it’s not just a matter of filling in blanks with ‘equivalents’ provided by someone else.

I’ve no objection to your using my version of the opening pages. If you decide to follow it with some kind of comment, do borrow, if you need to, from my remarks above, giving the translator’s point of view. Sorry to have failed you so badly.

Yours, David Barrett More…

‘Joy and peace prevail…’

25 December 2010 | Fiction, Prose

Dear readers,

to celebrate the change of the year we publish an extract from Aleksis Kivi’s 1870 classic novel, Seitsemän veljestä (Seven Brothers), translated by David Barrett, and a bit of a classic of our own too: it’s a nostalgic glimpse of a Finnish Christmas spent in a humble cottage inhabited, in addition to the eponymous seven brothers, a horse, cat, cockerel and two dogs (at least). Enjoy!

Soila Lehtonen & Hildi Hawkins & Leena Lahti

On a festive night

It is Christmas Eve. The weather has been mild, grey clouds fill the sky, hills and valleys are covered with the snow that has only recently begun to fall. The forest gives out a gentle murmur, the grouse goes to roost in the catkined birch, a flock of waxwings descends on the reddening rowan, while the magpie, daughter of the pine-wood, carries twigs for her future nest. More…

New from the archive

26 March 2015 | This 'n' that

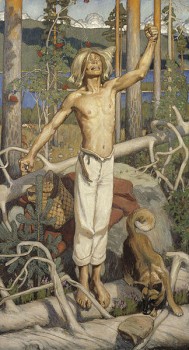

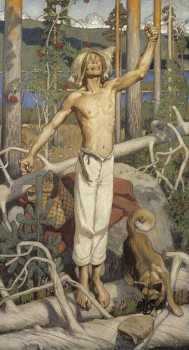

Kullervo’s curse. Painting by Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1899)

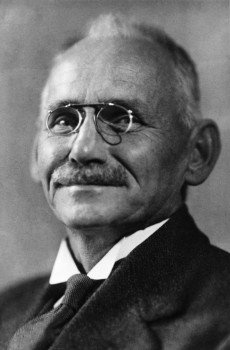

Finland’s national epic adapted for the stage by Finland’s national writer: best known as the author of the first significant novel in Finnish, Seitsemän veljestä (Seven Brothers, 1870), Aleksis Kivi (1834-1972) also turned one of the Kalevala’s grimmest stories, that of Kullervo – a tale of incest, revenge and death– into a five-act tragedy.

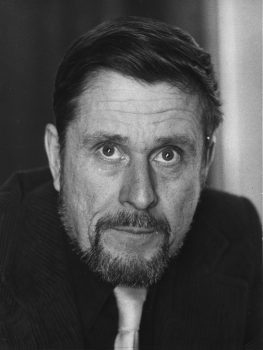

The translation is by one of Books from Finland’s most long-standing collaborators, David Barrett (1914-1998), a true linguistic genius with a speciality in Georgian as well as Finnish in addition to classical Greek; as well as his work with texts in Finnish and Georgian, he made extensive translations of Aristophanes for Penguin Classics. Barrett felt, as he argues here in his introduction, ‘that Kullervo, if suitably translated, might succeed where Seven Brothers had failed, in bringing Kivi’s genius to the notice of the English-speaking world’.

Was he right? It is up to you, dear readers, to judge.

For a very different, demythologized, view of the Kullervo story, we also publish a manuscript by the modernist poet Paavo Haavikko (1931-2008) from his television adaptation Rauta-aika (‘Age of iron’, 1982).

The Kalevala is in development as a film by the Finnish entertainment company Rovio, of Angry Birds game, and the Finnish-born video game company Supercell. It remains to be seen how the Kalevala take to the big screen.

*

The digitisation of Books from Finland continues, with a total of 372 articles and book extracts made available online so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

Encounters with a language

12 December 2014 | Articles, Non-fiction

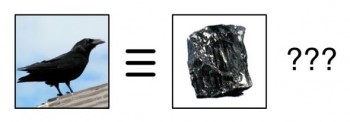

Mistranslation: illustration by Sminthopsis84/Wikimedia

Mother tongue: not Finnish. How do people become interested enough in the Finnish language in order to become translators? In the olden days some might have been greatly inspired by the music Sibelius (as were the eminent British translators of Finnish, David Barrett or Herbert Lomas, for example, back in the 1950s and 1960s). We asked contemporary translators to reminisce on how they in turn have become infatuated enough with Finnish to start studying and translating this small, somewhat eccentric northern language. Three translators into English, one into French, German and Latvian tell us why

The Last War Hero

31 March 1981 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from 30-åriga kriget (‘The Thirty Years’ War’). Introduction by Markku Envall

First he heard the noise.

It was an unfamiliar noise and therefore doubly dangerous. Viktor grabbed his machine-pistol. It was a sputtering noise, like that of a cracked machine-gun. But it came from above. And what came from above could be dangerous, Viktor knew.

Then he saw the helicopter, flying just above the tree-tops. He had never seen a helicopter before. Nor had he ever seen the circular markings carried by the aircraft as a sign of the nationality. More and more nations were getting involved, he had had a visit from an American, for all he knew this might be a plane from Australia. The Russians must be in a tight corner if they had to keep sending their allies into the firing line.

He bitterly regretted having let the American sergeant get away.

Now they were after him in real earnest. It must have been the Yankee who had sent them.

Viktor directed a long burst of fire at the plane, which was now hovering almost motionless in the air, like a bee over a flower. The bullets shattered the roboter blades, splinters flew in all directions, and the helicopter dived at a steep angle and plunged into the lake. Viktor leapt to his feet and shouted “Hurrah!” and proceeded to execute a gleeful victory dance. He had shot down an enemy aircraft. More…

The Onlookers

30 September 1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Naisten vuonna (‘In women’s year’, 1975). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

The two elks came out on to the road through a gap between timber sheds. They began to cross the road, and the larger one was very nearly run into by a car. Cars stopped and horns tooted, till the elks turned and made off towards the harbour. Several cars swung round and drove along the cinder track in pursuit of the animals.

The elks headed across the rubble towards the power station; after circling some stacks of railway sleepers, they ended up on the flank of a coalheap sixty feet high. The cars pulled up and their occupants poured out, shouting that the elks wouldn’t go that way, it was a dead end. The elder of the two elks had indeed sensed this, and they moved off to the right, skirting the coal-heap and emerging among the timber-stacks. By this time the first cyclists and pedestrians had arrived on the scene.

“They’ll break their legs,” said a pedestrian to a motorist. “There’s all kinds of junk lying about.” More…

Human Freedom

30 June 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Mika Waltari. Photo: SKS Archives

Extract from lhmisen vapaus (‘Human Freedom’, 1950)

‘Where are we?’ Yvonne asked. ‘This isn’t the right street either. Somewhere between Alma and Georges V, they said. But there’s no sign of an aquarium.’

‘Talking of aquariums’, I suggested, ‘there’s a dog shop near here where they wash dogs in the back room. If you like, I’ll take you to see how they wash a dog. It’s a very soothing experience.’

‘You’re crazy’, said Yvonne.

My feelings were hurt. ‘I may sleep badly’, I admitted, ‘but I love you. I walk up and down the embankments all night. My heart aches, my brain is on fire. Then comes blissful intoxication, and for a little while I can be happy. And all you can do is to keep nagging, Gertrude.’

She wrinkled her brow, but I went on impatiently, ‘Look, Rose dear, just at present I have the whole world throbbing in my temples and in my finger-tips. Age-old poems are bubbling up within me. I am grieving for lost youth. I am boggling at the future. For just this one moment it is given to me to see life with the living eyes of a real human being. Why won’t you let me be happy?’

‘I have walked two hundred kilometres’, said a low, timid voice at my elbow. I stopped. Yvonne had stuck her arm through mine. She, too, stopped. We both looked down and saw a little man. He doffed a ragged cap and bowed. Flushed scars glowed through a grey stubble of beard. He was wearing a much-patched battle-dress from which the badges had long since disappeared. His face was wrinkled, but the little eyes were animated and sorrowful. More…

Sensitivity session

30 June 1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Ja pesäpuu itki (‘And the nesting-tree wept’). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Taito Suutarinen knew quite a bit about Freud. Where Mannerheim’s statue now stands, Taito felt that there ought instead to be an equestrian statue of Sigmund Freud. It would be like truth revealed.

Freud, urging on his trusty stallion Libido, would be clad from head to foot in sexual symbols – hat, trousers, shoes: one hand thrust deep into his pocket, the other grasping a walking-stick. The stick would point eloquently in the direction of the railway tracks, where the red trains slid into the arching womb of the station.

Taito had also attended a couple of seven-day sensitivity training courses, where people expressed their feelings openly, directly and spontaneously. By the end of the first course Taito was so direct and spontaneous that he couldn’t get on with anybody. By the end of the second he was so open that everyone was embarrassed. Every member of the group had cried at least once, except the group leader. Never before had Taito witnessed such power. He could not wait to found a group of his own. Taito’s group met in a basement room, where they reclined on mattresses to assist the liberation process. Everyone was free to have problems, quite openly. You were not regarded as ill: on the contrary, if you realized your problem you were more healthy than a person who still thought he mattered. Moreover, as Taito, fixing you with his piercing gaze, was always careful to emphasize, every problem was ultimately a sexual problem. Taito would spontaneously scratch his crotch as he spoke, making it clear that he himself had virtually no problems left. More…

A day in the life of a bookseller

12 August 2010 | Reviews

The bookseller Aapeli [Abel] Muttinen, a central figure in Joel Lehtonen’s ‘Putkinotko’ books, is one of those fictional characters for whom Finnish readers have cherished a particular affection, not least because of his keen enjoyment of the pleasures they themselves so regularly share when they escape to their lakeside cottages for the summer.

But although Aapeli Muttinen is Finnish through and through, he is not without counterparts in the literature of other nations. One of his close relatives is the laziest man in all literature, Goncharov’s Oblomov; others, perhaps more surprisingly, can be found in the works of Anatole France – booksellers like Blaizot and Paillot, both gentle dilettanti with a streak of individualism and a penchant for good living. Like them, Muttinen is tolerably well-read: at the beginning of the short story ‘A happy day’ we find him musing about Horace, and at least one of Horace’s odes must have appealed to him strongly: ‘Happiest is he who, like his sires of old, / Tills his own ground, and lives his life in peace, / Far from the tumult of the noisy world.’

More…

Kullervo: to be, or not?

10 September 2010 | Articles, Non-fiction

A young man is born a slave under stars that augur ill for him. He is maltreated and betrayed from birth. He cannot control his physical power, his aggression or his thirst for revenge and, finally, after fatal errors and deliberate acts of violence, his remaining desire is to die. What, in the end, did life hold for him?

The cruelly tragic story of Kullervo in the Kalevala was largely the creation of the national epic’s compiler, Elias Lönnrot (1802–1884), who put together a number of originally unconnected folk-epic fragments collected in disparate localities throughout the north and east of Finland. This process involved many stages and went on for decades. The first version was published in 1835; for a shorter version for schools in 1862 Lönnrot cut the most violent and erotic scenes – including those involving Kullervo and his sister in an incestuous encounter. More…

Six letters

31 March 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Tainaron (1985). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

The whirr of the wheel

Letter II

I awoke in the night to sounds of rattling and tinkling from my kitchen alcove. Tainaron, as you probably know, lies within a volcanic zone. The experts say that we have now entered a period in which a great upheaval can be expected, one so devastating that it may destroy the city entirely.

But what of that? You need not imagine that it makes any difference to the Tainaronians’ way of living. The tremors during the night are forgotten, and in the dazzle of the morning, as I take my customary short cut across the market square, the open fruit-baskets glow with their honeyed haze, and the pavement underfoot is eternal again.

And in the evening I gaze at the huge Wheel of Earth, set on its hill and backed by thundercloud, with circumference, poles and axis pricked out in thousands of starry lights. The Wheel of Earth, the Wheel of Fortune… Sometimes its turning holds me fascinated, and even in my sleep I seem to hear the wheel’s unceasing hum, the voice of Tainaron itself. More…

The strike

13 December 1980 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Täällä Pohjantähden alla (‘Here beneath the North Star’), chapter 3, volume II. Introduction by Juhani Niemi

With banners held aloft, the procession of strikers moved towards the Manor. It was known that the strikebreakers had arrived early and that the district constable was with them. Just before reaching the field the marchers struck up a song, and they went on singing after they had halted at the edge of the field. The men at work in the field went on with their tasks, casting occasional furtive glances at the strikers. Nearest to the road stood the Baron and the constable. Uolevi Yllö’s head was bandaged: someone had attacked him with a bicycle chain as he left the field at dusk the evening before. Arvo Töyry was in the field too, the landowners having agreed that those who had got their own harrowing and sowing done should lend the others a hand. Not all the men in the field were known to the strikers. The son of the district doctor was there they noticed, and the sons of several of the village gentry, as well as the men from the smallholdings. More…

Kullervo

31 March 1989 | Archives online, Drama, Fiction

An extract from the tragedy Kullervo (1864). Introduction by David Barrett

The plot of the Kullervo story as told in the Kalevala: Untamo defeats his brother Kalervo’s army, and Kalervo’s son Kullervo is born a slave. Untamo sells him as a young child to llmarinen whose wife, the Daughter of Pohjola, makes the boy a shepherd and bakes him a loaf with a stone inside it. Kullervo takes his revenge by sending home a flock of wild animals, instead of cattle, who tear her to pieces. He flees, and discovers that his parents and two sisters are alive on the borders of Lapland. He finds them, but one of his sisters is lost. Life in the family home is unhappy: Kullervo fails in all the tasks his father sets him. On his way home one day he finds a girl in the forest whom he abducts in his sledge and seduces. It turns out the girl is his lost sister, who drowns herself when she learns that Kullervo is her brother. Kullervo sets out to revenge himself on Untamo; he kills and destroys. When he returns home, he finds the house empty and deserted, goes into the forest and falls on his sword.

ACT II, Scene 3

Kalervo’s cottage by Kalalampi Lake. It is night-time. Kimmo, seated by a fire of woodchips, is mending nets. More…